15 Grounding research in reality: Undergraduate dissertation research with pan-African periodicals

Tobey Ahamed-Barke

No matter how conscious we try to be of the contexts we live in and the knowledge we possess in the present, we write history with hindsight. What we choose to focus on, how we present a narrative, and how we write are shaped by our values and the retrospective chronology that we impose on history (see chapter by Danny Millum in this volume). However, this can result in narratives of inevitability and ahistoric, teleological interpretations of the past. During my undergraduate studies, I have found that contemporary, non-academic periodicals, such as magazines and newspapers from the period I am studying, can help challenge this teleological tendency (see chapter by Bethany Collard in this volume). Rooted in the immediacy of the past, these periodicals reflect contemporary perspectives that can help us resist the tendency towards hindsight, while their proactive discussion of current events for a public audience mean they usefully both discuss the details of contemporary issues in depth and reflect contemporary understandings about these topics. Sussex Library holds many collections of contemporary periodicals on a range way of topics and from a range of periods and locations, so they are not just beneficial, but one of the most accessible sources to Sussex students. Nonetheless underutilised by students who rely evermore on digital sources and online searches, these physical contemporary periodicals can broaden our horizons beyond the digitised and can help prevent us from seeing history as a fixed, linear trajectory, and recover contemporary emotions and concerns.

Last year, I spent an afternoon reading through sources from the British Library for Developmental Studies Legacy Collection, held at the University of Sussex Library. This was initially for my dissertation on the international dimension of the Algerian War for Independence; I had read an article that cited an issue of the Pan-African serial Jeune Afrique, so I got in touch with Sussex Library, hoping they might have it. Although their Jeune Afrique collection unfortunately ended one year short of this issue, Bethany Collard, the librarian who specialises in Sussex’s collection of non-official serials, collated other Jeune Afrique issues relating to Algerian history for me to read. While I still used these issues to enrichen my dissertation, I primarily saw this as a more general opportunity to work with a type of physical source that was new to me. The articles were fascinating, and they helped me to see the advantages of contemporary magazines for grounding research in the ‘realities’ of the past. When it came to discussing primary source work within the ‘Tricontinental, Mujeres, and the worlds they invite us to imagine’ project that informed this sourcebook, I realised that the approaches I had encountered with Jeune Afrique were relevant to periodicals like Tricontinental too, so it was suggested that I contribute an article based on these insights to this sourcebook. While some of my thoughts are not unique periodicals but might apply to other kinds of primary material, it is the specific nature of periodicals as sources that proactively discuss current affairs for a public audience, and the abundance of periodicals housed at Sussex, that makes them the particular focus of this article.

The Jeune Afrique issues that Bethany identified were from between 1969 and 1979, so they were useful sources on Algeria’s political history post-independence in 1962. I was fascinated by the articles about Ahmed Ben Bella, the Algerian nationalist and politician who was Algeria’s President during the mid-1960s. He had been one of the founders of the Algerian ‘National Liberation Front’ (FLN), the nationalist organisation that launched the Algerian War for Independence (1954-62) against French colonial rule, and on August 4, 1962, a month after independence was achieved, he seized power in a coup d’etat against the leader of the provisional government and fellow FLN founder, Benyoucef Benkhedda. However, just three years later, on June 19, 1965, Ben Bella was himself overthrown by his defence minister, Houari Boumédiène, who kept him under house arrest for the following 14 years. Reading Jeune Afrique articles spanning both before and after Ben Bella’s release in 1979, following President Boumédiène’s death, was thus an enriching experience for understanding perceptions of his situation.

