7 Sights, sounds and smells of revolutionary paper: Exploring Tricontinental as a collection of primary sources

Danny Millum

Until then I had thought each book spoke of the things, human or divine, that lie outside books. Now I realized that not infrequently books speak of books: it is as if they spoke among themselves. In the light of this reflection, the library seemed all the more disturbing to me. (Umberto Eco, Name of the Rose)

In the preceding chapters we have looked at the British Library for Development Studies (BLDS) Legacy Collection, Tricontinental, OSPAAAL itself, and publishing houses more generally.

The following sections will lay out some different methodological and practical approaches to such materials.

What I would like to do in my short piece here is to talk a little bit about the importance of the ideas of collections and primary sources, again using Tricontinental as a focus but continuing to be clear that this is just an example – that these ideas can also be applied to other sources and collections.

In addition, I will be stressing the importance of reading across a collection, not just internally within a document, and illustrating this with reference to the BLDS Legacy Collection itself.

Let’s begin (with apologies to both archivists and librarians) by quickly distinguishing between archives and special collections.

Archives are generally defined as a collection of documents or records, often historical, providing information about an individual, place, institution, corporation, organisation, or group of people, and selected for permanent preservation. Special collections refer to any cohesive collection of research materials linked by origin or by a thematic focus [https://dictionary.archivists.org]. These often include archives, but also incorporate selected collections of published material as well.

It’s clear then that the BLDS Legacy Collection falls into the latter category – material collected by IDS Librarians linked largely by thematic focus, namely its relevance to the study of development.

By the very fact of its location as part of the BLDS Legacy Collection at Sussex, Tricontinental takes on additional meaning and resonance. Various runs of the journal exist in different repositories across the world, but each of them will be understood differently by users for a variety of reasons.

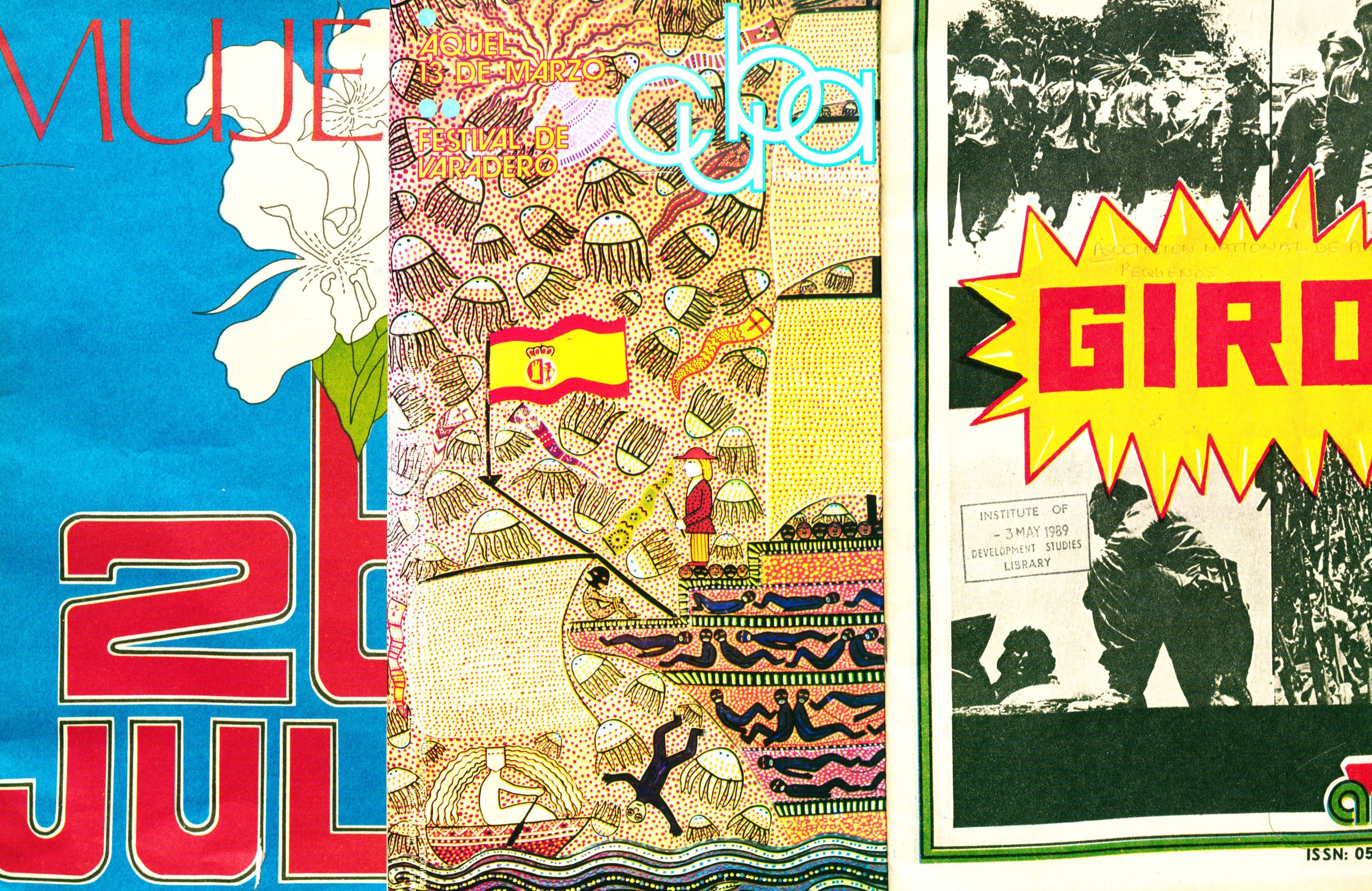

For instance, those who come to read Tricontinental in the Library at Sussex will find it nestled within a collection of a quarter of a million other Global South items – it is not an outlier (as would be the case were it located within a normal university library politics classmark) but more an exemplar of the type of material that surrounds it, which includes other Cuban journals such as the Asociacion Nacional de Agricultores Pequenos, Cuadernos de Nuestra America, Cuba Internacional, Economia y Desarrollo, Mujeres, and Revista Mensual.

