13 Visualising global history: An introduction to OSPAAAL’s aesthetics

Alexandra Lewis

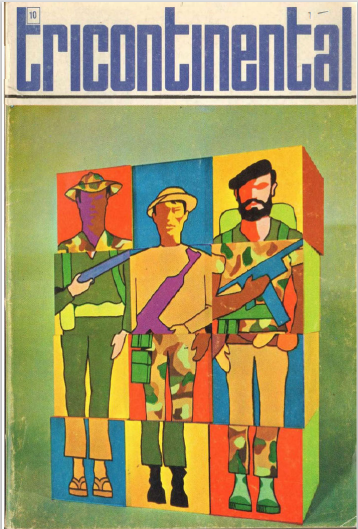

One of the Organisation of Solidarity of the Peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America’s (OSPAAAL’s) main means of communication was the visual content contained within the Tricontinental monthly bulletin and bi-monthly magazine. These journals were distributed globally to 87 countries at peak circulation (Stites Mor, 2019, p.50). They were produced in English, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, Arabic, and French, as these were the languages of the majority of the intended audience (Stites Mor, 2019, p.53). Despite – or perhaps because of – the multilingual text, the most prominent feature of these publications was the bold, bright graphics and striking photographs illustrating accounts of global conflicts and anti-imperial liberation movements (see chapter by Mariano Zarowsky in this volume). The purpose of this chapter will be to argue for the historical significance of OSPAAAL’s visual publications and the consequent need for further research. This chapter will also detail suggested research methods based on my experience as an undergraduate researcher.

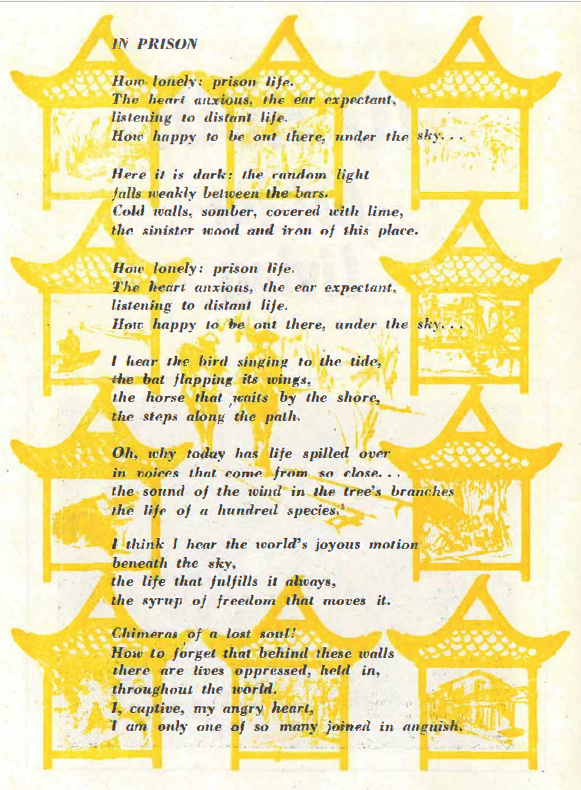

Previously, limited historical analysis has been undertaken concerning OSPAAAL’s aesthetics (Schmiedecke et al, 2024, page 106). Historians often underestimate the value of visual sources due to written analysis being the preferred tradition (Evans, 2012, page 485). However, this chapter argues that these sources can provide invaluable insight into individuals, organisations, and events by bypassing the language and censorship constrictions of the written word. Visual content can also capture the atmosphere of specific periods in a more animated way than written sources through their use of imagery and colour. For example, graphics such as figure 6 visualise solidarities between geographically distant conflicts with an immediacy that would take pages of written words to achieve. It is for these reasons that visual publications should not be relegated as adjuncts to written sources but instead be used as a central focus of historical analysis. To apply this rationale to OSPAAAL’s visual content, further research on Tricontinental and its aesthetics is vital to fully understanding the organisation’s role in the creation of anti-imperial communities and solidarities within the Global South.

