2 Tricontinental territories of anticolonial knowledge production and liberatory library learning

Alice Corble

Introduction

Over the past decade, catalysed by the 2015 #FeesMustFall and #RhodesMustFall student-led movements in South Africa, campaigns to ‘decolonise’ higher education (HE) have spread globally (Adefila et al., 2022; Bhambra et al., 2018; Chantiluke et al., 2018; Chigudu, 2020). These movements critique Eurocentric curricula and structural racism perpetuating epistemic violence (Carr et al., 2023; Mbembe, 2016). Practice-based efforts towards academic decolonial reform include incorporating anti-colonial pedagogies and perspectives into teaching and research (Arday et al., 2021; Hlatshwayo, 2021; Phipps & McDonnell, 2021). However, many maintain that these efforts are weakened without organising to transform the neoliberal global forces that sustain colonial inequality (Enslin & Hedge, 2024; Heleta, 2023). Such organising must be grounded in the material histories of anti-imperial liberation movements that reshaped global landscapes of development and knowledge in the 20th century (Choudry & Vally, 2020).

Academic libraries play a central yet often overlooked role in these struggles; without them universities and global systems of knowledge production would cease to function or develop effectively. My research focuses on pivotal role of library and archival practices in both reinforcing and resisting colonial conditions of knowledge production and learning. As gatekeepers, organisers, mediators, and midwives of information, knowledge and institutional memory, librarians and archivists are key collaborators in shaping HE’s liberatory potential (Caswell, 2021; Crilly & Everitt, 2021; Keith et al., 2024).

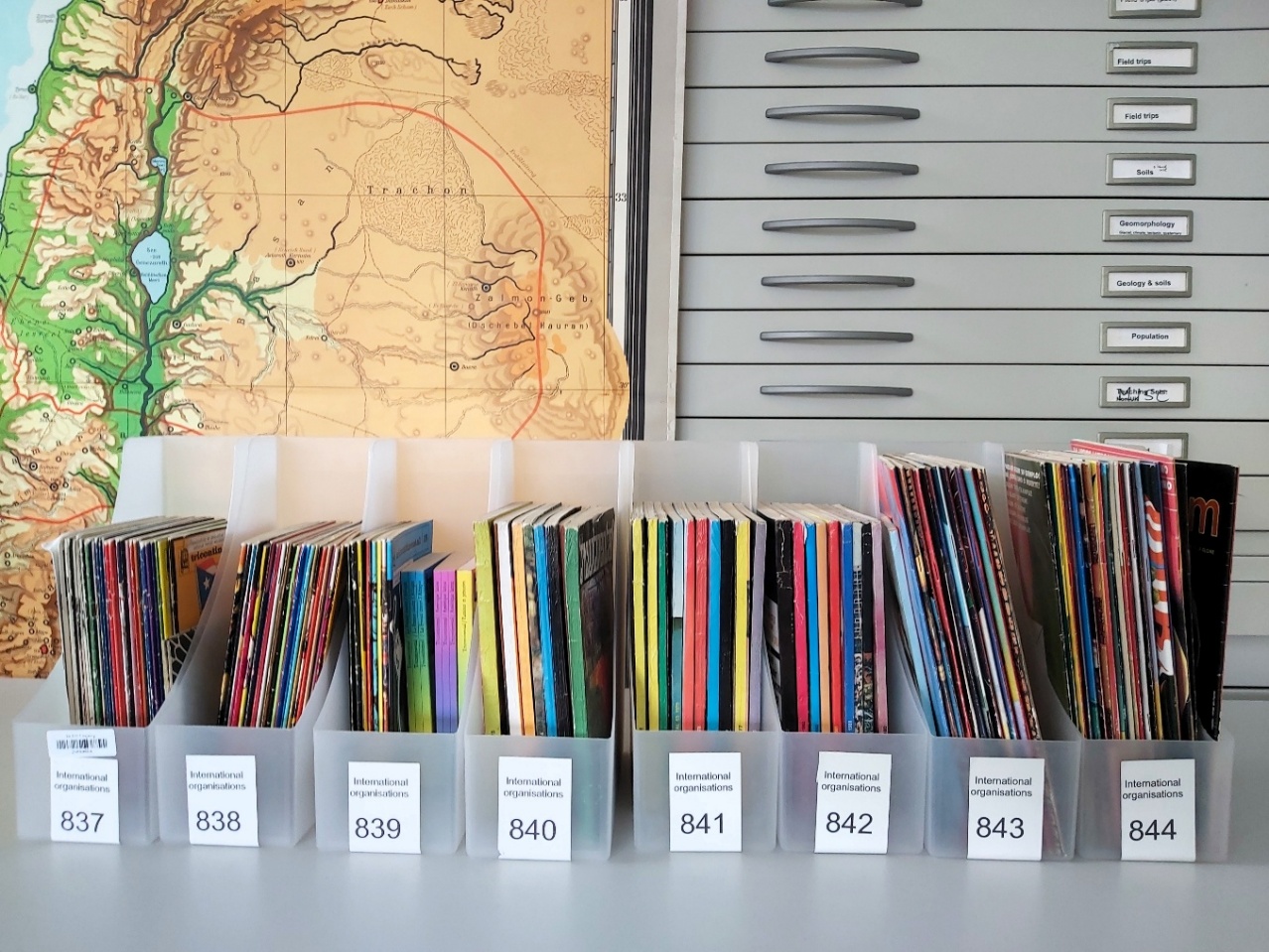

This chapter examines the Tricontinental collection housed in the British Library for Development Studies (BLDS) Legacy Collection and its use in recent critical pedagogy workshops at the University of Sussex (UoS). Through archival activation—an approach that treats collections not as passive repositories but as dynamic sites of engagement and power relations (Buchanan & Bastian, 2015)—I explore how re-activating these periodicals can generate critical dialogues on historical material struggles shaping processes of anticolonial knowledge production and learning.