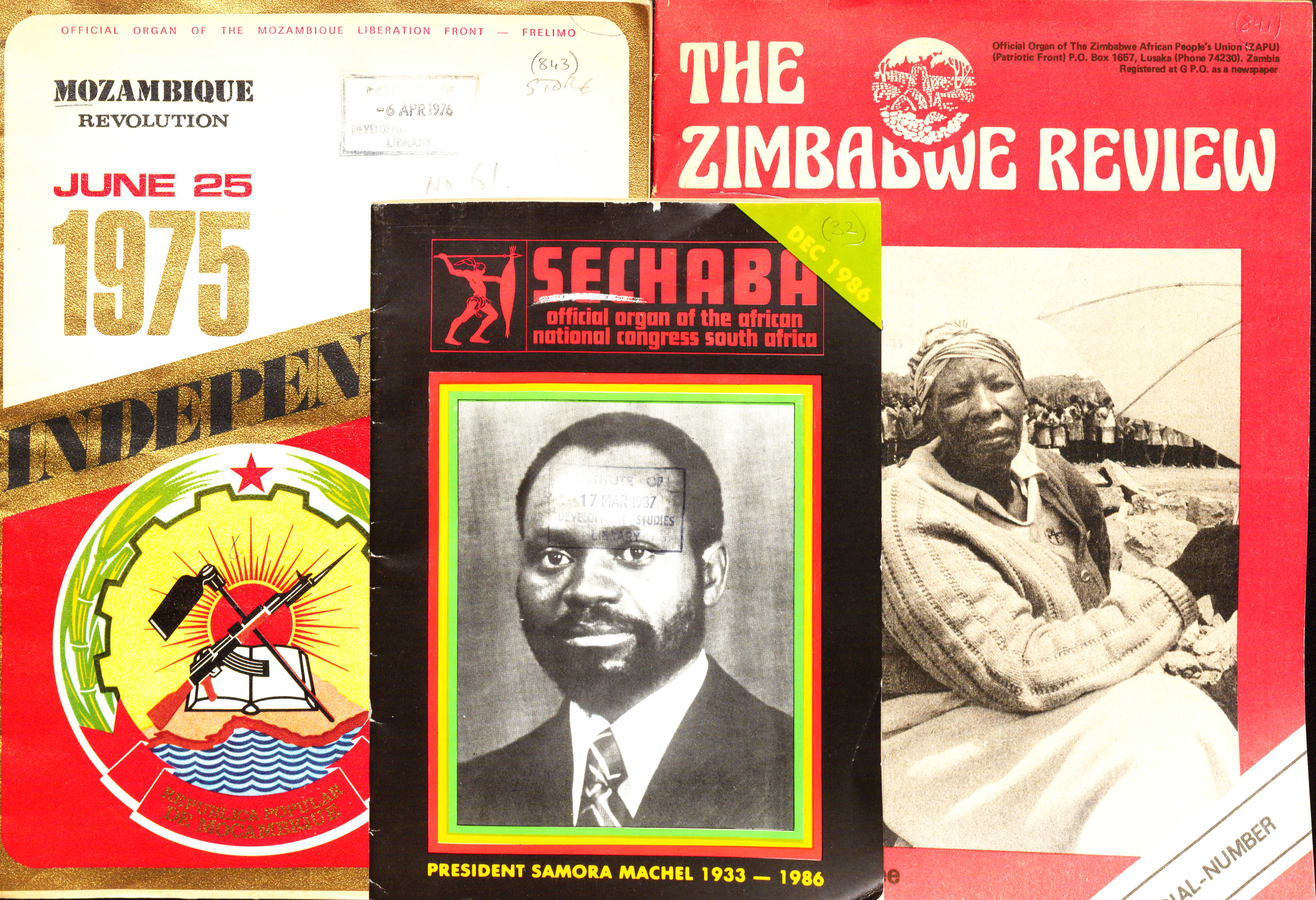

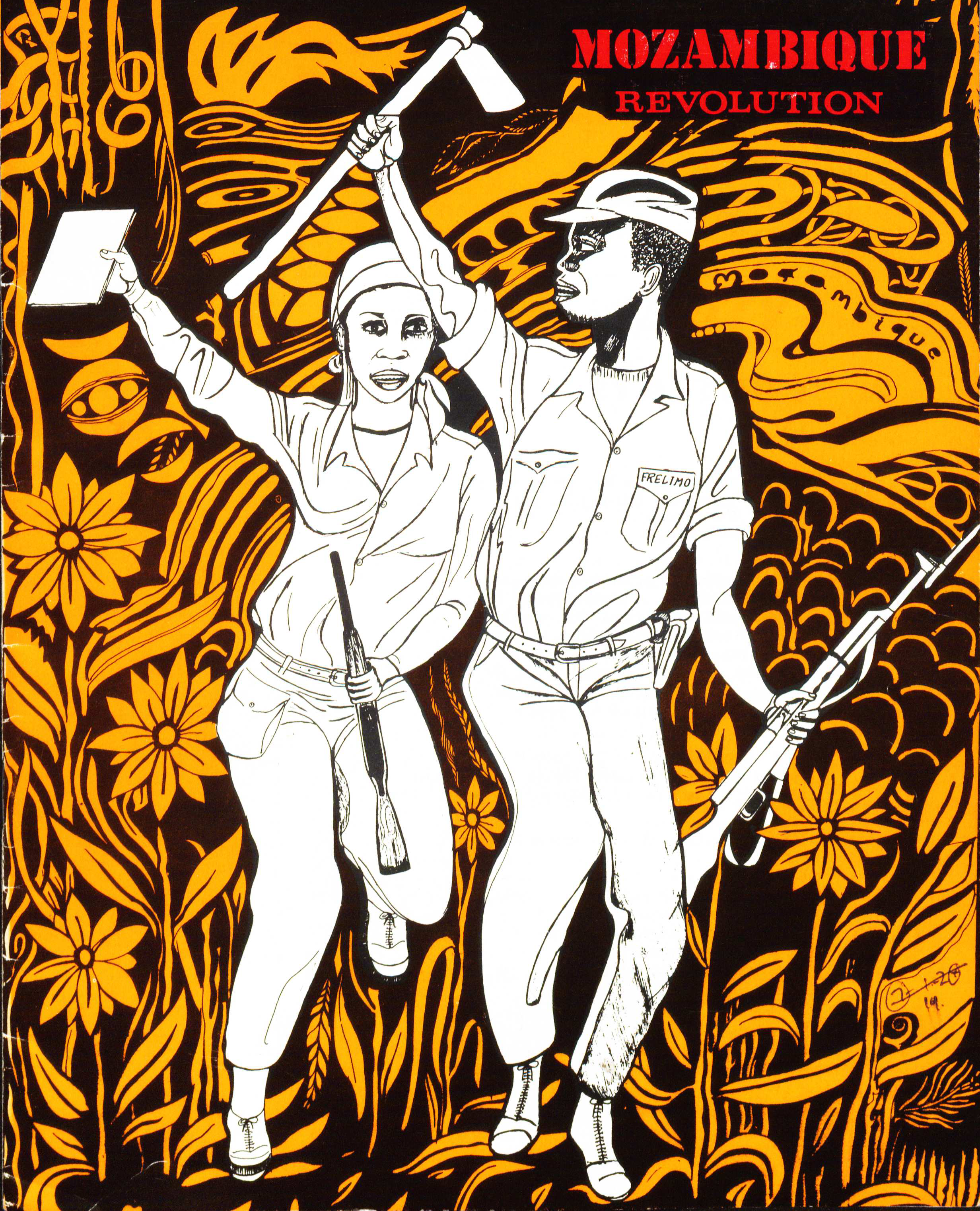

As can be seen in the accompanying chapters, the collection also includes a host of other anti-colonial/ anti-imperialist journals from other countries – many of which describe liberation struggles also covered by Tricontinental (see for instance the holdings of materials produced by the Frente de Libertação de Moçambique (FRELIMO), the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU) and the African National Congress (ANC).

As Eco suggests, collections can engage all of our senses – including smell. I remember walking into the BLDS Legacy basement on the day of my interview at Sussex, and being transported Proustian-style back 20 years to my first job in London cataloguing a similar collection of Commonwealth ephemera. [Editor’s note – we would make an exception for the sense of taste, as we tend to discourage readers from licking the materials].

One cannot separate out the analysis and writing of history from the process of research in the fashion implied in positivist social science. (Lipartito, p.288)