Produced in Havana, these sources cover Cuban, Global South and anti-imperialist history for the period following the inaugural Tricontinental conference in 1966. OSPAAAL’s closure in 2019 was considered a significant loss within the field of global history as it represented the end of a landmark international organisation which advocated for revolution and decolonial practices in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Archivists involved in the creation of such publications went as far as to state that the aesthetics of the Tricontinental should be considered as a ‘world heritage site’, and it is certainly the case that these journals contain a rich socio-political history portrayed through extensive visual means seldom found in other historical primary sources (Camacho Padilla & Palieraki, 2019, page 416).

As OSPAAAL’s graphics were produced in Cuba with financial and bureaucratic support from the state, the specific Cuban ideal of an anti-imperialist, socialist worldview directly influenced the content of OSPAAAL’s visual publications (Mahler, 2018, page 10). OSPAAAL’s art differed from that of other communist countries, such as the USSR, as pop art style pieces were favoured over social realism. This style was chosen to repurpose capitalist, commercial advertising methods to promote the ideology of the anti-imperialist revolution. The aim was to create what Tricontinental director Alfredo Rostgaard called the ‘anti-ad’ which directly subverted the capitalist advertising method of the West (‘The Art of the Revolution will be Internationalist”, April 2019, page 14). Figure 1 is a pertinent example of this as it portrays OSPAAAL’s opposition to Western capitalism through the imagery of burning the brands of famous Western companies. In this way, the aesthetics of the Tricontinental are unique as they display a break from previous communist artistic tradition and indicate a separate genre of anti-imperialist art.