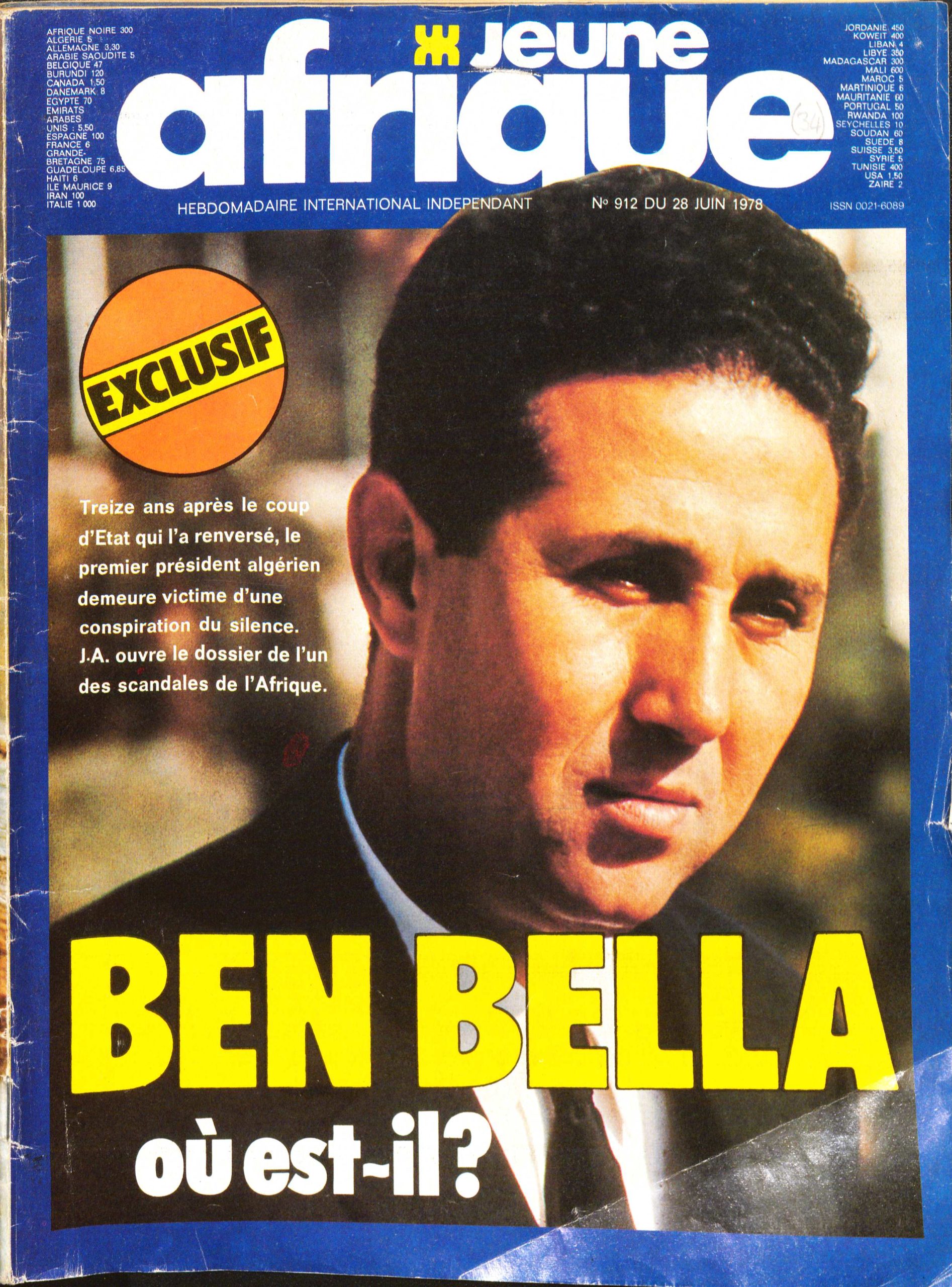

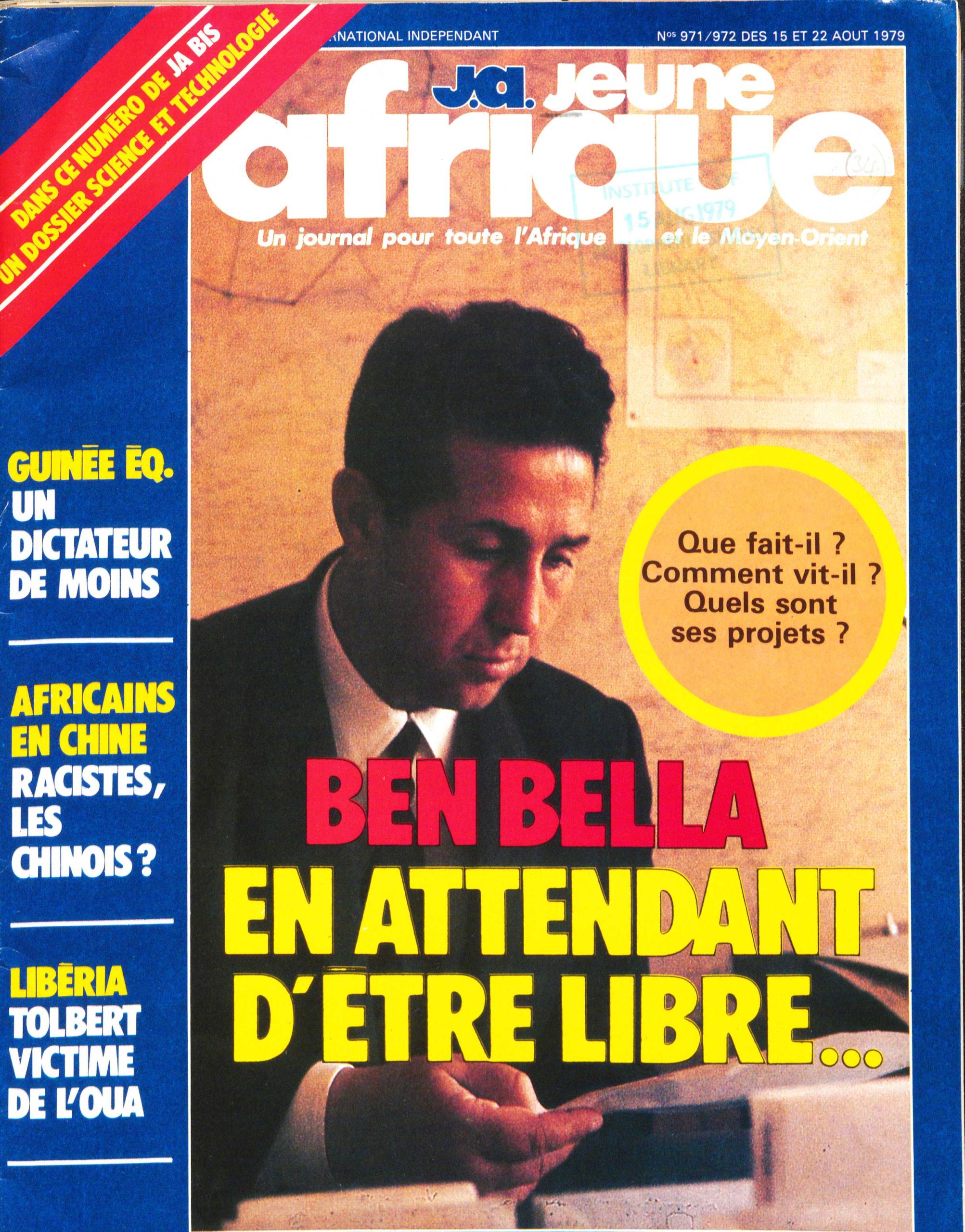

One particularly memorable issue, from 1978, contained a series of articles by several authors investigating the ‘mystery’ of Ben Bella’s arrest (see Jeune Afrique, 28 June 1978). They questioned why he had been arrested, yet not killed, and criticised the ‘silent consent of all those in the Arab and African worlds who embraced Ahmed Ben Bella and yet have remained silent’ about his imprisonment. The sense I had while reading this was like dramatic irony, knowing that President Boumediene would die later in 1978, and the process of Ben Bella’s release would begin the following year. After years of imprisonment, the hope in the 1978 articles for Ben Bella’s freedom would be realised just one year later, as reflected in articles published in 1979 that reported that steps had finally been taken towards his freedom. The criticisms over the culture of silence around his arrest would also have their resonance in these later Jeune Afrique articles, which lamented how his release had been done quietly, in fear of the political agitation that his release could have instigated against the incumbent President’s one-party state (Buchet, 1979b; Zaïdi, 1979).