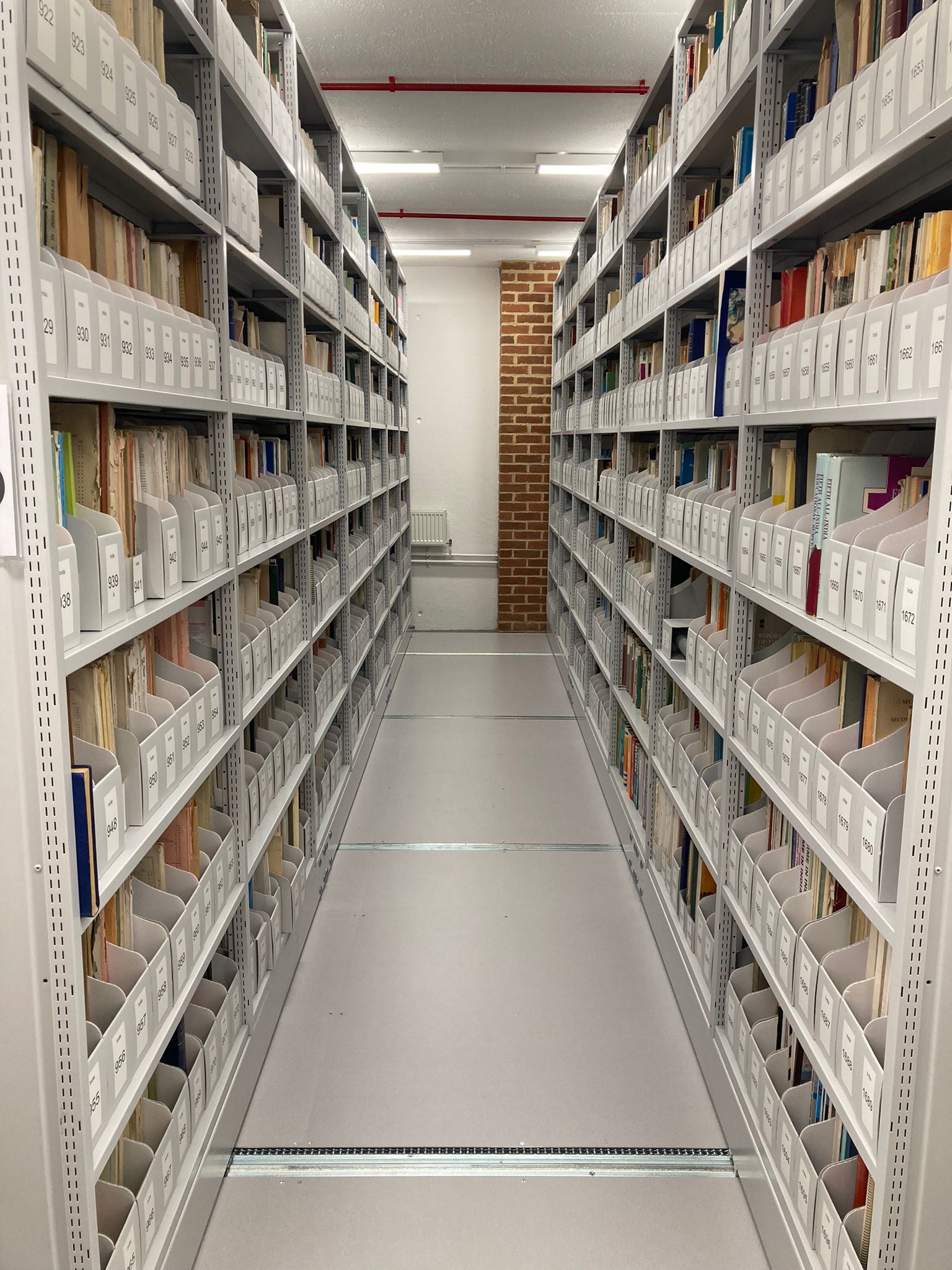

It’s therefore not possible for the digitisation described in the chapter by Karen Smith (while it unlocks a whole host of other possibilities) to afford the same experience for any researcher as a visit to the University of Sussex Library collections. The BLDS Legacy Collection fills an entire basement, and it’s become a staple of our collections teaching sessions to take students into the stacks and give them a sense of scale and cohesiveness.

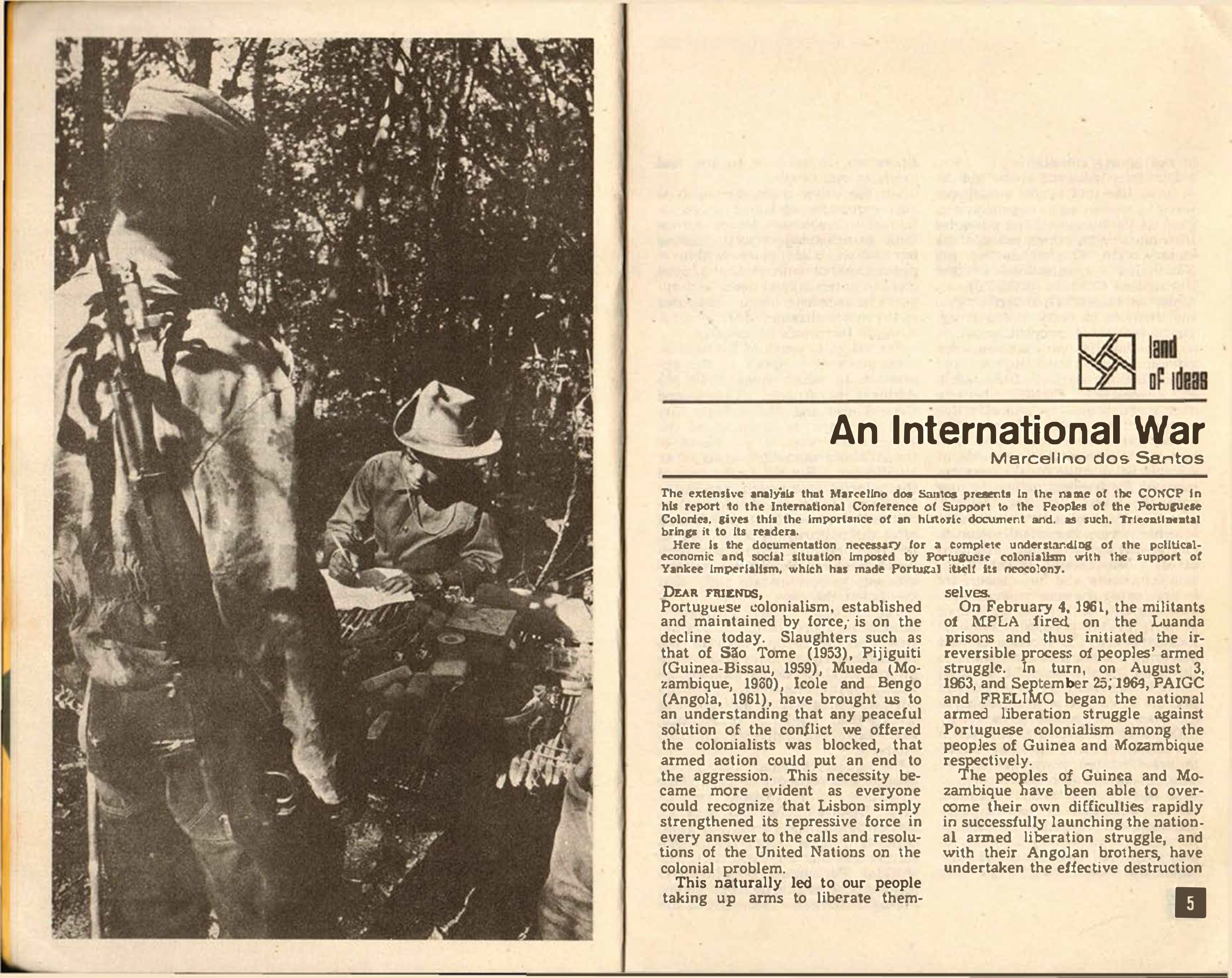

Here alone is it possible to experience Tricontinental in this particular mix (and obviously other, even more potent, combinations will be available elsewhere). The researcher can move (almost) seamlessly from the discussion in Tricontinental 23 by Marcelino dos Santos of ‘An International War – extensive analysis of the political, economic and social situation imposed by Portuguese colonialism with the support of Yankee imperialism’ to leafing through the pages of FRELIMO’s Mozambique Revolution or The Combatant from Angola.