My approach also draws on conjunctural analysis, which examines how social, political, and economic forces converge to define historical periods characterised by crises, contradictions and turning points (Hall & Massey, 2010)[1]. The OSPAAAL (Organization of Solidarity of the Peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America) Tricontinental periodicals emerged in the Cold War conjuncture marked by geopolitical decolonisation struggles, transnational socialist movements, and economic crises. Re-activating these materials in today’s conjuncture, marked by ‘polycrisis’ (Tooze, 2022); ‘hyper-imperialism’ (Prashad, 2024); a ‘Second Cold War’ (Schindler et al., 2024); and a white supremacist ‘New Racial Regime’ (Lentin, 2025), offers a method for connecting past and present anticolonial struggles. Through archival activation and critical pedagogy grounded in conjunctural analysis, I argue that libraries can foster spaces for critical engagement with history’s latent possibilities for political education and transformative action (Kazmi, 2024).

This chapter unfolds in three parts. It begins with an overview of the material conditions, class struggles, and modes of production shaping the creation, distribution, circulation, and preservation of Tricontinental in terms of ‘informational dialectics’ and ‘information activism.’ The second section situates these issues within the historical material specificity of their location at UoS and IDS (Institute of Development Studies) libraries, touching on the conjunctural contradictions and possibilities raised by this situatedness. The third section articulates the pedagogical affordances of archival activation in the extra-curricular classroom setting, exploring collective critical archival praxis and reparative reading as a form of liberatory library learning.

1. Tricontinental information dialectics

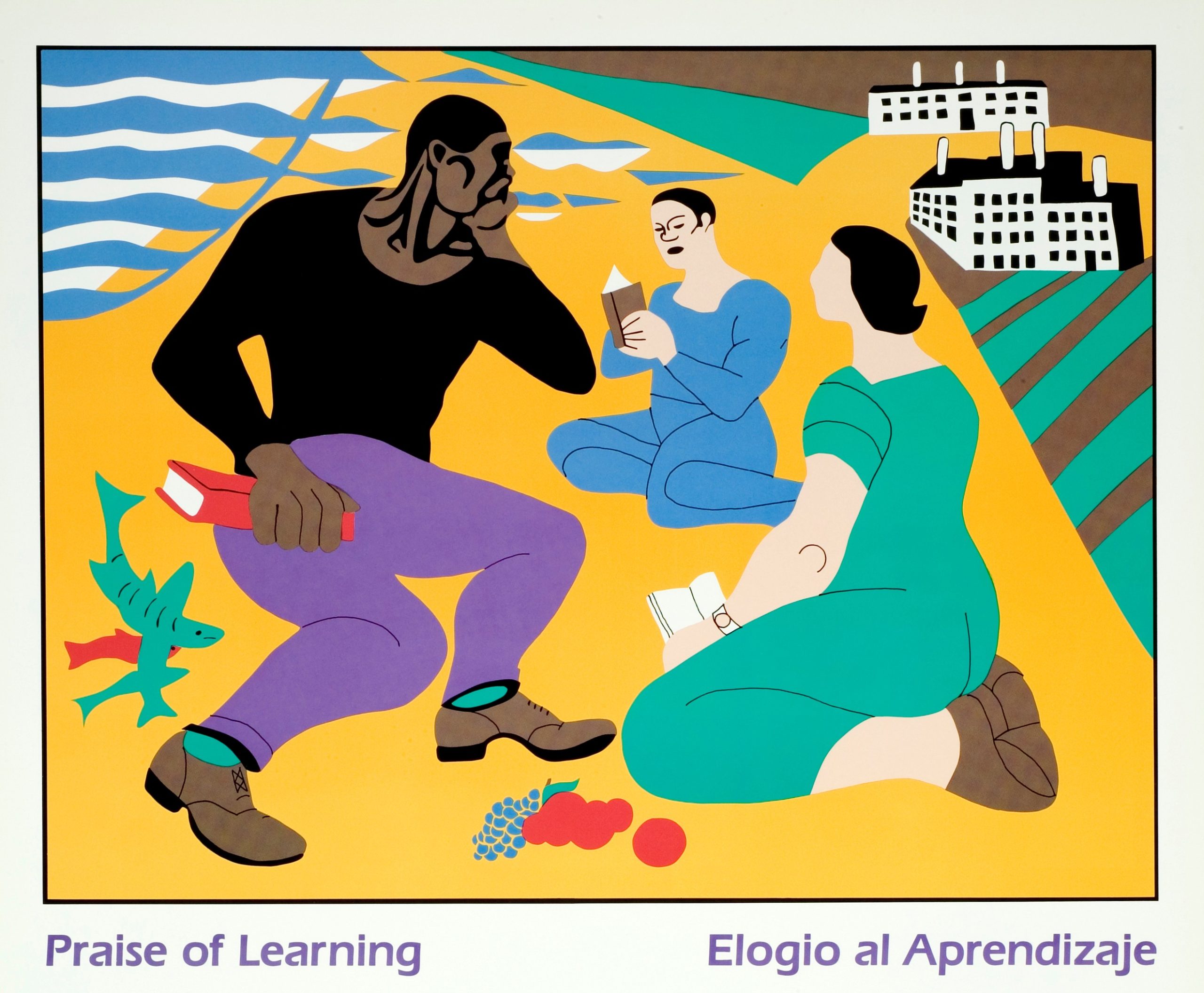

From the earliest stages of its conception, the Tricontinental movement placed practices of documentation, publication, and circulation at the core of its mission, with significant grassroots informational infrastructures developed to record and disseminate its message to the world (Young, 2018). There were two types of Tricontinental periodical: the Bulletin and the Magazine, both of which are included in the BLDS Legacy Collection holdings. The Bulletin was published monthly and functioned as a newsletter circulated among organising groups. The magazine was OSPAAAL’s ‘theoretical organ’, serving as its transnational public communication vehicle that waged a ‘war of words and images’ against imperialism using analytical reporting and striking graphic design which politically subverted Western advertising aesthetics for revolutionary ends (Macphee, 2019). It was described by Black Panther Party leader Stokely Carmicheal as ‘a bible in revolutionary circles’, and as ‘the most dangerous threat that international communism has yet made against the inter-American System’ by the Organization of American States (Tricontinental, 2019, p. 5).

