12 Analysing the language used in the Tricontinental journal by revolutionaries to describe themselves, their enemies and an emancipated future

Jay Lynch

I’m a final year philosophy undergraduate at Sussex University, I’m also a pro-Palestine activist both on and off campus. My activism naturally led me to the Tricontinental archive as a source of great living history, a reminder of the dangers we face in our modern times – as well as a guide for our current activism in the face of an increasing threat from the far-right.

Tricontinental‘s unique coverage of global anti-imperialist struggles, as well as anti-imperialist movements within the imperial base in the United States, inevitably necessitated the use of a particular writing style. In sifting through the collection, an immediate aspect that stood out to me was the language used by revolutionary authors in the magazine used to describe themselves, their comrades and fellow revolutionaries in other movements – often appealing to the language of bravery and heroism (the language of the history of great men, as Nietzsche would say).

In contrast to this, the language used by these revolutionaries to describe their enemies, fascist governments, dictatorship, the United States, NATO and European powers is often cold, fear-inducing, vampiric; to me it appeared there were two kinds of language used to describe these entities, and they are used disjunctively: on the one hand the language is impersonal and cold, on the other it is violent and anti-human.

In this essay I plan to explore both these linguistic aspects alongside a third, namely how revolutionaries writing in Tricontinental used language to bring to life the futures they wanted to imagine for themselves, the futures they were fighting tooth and nail for.