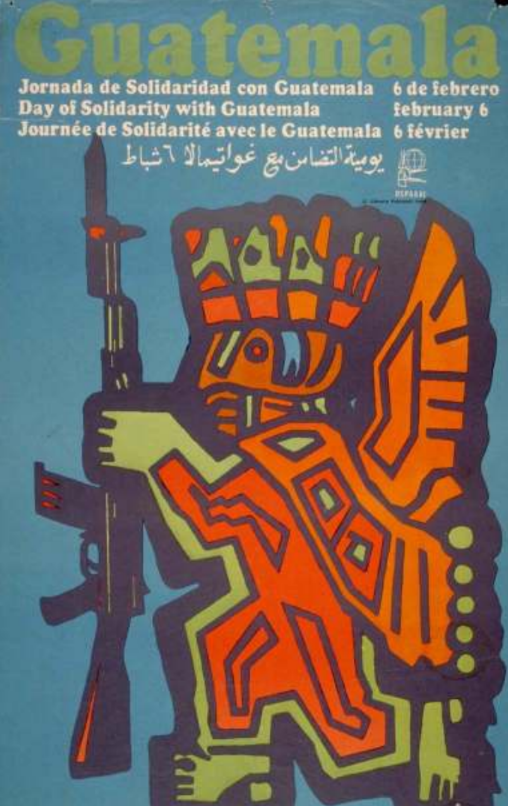

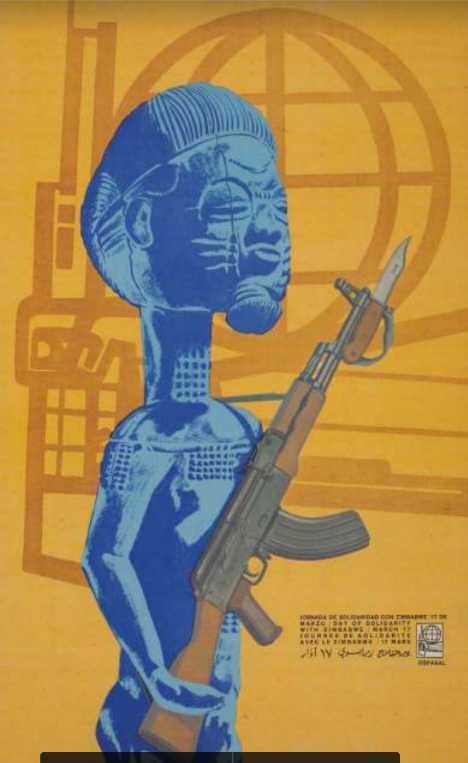

OSPAAAL’s visual publications represented an alternative to Western paternalism as they were not simply produced for the combatants in question but with them. Genuine transnational solidarity was fostered through the use of content sent in by delegations, as well as dialogue with the organisation’s member countries to create graphics that accurately represented the cultural identity and struggles of specific conflicts (‘The Art of the Revolution will be Internationalist”, April 2019, page 23). For example, a Cuban delegation met with Yasser Arafat after the atrocities of the 1967 Six-Day War to discuss how Cuba could play a role in supporting Palestinian nationalism (Camacho Padilla & Stites Mor, 2013, page 173; Karsh, 2017, page 1). Furthermore, OSPAAAL dedicated specific days and visual content to days of solidarity with specific liberation movements. This can be seen in Figures 2 and 4, which detail days of solidarity with the peoples of Guatemala and Zimbabwe respectively. This further highlighted OSPAAAL’s commitment to genuine solidarity over paternalism as each issue was highlighted for members of other conflicts to draw on similarities and develop ideological and material solidarities.

OSPAAAL used generalised iconography to create a sense of concurrence and shared values between regionalised conflicts to promote the ideology of a shared anti-imperialist liberation struggle. In Figure 2, three figures are adorned with uniforms which are characteristic of combatants from Africa, Latin America, and Asia, the three continents represented within the Tricontinental. These types of uniforms would have been recognisable from the photographs OSPAAAL published alongside graphics in the Tricontinental Bulletins (see, for example, Figure 7). The combination of the combatant icon, with the heads, bodies and legs of the soldiers swapped around ‘magic cube’-style, infers OSPAAAL’s vision of a shared global fight against imperialism as it suggests that each soldier is synonymous with one another. Figure 2 is an example of the community OSPAAAL aimed to create through their graphics as combatants from Africa, Asia, and Latin America are depicted in a Cuban artistic style as participating in similar liberation struggles.

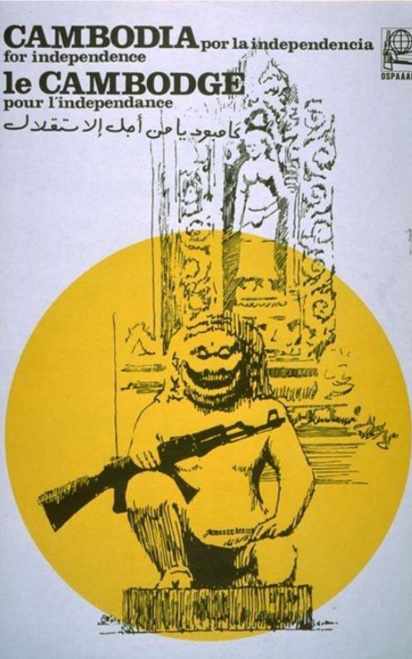

Another prominent, generalised symbol used across the Bulletins was the AK-47. The AK-47 or Kalashnikov was developed in Moscow in 1947 as a standardised USSR weapon (Kinney, 2023, page 288). Cuba itself worked with the Soviet military in contexts such as the Angolan liberation movement (Shubin & Tokarev, 2001, page 613). However, as revolutionary groups in the Global South regularly used the gun for conflicts unaffiliated with the USSR, the AK-47 became a symbol of the shared, global, anti-imperial struggle and collective identity (Kinney, 2023, page 284). This is explicitly seen in Figures 3, 4, and 5 as the rifle is paired with contextual symbols of the respective struggles. Despite the different socio-cultural context, OSPAAAL’s visual publications connotate a collective struggle against a collective imperial enemy, through the use of the Kalashnikov.