Published bi-monthly from 1967 to 1990, Tricontinental Magazine produced editions in Spanish, French, Italian and English languages[2]. Content included interviews and correspondence with revolutionaries; philosophical essays; reports, appeals, and resolutions on specific movement events and meetings; and cultural contributions such as poetry, photography, and its sought-after posters[3]. Economic reporting on colonial resource extraction is presented alongside cultural resistance accounts; graphic arts and poetry are juxtaposed with strike reports; embodying the unity of material and ideological class struggle on ink and paper. The OSPAAAL publishing team followed an anticapitalist ‘countercultural media ethos’, including open copyright statements which explicitly encouraged the copying and reproduction of Tricontinental content (Wilson & Lippard, 2012, p. 175).

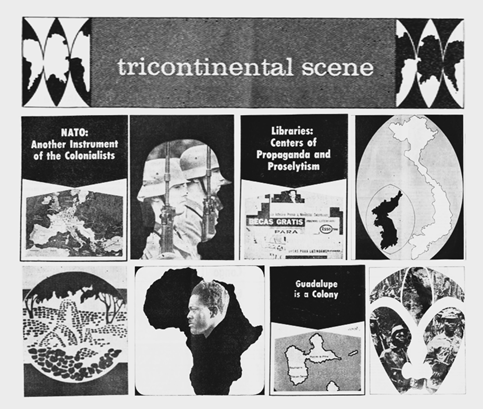

With this ‘copyleft’ principle in mind, Figure 4 below depicts a montage of images I have compiled from the ‘Tricontinental Scene’ segment of Bulletin No. 35 (February 1969), to illustrate how territories of information and power operate dialectically in this revolutionary periodical.

Geographical imagery of maps and landscapes features on multiple pages, visualising the land-based territories of anti-imperial armed struggle across the globe. The juxtaposition of text and images across these pages shows that these struggles are as much about competing territories of information as they are about those of the physical earth. A dialectics of form and content is achieved through the fusing of militant rhetoric with historical documentation, deploying sharp contradictions (imperialism vs. anti-imperialism, bourgeois knowledge vs. revolutionary knowledge) to highlight the necessity of entwined armed and intellectual struggle.

An article from this 1969 Bulletin brings this dialectic into sharp focus. Following reportage on the intensification of armed struggle in the Congo and critiques of NATO’s neocolonial foundations, on pages 15-16 is a column entitled ‘Libraries: Centers of Propaganda and Proselytism’. Its opening paragraph reads:

Imperialism has assigned libraries an important and subtle role in its penetration of Latin America. They operate in three types of institutions:

I. The official libraries of the United States

II. The private libraries of the country in question

III. Those of the Organization of American States.

It goes on to evidence how these informational tactics of American imperialism operated in each of the library types, through strategically placed librarians, educators, and promotional programmes. The segment presents libraries as ideological battlegrounds where imperialist epistemologies are challenged by revolutionary and counter-archival orders of knowledge production.

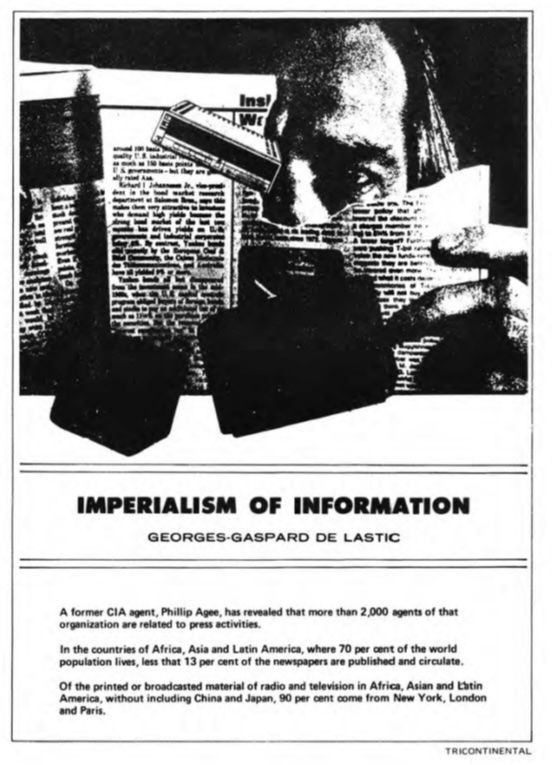

These dialectics are reinforced in Tricontinental Magazine No. 111 (1987), in a 10-page article by Georges-Gaspart De Lastic titled ‘Imperialism of Information’. This report uses statistical evidence to highlight the U.S.A.’s and Western Europe’s hegemonic global monopoly on news, publishing, and telecommunications industries, underlining how the so called ‘communication explosion era’ deepens information inequality between developed and developing countries, and ‘brutally interferes in the cultural life’ of marginalised nations, especially in Africa[4](De Lastic, 1987, p. 39). De Lastic adopts the concept of information imperialism from the former President of Finland, Uroho Kekkonen, who coined it to describe:

the terrible and unacceptable inequality prevailing in the field of the international information exchange, where the information flow from the advanced capitalist countries towards the developing ones is almost one hundred times more than the flow the opposite direction! (Kekkonen, 1973, cited in De Lastic, 1987, p. 39)

He concludes urging for an intensification of the struggle to forge ‘a New International Information Order’ through allied socialist and progress forces in both the developing and capitalist countries, in a coordinated fight ‘for the democratization of information’ (De Lastic, 1987, p. 43).