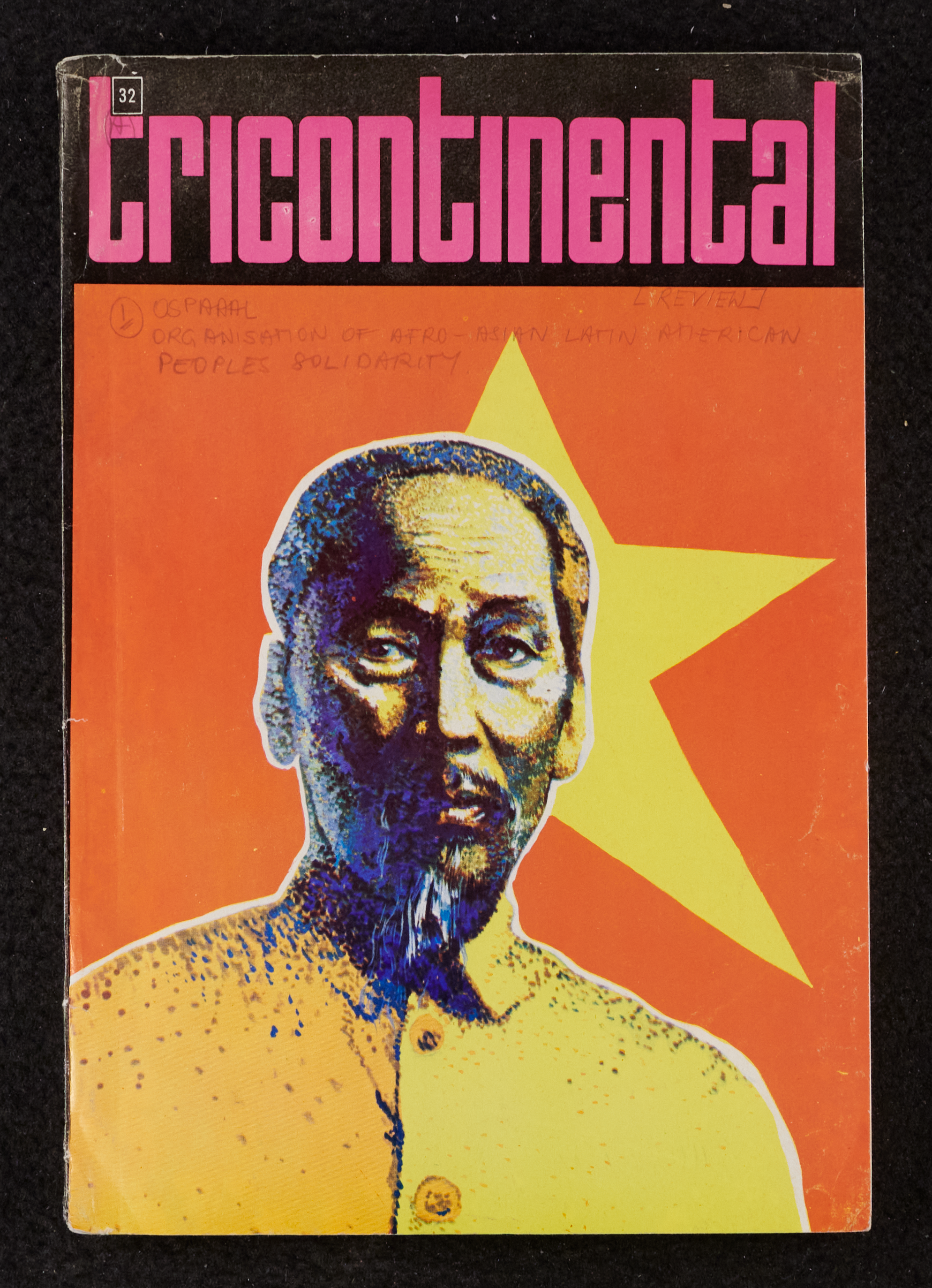

One example from the magazine that stood out to me is from Issue 32, printed in 1972, in an article titled ‘La ley dey tormento’ (in English, ‘The law of torment’).

The article is a report by the Uruguayan National Liberation Movement on the use of systematic torture by the then-present brutal dictatorship, spearheaded by militant leader Juan Maria Bordaberry. The language used to describe both the liberation movement itself, as well as the people it is fighting to protect and emancipate, is one of collective solidarity and joint struggle. For example, the language used to describe the use of torture by the dictatorial regime invokes a spirit of collectivism, ‘The victim, in short, is the Uruguayan people’ and the general violence of the regime targeted at the liberation movement is described as ‘the oligarchy [having] declared war on the Uruguayan people’ (Tricontinental 1972:32, p. 135).

This article is particularly enlightening as it invokes various languages used to describe themselves, their enemies and an imagined future. On an imagined future, the revolutionary authors speak of a people’s victory with the language of inevitability and necessity, writing that despite the intense violent repression from the state ‘the people will inevitably achieve victory’ (‘La ley del tormento’, 1972, p. 135; see also chapter by Danny Millum in this volume). The language the authors use to describe the Bordaberry dictatorship fits with the impersonal and cold disjunct described above; they speak of the threat the regime poses through its will to ‘implement a “Brazil-type” fascism, either by sweeping away all opposition in stages, or by neutralizing their line of resistance until it becomes inoperative’ (‘La ley del tormento’, 1972, p. 136), rendering clear the existential threat the regime holds for the possibility of emancipation.

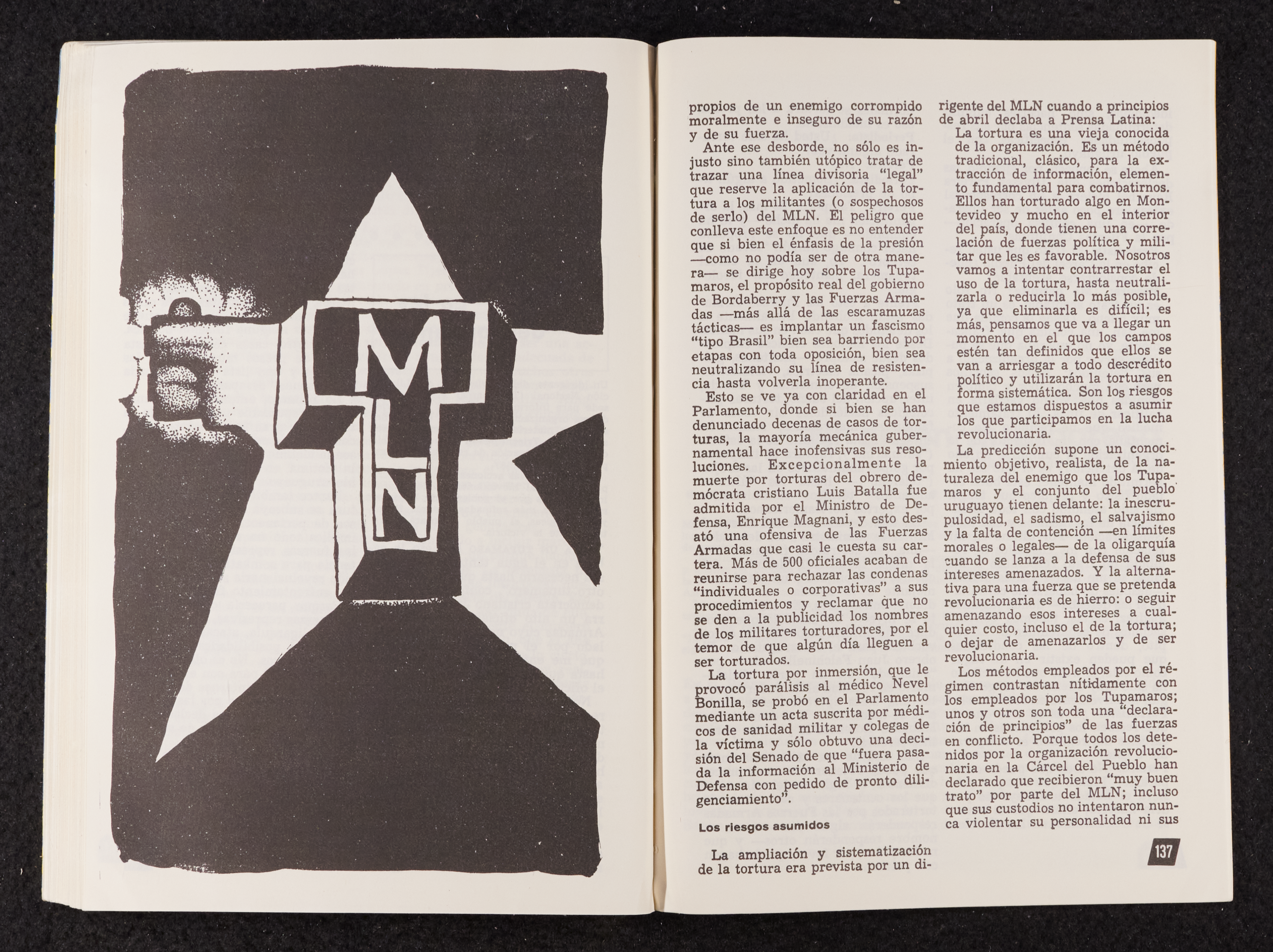

The authors cleverly use contrast to highlight the humanity the liberation movement has, despite fighting a brutal revolution, compared to the inhuman violence of the dictatorship: ‘The methods used by the regime contrast sharply with those used by the Tupamaros; both are a complete “declaration of principles” of the forces in the conflict. Because all those detained by the revolutionary organisation have declared that they received “very good treatment” from the MLN’ (‘La ley del tormento’, 1972, p. 137) this is weaponised against the regime to argue ‘The extension and systematisation of torture is seen as a decree of ideologies’ (‘La ley del tormento’, 1972, p. 138).

The authors further present an image of themselves as steadfast fighters through using this deplorable state-backed injustice against them as rhetoric in their favour: ‘torture is emphasized on those suspected of belonging to the MLN, which implies a forced recognition of the power of the revolutionary organization to organize a frank and loyal confrontation. It would seem that the repressive forces of the oligarchy, armed attacks on the Tupamaros, are not capable of using their military capabilities’ (‘La ley del tormento’, 1972, p. 135). In this case the use of torture against suspected revolutionaries is twisted back against the state to argue that it is a concession showing the fear of the regime for the power the revolutionaries wield, they use it because they know they would lose in general armed combat.

This use of torture is used by the authors to paint a picture of their enemy that is inhuman, depraved and violent, justifying describing them having a degree of ‘unscrupulousness, sadism, savagery and a lack of restraint within more or legal limits… when it launches itself to defend its threatened interests’ [p.137]. This is contrasted with their self-perception as being representatives of the interests of the Uruguayan people, rather than representing the interests of an oligarchal elite. Thus ‘[the torture/prisons functions to] make them serve sentences for their specific responsibilities to the Uruguayan people’ [p.138]; the idea being that for their risky project of emancipating the people of Uruguay the revolutionaries are being punished in the most brutal of ways.