I felt this sense of ‘dramatic irony’ again in an article from April 1979, just three months before the start of Ben Bella’s release, in which his lawyer confirmed that there were still no signs that he would be released (Selhami & Zaïdi, 1979). However, this feeling also showed me something important: I was reading with hindsight. When we look back at the past, we know what is going to happen next, so we risk projecting these ‘outcomes’ onto preceding events and treating them as ‘predestined’. This is something that students have to grapple with as we learn to write history in more nuanced ways, though this tendency is also visible throughout academic historiography, in allusions to ‘inevitability’ and narratives of progression. Contemporary periodicals remind us that this is not how history is experienced in the moment though, as their authors cannot have foresight in the way that historians write with hindsight. Focused on current events, they write about the same issues that become part of historical inquiry, but without knowing what will follow, and the experience of reading these more immediate accounts challenged the way I saw Ben Bella’s history. The Jeune Afrique periodicals could only speak to the moment they were immersed in, so their inability to anticipate Ben Bella’s release challenged my implicit notion that history was marching towards his release. It might seem obvious to say that people are not prescient, but knowing it and embodying it in your research are different, and I found that using contemporary periodicals helped me to move from the former to the latter. It is important not to frame people as precursors to their own future – like suggesting that these journalists were writing ‘in the year before his release’ – as this is not how they could define themselves, and this risks patronisingly denying their subjectivities and lived experiences. The experience of reading people discuss their current affairs makes it usefully obvious that history is not a string of inevitable moments, each neatly building towards the next, but a messy set of immediate experiences.

Contemporary periodicals also help to resist colouring the past with our own assumptions by highlighting contemporary concerns and emotions. This observation can be true of most primary material, but by discussing current affairs for a public audience, periodicals particularly effectively reflect contemporary perspectives on ongoing issues. For example, the articles I read discussed how Ben Bella’s name had been virtually ‘forgotten’ due to a culture of silence around his arrest that had arisen in Algeria and abroad. This might reflect contemporary hopelessness around the cause of Ben Bella’s freedom, as the journalists felt it lacked momentum and popular support, but coupled with the decision to dedicate so many pages to an investigation into Ben Bella in 1978, it may also indicate a sense of urgency and even hope to inspire more interest in the cause, enough to spend several pages discussing Ben Bella years after his arrest. In the words of Hamid Barrada, author of one of the articles, the pieces were ‘intend[ed] to break this quiet complicity’ in his imprisonment (Barrada 1978). In this way, reading the contemporary articles in Jeune Afrique helped to cement my understanding of Algerian political history in contemporary attitudes around his house arrest, rather than constructing my own meanings out of his release. The physicality of periodicals is particularly relevant to this too, as decisions about what to publish, how much space to give a topic, where items are placed in a given issue, and what gets placed on the front cover all reflect contemporary attitudes. Not just the text of isolated articles, but periodicals as a whole provide valuable insight into what topics were considered worth reporting and fighting for, proving their specific value as physical sources. They can show subtle or dramatic shifts in emotions, and reveal how issues were given importance, which might not match assumptions of importance that we make in retrospect (see chapter by Mariano Zarowsky in this volume).