Tricontinental periodicals manifest the need for critical information literacy campaigns as a core component of resistance, emphasising access to counter-hegemonic media sources as a form of material struggle against imperialism. They exemplify ‘a Global South infrastructure for pedagogy and political education’ (Kazmi, 2024, p. 183), in this case a tool for analysing the politics of library and information spaces of knowledge production and learning. This brings us to the ‘library scene’ of UoS and IDS: how did the Tricontinental serials come to be part of the BLDS Legacy Collection in this English academic institution in Southeast England? And what kinds of imperial ‘legacies’ are embedded in the library?

2. Library conjunctures, legacies, and societal provenance

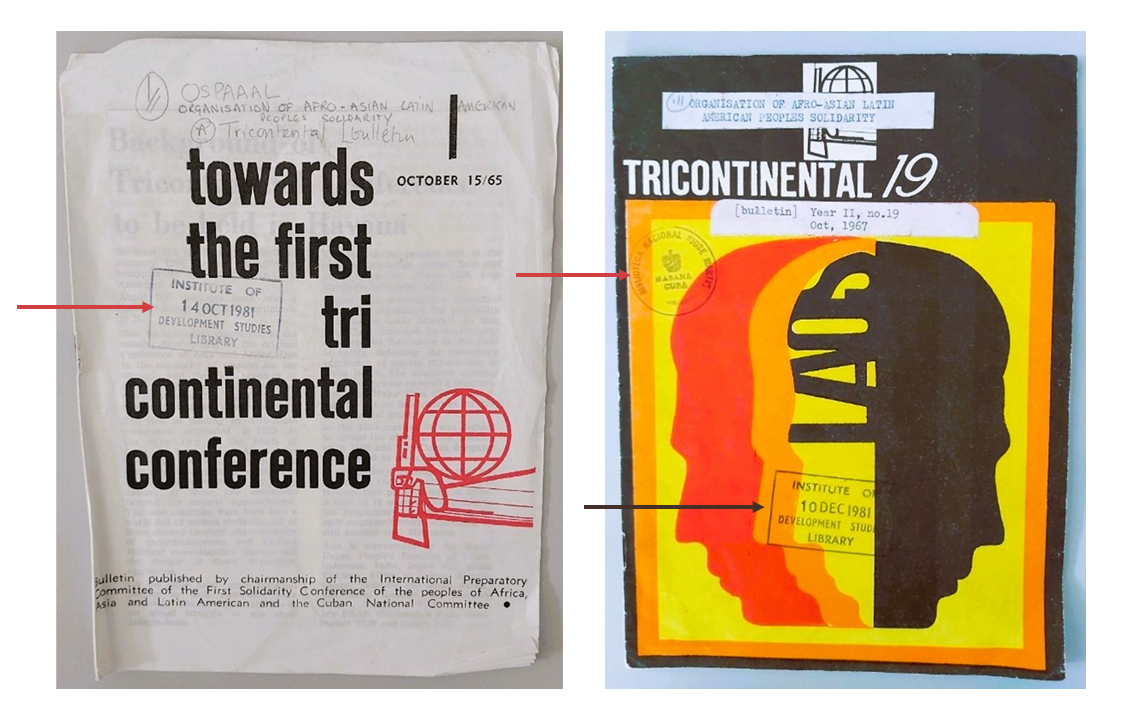

The first Tricontinental Bulletin was published by OSPAAAL in October 1965, titled Towards the First Tricontinental Conference. A rare copy of this 14-page pamphlet printed on gossamer airmail paper is held in the BLDS Legacy collection. The pamphlet’s cover includes the first published instance of the Tricontinental logo, a red bold graphic of a globe balanced between the right-angled barrel and arm of a gun pointing skyward, a revolutionary finger poised on the trigger, ready to fire information at the reader. The contents of this pamphlet publicises the organising preparations and agendas for the ‘Conference of solidarity with the peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America’: an unparalleled 12-day event convening delegations from African, Asian and Latin American liberation movements which took place in Havana on 15 January 1966.[5]

When this inaugural Tricontinental Bulletin was published in 1965, UoS Library (opened 1964) was in its infancy, and its sister organisation IDS (which had its own library) was still being built, to be opened the following year in 1966 (Corble, 2022; Jolly, 2008). The IDS Library stamp imprinted on the 1965 Bulletin is dated 14th October 1981, a provenancial marker (Wickenden, 2020) which indicates its date of acquisition some sixteen years after its original publication. As the image on the right of Figure 7 shows, the IDS Library date stamp marking its acquisition of Tricontinental Bulletin no. 19 (published October 1967) is 10th December 1981. Interestingly, this item also bears another library stamp, that of the Biblioteca Nacional de Cuba José Martí (the national library of Cuba in Havana). As Schmiedecke highlights, the international circulation of OSPAAAL periodicals was challenging both on infrastructural levels and because their content was flagged as terrorist many countries, hence ‘[d]ifferent means were employed to distribute them either openly or clandestinely’, often via postal correspondence mediated by radical redistribution networks (2024, p. 399). Despite its reputation for being a progressive institution attracting counter-cultural and left-wing scholars, it seems unlikely that IDS had an documents exchange agreement with OSPAAAL or the Cuban national library in the late 1960s.