One starts to see not just ‘letters to the editors and responses, position pieces and replies, minutes taken at various meetings, reports on negotiations, or critiques within various movement splinters. These are the dynamic conversations that are recorded within periodicals’ (Shamshiri, 2024) within individual periodicals but also across them.

This cross-pollination combined with the materiality of the publications leads one next to ponder their physical journey to the collection – as Alice Corble notes elsewhere in this volume, early Tricontinentals took up to 16 years to arrive at Sussex – where had they been in the meantime? And what collecting decisions led to them arriving when they did? These are often hard to uncover but key to bear in mind for any researcher noting annotations, library accession stamps or torn-out subscription pages. This also comes with a health warning from a librarian – we do sometimes trample all over the crime scene, filling gaps in a run of journals without footnoting the fact and leading to all manner of erroneous conclusions for the historians of collections to retrospectively draw.

The attentive reader will see that we’ve already slipped from macro to micro, from the bird’s eye view of the collections as a whole to a discussion of the aspects of individual primary sources – and so it’s worth briefly dwelling on the nature and importance of the latter before applying these thoughts to the Tricontinentals.

What are primary sources?

Primary sources are the raw materials of history— original documents and objects which were created at the time under study. They are different from secondary sources, accounts or interpretations of events created by someone without firsthand experience. (Newman, 2014, p. 10, quoting from Library of Congress)

Primary sources are firsthand, direct evidence. The key words are firsthand and direct. They imply being there, having a direct connection to a person, event, or place. But being there can have varied meanings. (Newman, 2014, p. 10)

Now wait, I hear you say! Surely a journal article is a classic example of a secondary source? These are not firsthand eyewitness accounts! What are you going to claim next – that this book that you are reading now is a primary source as well? Where will this all end?

Good questions. To which the reply could be another question – why can’t an artefact be both primary and secondary? If we’re looking at the history of the Vietnam War, then Tricontinental is a secondary source drawing on other primary sources to provide an interpretation of that history. But if we are interested in the history of revolutionary interventions in the anti-imperialist struggle, then Tricontinental is a prime and primary example of this – and it is as such that we will be considering it.

Primary sources are complex mixture of insights and pitfalls – offering the opportunity to experience the past un-(or at least less-)mediated by hindsight but on the flipside without the clarity that historical perspective can bring.

Let’s try and elaborate on these thoughts a little by looking at some concrete examples from the collection.

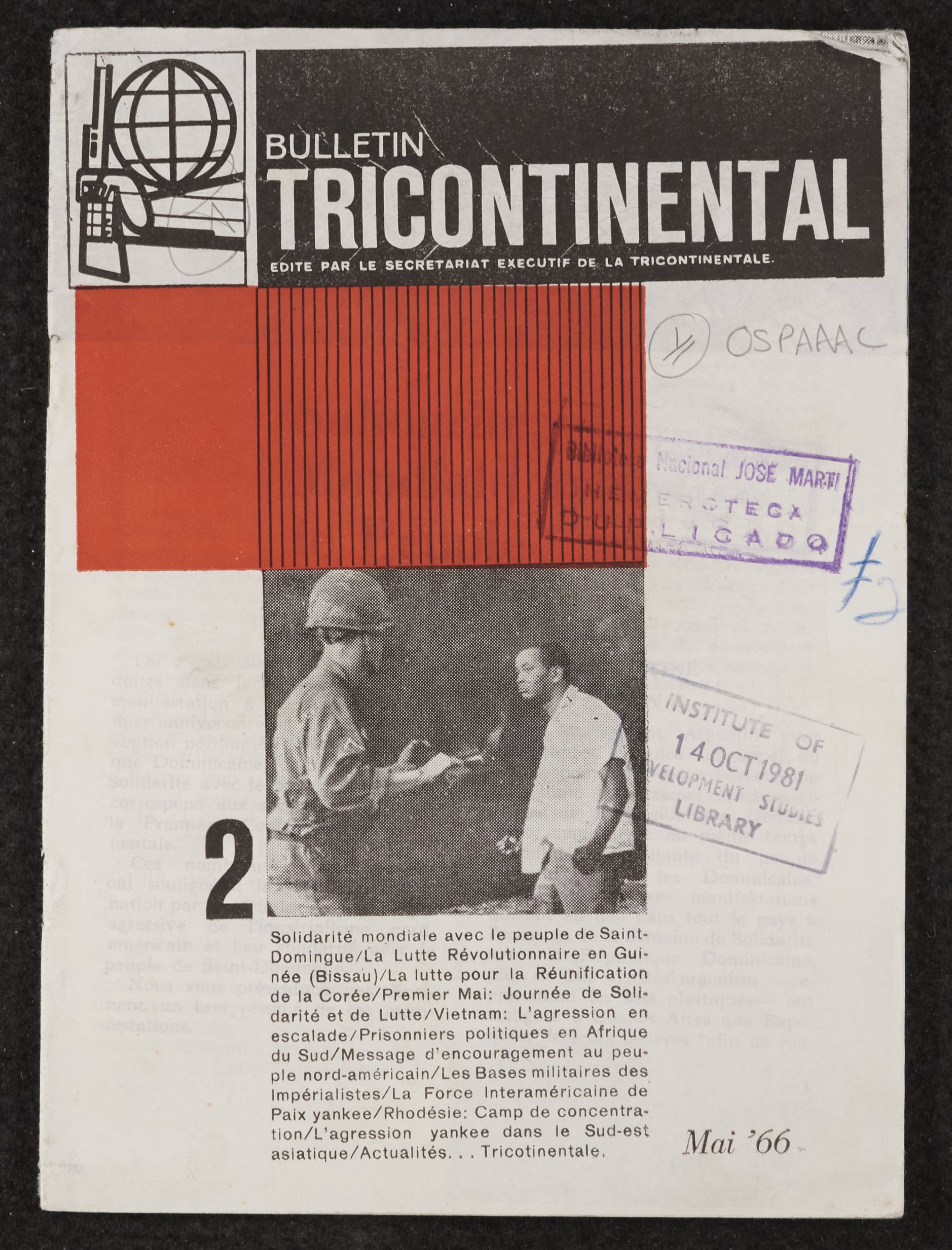

Here’s Issue 2 of the Tricontinental Bulletin:

Even the process of identification is not as straightforward as it seems, however – while the cover reads ‘2’, it is actually the third Bulletin – for no apparent reason, there are actually two number 1s.

