16 Tricontinental and the psychology of colonialism in Lebanon

Iman Makdisi

Tricontinental, the journal founded by the Organisation of Solidarity with the People of Asia, Africa, and Latin America (OSPAAAL), serves as a powerful reminder of both the dominance of Western colonialism and the solidarity among people in the Global South in their anti-colonial struggles; an enduring symbol of resistance and hope for a more just world.

While occupiers and colonisers tend to write the dominant narrative of history, Tricontinental presents a written testament through the lens of the occupied and colonised, offering an alternative account of events from the view of those most impacted by imperialism. I began reading the journal with a curiosity about how the colonial past was recorded when it was still the present and comparing it to how current colonial dynamics are being written about today. Looking through the archives, it’s clear that history repeats itself in both disappointing and encouraging ways.

It was in this context that I sought to use through Tricontinental to learn more about Lebanon, my home, and the struggle of its people during the French mandate, post-colonial reality, and the successive Israeli invasions that still occur to this day. As a psychology student, I was particularly interested in the psychological aspect of these events. There is a contradictory interplay between the persistent colonial mentality in Lebanon (in relation to both France, and, in a different way, to Israel) and the anti-colonial mentality of resistance against both the sectarian political project and occupation. Leafing through the collection, I found several pieces written in Tricontinental that I drew from to understand and analyse these opposing mentalities in Lebanon. The material I discovered includes interpretations of Frantz Fanon’s ideas, which remain relevant to understanding psychoanalysis in the context of colonialism, an approach which is arguably undertaught in today’s psychology classes. (Makdisi, Makdisi, & Makdisi, 2025). Alongside Fanon’s analysis, several Tricontinental magazine issues highlight the parallels between the internal displacement and destruction that Lebanon has faced since the late 1970s, and have particular contemporary resonance given the continued Lebanese condition of division and war. Moreover, repeated Israeli invasions in Lebanon have created another layer of mental distress and unresolved generational trauma that can be observed throughout this period.

In January 2025, after Israel’s brutal two-month war on Lebanon, I visited a family friend’s destroyed home in the heavily targeted south. A month later, I was strongly reminded of this visit while looking through the various Tricontinental issues that illustrated the different Israeli invasions in Lebanon through photographs and descriptions. For example, the 67th issue (1980) of Tricontinental published an interview with George Haoui, the General Secretary of the Lebanese Communist Party (LCP) at the time (OSPAAAL, 1980, pp.60-61).

The LCP was part of the larger Lebanese National Movement, which was pushing for a more secular system in Lebanon during the 1970s. Haoui describes the situation in the south much like it might be described today, as he recounts the increasing Israeli aggression, evacuations, and casualties of hundreds of people in civilian areas, as well as attacks on villages and Palestinian refugee camps.

Another example of Tricontinental’s coverage of this conflict can be found in the 110th issue (1978), written in French, where Irma Caceres (1978), a Cuban journalist, depicts her visit to the south of Lebanon in a piece titled ‘Une ville fantôme’, or, translated, ‘A ghost city’. Caceres, a self-described impartial observer, illustrates the catastrophic levels of destruction she witnessed in the south and the intense emotion she experienced. The parallels between Caceres’ descriptions, and what I saw just two months previous to reading her piece, are striking. She speaks of her route from Beirut to Saida and their famous citrus orchards; from Saida to Tyre, and the gradual decline in the number of cars making their journey south. She describes a once-vibrant city turned ghost town and the precious archaeologic lands turned into the poorest of quarters. In both Haoui’s interview and Caceres’ recounts, pictures of the destruction were included in the published articles to illustrate the civilian homes targeted, a cruel violation of international law. The parallels between issues written in 1978 and 1980, and the present day, are uncanny.

The people in south Lebanon have had to endure what seem to be never-ending waves of internal displacement as part of the broader Israeli aims of occupation and territorial expansion. While one cannot understate the physical damage and pain caused, the psychological warfare that the Israeli military uses regularly to inflict harm on its victims is a well-known tactic. For instance, the sonic booms made by Israeli warplanes breaking the sound barrier or the incessant buzz of the low-flying drones that instil constant fear over people on the ground. These strategies are still being implemented today and are ones that I am familiar with. In the last two years, additional inhumane strategies have been used to evoke suffering. For example, the recent 2024 pager bombings targeted thousands, including civilians, in their homes, their workplaces, and with their families. The unlawful violation of Lebanon and damage to its people has produced deeply rooted intergenerational trauma and a national mental health crisis. Not only does this directly affect the population living there, it also traumatises those living outside and watching their families from afar – a survivor’s guilt that is arguably worse.