IDS was established as an autonomous national institution in 1966 by the UK Ministry of Overseas Development with the cooperation of UoS. This was in response to a 1963 report by the former head of the British Civil Service, Lord Bridges, which ‘argued that the leaders of developing countries urgently needed training in the principles of public administration’ to help counter the tendencies of ‘underdeveloped’ former colonies in becoming ‘breeding grounds for communism’ (Cragoe, 2020, p. 67; Seers, 1977, p. 8). As well as developing training and policy-making resources for developing nations, a core feature of IDS’ purpose was to be ‘a national centre for documentation on Third World development,’ with a national library whose collection focused on four distinct bibliographic fields of international documentation in this interdisciplinary arena:

(1) government publications of developing countries, (2) titles issued by and about parastatal organisations in these countries, (3) publications of other institutions active in development studies and (4) records of specified United Nations and other international agencies. (Gorman, 1979, p. 1).

As an anti-imperial transnational liberation organisation, OSPAAAL does not easily fit into this schema since it defies the neocolonial construction and conception of the nation state and its informational logics of knowledge production and thereby resists classification. Such epistemic disobedience (Mignolo, 2009) is likely to have presented dilemmas for early IDS librarians, who acknowledged that many ‘international organisations’ defy official classification criteria, leaving ‘the practitioner once more forced to rely on his own ingenuity in deciding whether a particular body is international’ (Gorman, 1979, p. 3).

This raises questions about the BLDS Tricontinental items’ ‘societal provenance’: an archival science term coined by Tom Nesmith to define the informational dialectics of archival records, which ‘”have a back story and an afterlife; they have breadth and depth. They lead a double social life; they ‘reflect and shape societal processes”‘ (Piggott, 2012, p. 3, citing Nesmith, 2006, p. 359). How and why were Tricontinental serials acquired into the IDS Library collections? Who was reading them at Sussex and how was their learning applied across the timespans and transnational distances that bridged their points of origin with their destination? We may never know the answers to these questions without accounts from library workers and users with living memory of the time[6].

We do know that the IDS library acquisition policy in the 1970s was to obtain ‘documentation of international organisations in any of four ways: deposit, exchange, standing order and blanket subscription, individual request (either complimentary or by payment)’ (Gorman, 1979, p. 3). Perhaps, then, a more likely acquisition scenario is that OSPAAAL periodicals were requested in the early 1980s by individuals at Sussex who had activist connections to Tricontinental movements. The Bulletin correspondence columns often included appeals from activists around the world asking to be included in the distribution networks, as shown in the letter from a Norwegian student socialist leader below (Figure 10).

The conjunctural shape of the 1980s was different to that of the 1960s. Pivoting on the crises and contradictions of the mid-1970s, by the early 1980s global capitalism had mutated into an economic world order ruled by neo-liberal forces and ‘common-sense’ individualism. This was unleashed by ‘Reaganomics’ in the US and ‘Thatcherism’ in the UK, which blended free-market ideology with nationalism, law-and-order rhetoric, and racist anti-immigrant sentiment (Aglietta, 1982; Hall, 2021). As indicated in the excerpts from the 1987 issue of Tricontinental Magazine analysed in the previous section, transnational socialist struggles faced seismic new challenges to fight against economic, cultural and information imperialism. Meanwhile in the comparatively privileged enclave of IDS at Sussex, by the 1980s it had become a global leader in Development Studies, its library boasting the largest collection of development research in Europe. However, the library was also facing government funding cuts alongside complex challenges in indexing and communicating the ‘visibility’ its international documentation holdings (Rogers, 1982).

Fast forward another twenty-five years into the next conjuncture of advanced neoliberal societal provenance. By 2017, funding cuts led the IDS Library to close. Its librarians were made redundant, their decades of institutional memory of how the collection had been developed (with a bespoke classification system) leaving with them. The collection became inactive in the IDS basement for a couple of years until a Wellcome Trust grant awarded jointly to UoS and IDS in 2019 enabled it to be made accessible as a ‘legacy’ collection, i.e., a collection no longer grown via new acquisitions for current development studies materials but rather one preserved for its uniquely distinctive historical significance and value (Allen, 2019; Cullingford et al., 2014). Renamed the BLDS Legacy Collection, the original IDS Library collection was then weeded, sorted, re-catalogued and integrated into the UoS Library special collections (Marchant-Wallis, 2021); paying ‘particular attention to how the collection can be decolonised and, described and catalogued in a sensitive and appropriate way’ (Andrews, 2020; see also chapters by Bethany Collard, and by Danny Millum, in this volume).

The conjunctural contradictions of this work, however, relates to it being in, owned and controlled by an academic institution in the global north which benefits from wealth and knowledges extracted from the south (Jimenez et al., 2022). The name British Library of Development Studies Legacy Collection (emphasis added) signifies an imperial position of epistemic sovereignty that is denied many cultural institutions of the global south. Moreover, as with the majority of the world’s academic libraries, this collection now follows the Library of Congress classification system, a so-called ‘universal’ system which is rooted in US imperialist forms of governance and racist taxonomies (Adler, 2017; Baron & Broadley, 2019). Perhaps, then, the library can never truly be decolonised without abolition (Beras & Drake, 2023; Matthews, 2018), but that should not stop us from engaging in liberatory and reparative forms of library and archival learning. As Phil Cohen argues, ‘the archival significance of objects cannot be secured by their mode of production or material provenance alone’ (2018, p. 9). Indeed, grasping the contemporary significance of archival materials such as Tricontinental and related revolutionary periodicals must be grounded in consciousness of both the colonial institutional legacies and infrastructures that encase them, and the ways in which they can also resist those legacies. This can be achieved through educative interventions which generate ‘new and critically engaged forms of dialogue both within and beyond the material itself’ (Cohen, 2018, p. 6).

