A Toe in the Water, Or, Beware the Under-Toad: Assessing the Benefits and Pitfalls of TBL-Light

Wendy Ashall

Outline

The team-based learning (TBL) literature makes wide-reaching claims regarding the benefits of adopting this pedagogical approach: improved learning, increased levels of engagement and participation, decreased social loafing, are promised alongside the ease of its applicability and suitability across disciplines (Espey, 2017, 2018; Lehmann-Willenbrock, 2017; Michaelsen, 2004; Michaelsen & Sweet, 2008, 2011; Stein et al., 2015; Sweet and Michaelsen, 2012; Travis et al., 2016; and Wilson, 2014). While the approach has been used extensively in schools, colleges and universities, both in the UK and the USA, a mixed picture emerges regarding whether TBL leads to improved student satisfaction (Travis et al., 2016). Nor does the literature address in sufficient detail the practicalities involved, nor does it assess the usefulness of the various ICT options available, the suitability of TBL for foundation year teaching, or its appropriateness for HE students with learning needs, disabilities or mental health issues such as anxiety. The TBL literature presents a somewhat rosy picture, stressing the benefits without going into much detail regarding any pitfalls encountered in implementing what, for some, may be a radically different approach to learning and teaching within higher education (HE).

The aim of this chapter is not to address the need identified by Travis et al. (2016) for more rigorous and scientific studies to produce evidence of the benefits of TBL, nor to provide a detailed review of the TBL literature as this is provided elsewhere (see, for example, Espey, 2017, 2018; Stein et al., 2015), but rather to provide a concise but honest ‘how to’ guide for practitioners interested in trialling TBL combined with Poll Everywhere, and an exploration of how we might assess its suitability for foundation teaching, based on the data a practitioner will have to hand. With these aims in mind, I briefly summarise the process and principles involved in TBL, drawing on a limited section of the literature. Next, I provide an overview of the context within which I trialled TBL and the rationale for the approach taken, before proving an account of what worked well and what worked less well, and how we overcame problems encountered along the way. I finish by including my early thoughts on the difficulties involved in assessing the usefulness of TBL for social science foundation teaching, but also some of my concerns which are not covered in the literature.

What is Team-Based Learning?

Team approaches to learning and teaching have a long history, with some identifying direct descent from the work of John Dewey (1922) due to his focus on cooperation, with productivity resulting from dependence (Betta, 2015: 69). More recent approaches can trace their origins to the Johns Hopkins Team Learning Project, at John Hopkins University (Slavin, 1978), and the later influential work of Larry Michaelsen and Michael Sweet (Michaelsen, 2004; Michaelsen & Sweet, 2008, 2011; Sweet & Michaelsen, 2012).

Team-based learning (TBL) is a highly-structured method of teaching and learning, in which learners are divided into the same small groups for the entire period of instruction and work together to deepen their understanding of the taught material by applying it to specially designed problem-solving activities (see Travis et al., 2016). Team approaches were initially used to teach basic skills (Slavin, 1978) but TBL has more recently been used to teach a wide range of topics across the disciplines, including (but not limited to) business studies, introductory psychology, medicine, criminology and the social sciences and humanities (Betta, 2015; Espey, 2018; Stein et al., 2015; Travis et al, 2016; and Wilson, 2014). TBL differs from other peer-focussed, active learning approaches in that it is more structured, but it shares features with the peer-led, evidence-based framework championed by Geoff Petty (2006) and John Hattie (2009), see Michaelsen and Sweet (2011). Most proponents of team-based learning (TBL) agree that five principles and processes are essential:

Stable Teams: Firstly, the teams should remain consistent across the semester (Travis et al., 2016). This is to enable trust and understanding to develop, such that the ‘groups’ are transformed into ‘teams’ over time (Lehmann-Willenbrock, 2017) as students come to trust each other and learn to negotiate to overcome differences (Espey, 2017).

Pre-Class Preparation: Secondly, students are required to complete pre-class preparation independently. This could include completing set readings, watching a video, or completing other preparatory activities. This reliance on individual pre-class preparation is shared with other ‘flipped’ approaches (Jakobsen and Knetemann, 2017) but is also consistent with the independent learning associated with HE.

In-Class Testing: Next, students first complete in-class quizzes, sometimes referred to as i-RAP or i-RAT (individual readiness assessment process or individual readiness assessment test). These are usually multiple-choice quizzes. The students then re-take the quiz, but this time in their teams. This stage is often referred to as the t-RAP or t-RAT (or team readiness assessment process or test). The results of the i-RAP/ i-RAT provide students with a grade-based incentive to complete the pre-class preparation (Stein et al., 2015: 30), but the t-RAP/ t-RAT provide a social incentive: students who do not prepare adequately (those who do not complete the pre-class preparation) will not perform well in the i-RAT. Their performance will also impact negatively on their teams’ performance in the t-RAT, thus promoting student-student accountability. Thus, TBL uses the desire to be accepted in the group as a motivation to learn (Stein et al., 2015). In this stage, students discuss the questions aiming to reach a consensus as to the correct answer. This has the benefit of encouraging students to both learn from and teach each other, in common with other peer-led approaches the students benefit from explaining their ideas to others, but also from having concepts explained to them in ways that differ from those used by their teachers (Stein et al., 2015: 28).