I have the copy in front of me now, and it’s such a lovely example of how different it is to handle the actual material item compared to a digital scan, let alone a sourcebook from 60 years later telling you about it.

The paper is super thin, and one senses the possibility of damage even opening up the issue carefully. There are clear signs of use – the ink is smudged and the top right hand corner of the pages is curled back.

All manner of annotations attend the first page, most notably:

- A stamp from the Biblioteca Nacional Jose Marti, reading ‘BIBLIOTECA DUPLICADO’

- A stamp from the Institute of Development Studies Library dated ’14 Oct 1981’

- Two blue crayon symbols

- Pencil marks indicating the IDS filing arrangement (1// OSPAAAL (A) TRICONTINENTAL)

Already here we can both chart the journey of this item and start to require additional information to resolve the further questions that these annotations throw up. It turns out that rather than there being a 16-year postal lag between the dispatch of a duplicate from Havana and its arrival in Brighton, every single issue in the initial run is stamped 14 Oct 1981, suggesting the arrival of a job lot at IDS rather than an initial subscription.

This immediately confuses our picture of the original reader – rather than being consumed (almost) contemporaneously by researchers and students at the IDS in the 1960s and 1970s, and feeding into the Institute’s ongoing debates and approaches, Tricontinental didn’t even arrive until the 1980s! Another potential pitfall to be negotiated…

Beyond the purely physical, we have the design and the contents to look at. I don’t want to dwell overly on the Tricontinental aesthetic, as Alexandra Lewis has written at length on this in a chapter for this volume, but I will say that it does constitute another argument both for looking at the materials in person, to learn more from the exposure and fading of certain colour palettes, and also a justification for digitisation, to allow these amazing images to be zoomed in on and studied in detail.

Moving though to the contents themselves, the first thing I’d like to pick up on is the issue of language. This is especially interesting with regard to international publications of this sort, produced in a multilingual format and where it is difficult for the reader to have absolute certainty as to the process of translation. Are the Spanish and English versions simply duplicates, or are there also substantial changes? Let’s try and find out!

There are obviously two ways of doing this. One would be to research into the history of the journal for accounts of its practical operation – either through looking at OSPAAAL’s archives (very hard) or reading secondary accounts (easier, but less authoritative and less fun). The other is to look at the materials themselves, and as we’re concerned in this chapter with the use of primary sources that’s the approach we’re going to take!