3. Towards reparative reading and liberatory learning

Universities [and their libraries] are institutions that hinge around filtering and sifting knowledge and people. I believe that we need to constantly challenge and push open what counts as ‘learning’ at universities to the formal and informal knowledge and learning embedded in other spaces, experiences and struggles. (Choudry, 2020, pp. 28–29, insertion mine)

The reparatively positioned reader engages with surprise and contingency to organize the fragments and part objects she encounters and creates: “Because the reader has room to realize that the future may be different from the present, it is also possible for her to entertain such profoundly painful, profoundly relieving, ethically crucial possibilities as that the past, in turn, could have happened differently from the way it actually did. (Dirckinck-Holmfeld, 2021, p. 446 citing Eve Sedgewick, 2003, p. 146)

Reframing discussions of decolonisation in the light of anticolonial thought – as the theory and practice of anticolonialism – gives grounding, heft and direction to them, enabling rich questions to be posed and answered towards the wider horizon of making another world possible. (Gopal, 2021, p. 873)

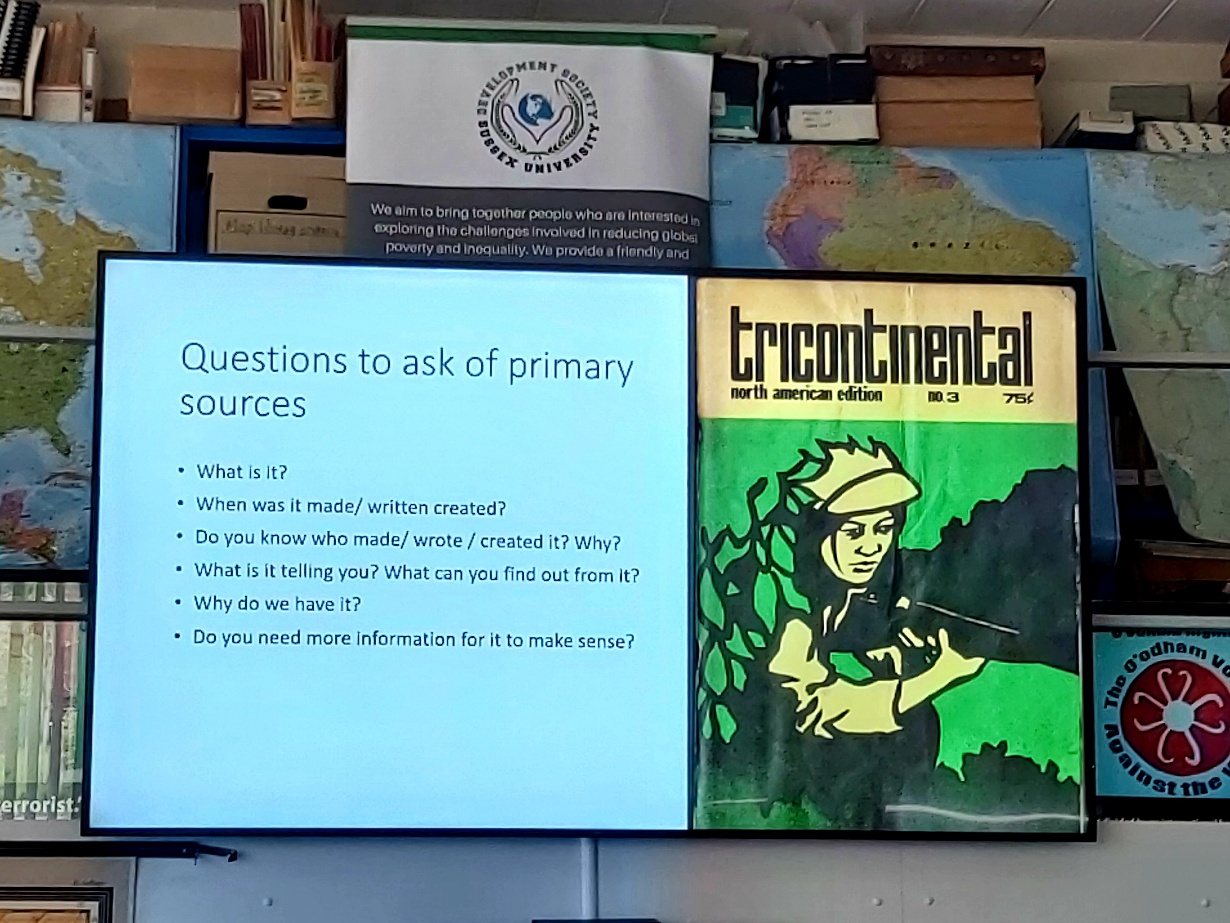

The ‘Tricontinental, Mujeres, and the Worlds they Invite us to Imagine’ workshop at Sussex (Millum, 2024a), and the resulting book you are reading now, offers a taste of what Andrew Flinn calls history activism: ‘collectively creating knowledge and learning from the past for the present and future’, or in other words, ‘making history of struggle part of the struggle’ (Choudry & Vally, 2017, p. 21). These extra-curricular workshops took students and faculty outside the ‘teaching machine’ (Spivak, 1993) of their usual classrooms, and positioned librarians and library materials outside of the library, re-locating collaborative learning in a collective space of anticolonial archival activation. This approach ‘sets material resonating’ (MayDay Rooms, n.d.), allowing past and future struggles to converge in new, unpredictable ways.