Finally, the authors end with a prophetic account of what this use of torture will result in for those responsible: ‘the hundreds and hundreds of those tortured by the Armed Forces will one day respond or others will respond in their name and that they should not ask them, please, to do so with words’ [p.138]. This paints a picture, linked to the earlier language of inevitability, of justice and retribution against the imperialist regime.

We can use this example to interrogate what kinds of language are used by revolutionaries to describe themselves, their enemies and their imagined futures. The revolutionary movement is contrasted with the Uruguayan state to paint a picture of a movement based in principle, representation and liberation; in comparison to a regime which employs techniques indicative of opposing characteristics, injustice, collective punishment and general cruelty. This allows the authors to use the language of inevitability and justice to imagine a future where this regime is toppled, and in which the people of Uruguay are fate-bound victors in this struggle, who will one day force those responsible in the regime to be held to account: ‘[the regime] demand that the names of the military torturers not be made public, for fear that one day they might be tortured’ (‘La ley del tormento’, 1972, p. 137).

A final example illustrating this use of language is found in issue 103, from 1977, in a piece titled ‘The liberation movement demands…’, which is the edited transcript of a speech by Julio Vives Vazquez, the then-president of the Puerto Rican Socialist Party Delegation, to the Summit Conference of Heads of State or Government of the Non-Aligned Movement.

The language utilised by the author of this article is fantastic in elucidating the way in which national liberation movements perceived themselves, as well as their enemies (in this case the United States). These enemies are denied the use of proper names, being referred to using the terminology of ‘Yankee imperialism’ (Vazquez, 1977, p. 50). The enemies of national liberation are thus denied the opportunity to name themselves, and so denied the humanity that this entails, in response to the nature of their brutal military occupation. Following the logic of this language, the revolutionary movement describes what ought to be done to the ‘Yankee imperialists’ saying that the American occupiers should be ‘blown to bits’ (Vazquez, 1977, p. 56).

In stark contrast to the way in which the American occupation is described, the movement refers to itself through the language of honour, and respect, and they use this same discourse when making reference to other anti-imperialist struggles, such as those in Vietnam. The language being used is that of heroism: ‘The rebel spirit of our heroes lives again among our people’ (Vazquez, 1977, p. 50), with an emphasis on lineage and the impact of colonialism, while the use of the word ‘spirit’ is used as part of a general language of myth and legend. The language of sorority/familial relation is employed when discussing other revolutionary movements: ‘our sister, revolutionary Cuba’ (Vazquez, 1977, p. 53). They also use the language of honour when talking about the people they are fighting for: ‘we fraternally salute the people’ (Vazquez, 1977, p. 57).

Understanding the collection less as a historical archive and more as a living project, I believe, lends credence to the idea that we can use it as a basis to understand and formulate better a concrete identity, through the use of language, for modern anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist movements. Contemporary leftist, anti-capitalist, movements are caught in a crisis of identity, with fractured allegiances and a lack of unity, both in goal and identity. I believe we can use the language from Tricontinental to better understand, and remind ourselves, what it is that unites us in the struggle against imperialism, and what it is that all anti-imperialists fight for.

Tricontinental is a fantastic resource for reminding us of the lessons learnt in the 20th century by anti-imperialists. It also teaches us to approach collections like these as a living resources and cautions us against the temptations of hindsight: ‘The owl of Minerva only takes flight at dusk’ (Hegel, 1896, p.8).

This is ever more important in an age of far-right and neo-fascist advances, which demonstrate the power of the political right to unite around its shared goals, making it even more important for the organised left to organise grassroots opposition. Tricontinental is a vital tool in such an endeavour, as it allows us to recognise the power of language in shaping any anti-imperialist and anti-fascist project.

References

Hegel, G. W. F. (1896). Philosophy of Right. (S. W. Dyde, Trans.). G. Bell & Sons Ltd. (Original work published 1820) https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/hegel/works/pr/philosophy-of-right.pdf

Vazquez, J. V. (1977). ‘The liberation movement demands….’ Tricontinental, 103, 50-57.