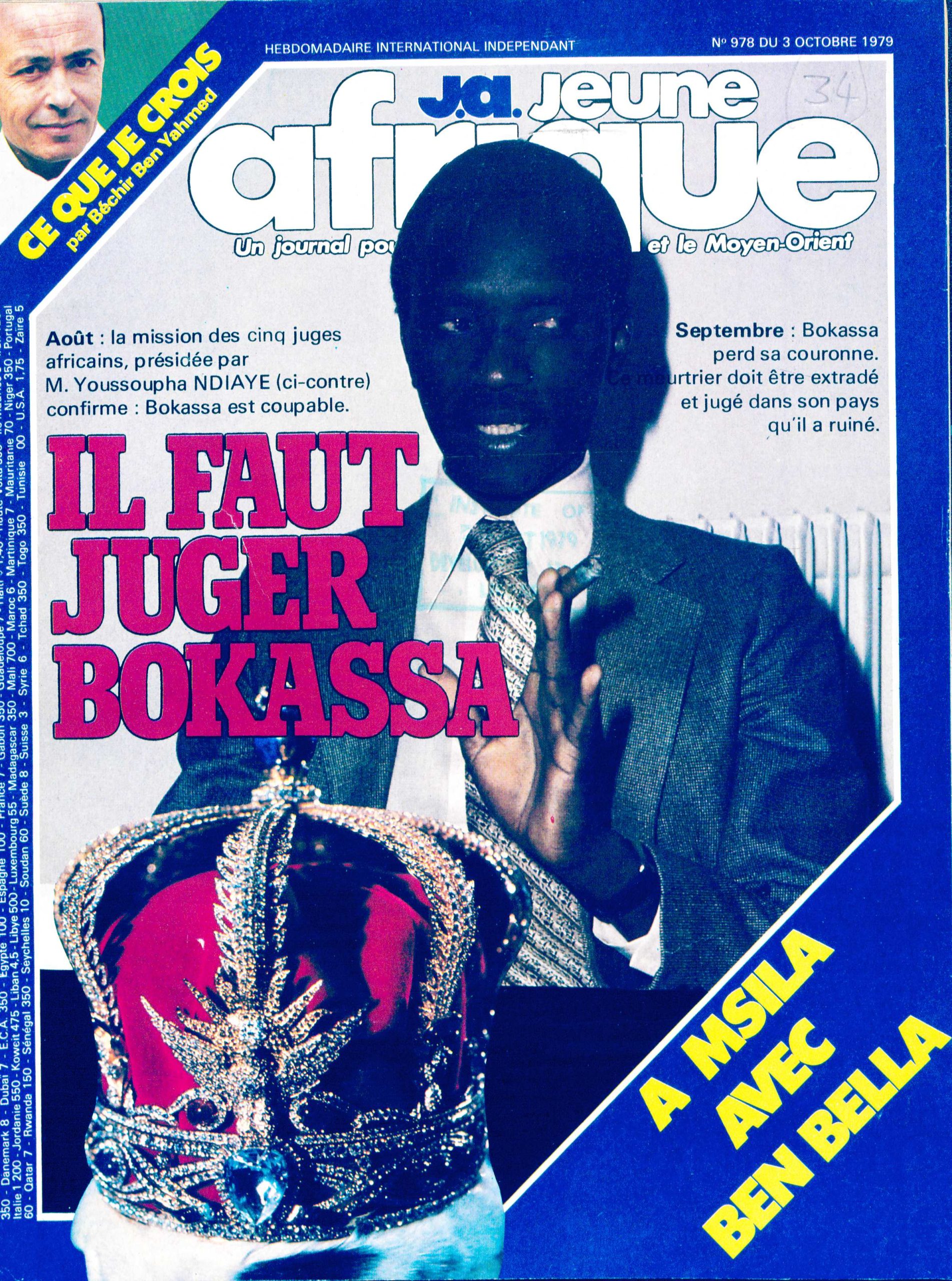

Beyond the Ben Bella articles, these issues also broadened my understanding of other areas of history. For instance, I encountered several mentions and front cover photos of Jean-Bédel Bokassa, the dictator who ruled the Central African Republic until 1979 (Buchet, 1979a; cover of Jeune Afrique, 1979, October 3, Figure 3 above). His was not a name I had come across before, so encountering so many mentions of him provided an impetus to learn more about him. This has introduced to me a history I was unaware of, so I appreciate how contemporary periodicals can teach you about topics beyond your narrower field of study. Just as historians should read the news and stay up to date with current affairs, looking at historic newspapers and magazines improves a historian’s awareness of broader contexts in which ‘history’ happened. This facilitates a beneficial contextualisation and helps with analysis of ‘connected histories’, rather than reinforcing the isolation of communities, regions, and fields of study (Subrahmanyam, 1997). Even if the connections might not seem obvious, disparate events occur through the same wider contexts, and audiences consume disparate events simultaneously. Globally-minded publications like Jeune Afrique are useful for global history, as they reflect how international issues intersect directly and for contemporary readers; seeing articles about Palestine, Algeria, and the Central African Republic together helps resist the tendency to study along purely national lines, as news and politics are not confined by borders. However, periodicals exist from the largest regional scales to the smallest, so while my focus was on an international publication, the same approach can be taken using local community magazines or magazines for communities of non-regional identity, like sexuality. Periodicals broadly help to situate your research topic in the world around it.

As fascinating as these realisations were, I did ultimately access the Jeune Afrique issues to help with my dissertation, and thankfully, they were beneficial in this regard too. While many of the issues were not directly relevant, among them was an article by Mohamed Boudiaf. Boudiaf was another founder of the nationalist FLN organisation, and his piece had precise details on the international dimension of the conflict. It gave me a much better understanding of the contexts around my dissertation topic. I would not have found this article online, so even aside from the benefits I found contemporary periodicals brought to my thinking, I