14 Applying Tricontinental’s ‘Minimanual of the urban guerilla’ to contemporary political activism

James Watts

Issue 56.

At first glance, it might not stand out particularly from other issues of Tricontinental, with its faded electric blue cover, a topographical map of a city and a haphazardly-drawn oval around the notorious Brazilian prison Carandiru. It is certainly not as bold as other issues whose covers feature machine gun-wielding soldiers or protesters with their fists in the air calling for freedom. However, this unassuming issue is an invaluable guide for contemporary political activists. Published in November 1970, it was written by Carlos Marighella, a Brazilian guerilla fighter and Marxist who was assassinated by Brazilian security forces the year before the publication. This issue was published in his honour and marked the one-year anniversary of his death; enclosed in Issue 56 is his Minimanual of the urban guerilla.

I first connected to the BLDS Legacy Collection during a third-year research project on revolutionary intercommunalism within the Third World. I felt an affinity with the collection and enjoyed the privilege of accessing primary evidence firsthand and being able to experience the stories told within, in their rawest and purest form. Initially, the sources that I used were issues of the magazine Jeune Afrique dating from the 1960s and 1970s, which provided me with a valuable insight into the minds of revolutionaries and guerilla fighters (see also chapters by Bethany Collard, and by Tobey Ahamed-Barke, in this volume). It was during this research process that I was approached to help contemporise Tricontinental into a more accessible format for modern-day activists. This article brings together my personal knowledge and lived experience of the trials and tribulations of political activism with the insights of Carlos Marighella’s Minimanual.

The Minimanual of the urban guerilla was not written in a vacuum, so it is essential to understand the historical context surrounding its creation. At the time of its writing Marighella lived under a Brazilian military regime which came to power via a coup d’etat in 1964 (Crandall, 2021, p. 205). The coup was inherently anti-communist; it aimed to depose João Goulart, who was the elected Brazilian president, and, whilst not a actual communist, did have leftwing sympathies (Crandall, 2021, p. 210). After the relatively bloodless coup (Crandall, 2021, p. 213), a regime backed by the United States government assumed power, part of the U.S.’s broader foreign policy objectives to contain communism in Latin America. Whilst the coup was not executed with extreme violence, it led to the gradual repression and eradication of the rights of Brazilians. The repression started with the arresting of peaceful protestors and escalated to imprisonment and extrajudicial killings by government-led death squads, of which Marighella himself was a victim (Dávila, 2013, p. 43). Therefore, this Minimanual was not theoretical; it was a survival guide for many people. I believe that the significance of this publication transcends temporal and spatial specificities, and that the arguments made by Marighella are relevant to anyone who takes part in political action of any kind where the odds and institutions are stacked against you.

The overarching directives concern a guerrilla fighter’s qualities and a revolutionary movement’s organisational structure, which I believe can be transferred to modern-day protest or political action. Whilst democratic systems are qualitatively different to authoritarian dictatorships, in my opinion the immorality of the state still exists. There are countless examples of this in our modern period, from the American War in Vietnam to the illegal invasion of Iraq in 2003. Most recently is the support for the Israeli war machine that has subjected Palestinians in Gaza to crimes against humanity and genocide. Protests, at least in the West and from my personal experience, have fallen on the deaf ears of politicians who play the part of innocent observers whilst simultaneously aiding and abetting these war crimes. What has changed, however, is the sustained political action of millions of people around the world in support of a ceasefire and justice for the Palestinian people.