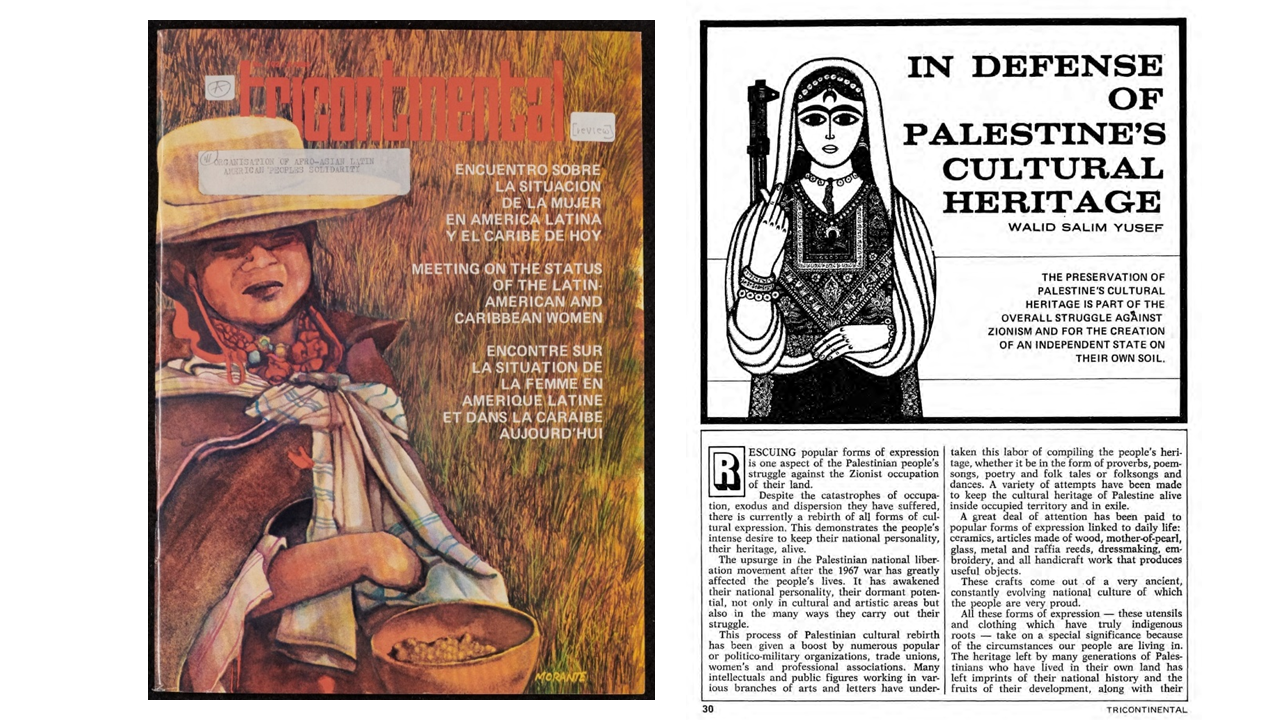

There is great scope to build on the success of this collaborative library workshop, which harnesses the power of archival activation as a mode of critically engaging with social justice – through situated learning, teaching and research[7]. As a form of critical pedagogy, centring revolutionary papers in such learning spaces ‘can challenge the postcolonial theoretical emphasis on the bordered nation, the canonical status of anglophone writing, and the privileging of a small group of male anticolonial figures like Nehru or Mandela’ (2024, p. 195). Countless articles in Tricontinental Magazine analyse the interconnections between race, class, in anticolonial movements, for example, issue No. 102 features a report on the ‘Meeting on the Status of Women in Latin America and the Caribbean Today’ (December 1985 [Figure 12]). This intersectional lens provides students with a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of global power dynamics and feminisms, challenging simplified or monolithic representations of anti-colonial resistance (Molinero & and Ortega López, 2024).

Student-led discussions at the Sussex workshop raised salient points about the relevance of past intersectional anticolonial struggles to those of the present, reminding us of Edward Said’s dialectical concern that ‘we should keep before us the prerogatives of the present as signposts and paradigms for the study of the past’ (1993, p. 61). The workshop took place spring 2024, a time when student activist ‘liberation encampments’ fighting for anticolonial justice for Palestinian people proliferated across university campuses around the world, including one at Sussex positioned directly outside the library (AJLabs, 2024; Duda, 2025; Freeman, 2025; Summers, 2024). As historian Jacob Norris highlighted in his workshop talk, Tricontinental periodicals include extensive content that charts the Palestinian liberation struggles throughout the twentieth century. For example, magazine No. 97 (1985) features an article by Walid Salim Usef titled ‘In defense of Palestine’s cultural Heritage’ (pp. 30-36 [Figure 12]). Usef presents a powerfully prescient and poignant warning against the grave realities of settler colonial epistemicide and ethnocide that we are tragically witnessing as the ongoing genocide of Palestinian peoples unfolds on the global stage today, which has seen Palestinian libraries, archives and universities destroyed (Librarians and Archivists with Palestine, 2024; Moaswes, 2024).

Engaging meaningfully with these anticolonial histories and ongoing struggles is necessarily difficult work, especially in the current hyper-imperialist global conjuncture. It is work that takes time and needs to be done carefully and collectively and re-iteratively, cultivating spaces of reparative reading (Smith, 2021) and hopeful solidarities (A. Clarke et al., 2024) between the cracks that are opened up by the transnational and transgenerational crises in which we find ourselves and each other. Student feedback from the workshop highlighted that they wanted more time, demonstrating an appetite for digging deeper into radical histories (Millum, 2024b). This underscores the notion that ‘[i]f history is a way of knowing the world which can work as an antidote to catastrophic thought then there may be virtue in the fact that – most often – historical knowledge necessarily moves slowly’ (Alexander et al., 2017, p. 2).

In lieu of a conclusion (I have already exceeded the spatial limits of this chapter that is struggling to contain the ‘slow knowledge’ in which it is immersed!), I will speed up by giving the last words to radical librarians and knowledge justice scholars Sofia Leung and Jorge López-McKnight. Their fiery intervention speaks to the urgency of continuing to challenge the ‘information imperialism’ which Tricontinental publications subverted through revolutionary means of knowledge production and education. They highlight how truly liberatory library praxis must go far beyond highlighting previously hidden histories or diversifying voices in collections and curricula; it is a method of dismantling the imperial logics of knowledge infrastructures and collectivising in an anticolonial politics of refusal and re-making.