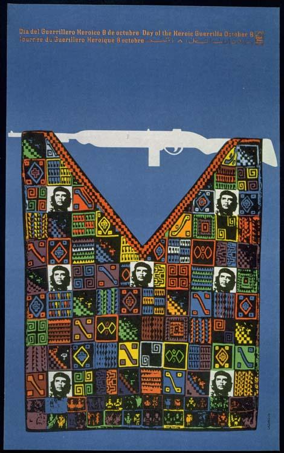

As well as the generalised images of combatants and AK-47s, specific regional symbols were also rendered within the style of the ‘anti-ad’ to bolster the visibility of distinct anti-imperial struggles (“The Art of the Revolution will be Internationalist”, April 2019, page 14). Regional [and cultural-nationalist] symbols were also often combined to visualise solidarities between revolutionary groups. This is seen in Figure 6 as the image combines the cultural symbol of the sarape (a Mexican peasant vest), tatreez (Palestinian textile art), and the figure of Che Guevara (a prominent Cuban revolutionary figure) (Padrón, 1970, “Day of the Heroic Guerilla”). This combination knits together Palestinian nationalism, resistance to oppressive Mexican military regimes, and the Cuban revolution within one singular image (Karl, 2014, page 727). As discussed earlier in the chapter, it is in this way that visual publications are uniquely capable of immediately displaying complex and nuanced concepts in an accessible manner.

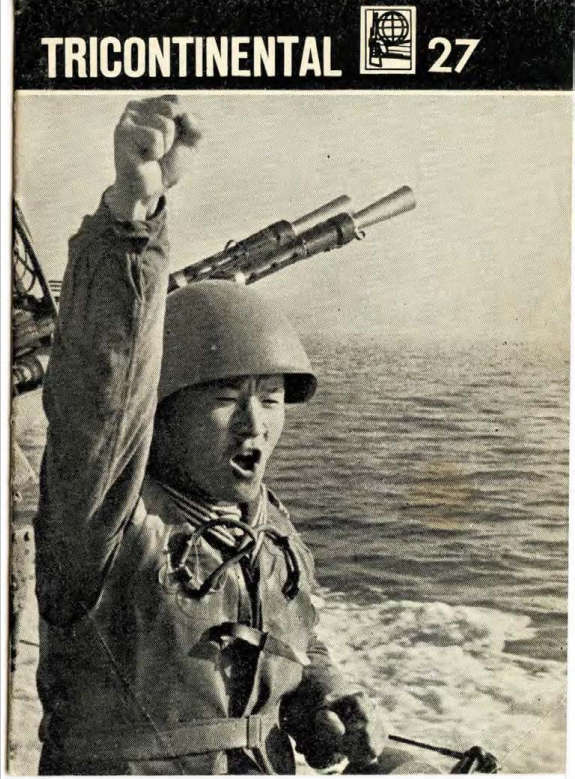

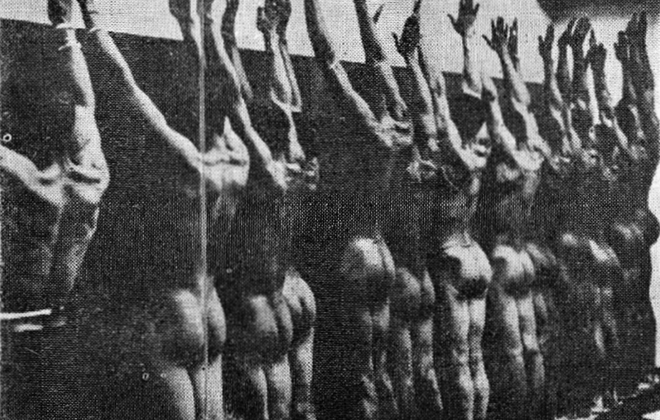

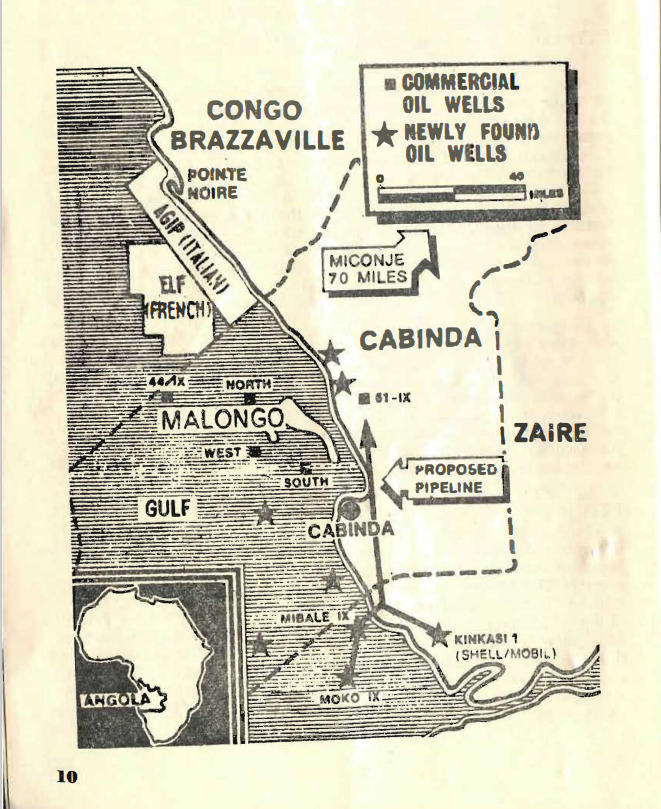

Aside from revolutionary graphics, OSPAAAL’s visual publications also included explicit photographs of ongoing anti-imperial conflicts. Figure 7 portrays a celebratory North Korean combatant with the caption ‘The Korean people are ready to defeat all provocations’. Triumphant photographs such as Figure 7 were used to portray a positive attitude toward the possibility of defeating imperial powers and achieving the leftist world order that Cuba envisaged. The publication of these images served as a news source for others engaging in similarly-minded, anti-imperial struggles. Explicit photos of ongoing conflicts were published to circulate news of atrocities to other global, anti-imperialist groups. For example, Figure 8 displays atrocities committed against what OSPAAAL called ‘South African patriots’ (Tricontinental 29, 1968, page 49) who have sought to combat the apartheid state. Similarly, Figure 9 shows destruction caused by Israel’s invasion of Southern Lebanon in 1972. These photographs were used by various revolutionary groups to provide an education on other leftist global conflicts. In another dimension, pragmatic images such as maps, displayed in Figure 10, aided the education of anti-imperialist groups on their counterpart’s struggles. Black Panther leader Stokely Carmichael went as far as to call the Tricontinental Bulletin ‘a bible in revolutionary circles’ (Tricontinental, 2019, page 5). The use of its visual publications as a source of information within revolutionary circles evidences the success of OSPAAAL’s overall aim of bridging global anti-imperialist movements and creating a sense of connection.

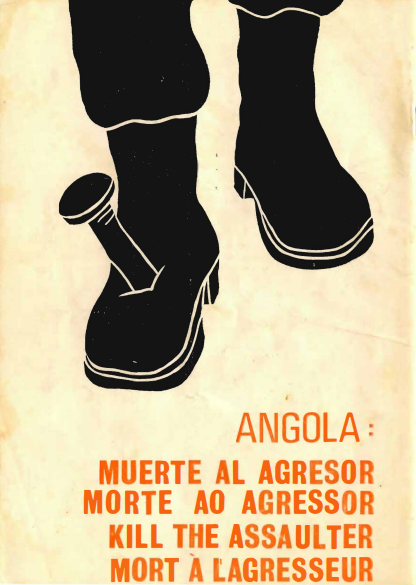

OSPAAAL’s visual publications also provided an ideological framework for Cuba’s material support for international liberation struggles (Schmiedecke et al, 2024, page 104). For example, after the invasion of Angola by South African troops in October 1975, Cuba increased its military support by sending thirty thousand troops to support the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) (Mahler, 2018, pages 176-177). This was reflected in the publication of a dedicated Angolan issue of the Tricontinental Bulletin in 1975. This included visuals such as Figure 11, which conveyed and justified Cuba’s anti-apartheid military intentions in the region.

The aesthetics featured in the Tricontinental Bulletins can also be considered as a reflection of geopolitical developments. For example, they can be considered as documentation of the effects of the economic blockade enacted by the United States on Cuba. A shortage in artistic resources caused by the blockade resulted in artists innovating creative solutions. This often included cutting printed letters from magazines, images from catalogues and printing posters and bulletin issues on newspaper back issues (“The Art of the Revolution will be Internationalist”, April 2019, page 19). A repetitive artistic method was also used to make effective use of the limited resources within Cuba due to the blockade (Victoria and Albert Museum [V&A], 2022-2023). For example, Figure 12 uses a repetitive, bright print to fill the page with minimal resource use. Use of colour was also limited, for example, the interior of Bulletins were commonly published in black and white (see Figures 7, 8, 9 and 10). Therefore, it is not just the content of OSPAAAL’s visual publications which holds historical value but the very method of their creation.

As visual publications are easily reproducible and understood, they can infiltrate circles in which written or verbal communications are restricted. In the specific case of OSPAAAL, visual publications were able to circulate in countries where officials were often not allowed to spread the ideas of anti-imperialist revolution (Tricontinental, 2019, page 16). OSPAAAL’s aesthetics also upheld the iconography of revolutionary movements at times when that iconography was censored in the country in question. For example, visual publications (such as Figure 13) continued to use the colours of the Palestinian flag at a time when the Israeli government had banned the use of the Palestinian flag and its associated colours (Lionis & Hourani, 2024, page 148). Therefore, visual publications can be considered a unique tool to continue the circulation of revolutionary ideas when the use of written and verbal channels became potentially dangerous.

On the inside front cover of every Bulletin, OSPAAAL reiterated its commitment to the dissemination of revolutionary information via its publications by stating that the organisation ‘authorises the total or partial reproduction’ of its content (Tricontinental Bulletin 37, 1969; see also chapters by Alice Corble and by Karen Smith in this volume). These publications chronicled OSPAAAL’s efforts to expand the revolution globally and are a unique tool in understanding the ideology behind the leftist, Cold War political scene (Camacho Padilla & Palieraki, 2019, page 417). This is not to say that OSPAAAL’s aesthetics are the only record of such ideologies, publications such as Mujeres and Jeune Afrique also promoted a similar leftist worldview (see chapters by Bethany Collard, and by Tobey Ahamed-Barke, in this volume). Individual liberation movements also had their own publications and circulated similar imagery. However, OSPAAAL is a key example of a continuous, multi-lingual, leftist, visual publishing organisation which recorded attitudes and opinions throughout the Cold War. Therefore, OSPAAAL’s visual publications are an invaluable historical source which deserves extensive academic attention.

Notes on practical research methods using the OSPAAAL archives at the University of Sussex

As an undergraduate dissertation researcher, I found that OSPAAAL’s visual content differed significantly from the primary sources that I had previously analysed. British historical education has a tendency to overlook both global histories and the use of visual sources. Therefore, I would encourage any history student that has experienced a narrowed, Eurocentric historical education to engage thoroughly with the Tricontinental archives.

As a student at the University of Sussex, I was able to use the physical British Library for Development Studies Legacy Collection, the online Freedom Archives and the online Palestine Poster Project Archives. Due to the dispersal of resources, I found it useful to create well-organised and well-informed notes. The most effective way to do this was by creating a table detailing the source’s location, a figure number, a photograph of the source, date, author, publisher, issue number and apparent themes. It is important to note that due to OSPAAAL’s anti-imperial and anti-US values, copyright laws were often not followed. It is therefore commonplace to find that most visual publications, especially those found within the Tricontinental Bulletins, do not feature artists’ names or any other information. Thus, it is vital to record the available information, for both personal ease and accurate referencing.

Example

|

Figure |

Source |

Location |

Date/Author/Publisher/Issue |

Themes |

|

1 |

|

BLDS |

OSPAAAL Tricontinental Issue 117 Pg.15 |

Keffiyeh PLO Olive Branch |

I found it particularly useful to identify key themes as I researched as this aided the formulation of my arguments by marking where examples of specific symbols could be found. For example, my dissertation revolved around symbols of Palestinian resistance and transnational solidarity. Therefore, I consistently made notes of recurring themes such as the keffiyeh, the AK-47 and the colours of the Palestinian flag. This helped both in re-finding specific images but also in making connections which further developed my arguments.

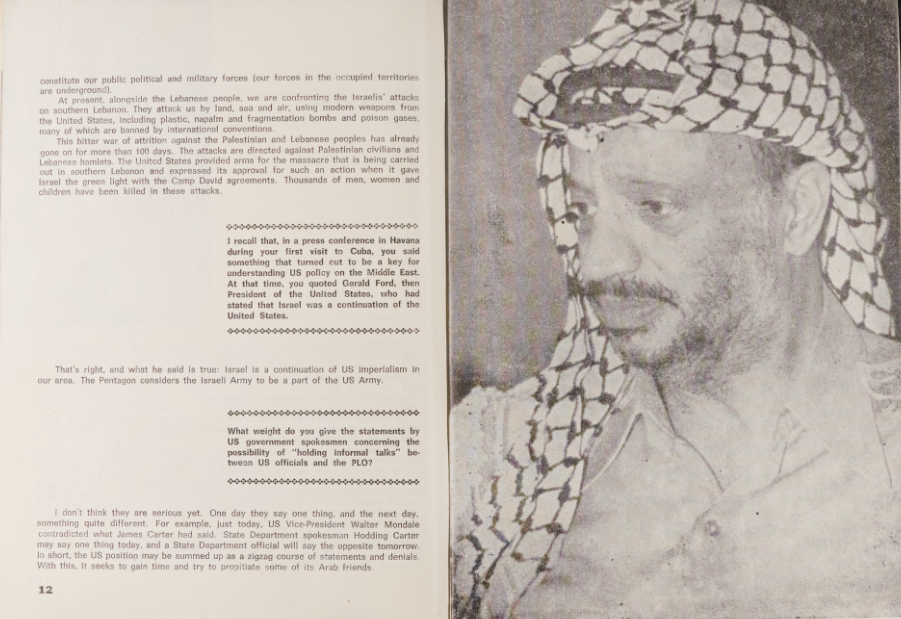

Moreover, whilst I advocate for the centrality of visual sources within historical analysis, it is important to note the value of using written sources alongside the graphics and photographs. Invaluable material such as interviews and news reports surround the graphics on the pages of the Tricontinental Bulletin and give context which allows for a deeper understanding of the images. For example, the image of Yasser Arafat in Figure 14 is a compelling image of Palestinian resistance when viewed alone. But, when the image is paired with the text on the surrounding pages which detail an in-depth interview with Arafat, the image and its place within the bulletin are further contextualised. Therefore, while I argue for the centrality of Tricontinental graphics in historical analysis, I found it useful in my research to use the bulletins in their entirety.

On the subject of complementary written sources, secondary written sources in the form of academic articles and books were vital to my understanding of OSPAAAL’s visual content. Visual content can also be found by looking at secondary sources as at times academics have had access to archives that undergraduate researchers will not have seen. This content also usually comes with a specified analysis of the given image and is therefore greatly beneficial to researchers.

In conclusion, OSPAAAL’s visual publications represent a rich history of anti-imperialist political thought and Global South solidarity from the Cold War to the near present. The historical analysis of Tricontinental’s aesthetics reflects a unique insight into nuanced discourses surrounding regionalised and global conflicts. This chapter has been written in the hope that it will be a useful starting point for other researchers, especially undergraduates, who wish to research not just the aesthetics of OSPAAAL but also other similarly rich visual resources.

References

Camacho Padilla, F., & Palieraki, E. (2019). Hasta siempre, OSPAAAL! Closing its doors after over half a century of promoting internationalism from Havana, the Organisation of Solidarity with the Peoples of Africa, Asia, and Latin America leaves a historical and artistic record of unprecedented Third World solidarity. NACLA Report on the Americas 51(4), 410-421. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714839.2019.1693002

Camacho Padilla, F., & Stites Mor, J. (2023). Presence and visibility in Cuban anticolonial solidarity: Palestine in OSPAAAL’s photography and poster art. In S. Thomson and P. V. Olsen (Eds), Palestine in the world: International solidarity with the Palestinian Liberation Movement (pp. 167-196). I.B Tauris & Company Ltd.

Evans, J. (2012). Historicising the visual. German Studies Review 35(3), 485-489. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43555793

Karl, S. (2014). Rehumanizing the disappeared: Spaces of memory in Mexico and the liminality of transitional justice. American Quarterly 66(3), 727–48. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43823427

Karsh, E. (2017). The six-day war: An inevitable conflict. Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies, 1-11. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep04623

Kinney, B. (2023). “The rifle is the symbol”: The AK-47 in Global South iconography. Journal of World History 34(2), 277-314. https://doi.org/10.1353/jwh.2023.a902055

Lionis, C., & Hourani, K. (2024). The watermelon flag: Solidarity, subversion, and sumud. In International Research Group on Authoritarianism and Counter-Strategies & kollektiv orangotango (Eds.), Molotovs – a visual handbook of anti-authoritarian strategies (pp. 148-151). Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag. https://www.jstor.org/stable/jj.13568050.24

Mahler, A. G. (2018). From the Tricontinental to the Global South: Race, radicalism, and transnational solidarity. Duke University Press.

Padrón, L. A. (1970). Day of the heroic guerilla. The Palestine Poster Project Archives. OSPAAAL. Day of the Heroic Guerrilla | PPPA (palestineposterproject.org).

Schmiedecke, N. A., Zerwes, E., & Generoso, L. (2024). Reframing revolution and solidarity: Photography and visual culture in OSPAAAL poster art (1967–1990): Reencuadrando revolución y solidaridad: fotografía y cultura visual en los carteles de la ospaaal (1967–1990). Bandung 11(1), 102-140. https://doi.org/10.1163/21983534-11010001

Schmiedecke, N. A. (2023). Oppressed, resistant, and revolutionary: The Third World as designed in the OSPAAAL graphic art. Antitheses 16(31), 251-291. http://dx.doi.org/10.5433/1984-3356.2023v16n31p251-291

Stites Mor, J. (2019). Rendering armed struggle: OSPAAAL, Cuban poster art, and South-South solidarity at the United Nations. Jahrbuch fu Geschichte Lateinamerikas 56, 43-50. http://dx.doi.org/10.15460/jbla.56.132

Tricontinental. (2019). The art of the revolution will be internationalist (Dossier no. 15). Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. https://thetricontinental.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/190408_Dossier-15_EN_Final_Web.pdf

Victoria and Albert Museum [V&A]. (2022). Solidarity and design: An introduction to OSPAAAL. Produced as part of the exhibition ‘OSPAAAL: Solidarity and Design’ at V&A South Kensington, 17 September 2022 to 31 March 2023. https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/solidarity-and-design-an-introduction-to-ospaaal

Shubin, V., & Tokarev, A. (2001). War in Angola: A Soviet dimension. Review of African Political Economy 28(90), 607–18. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4006840