gained a fundamental appreciation for physical sources for ‘filling in gaps’ in my knowledge of my area. Students like myself default to online searches and sources, but there is a wealth of material that you cannot access online. You need to go beyond what online sources provide, and you should not expect every individual article to be catalogued online either. If you are unsure where to start, librarians can help you to navigate the collections and find relevant material, as Bethany so helpfully did for me. You do not know the helpful source you might find until you try, so going beyond the precisely catalogued online sources to handle physical ones, like magazines and newspapers, can be enriching in unexpected ways.

Contemporary periodicals ground research in reality. They can help historians see how issues were perceived at the time, which helps to reframe research away from teleological assumptions about importance. They do not grant unmediated access to past public opinion, as their authors portray this according to their own perspectives and aims; like any source, they should be used with awareness of their limitations. Nonetheless, contemporary periodicals are valuable for uncovering contemporary attitudes and emotions, and they remind the historian that history is not experienced as inevitable.

References

Barrada, H. (1978). Mystère et Scandale. Jeune Afrique, June 28, 30-31.

Boudiaf, M. (1976). Les préparatifs du 1er novembre 1954. Jeune Afrique, November 12, 22-25.

Buchet, J-L. (1979a). Les limites de l’ouverture. Jeune Afrique, June 20.

Buchet, J-L. (1979b). Ben Bella fait toujours peur? Jeune Afrique, July 18, 28-29.

Selhami, M., & Zaïdi, J-M. (1979). Algerie: Les petits pas. Jeune Afrique, April 18, 19.

Subrahmanyam, S. (1997). Connected histories: Notes towards a reconfiguration of Early Modern Eurasia. Modern Asian Studies 31(3), 735-762. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X00017133

Zaïdi, J-M. (1979). Ben Bella en attendant d’etre libre. Jeune Afrique, August 22, 18-19.

About the author

name: Tobey Ahamed-Barke

institution: University of Sussex

Tobey Ahamed-Barke is a Master’s student studying Contemporary History at the University of Sussex. He has an interest in the global history of decolonisation and the internationalisation of anticolonial movements, with a particular focus on the history of the Third World at the United Nations. Through his role as a Race Equity Advocate for the Faculty of Media, Arts and Humanities, he is also involved in work to improve the inclusivity of Sussex and its curricula.