Actually, we’re going deeper. We want this to burn bright, to incinerate these pages. Turn up the volume. Better yet, open the window and turn the speakers out to the world because this needs to reach everything—air, water, land, you. Because there is nothing left. We want (y)our instruction to be frightening—too beautiful, too heavy with love; travelling through landscapes and time, listening and speaking, seeing and remembering, witnessing as everything is falling apart, disintegrating. We must set it off and remake critical library instruction, critical information literacy, shit, libraries as we understand them because there is nothing left. And because there is nothing left, it means this is the beginning. (Leung & López-McKnight, 2020, p. 23)

References

Adefila, A., Teixeira, R. V., Morini, L., Garcia, M. L. T., Delboni, T. M. Z. G. F., Spolander, G., & Khalil-Babatunde, M. (2022). Higher education decolonisation: #Whose voices and their geographical locations? Globalisation, Societies and Education, 20(3), 262–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2021.1887724

Adler, M. (2017). Classification along the color line: Excavating racism in the stacks. Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies, 1(1), Art. 1. https://doi.org/10.24242/jclis.v1i1.17

Aglietta, M. (1982). World capitalism in the Eighties. New Left Review, I/136, 5–41. https://newleftreview.org/issues/i136/articles/michel-aglietta-world-capitalism-in-the-eighties

AJLabs. (2024, April 29). Mapping pro-Palestine college campus protests around the world. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/4/29/mapping-pro-palestine-campus-protests-around-the-world

Alexander, S., Schwarz, B., & Whitehead, A. (2017). Radical histories. History Workshop Journal, 83, 1–2. https://www.jstor.org/stable/i40194127

Allen, S. (2019, March 15). Wellcome Trust grant to create new legacy for the British Library for Development Studies. The University of Sussex. https://www.sussex.ac.uk/broadcast/read/48110

Andrews, J. (2020, February 19). Unfolding the history of international development. Institute of Development Studies. https://www.ids.ac.uk/opinions/unfolding-the-history-of-international-development/

Arday, J., Zoe Belluigi, D., & Thomas, D. (2021). Attempting to break the chain: Reimaging inclusive pedagogy and decolonising the curriculum within the academy. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 53(3), 298–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1773257

Baron, J., & Broadley, S. (2019, December 19). Change the subject [Documentary]. https://collections.dartmouth.edu/archive/object/change-subject/change-subject-film

Beras, K., & Drake, J. M. (2023). From repositories of failure to archives of abolition. In A. Prescott & A. Wiggins (Eds.), Archives: Power, truth, and fiction (p. 0). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198829324.013.0026

Bhambra, G. K., Gebrial, D., & Nişancıoğlu, K. (Eds.). (2018). Decolonising the university. Pluto Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv4ncntg.1

Buchanan, A., & Bastian, M. (2015). Activating the archive: Rethinking the role of traditional archives for local activist projects. Archival Science, 15(4), 429–451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-015-9247-3

Cario, R. V., Luis. (2021, January 15). The Tricontinental conference: The right to our history. Utopix. https://utopix.cc/content/the-tricontinental-conference-the-right-to-our-history/

Carr, A., Alchazidu, A., Booth, W., Constanzo, P., Bonilla, G., Tineo, P., & Chudova, K. (2023). Epistemic (in)justice: Whose voices count? Listening to migrants and students. Journal of Comparative & International Higher Education, 15(5), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.32674/jcihe.v15i5.5811

Caswell, M. (2021). Urgent archives: Enacting liberatory memory work. Routledge. https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/63368

Chantiluke, R., Kwoba, B., & Nkopo, A. (2018). Rhodes must fall: The struggle to decolonise the racist heart of empire. Zed books.

Chigudu, S. (2020). Rhodes must fall in Oxford: A critical testimony. Critical African Studies, 12(3), 302–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681392.2020.1788401

Choudry, A. (2020). Reflections on academia, activism, and the politics of knowledge and learning. The International Journal of Human Rights, 24(1), 28–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2019.1630382

Choudry, A., & Vally, S. (Eds.). (2017). Reflections on knowledge, learning and social movements: History’s schools. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315163826

Choudry, A., & Vally, S. (Eds.). (2020). The University and social justice: Struggles across the globe. Pluto Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvx077w4

Clarke, A., Rogaly, B., & Senker, C. (2024). Hope as a practice in the face of existential crises: Resident-activist research within and beyond the academy. Area, 56(3), e12952. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12952

Clarke, J. (2023). The battle for Britain: Crises, conflicts and the conjuncture (1st ed.). Bristol University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.3252828

Cohen, P. (2018). Archive that, comrade! Left legacies and the counter culture of remembrance. PM Press.

Corble, A. (2022, November 15). Many happy returns? Reading the November 1964 birth of University of Sussex Library through a (de)colonial lens. Decolonial Maps of Library Learning. https://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/decolonialmapsoflearning/2022/11/15/many-happy-returns-reading-the-november-1964-birth-university-of-sussex-library-through-a-decolonial-lens/

Cragoe, M. (2020). Sussex: Cold War campus. In M. Taylor & J. Pellew (Eds.), Utopian universities: A global history of the new campuses of the 1960s (pp. 56–71). Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

Crilly, J., & Everitt, R. (2021). Narrative expansions: Interpreting decolonisation in academic libraries. Facet Publishing.

Cushing, L. (2023a). Library culture. Docs Populi. https://www.docspopuli.org/LibraryCulture.html

Cushing, L. (2023b). How Poster Art of the ‘Long 1960s’ Fuelled International Solidarity. The Brown Journal of World Affairs, 29(2), 1–18. https://chcoalition.org/how-poster-art-of-the-long-1960s-fueled-international-solidarity/

Cushing, L. (2022). Archiving as Social Justice Practice—UC Berkeley Summer Bridge Program. Docs Populi. https://www.docspopuli.org/articles/ArchivingJustice.html

Cushing, L. (2003). Revolución! Cuban Poster Art. Chronicle Books. https://openlibrary.org/books/OL8002245M/Revolucion!

Cullingford, A., Peach, C., & Mertens, M. (2014). