6 Messages and messengers

For each of our audiences, we now have a general idea about what to say, but how can research methods help understand more about how to say it?

Professor Sarah Dillon and Dr. Claire Craig explain in their book Storylistening how analysis of narratives can provide insights into public reasoning, and strengthen and complement scientific evidence. They argue that both scientific and narrative evidence should be incorporated into policy design and public engagement programmes. They propose a conceptual framework that we might apply to study existing stories and narratives in order to understand what audiences are already hearing, and use that knowledge to build more effective communication interventions.

You can read more on the Storylistening website [www.storylistening.co.uk].

Principles for framing what we say

The University of Florida’s Center for Public Interest Communication [https://realgoodcenter.jou.ufl.edu] conducts multidisciplinary literature reviews to understand more about how we can frame what we say to our audiences, and what makes certain interventions successful. They compiled five principles for more effective communication that we can think about using across all our messages, with all of our audiences.

Center for Public Interest Communications’ Five principles for effective communications

- Join the community. Identify a group whose change in behaviour could make a profound difference for your issue or inspire others to take action. Figure out how to bring that group value.

- Communicate in images. Use visual language instead of abstract concepts to help people connect with your work.

- Invoke emotion with intention. Think about what you’re trying to get people to do and how they would feel if they were doing it. Then think about stories that would make them feel that way.

- Create meaningful calls to action. Review your calls to action to make sure they ask communities to do something specific that will connect them to the cause and that they know how to do.

- Tell better stories. Go beyond simple sharing messages – tell interesting stories with a beginning, middle, and end.

These principles are important because they give us data-driven insight into how we can best interest and inspire our audiences by meeting them where they are, communicating visually, using emotions intentionally, giving audiences useful information where it’s necessary, and telling interesting stories. Many of us live in a messy information environment where we are inundated with messages every day. These principles can help us cut through the noise to ensure our messages will be interesting to our audiences, which will increase our visibility, and ultimately our impact.

Some other principles we’ve learned about developing effective messages include:

- Make the message memorable. For generations we’ve imparted knowledge by telling stories: think about the protagonist, a beginning, middle and end, a tension and resolution, in order to draw audiences in and maintain their attention.

- Make the message stick. We’ve also imparted knowledge by using proverbs and metaphors: designed well, these can be useful ways to build recognition and resonance with audiences through the messages you use.

- Make the message informative. Humans are thirsty for knowledge: can you tell a story in a way which explains something they don’t know, or adds value to their experience of the world?

- Play on emotions people WANT to feel. Instead of shaming them, or generating fear and eco-anxiety, how can we move people using awe, joy, or surprise? Outrage can be a useful emotion to move people to take action on a specific issue, but it can also turn people off: use outrage sparingly and use it with care. Of course, it’s complex — there is a lot of research looking at hope vs. fear in climate communication, and the results aren’t always clear cut — but playing on emotions people WANT to feel is a good rule of thumb to draw them into your message.

- Provide templates and examples for action. If audiences clearly see what they might do, they can sometimes come up with their own ways of feeling about it, and their own reasons for doing it (before, during, and after).

- It can be useful to connect to things your audience already cares about. This could take the form of partnerships or placement of your messages in locations where you expect them to be (digital or otherwise). It may also help you to think about ways to connect your issue to other issues to demonstrate adjacency, or to pique their interest. You may have to strike a balance though, and not allow this to draw you too far from your core messaging. More on this later, in ‘Identifying emergent opportunities’.

- Consider in advance what feelings and dialogues might emerge, and how you might respond. Communication is almost always best when it is not just one-way. Depending on the nature of your campaign, opportunities to interact with your audience might be plentiful (for example, at live events) or more limited (for example, if you receive a few comments on social media). Listening openly and honestly, and being prepared to deepen your understanding of the issues, should be your first priority. At the same time, it can be helpful to think about how people might feel about your message, and how you can turn negative or ambiguous responses into positive ones. In the context of climate change communication, Adam Corner writes, ‘People rarely feel just one emotion, and the simultaneous experience of different emotions may have unpredictable interactive effects, particularly with respect to promoting long-term, sustainable shifts in behavior. Instead of artificially trying to evoke a particular emotion, a better way might be to focus on the emotions that people already feel about climate change, to understand their motivations and reasons for feeling those emotions.’

Principles for choosing who should say it

In addition to how we talk to our audiences, we can also learn from research methods about who should talk to our audiences. These are often known as ‘messengers’. A messenger could be a protagonist in a story, or a voiceover that explains a concept, or even a celebrity who wants to help us get our message out. Some principles we’ve learned about selecting effective messengers includes:

- Messengers are as important as the message. Think about your target audience, what you want them to know and understand/do, and who would best encourage them to do that. Who would older audiences want to hear from? Who would younger audiences want to hear from? Align your messenger with your specific audience, and ideally ask individuals representative of your audience for their view. In the absence of a focus group with older audiences, simply asking older people you work with could provide useful insight.

- Don’t let inauthentic messengers take the space of authentic messengers with lived and/or generational or technical expertise. For many years, wealthy, white and Western voices have dominated public interest communication, as the majority of funding for many projects emerged from the whiter, wealthier West. This has meant that over the years, many messages have failed to resonate appropriately with important groups of people – or at worst, they have actively alienated their participation.

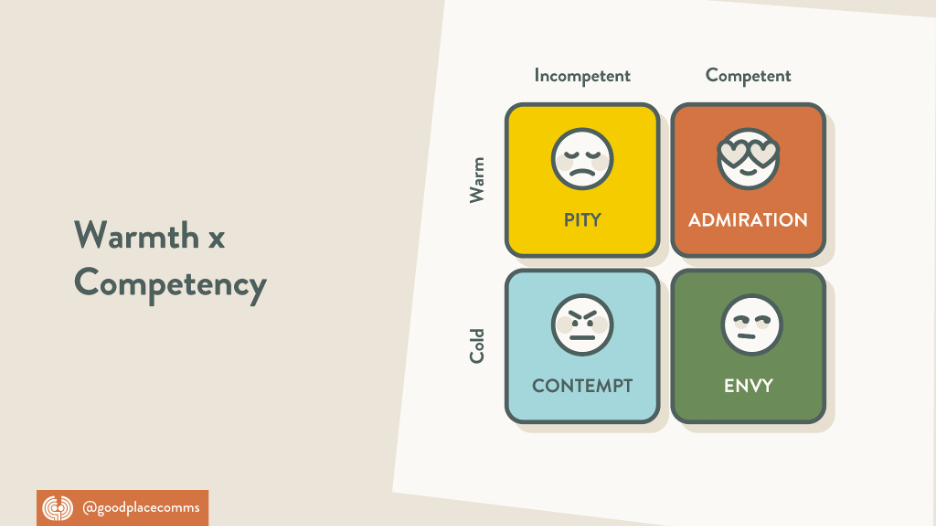

- Think about where messengers sit in terms of warmth and competence. A combination of warmth and competence has been found to be most effective in making audiences pay attention and respect the information given. Not every messenger will fit both, but can we pair our messengers to make sure they demonstrate to audiences that they are both warm (share universal human values and can be a trusted voice in this space) and competent (know their subject matter or are solutions-focused?)

- In the same way, some messengers are more effective at drawing attention to an issue (e.g. celebrities or politicians), while others are better at persuading people to care or take action (someone credible, with subject matter expertise or lived experience). Think about your intended outcomes and perhaps select messengers to do both.