Along with his description of the south, Haoui provides historical context for the current political and socioeconomic situation in Lebanon. He explains the impact of French colonialism on the Lebanese superstructure, forcing internal religious divides onto a country with a history of peaceful coexistence between the 18 officially recognised religious sects inhabiting it. When questioned, Haoui clarifies that the major problem in Lebanon is not religion (although it has partially manifested into this), but rather the class divide. He explains the influence of the French mandate and its manufactured insertion of Maronite Christian political power as one primary reason for this division. Even today, this is evident both at the official level, where the President, Governor of the Central Bank, and Head of Army are traditionally Maronite Christian, and at a social level, with the Christian bourgeoise having dominated the economic sphere. These divisions work in tandem with Lebanon’s culture of coexistence to create a politically sectarian and yet socially secular society.

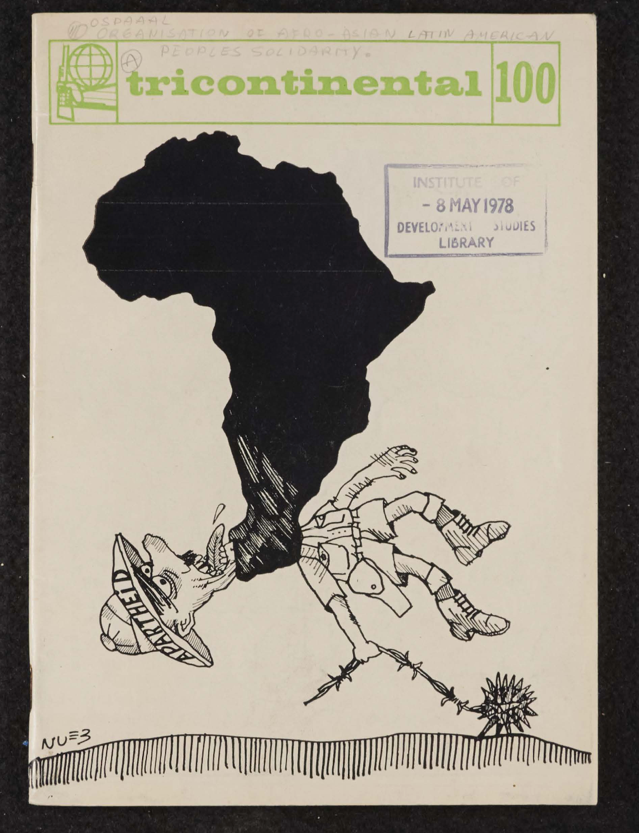

However, the post-colonial psychological mentality remains split in Lebanon. Some reminisce about the past (typically the bourgeoise and elite), even having a nostalgia for French control; others ground themselves in the Lebanese national identity or pan-Arab identity, and have a strong dislike for the French and their involvement. An example of the former reaction is the response after the 2020 August explosion in Beirut’s port that left over 300,000 people in the capital city displaced. I remember being there, watching the news of French President Emmanuel Macron’s visit to Gemmayze, a Christian neighbourhood in Beirut, where his show of support reflected a patriarchal and colonial protector complex. Soon after, a petition with nearly 60,000 signatures emerged demanding a return for the French mandate. Although this was not serious in political terms, it did show how some were stuck in a colonial past. This psychological state can be explained by Fanon’s work, which Jaques Bonaldi refers to in his article ‘A cauldron under pressure’ in the 100th issue of Tricontinental from 1976 (Bonaldi, 1976).

Bonaldi uses Fanon’s ideas to explain the psychological colonial structure of apartheid South Africa at the time. He quotes a passage from Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth to explain the mental impact of colonialism. Fanon says that the way in which a coloniser not only physically inserts themselves in the land of the natives, but also psychologically manipulates the narrative, follows a Manichean worldview. The Manichean philosophy claims that the indigenous population embodies evil while the coloniser is a gift sent to liberate them from evil. This narrative of good versus evil, which is used to justify the imposed colonial hierarchy, lays the foundations for racism and fosters the psychological, political, and social dynamic between the settlers and the local population. Despite the very different circumstances, Bonaldi’s interpretation of Fanon’s psychoanalysis in South Africa can be used to situate the social dynamic in Lebanon with its history of the French mandate.

To conclude, these examples show how Tricontinental can be read through a psychological lens to shed light on Lebanon both past and present. The socio-economic and political situation that Haoui conveys is undeniably complex, as it bears the consequences of a post-colonial reality on one hand, and a relentless external threat of occupation and violence on the other. In addition, the various psychological realities produced by Lebanon’s recent history and ongoing resistance to occupation in the south can be understood through the framework of Fanon’s psychoanalysis of colonial trauma. Reading about Lebanon in the 1970s and 1980s in the Tricontinental collection gave me a clearer understanding of what my parents, grandparents, and great grandparents experienced, while also revealing how little has changed since then. It is important to recognise the psychological repercussions of this cyclical history, in both Western dominance and anti-colonial resistance.

References

Caceres, I. (1978). ‘Une ville fantome’. Tricontinental 110.

Bonaldi, J-F. (1976). ‘A cauldron under pressure’. Tricontinental 100, 2-10.

Makdisi, K., Makdisi, D., & Makdisi, U. (2025, March 11). ‘Nobody wants to name the traumatizer’ w/ Lara Sheehi. (Podcast). Makdisi Street. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zL3mhQMDvZo