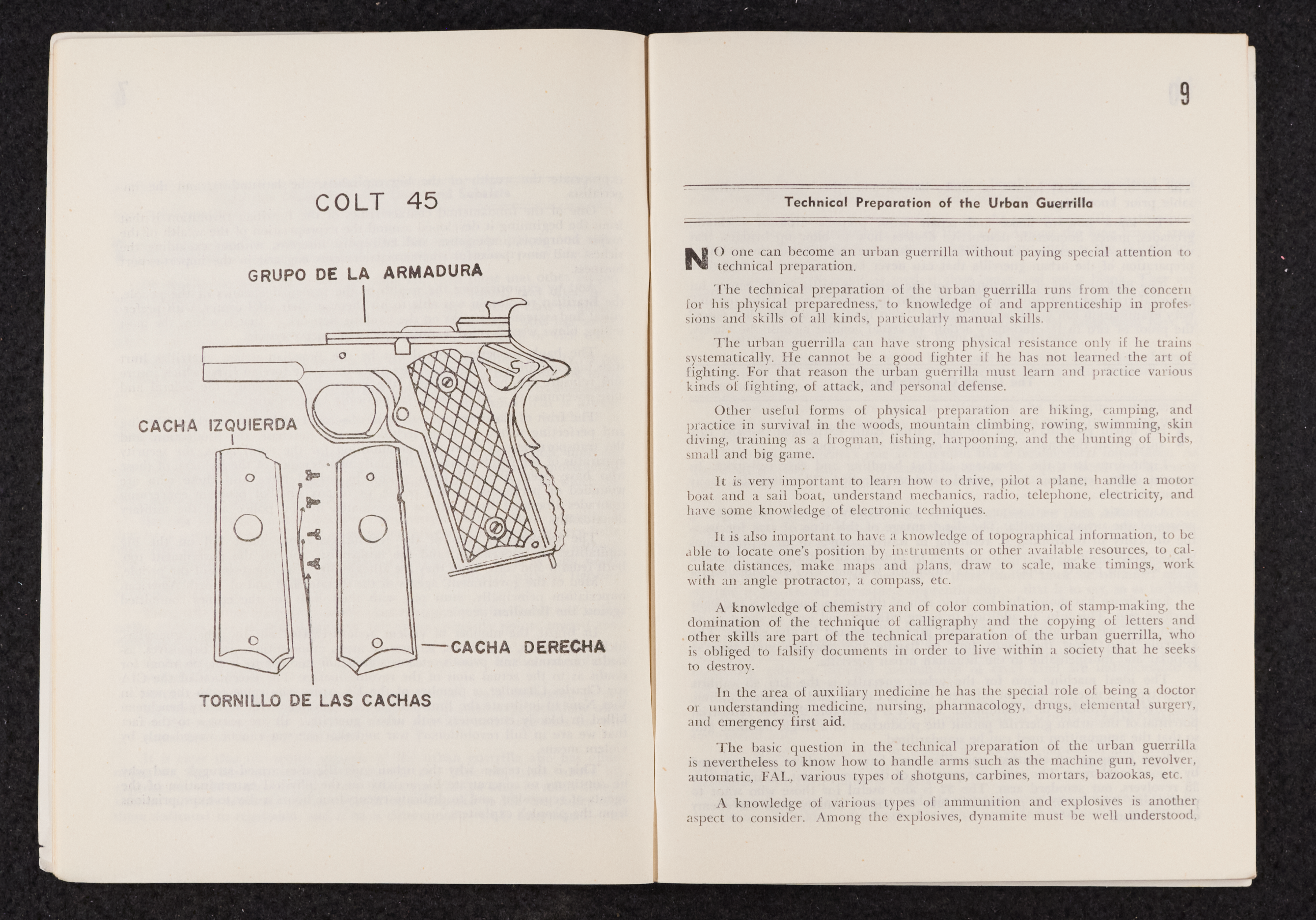

Political action, whether it be putting a sticker calling for the end of Israeli Apartheid on a public toilet door or chanting and marching on the streets of London, is not only an expression of basic human rights but is exhilarating and powerful. It often feels as if your voice, along with thousands of others, should be heard by the state and the immoral politicians who fail to act. What drives this collective assembling of thousands of complex and emotional beings in a single area? It is at least partly the belief that you hold a moral superiority to the state whose actions are immoral. This is what Marighella describes when he writes that ‘the urban guerrilla has undeniable (moral) superiority’ and that ‘the urban guerrilla defends a just cause, which is the people’s cause’ (Marighella, 1970, p. 5).