Application: In the next stage, the remaining class time is dedicated to application exercises designed to stimulate in-depth analysis, discussion and critical thinking (Travis et al., 2016). By providing the common goal of shared problems to solve, further incentivises cooperation (Stein et al., 2015) and this discussion is central to the success claimed of TBL, in that such discussion forces students to confront alternate points of view and the provision of peer feedback removes the need for additional tutor feedback (Espey, 2018).

Peer Evaluations: Finally, students are asked to grade the performance and contributions of their team-mates. The graded peer evaluations are used to ‘differentiate grades across team members, based on the varied contributions of each student’ (Stein et al., 2015: 28), which further incentivises each student to come to class fully prepared and rewards leadership (Stein et al., 2015: 31). TBL seeks to harness students desire to belong (Stein et al., 2015: 30), but also includes social sanctions against ‘free-riding’ via the desire to avoid social rejection and poor grades via the peer evaluation (Stein et al., 2015: 30). To do this, however, TBL requires the formation of stable groups (Stein et al., 2015: 30).

A wide range of benefits are claimed for TBL, including improved learning outcomes (Travis et al., 2016); increased levels of student engagement and participation (Stein et al., 2015; Wilson, 2014); the ability to learn and practice those skills required for employability, such as leadership (Betta, 2015); improved critical thinking skills (Espey, 2018); decreased ‘social loafing’ due to its active promotion of student accountability (Stein et al., 2015: 30); and improved group working skills, but also the development of student independence (Betta, 2015) whilst also overcoming the negative aspects of other group work approaches, such as personality clashes (Espey, 2017: 8). Despite the consistently positive assessment of TBL, its suitability has not yet been assessed for foundation teaching, or for those students with learning needs or those with disabilities or mental health issues such as anxiety. A mixed picture also emerges regarding whether TBL leads to improved student satisfaction (Travis et al., 2016).

What I did

Having reviewed the benefits claimed for TBL, I next provide an overview of the context within which I trialled TBL and the rationale for the approach taken. The module I convene is a core module on a social science foundation year course at a plate glass university. While foundation courses have a long history within the arts and medicine, in recent years they are increasingly offered as the ‘year zero’ of a four-year degree (UCAS, 2017). Foundation Year courses are now offered by 140 HEIs in England and Wales (UCAS, 2017). This course was established in 2015 and is now in its fourth year. Currently (2018/19) 208 students are enrolled. Students on the course take two core subject modules (one of which is my module) which span the social sciences, along with an additional academic skills module and an elective (one of the core modules from another foundation course: business, psychology or humanities). If students pass all four modules, they are guaranteed progression to a selection of degree options.

Most of our foundation students have recently completed their A-Levels but did not meet the entry criteria to progress directly into undergraduate studies. In line with the sector, small but increasing numbers of our students have either diagnosed or undiagnosed learning needs, such as dyspraxia, dyslexia, ADHD and ASD (Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, 2017: 11), and a sizeable proportion report anxiety and other mental health concerns (see McIntosh and Shaw 2017; Neves and Hillman, 2017: 45-7; Unihealth, 2018). The course aims to support all of our students as they transition into HE, via the provision of the academic skills module, more contact hours (in comparison with our undergraduates) and additional pastoral support as for some this may be a critical period (see Gale and Parker, 2014): this transition might prove especially challenging for those who ‘failed’ to meet their entry grades and might, therefore, have a less well-developed sense of themselves as successful students (see Field and Morgan-Klein, 2010, 2012) or those whose previous educational experiences might not have adequately prepared them for independent study (VandeSteeg 2012). The year-long module I convene introduces students to the methods and theoretical perspectives of the four disciplines that constitute the wider academic school: anthropology, international relations, geography and international development. This year (2018/19), 266 foundation students are taking the module, either as a core or as an elective: the students possess varied degrees of knowledge of, or interest in, the subject area.

In designing the module, I utilise a standard HE teaching modality: a one-hour lecture, delivered by researchers from across the school, followed by a two-hour seminar and accompanied by essential readings. By developing this format, I aim to prepare the students for the learning and teaching they will encounter once they progress to undergraduate studies, but also make use of the longer seminar time to create a supportive learning environment, in which learners can explore their identity as a university student and develop the sense of belonging associated with retention (McIntosh and Shaw 2017: 15; Thomas, 2012: 6-7) as well as benefit from the ‘sensitive scaffolding’ which make HE expectations explicit (Ridley, 2004 but see also Gale and Parker, 2014: 745). Teaching is delivered in fifteen seminar groups, each with between 20-22 students, by a three-person teaching team. I deliver three of the seminars, with the other twelve divided equally between two full-time Teaching Fellows. While I remain in place, to date the team has changed annually, with those employed having a range of teaching experience and qualification level. Seminars are designed using a student-led, active learning approach: we make extensive use of small group and peer-teaching activities to establish ‘communities of practice’ (Wenger, 2000) but also encourage students to draw on their prior experiences to build bridges between what they do and do not (yet) know (Ridley, 2004). The assessment modes used similarly aim to render HE expectations explicit: for example, in the autumn term students are required to complete a Reading Record in which they summarise, synthesise and evaluate the sets readings. This assessment aims to help them develop the habit of weekly reading, but also to develop those skills needed to prepare literature reviews.

In 2017 I commenced my doctoral research into the experiences of students on this course. Part of my motivation to do so was to rectify the lack of evidence regarding the ‘value and utility’ of foundation courses (UCAS, 2017). This four-year longitudinal multi-strategy case study follows the 2017/18 Social Sciences Foundation Year cohort until they complete their undergraduate studies. The discussion at the focus group (conducted in the spring of 2018) worried me: despite the extensive use of small group, peer-led teaching strategies, several participants stated that they had found it hard to make friends on the course. This was also an emergent theme in several of the one-to-one in-depth interviews I subsequently conducted with 21 of the cohort. It seemed that while students worked together well in the seminars, these relationships were not necessarily developing into friendships. I needed to find an alternative approach which would enable students to develop the deeper social networks associated with retention (McIntosh and Shaw 2017; Thomas, 2012), and that could be delivered consistently across the seminar groups by a potentially inexperienced teaching team. TBLs promise to turn ‘groups’ into ‘teams’, along with its promised benefits for student outcomes even when delivered by inexperienced teaching teams (Travis et al., 2016), appeared a viable solution.

The Process: How I Set Up TBL Using Poll Everywhere

I decided to trial TBL towards the end of the academic 2017/18 year. At that stage, I was uncertain whether my current teaching team would be continuing, and I had no information regarding the profile of the new students. Supporting these new students to develop those social networks positively associated with retention was the main reason why I was keen to try TBL, rather than any promised improvements in learning, not least because those improvements claimed are often quite small (see Travis et al., 2016: 104). A secondary aim was the promised improvements in engagement. While seminar attendance and submission rates were good, we found the amount of reading completed by the students varied considerably. I wondered if using the TBL readiness assessment tests would encourage more students to complete the readings, and also allow tutors to identify and support those students who were struggling with that week’s material.

Having decided that I wanted to trial TBL, the next thing was to decide how to do so. Given the lack of evidence regarding the suitability of this strategy for this specific cohort, and the mixed results regarding its impact on student satisfaction (Travis et al., 2016), I was not willing to adopt the approach wholesale not least as attendance, rates of achievement and student feedback were good. Furthermore, re-writing the year-long module would entail a considerable amount of work and potentially involve my preparing extensive resources that I would not use again if the trial proved unsuccessful. The approach I subsequently devised might be best termed ‘TBL-light’, in that I sought to integrate aspects of TBL into the existing curriculum design.

I decided to dedicate the first thirty minutes of each session in the autumn semester to the individual and group tests, using Poll Everywhere. Poll Everywhere was selected as we were already successfully using this technology to stimulate discussions in lectures, and students were comfortable using the application. Another benefit was that we would not need to purchase the scratch cards sometimes used and that Poll Everywhere has already been used for TBL (see Sibley, 2018). For the remaining seminar time, we would continue to use the jigsaw, peer led teaching, and discussion activities that we previously used, thus emulating the application stage of TBL. By reusing pre-existing resources, we could dip a toe in the water of TBL without committing ourselves (or our students and their outcomes) completely. If the approach were successful, we would decide later whether to expand the trial.

After a great deal of consideration, I decided not to include the peer evaluation aspects of TBL. Cestone et al. (2008: 70) state that these peer evaluations provide the formative information needed to help individual students improve team performance over time and develop the interpersonal and team skills essential for their future success. They also find that peer evaluation scores provide summative data to the instructor that can be used to ensure fairness in grading. By incorporating an assessment of each member’s contributions to the success of their teams and make judgments about it, students become assessors; they are required to show a more thoughtful understanding of the processes involved leading to both increased confidence and increased quality of the learning output (Cestone et al. 2008: 70). I had previously tried to use peer feedback on assessment planes with a previous year’s cohort and found it caused anxiety for many students. While admittedly this was when the cohort had been much smaller, I was reluctant to risk including this aspect of TBL even though this impression was not supported with substantial evidence. I reasoned that this could be integrated in a subsequent year, once the suitability of this approach for this cohort was more firmly established.

The first task was to write the questions for the individual and team quizzes. Writing the questions was incredibly time consuming and difficult. As a teacher, I am well-used to using questioning to test and push student understanding but I rarely script these, and I initially found the multiple-choice format challenging, and I am not used to preparing questions that require a ‘correct’ answer. On reflection, many of the resulting questions were quite basic, closed type questions. However, I was hopeful that the questions could be further improved for subsequent use. The next task was to embed the quizzes into the sessions plans, which necessitated some reflection on previous deliveries to identify which of the activities would be retained and which should be removed. Setting up the multiple-choice quizzes in Poll Everywhere was very straightforward, as was sharing these with the new team once they were in post. The team went through how to use the Poll Everywhere application, and we completed a couple of dummy-runs which were useful in clarifying the aims and process involved.

One problem that quickly emerged concerned that of keeping the students in the same groups throughout the semester. The composition of the groups has been examined by Espey (2017) who state that faculty should be more careful when designing teams to ensure members have complimentary skills. However, we had very little information about the students beforehand, and the initial allocation of teams was therefore random. Some students were not happy with their initial team allocation and contacted members of the teaching team, asking to be moved to another group: this was either due to their frustration that team members were not coming adequately prepared or due to having team members with poor attendance. Michaelsen and Sweet (2008) identify three specific areas which develop student peer accountability in TBL: (1) individual pre-class preparation, in that students are more likely to complete pre-class preparation and perform better in the tests. Subsequently, students who come to class less well prepared are (2) better able to contribute positively to their team’s performance. Students reward each other in the peer evaluation. Knowing that that are being evaluated by their peers provides further motivation to contribute. Such (3) high-quality team performance should be evident in peer evaluations. However, I had chosen not to include the peer evaluation stage due to the concerns I outlined above. It might be that this decision removed an important stimulus of peer accountability. Nonetheless, as ‘faculty should be attuned to divisions or conflicts on teams and attempt to alleviate such problems to the extent possible, as well as encouraging contributions from all students with in teams’ (Espey, 2017: 19) we let students switch from their initial teams. For some seminar groups, attendance was an issue: with all group members rarely fully present, we quickly found it necessary to change the groups each week, but this made it difficult to compare the performance of the groups or to measure the progress of each group week on week.

Another issue we encountered concerned feedback. As outlined above, a key feature of TBL is that students benefit from immediate feedback on their individual test answers (see Michaelsen & Sweet, 2011: 42). Often this is achieved via the use of Immediate Feedback Assessment answer sheets (IF-AT) in the form of scratch cards (Michaelsen & Sweet, 2011); as the students re-take the tests in groups, they can quickly see which answers they got correct on their first attempt. Poll Everywhere enabled us to identify the students (once fully registered) so that we could offer more support to students who had struggled in the rest of the class, but we could not share their answers with them without also sharing the scores of other students. To help with this, we went through the correct answers as a group, discussing the reasons why potential answers were either correct or incorrect. We found that these discussions proved to be useful spaces in which to provide more detailed clarification regarding subject content. The quiz questions and answers were then shared weekly on the VLE site.

Assessing TBL: Suitability and Outcomes

It was not possible at this stage to conduct a substantial assessment (such as primary research) into whether TBL did positively contribute to students developing those friendships associated with retention (McIntosh and Shaw 2017; Thomas, 2012). As part of the small-scale, ‘toe in the water’ type approach outlined above, our decision as to whether TBL was an approach we wished to continue with was based on a range of readily at hand information: a comparison of seminar attendance, submission rates and grades along with the results of a midterm feedback surveys collected for the past three years (I only have access to data for those years when I served as module convenor; 2016/17 onwards). While it is right to acknowledge that it would be preferable to base pedagogic decisions on firmer evidence, I suspect that too often similar judgements are made on still shakier foundations, and I hoped the findings might provide some basis on which to decide the direction of travel.

Attendance

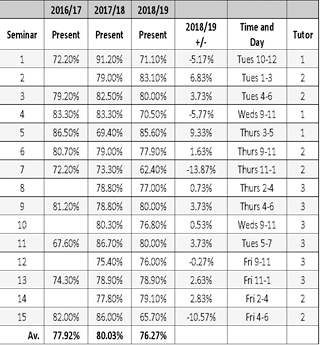

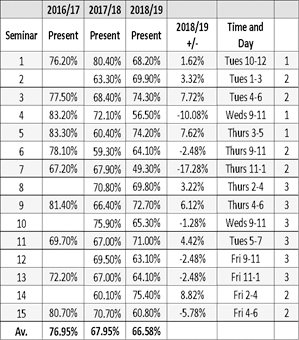

Student attendance rates were also taken as a proxy measure of student engagement as students who are motivated to complete preparatory work are more likely to be those students who attend seminars, and, hopefully, also benefit from improved opportunities to make friends. A register is taken at all seminars, however the way that this data was recorded varied year on year: 2016/17, 2017/18 and 2018/19 the cumulative percentage was recorded midway through the autumn semester, in week 6 (fig. 1); in 2018/19 attendance was also recorded in week 12 (fig. 2).

Comparing attendance rates by seminar group across the three years (fig.1) was problematic, as each was delivered by a different member of staff in a different teaching slot (time and day) so the teaching slot and tutor identified for analysis from Fig. 1 are for 2018/19 only. When looking solely at attendance in 2018/19, of the five groups with attendance below the mean average, two were delivered by me (groups 1 and 4) another two were delivered by the least experienced tutor (groups 7 and 15) and the final group but the most experienced tutor (group 12). Four of the groups with the lowest rates of attendance were in the morning, but one group was scheduled on Friday afternoons (fig.1).

Somewhat worryingly, in the second half of the term, attendance continued to decline as the semester progressed, so that by the end of the autumn semester the mean average attendance was 66.58% (fig. 2): this is unusually low. Again, there appears to be no clear pattern, in that the groups with poor attendance were delivered by all three members of the teaching team and were scheduled on different days, and all (except for group 15) were delivered in the mornings.

I do wonder whether TBL itself had a negative impact on attendance: whereas in previous years students who had not completed the preparatory reading might attend the seminar anyway, perhaps the formally assessed aspect of TBL meant that they were less likely to attend? Another issue that might be a factor is student anxiety: there have been widespread reports of alarming increases in rates of anxiety in young people, challenging universities nationally. Might it be the case that TBL might exacerbate student anxiety? Stein et al. (2015) found that student shyness proved a barrier to participation for some students, which their team mates were willing to accommodate to some degree.

Submission Rates and Grades Achieved

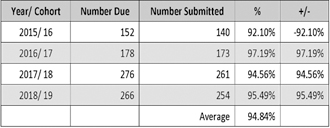

I next compared submission rates and grades achieved for the Reading Record with those for the previous three years, as this was the assessment mode for the period in which we trialled TBL (the autumn semester). This is not an ideal measure, but by making this comparison I hoped to assess whether TBL had had a positive impact on student engagement with the module contents using the data available to me: if effective, TBL would motivate students to complete the preparatory tasks as well as enable tutors to more effectively identify which students would benefit from in class support. I hoped that students who have completed the reading and benefited from support targeted to those weeks or topics where they most struggled, would be better placed to submit the first assessment.

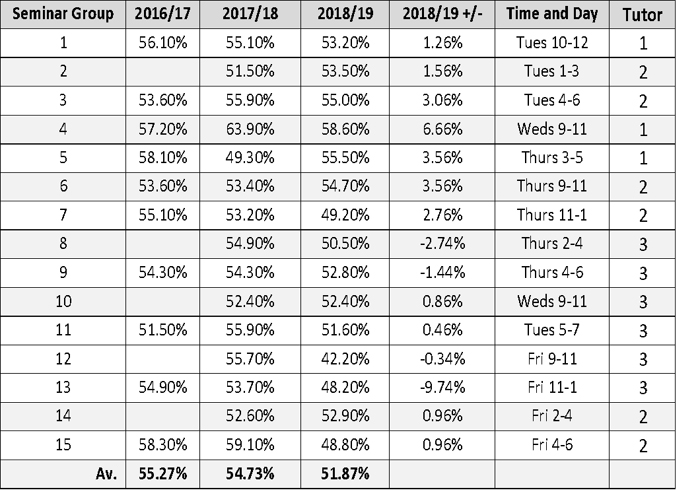

However, a quick look at submission rates (fig. 3) indicated no clear impact: submission rates peaked in 2016/ 17, and although submission rates were marginally different in 2018/19 in comparison with 2017/18, the numbers involved are small. Similarly, I had hoped that comparing grades achieved by the seminar groups would help me to assess whether TBL was delivered consistently across seminars (fig.4), though one must be careful not to imply simple causation between teacher expertise and student outcomes as so many other factors are involved.

When looking solely at work submitted 2018/19, those four groups with mean average grades below the average for 2018/19 (groups 8, 9, 12 and 13) all had seminars delivered by seminar tutor 3, an experienced tutor (fig.4). However, no conclusions can be reached as groups 8 and 9 were marked by the tutor who delivered the seminars whereas groups 12 and 13 were marked by someone outside of the teaching team. Comparing the mean average grade, however, revealed that these have decreased since 2016/17, though the rate of decrease is small (fig.4). If TBL had negatively impacted on attendance, the result might well be this decrease in mean average grades.

There also seemed to be no clear pattern regarding how grades were distributed: for example, the group with the lowest mean average grade (group 7) at 49.30% attendance in week 12 (fig. 3) also achieved a low mean average grade of 49.20 (fig. 4), but the lowest mean average grades were achieved by group 13 at 48.20 (fig. 4), even though this group had attended relatively well at 64.10% (fig.2). The group with the highest mean average grade, group 4 (fig. 4), had the second lowest rate of attendance (fig. 2).

Student Feedback

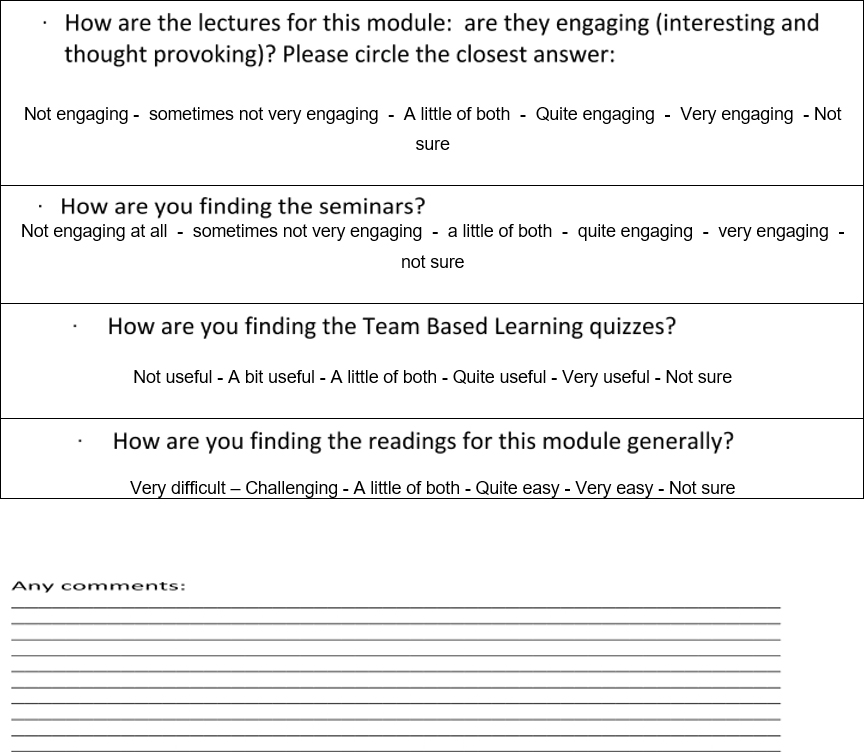

With no clear picture emerging regarding the impact of the TBL trial I turned to student feedback. Student feedback was collected via a paper survey midway through the autumn teaching term (week 5) just before reading week (appendix one). The one exception was seminar group 7, where low attendance in week 5 meant that the survey was not completed until week 7. When collecting data, we need to make two decisions: what to measure and how to measure it (Field, 2009: 7). This survey is routinely delivered at this point, as part of the quality control measure, to assess student perception of the usefulness of the three modes of delivery used on the course: lectures, reading and seminars. A further question was added to determine student perception of TBL. Thus, the survey sought to capture a snapshot of student’s perceptions midway through the block of TBL teaching (Field, 2009: 12) for quality control purposes. The surveys were distributed and completed at the end of seminars, with the seminar tutor nominating one student to collect the completed sheets, placing them in a plain envelope and delivering them to the course administrative office. In this way, it was hoped that the students would feel free to record their honest responses.

There are several limitations associated with the approach taken here. As the survey was completed in seminars, students with poor attendance were less likely to be included; this has implications as students may not attend due to negative feelings towards the course and the teaching methods (including TBL), skewing the data toward positive perceptions.

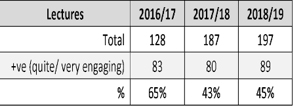

Of the students who complete the survey and completed this question, the percentage who positively assessed the lectures for the degree of engagement varied but declining assessments did not coincide with the TBL trial (fig.5).

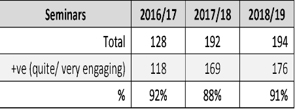

The percentage of students surveyed who positively assessed the seminars dropped in 2017/18 but returned to previously levels in 2018/19 (fig.6). Trialling TBL did not appear to have had a negative impact on the student’s assessment of seminars.

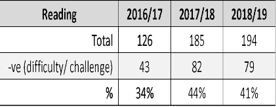

Slightly fewer students found the reading to be challenging 2018/19 than previously, which could be attributed to students benefiting from improved peer support but could just as well reflect the different readings assigned by lecturers (fig.7).

Figure 8: Positive Assessment (Usefulness) of TBL

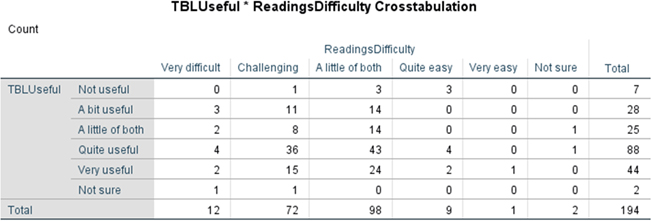

The majority of surveyed students found TBL to be useful (fig. 9), combined with the lack of negative impact on student assessment of seminars indicates a positive assessment of TBL.

I had wondered if there would be a relationship of some sort between the student’s assessment of the difficulty of the reading and the usefulness of TB (fig. 9). Would it be the case that those who found the readings most difficult most appreciate TBL and vice versa? The evidence was unclear: those students who found the reading to be difficult also found TBL to be useful. However, those few students who found the texts less challenging varied in their assessment of the usefulness of TBL.

Conclusion

A quick review of the TBL literature reveals the broad ranging claims made for this approach: improved learning outcomes; increased levels of student engagement and participation; improved critical thinking skills; and improved group working skills. Despite the consistently positive assessment of TBL across its suitability has not yet been assessed for foundation teaching, or for those students with learning needs or those with disabilities or mental health issues such as anxiety. A mixed picture also emerges regarding whether TBL leads to improved student satisfaction (Travis et al., 2016). However, initial finding from my doctoral research into the experiences of students on a foundation year module indicated that some students were finding it difficult to develop those relationships with peers that are associated with retention. In looking for an alternative teaching strategy, TBL appealed due to the claims made regarding its ability to turn ‘groups’ into ‘teams’ (Travis et al., 2016). Having decided that I wanted to trial TBL, but with concerns that its suitability for this cohort was not yet established, the approach I subsequently devised might be best termed ‘TBL-light’ in that I sought to integrate aspects of TBL into the existing curriculum design. We would use the testing stage (individual and team) delivered via Poll Everywhere but that we would not use the peer evaluations at this stage, due to concerns regarding student anxiety.

Using the data that I had access to, it was difficult to assess either the effectiveness or the suitability of TBL for this cohort and the picture that emerged was contradictory and incomplete. The attendance data appeared to indicate that TBL was having a negative impact, as the mean average attendance was unusually low (66.58%), though caution here is wise given the lack of comparable data across the years. Could students (especially those who are anxious regarding their seminar performance) find the thought of being responsible for others performance too much to bear? Stein et al. (2015) found that student shyness proved a barrier to participation for some students, but also that their team mates were willing to accommodate shyness, but that assumes that students were able to be present. Examining rates of assignment submission and grades achieved was unhelpful: although there was a marginal difference in submission rates in 2018/19 in comparison with 2017/18, the numbers involved were small. There was also no clear pattern regarding the grades achieved, though worryingly the mean average grades were slightly down on previous years. Student feedback indicated that the majority (69%) found TBL to be useful, and there was no negative impact on their evaluation of the seminars. On the other hand, introducing elements of TBL did not help halt the declining appreciation of the lectures.

It might be the case the low attendance in some seminars, combined with individuals moving teams, undermined the development of the interpersonal trust and mutual respect which contributes to the development of effective teams (Espey, 2017: 19), but the data that I had access to was not sufficient to fully assess the suitability of TBL for this cohort, leaving me unsure whether we should continue with the trial, especially given the negative impact identified on attendance and grades. Returning to the TBL literature, I found little discussion regarding what to do if TBL is less than effective or the delivery goes awry in any way. Indeed, there is little evidence of critical engagement with the approach. Lane (2008: 56) serves as a case in point: when discussing effective implementation, he is clear that this is dependent on the communication skills and techniques of the instructor:

“For optimal results using TBL, instructors should be knowledgeable, flexible, spontaneous, and confident with the team-based learning process. They need not be flawless with the process, but there are some important instructor characteristics that are beneficial to the successful implementation of team-based learning” (Lane, 2008: 66).

He also warns of the dangers of partial adoption: TBL must be adopted completely, or ‘instructors’ risk negative experiences for their students (Lane, 2008: 55). Given the concerns outlined above, a complete adoption of TBL without clear evidence of its benefits appears riskier still and locating any failings in the delivery of TBL with the personality of the ‘instructor’ is less than helpful. It would be more useful if other authors share more details regarding how and why they decided to adopt TBL, and on what evidence they based this decision.

As a team we have instead decided to again survey the students, specifically on their experience of seminars in the autumn semester as the evidence we have is not clear enough to guide our next steps. We are hoping that by doing so, we will gain a better understanding if the trial of TBL contributed to declining attendance and the slight drop in mean average grades. We will also compare the grades this year’s cohort achieved in the autumn semester with their grades in the spring and against those for previous years. We will also look closely at the level of challenge and degree of satisfaction data, collected centrally towards the end of the year, again comparing the results from this year with previous years, so try to see whether TBL has had any impact. In the meantime, we have identified what needs to be improved with our resources, if we do decide to trial TBL again next year: we need to revise and improve the quality of the questions used in the quiz; we need to find a way to provide immediate feedback to individual students, so that they can see for themselves how working as a team is beneficial. We also need to make the links between the quiz elements and the application activities much clearer, and we need to find a way to improve the stability of the teams as I suspect that I had underestimated how important this aspect of TBL is, probably as this is less important in the cooperative learning approaches with which I am more familiar (see Michaelsen and Sweet, 2011). In conclusion, team-based learning may have its advocates, but I remain, at this stage and without clearer evidence, somewhat sceptical regarding the claims made.

Appendix One: Mid-term student feedback survey questions

Global Issues Local Lives:

Module Feedback

References

Betta, Michela (2015) ‘Self and Others in Team-Based Learning: Acquiring Teamwork Skills for Business,’ Journal of Education for Business Vol. 91, pp. 69–74.

Cestone, Christina M; Levine, Ruth and Lane, Derek R. (2008) ‘Peer Assessment and Evaluation in Team-Based Learning’ New Directions for Teaching and Learning, No. 116, pp. 69–78.

Dewey, John (1922) Human Nature and Conduct: An Introduction to Social Psychology, New York, NY: The Modern Library.

Espey, Molly (2018) ‘Enhancing Critical Thinking Using Team-Based Learning,’ Higher Education Research and Development Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 15–29.

Espey, Molly (2017) ‘Diversity, Effort, and Cooperation in Team-Based Learning,’ The Journal of Economic Education Vol. 49, pp. 8–21.

Field, Andy P. (2009) Discovering Statistics Using SPSS: And Sex, Drugs and Rock “N” Roll (3rd Ed.) Los Angeles: SAGE Publications.

Field, John, and Natalie Morgan-Klein, Natalie (2010) ‘Studenthood and Identification: Higher Education as a Liminal Transitional Space,’ in 40th Annual SCUTREA Conference. Education-line/British Education Index, online at <?APEXHYPERLINK ?> http://dspace.stir.ac.uk/handle/1893/3221, accessed 08.09.2017.

Field, John; and Morgan-Klein, Natalie (2012) ‘The Importance of Social Support Structures for Retention and success’ in Hinton-Smith, Tamsin (2012) Widening Participation in Higher Education: Casting the Net Wide? Issues in Higher Education. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 178-193.