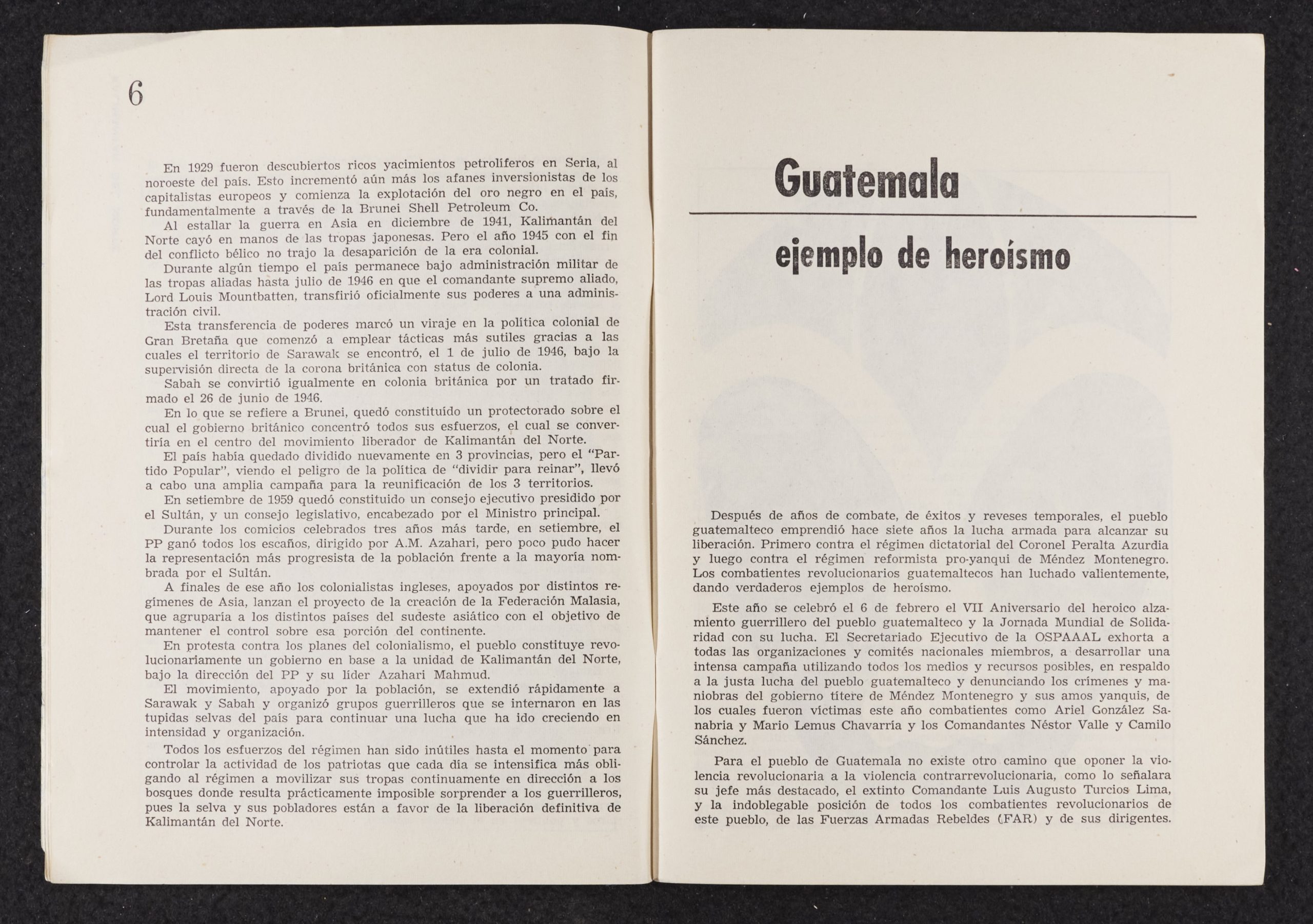

In order to do so, the first task is to identify issues where the holdings in both languages can be accessed. I’ve chosen issue 35 of the Tricontinental Bulletin, held in English in the Freedom Archives and in Spanish at the University of Sussex.

Looking first at the bulletin, it seems clear (and would be logical) that the Spanish version is the ‘master copy’. This can be partly deduced from the higher quality and more consistent typeface and layout deployed, but (I believe) also from an analysis of the use of the language.

A good example of this is on page 7, in an article about Guatemala. The last line of the Spanish version reads:

‘Los combatientes revolucionarios guatemaltecos han luchado valientemente, dando verdaderos ejemplos de heroísmo.’

In the English version we have:

‘The Guatemalan revolutionary combatants have bravely fought, setting examples of true heroism.’

I think we can learn a lot from just this one comparison. It’s clearly a verbatim translation – rather than a different version written by an English speaker, for instance. But also it’s clear it’s a translation which is going from Spanish to English – the Spanish is smooth and idiomatic, while the English is perfectly comprehensible but not that of a native speaker composing an original sentence.

Another more subtle piece of evidence that this mode of verbatim translation has been used is the density of the two languages. English is notably more dense than Spanish and as a consequence one would normally expect an English magazine to be 20-30% less pages than a Spanish one. The Tricontinental layout doesn’t allow for this though, and so a more word-for-word translation is also likely to pad out the English and hence ensure the pages line up properly.

Please note – this is clearly conjecture based on a single line of a single issue! We’re not trying to prove the point unequivocally here BUT rather illustrate yet another rabbit-hole that in-depth analysis of a primary source can take us down.

Let’s have a look at the text now. There are infinite insights that can be gleaned from a primary source such as this, but we’ll just try and illustrate one vital aspect of primary sources just to get you started!

What I always like to talk about when teaching students is the idea of contingency – that primary sources show us how actors in the middle of history – who for instance don’t know [SPOILER ALERT] that apartheid actually ends – thought at the time, without hindsight.

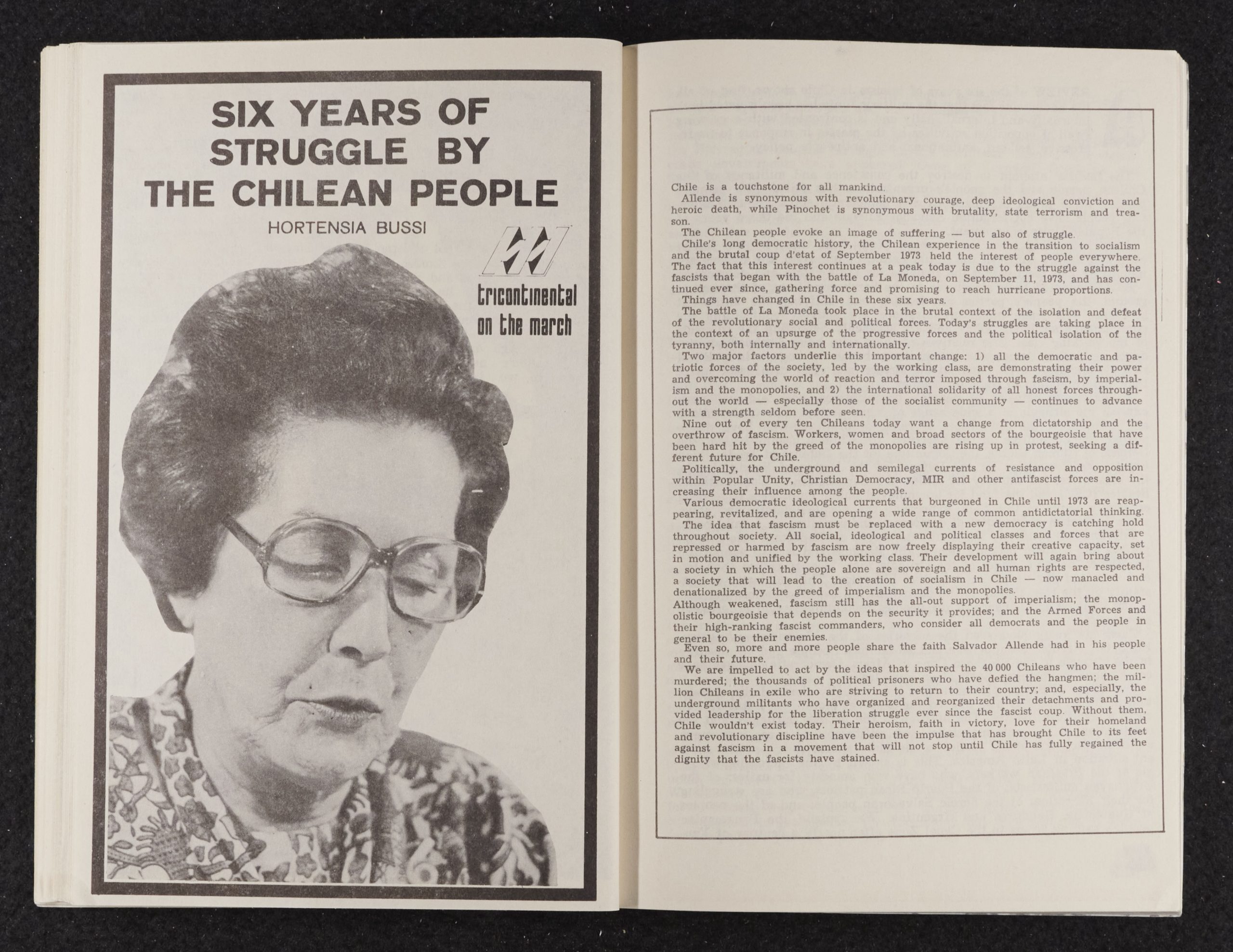

Why is this interesting? Let’s demonstrate using issue 67/68 of the Tricontinental Magazine from 1980, and the article ‘Six Years of Struggle by the Chilean People’ by Hortensia Bussi.

With hindsight, this is not a significant date in Chilean history. Following the 1973 coup against Allende, the brutal Pinochet dictatorship would last until 1989, and so has almost another decade to run. But you would never guess that from the article, which is a comprehensive summary of all of the ways in which resistance to the regime is building, starting with the claim that ‘Today’s struggles are taking place in the context of an upsurge of the progressive forces and the political isolation of the tyranny, both internally and internationally’ (p. 71) and ending with the conclusion that ‘the people are ready to defy the repression in order to win their rights again’ (p. 84).

For the author, the end of the dictatorship is potentially imminent, and could come at any moment. There is therefore a pathos for us, the audience reading this article many years later, in knowing what the author does not – that another nine years will elapse before Pinochet is finally deposed. There is a kind of contradiction here – in one way we are distanced from the primary source (compared to a secondary source where we share the advantage of hindsight) but in another way we are brought closer, in that we experience the world of 1980 as it actually appeared to those living through it.

In fact, if we zoom out from Chile to the world situation as depicted by Tricontinental in early 1980, we see an even greater disjuncture with hindsight. This very same article states with confidence: ‘the international solidarity of all honest forces throughout the world — especially those of the socialist community — continues to advance with a strength seldom before seen’ (p. 71).

It’s easy to dismiss this as propaganda or wishful thinking, but fascinating to take it at face value, and consider that at just the moment when the Thatcher/Reagan era was beginning, the point any textbook would consider marking a defining turn to the right and neo-liberalism, Tricontinental saw the prospects of world revolution as being closer than ever.

Besides the author, we have the reader – another consciousness that the primary source encourages us to empathise with. We can distinguish here between different types of reader. We have our library user alluded to above, finally receiving Tricontinental 16 years after the fact and seeing it very much as we do. But we can get a sense of another, more immediate reader from the letters pages which were a feature of early issues of the Bulletin.

Many of these letters are semi-formal in tone and addressed from aligned political organisations from both Global North and South. But there are fascinating glimpses of more personalised correspondence. Who, for instance, is Daniel MacReady, who writes without organisation or address (Tricontinental Bulletin, No. 30, p. 46) that ‘we have so little opportunity in this country of learnig [sic] anything about Viet-Nam except what the Criminal and his cronies in the White House want us to hear’? What lies behind Desmond Brenan, chair of the University Catholic Society of New Zealand, and his corrective letter (Tricontinental Bulletin, No. 32, p. 39) stating that ‘we can not endorse the personal views of our National Secretary expressed in the letter to you’? These are just further threads that these sources entice us to follow…

One final example before we have to tear ourselves away comes from reading not the substantive content of the journal, but rather the mechanics of its subscription process. On page 120 of Issue 33 of the Tricontinental Magazine we find a subscription coupon to be torn out, completed and mailed back along with a cheque for $3.60 to PO Box 4224, Havana, Cuba. To eyes jaundiced by a world of online subscription models this looks like an impossible leap of faith – and yet one which 100,000 subscribers made during the heyday of Tricontinental.

As we announced at the start, this chapter is intended to be the opposite of comprehensive – but rather to whet the appetite for exploring resources such as Tricontinental through their nature as collections of primary sources. As such it seems completely appropriate to conclude abruptly with some unanswered questions which might prompt your first turnings into your own maze:

- Who collected these materials, and why?

- How did they do it? Were they collected at the time or donated later?

- How do they fit into the rest of the collections?

- Who was reading them? And where? And when?

- How do they look? Feel? Sound? Smell?

- What paper are they written on? Is it worn? Untouched?

- Are there marks/annotations/graffiti/pages torn out?

- What languages are used?

- What were the authors trying to achieve? Scholarly communication? Or world revolution?

References

Shamshiri, M. (2024). ‘Periodicals were the beating hearts of global movements’: An interview with Mahvish Ahmad, Koni Benson, and Hana Morgenstern of Revolutionary Papers. Wasafiri, 39(2), 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/02690055.2024.2315775

Newman, M. (2014).Vital witnesses : Using primary sources in History and Social Studies. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Incorporated.

Nunes, C., & Gustavson, A. (2023). Transforming the authority of the archive: Undergraduate pedagogy and critical digital archives. Lever Press. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/book.114487.

Lipartito, K. (2014). Historical sources and data. In M. Bucheli and R. D. Wadhwani (Eds.) Organizations in time: History, theory, methods (pp. 284-304). Oxford University Press.

Donnelly, M., & Norton, C. (2020). Doing History (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003107781