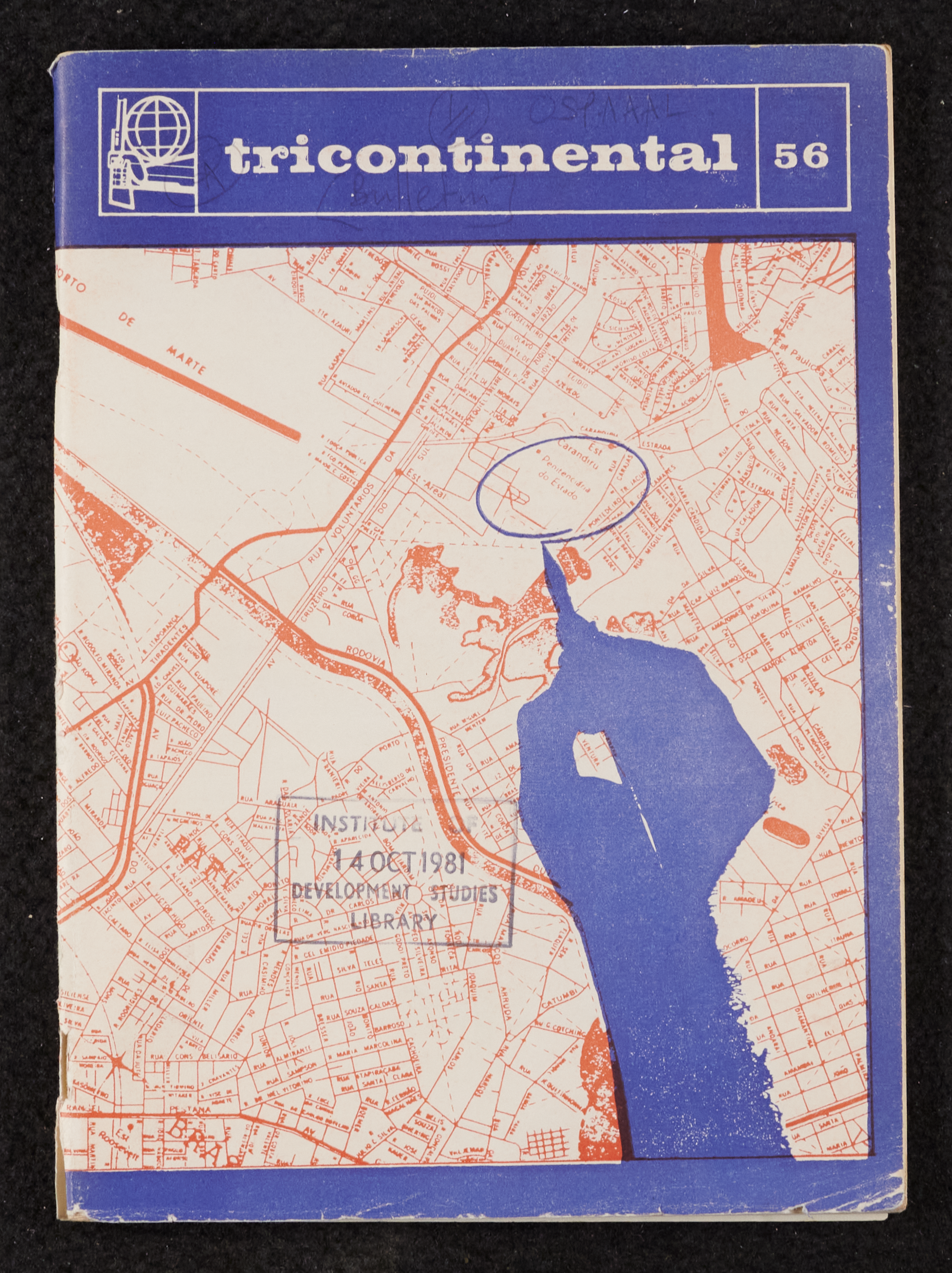

Whilst moral superiority is an excellent foundation for political action, morality alone cannot change an institution’s position. This change needs to be driven by organised and collective action designed to highlight injustice by making it impossible for politicians to ignore the immorality of their (in)actions. Whilst Marighella believed that violent resistance against an oppressive power was righteous and that peaceful protesting is inefficient, one could argue that in a democratic state, political violence is never justified. Instead, the qualities, organisation and potential weaknesses of urban guerrillas (Marighella, 1970, pp. 51-52) can be translated and applied to present-day political action to correct some mistakes made by present and future activists.

Qualities

Where peaceful political activism in democratic nations replaces firearms and explosives, protestors’ qualities become the new tools that drive change. These tools must be practised and implemented to be honed. Marighella outlines five of these tools that we, as protestors, should equip ourselves with: initiative/flexibility, a duty to act, fearlessness, unlimited patience and calmness. Whilst these might seem basic, they are qualities are often overlooked by political activists.

Firstly, initiative/flexibility is an incredibly important skill as plans often fall apart when circumstances change. Having good initiative allows a protestor/activist to think on their feet and take charge of the situation. This kind of free-thinking keeps the targets of your activism on the back foot.

Secondly, a political activist must feel that they have a duty to act – no one can call themselves an activist and not act upon their moral beliefs. This is a problem often found within stationary forms of activism, such as occupations or encampments; they believe that the act of being there is their action. Although this is true to some extent, a stationary form of activism should be a launching pad to escalate further, rather than an end in itself.

Fearlessness. This is a quality that is easier said than done; protesting and standing across from a police or institutional line feels counterintuitive to the norms that we are taught from a very young age. However, with practice and repetition, this feeling of unease dissipates. Standing juxtaposed to a police line with thousands of others fighting for justice against state immorality becomes a collective effervescence.

Finally, patience and calmness are probably the most important features an organiser/planner can possess. Patience is not about waiting or being inactive but instead preparing for the most opportune time to act, often this involves identifying a spark that will unite people. If a protestor possesses calmness, they are an invaluable political organiser. A calm person is usually a sensible person who will not waste their time on angry vendettas nor hold personal grudges against their fellow comrades over personal or ideological disagreements, which is often how political action falls apart.

Overall, these five personal qualities are essential for activism and are often overlooked by activists who can be blinded by ideological beliefs, which can cause damaging schisms within political movements. It is imperative that activists use this guidance to embody these five essential qualities if they truly want to bring about social and political change.

Organisation

The organisational structure of political action is incredibly important, and having a good organisational structure is a do-or-die for most political campaigns. Marighella lays out a series of organisational necessities for guerrilla fighters that I believe can and should be transferred to modern-day political organising.

In the beginning, the planning stage is key, and plans should go from simple to complex rather than the other way around. The reason for this is that often plans with too many moving parts fall apart as they rely on people power, which is a complex and emotional fuel source to run a plan on. Thus, meaning that plans which involve actions of many people simultaneously are likely to break down, whereas a plan in its simplest form can develop into a more complex nature once established that it is practically possible.

Plans are then naturally put into action, and this action must involve a united front of various groups. For instance the student encampment that I was a part of was a broad coalition of peace activists, Marxists, anarchists, socialists and those who felt their morals clashed with the university’s position on Gaza. Whilst initially a united front is easy when emotions are high and people are wanting to act, maintaining it is less easy. It requires many of the aforementioned qualities like calmness and patience with comrades who might disagree with one another. Marighella described a united front as ‘the fruit of fire power in action’ (Marighella, 1970, p. 13); united action allows for not only more types of political action to be enacted but also a sustained bombardment to pressure the state (or university) to agree to your demands.

Finally, as highlighted above, having a multitude of different political actions being undertaken simultaneously is key to a successful campaign. From my own experience, a mixture of large direct action (protests, demonstrations and occupations) intertwined with negotiations with an institution is the best approach.

Seven ‘deadly’ sins

Marighella (1970, pp. 51-52) highlights the seven sins of an urban guerilla, which will be all-too-familiar to activists today:

- Inexperience: In my experience, this can be the biggest disrupter of political action, as activists’ and organisers’ inexperience can often lead them to underestimate institutional power and opposition to their cause. Therefore, pre-emptive celebrations can happen. This can lead to the next sin, vanity.

- Vanity: can appear in multiple different ways, but in the world of protesting, it often manifests itself in the belief that a single action will win a campaign. This can often lead to resources and people power being misspent in a blind effort to have a decisive victory. Instead, the battle should be waged on multiple fronts. An example of this is encampments; they are not the sole solution to defeating a university institution. Therefore, multiple forms of activism are the only solution to sustaining pressure.

- Boasting: is a performative action that is often done by those who wish to assert themselves over other comrades. This sin is especially deadly as loose lips spill secrets and identities. This breaks apart comradely bonds as individuals are seen to move away from the political objective towards their own personal goals. I have experienced this with many comrades, and seen ambitiousness and inexperience dilute their original aims. Interpersonal rivalries and the desire to assert oneself as an impressive activist can cloud rational thought.

- Over-exaggeration: this is not necessarily a malicious or selfish sin. Initially, protests start off with a sense of optimism that you are at the forefront of change and activists can tend to exaggerate the amount of time they can contribute or the resources they have available. This means that plans can be made with resources that are actually unavailable, so realistic expectations are necessary.

- Anger: this is a natural feeling felt by all protestors towards an institution or state, it is what drives people to act. However, once an ordinary citizen becomes a comrade and takes up political action, they cannot and should not act out of anger. Anger tends to obscure rationality and is bad for building a political position on the issue you are campaigning for.

- Precipitous action (hasty or irrational): Acting hastily and without proper consideration of objectives and a plan can lead to the failure of an action. Often this irrational action is tied in with blind anger that can cause mistakes to be made whether it is a miscalculation of the institution’s response or an action that might upset other comrades. Action that is decisive and based out of rational cooperation achieves far more

- Planning: this comes up time and again in the Minimanual and is clearly considered by Marighella to be absolutely key. A plan allows for key considerations to be made, risks to be drawn up and unity to be developed. Improvisation, whilst sometimes necessary, should always be the Plan B that is there in case of emergency. Planning is primary to all political action whether it be from the 1960s or the present day, and it will continue to be the most important thing a revolutionary, urban guerilla or activist can do.

Conclusion

The Minimanual is a perfect example of the relevance of history to the contemporary world. Much of what is written in this issue 56 of Tricontinental is taught by experienced activists to inexperienced activists, and therefore it is clear that this type of knowledge transcends generational boundaries. It also highlights how the mindset needed for activism has not changed, nor have the organisational structures that make a successful radical political action – the tenets outlined by Marighella are just as relevant today

Whilst this essay has only explored one issue of Tricontinental, the entire collection is filled with insights into the minds of Third World leaders such as Kim Il-Sung and Ho Chi Minh as well as from other less well-known revolutionaries. Reading primary sources is always a joy for students and academics alike, and the Tricontinentals are especially exciting to read as they are truly revolutionary, with each page firing a bullet at imperialism. Whilst many of the revolutions in the pages have ended decades ago, the echo of this gunfire still resonates, showing how what could be considered a historical artefact is actually a living and breathing guide to our generation in its struggle for a better world.

References

Crandall, B. H., & Crandall, R. C. (2021). “Our Hemisphere”?: The United States in Latin America, from 1776 to the twenty-first century. Yale University Press London.