Gale, Trevor, and Stephen Parker (2014) ‘Navigating Change: A Typology of Student Transition in Higher Education,’ Studies in Higher Education Vol. 39, No. 5, pp. 734–53.

Hattie, John (2015) ‘The Applicability of Visible Learning to Higher Education,’ Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology 1, No. 1, pp. 79–91.

Hattie, John (2009) Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement, London: Routledge.

Jakobsen, Krisztina and Knetemann, Megan (2017) ‘Putting Structure to Flipped Classrooms Using Team-Based Learning’, International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education Vol. 29, No. 1, pp. 177–85.

Lane, Derek R. (2008) ‘Teaching Skills for Facilitating Team-Based Learning’, New Directions for Teaching and Learning, No. 116, pp. 55–68.

Lehmann-Willenbrock, Nale (2017) ‘Team Learning: New Insights Through a Temporal Lens’, Small Group Research Vol. 48, No. 2, pp. 123–130.

McIntosh, Emily and Shaw, Jenny (2017) ‘Student Resilience: Exploring the Positive Case for Resilience’, Unite Students, <?APEXHYPERLINK ?> http://www.unite-group.co.uk/sites/default/files/2017-05/student-resilience.pdf, accessed 05.06.2017.

Michaelsen, Larry K. (2004) ‘Getting Started with Team-based Learning’, in Team-based

Learning: A Transformative Use of Small Groups in College Teaching, Michaelsen, Knight and Fink (Eds.), Sterling, VA: Stylus, pp. 27–50.

Michaelsen, Larry K., and Michael Sweet (2011) ‘Team-Based Learning,’ New Directions for Teaching and Learning Vol. 128, pp. 41–51.

Michaelsen, Larry K., and Michael Sweet (2008) ‘The Essential Elements of Team-based Learning’, Team-based Learning: Small-group Learning’s Next Big Step, Michaelsen, Sweet and Parmelee (Eds.), San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, pp. 7– 27.

Neves, Jonathan and Nick Hillman (2017) 2017 Student Academic Experience Survey: Final Report, Higher Education Academy and Higher Education Policy Institute, online at <?APEXHYPERLINK ?> https://www.hepi.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/2017-Student-Academic-Experience-Survey-Final-Report.pdf, accessed 11.02.2019.

Petty, Geoff (2006) Evidence Based Teaching, Gloucestershire: Nelson-Thornes.

Ridley, Diana (2004) ‘Puzzling Experiences in Higher Education: Critical Moments for Conversation’, Studies in Higher Education Vol. 29, No. 1, pp. 91–107.

Sibley, Jim (2018) ‘Technology That Can Help TBL,’ Learn TBL (blog) online at <?APEXHYPERLINK ?> https://learntbl.ca/technology-that-can-help-tbl/, accessed February 18, 2019.

Slavin, Robert E. (1978) ‘Using Student Team Learning,’ The Johns Hopkins Team Learning Project, John Hopkins University: Centre for Social Organisation of Schools.

Stein, Rachel E., Corey J. Colyer, and Jason Manning (2015) ‘Student Accountability in Team-Based Learning Classes,’ Teaching Sociology Vol. 44, pp. 28–38.

Sweet, Michael and Michaelsen, Larry K. (2012) Team Based Learning in the Social Sciences: Group Work That Works to Generate Critical Thinking and Engagement, Sweet and Michaelsen (Eds.), Virginia: Sterling.

Thomas Liz (2012) ‘Building Student Engagement and Belonging in Higher Education at a Time of Change: A Summary of Findings and Recommendations from the What Works? Student Retention & Success Programme’, Higher Education Academy, online at <?APEXHYPERLINK ?> https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/system/files/what_works_summary_report_1.pdf. accessed 02.03.2017.

Travis, Lisa L., Nathan W. Hudson, Genevieve M. Henricks-Lepp, Whitney S. Street, and Jennifer Weidenbenner (2016) ‘Team-Based Learning Improves Course Outcomes in Introductory Psychology,’ Teaching of Psychology Vol. 43, pp. 99–107.

UCAS (2017) ‘Progression Pathways 2017: Pathways through Higher Education’. <?APEXHYPERLINK ?> https://www.ucas.com/file/110596/download?token=aVG758ND, accessed 28.10.2017

Unihealth (2018) Upwardly Mobile: Can Phone Messaging Plug the Gap in Student Mental Health Support? online at <?APEXHYPERLINK ?> file:///C:/Users/wjash/Downloads/_images_uploads_unihealth_report.pdf accessed 11.02.2019.

Universities UK (2015) ‘Student Mental Wellbeing in Higher Education: Good Practice Guide’, London: Universities UK, accessed February 11th, 2019.

VandeSteeg, Bonnie (2012) ‘Learning and Unlearning from School to College to University: Issues for Students and Teachers’, Teaching Anthropology Vol. 2, No. 1, online at <?APEXHYPERLINK ?> http://www.teachinganthropology.org/index.php/teach_anth/article/view/329. accessed 01.12.2016.

Wenger, Etienne (2000) ‘Communities of Practice and Social Learning Systems,’ Organization Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 225–46.

Wilson, Michael L. (2014) ‘Team-Based Learning,’ American Journal of Clinical Pathology Vol. 142, p.4.