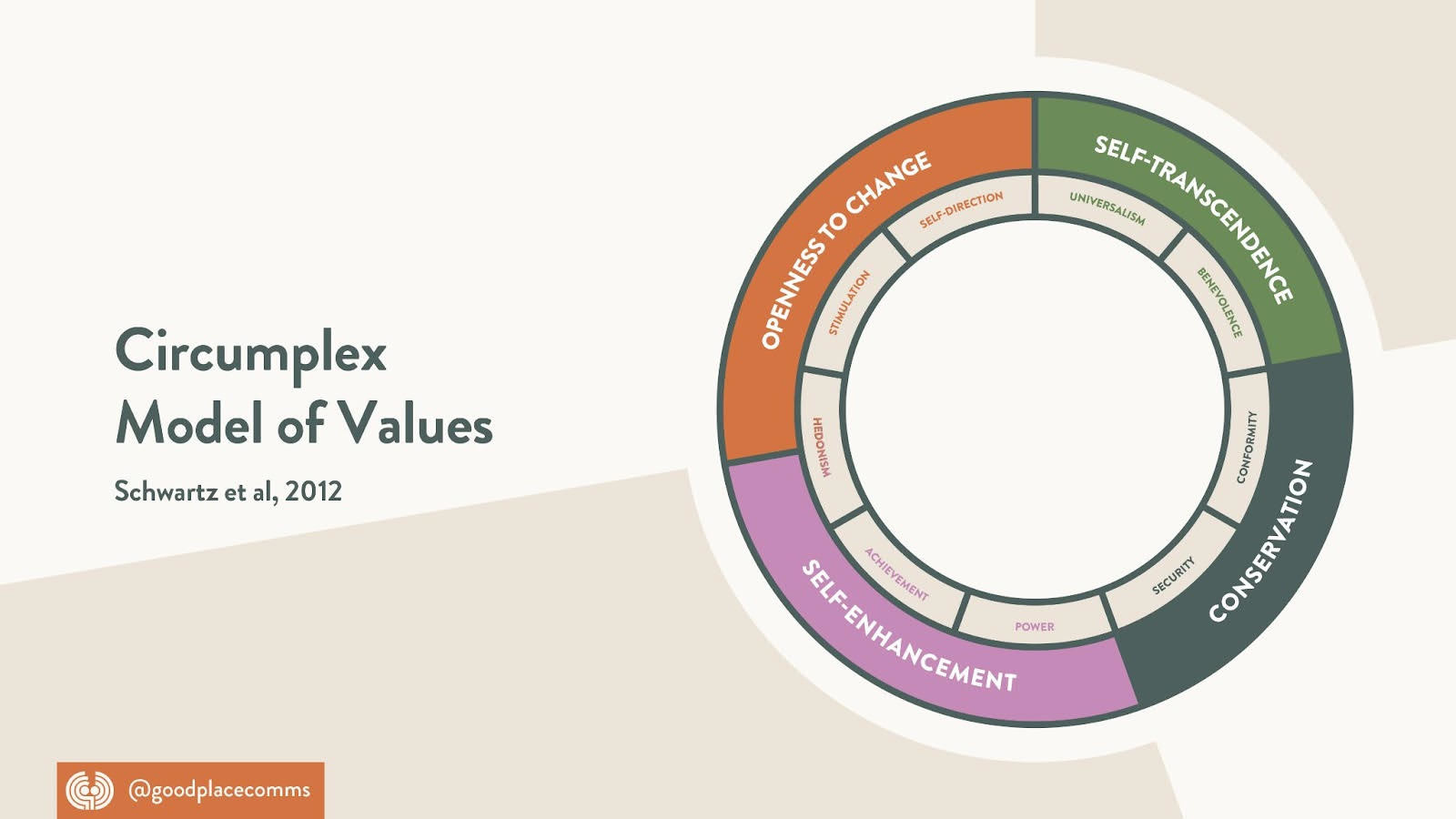

We talk a lot in public interest communication about our values, and those of our audiences, so it’s worth exploring in more detail here. Thanks to public opinion research, scientists have increasingly found that human values are a more significant predictor of perceptions and behaviour than traditional demographics, ‘social status’ and wealth. What can we understand about our audience’s values? What drives them in their daily lives, in how they think about the world, in what topics they’re interested in, who they listen to? Public opinion research can help us develop profiles of our audiences to help us think about the best ways to reach them, with our messages, our messengers, and our media targeting.

In a survey setting, most people in most countries report prioritising benevolence and justice values, while some people prioritise conformity and security, or protection from harm. They will perceive messages differently and may require different approaches in your messaging. Think about your various audiences and imagine what sorts of values you think they’d be most likely to prioritise, and apply these values to your messages and messengers.

One note of caution: in today’s often polarised world, we should use caution using values which might divide our audiences. To win the support of one group, while alienating another, may not be helpful to us. Attempts to use ‘coded language’ which speaks mostly to a particular political audience may be seen by all, and could cause your integrity to be doubted, and your issue to become unnecessarily controversial.

You might avoid unnecessary polarisation by applying common-sense principles to why something is important, or finding ethical values which speak to universal human nature as well as matter-of-fact logic to why we think a particular approach will be effective. However, it’s worth being aware that overtly moralising an issue – a common mistake made in public interest communication – can also backfire.

This is often due to where people sit on the stages of change model (see Understanding Audiences). If our audience already knows the moral argument, but doesn’t know how to act, reiterating only the moral argument can come across as condescending. Think about using moral language as part of the message, but not the whole message. What is the ‘so what’? We may want to save the planet because it’s the right thing to do, but also why? How will it also benefit the lives and livelihoods of our audiences and those around them?

Also keep in mind that appeals to universal human nature or experience can easily marginalise or silence those who don’t neatly fit the template — while amplifying the voices that are already loud and clear. Think about who you’re speaking to, as well as who you might NOT be speaking to (who you might have overlooked), and decide whether you need to make some changes.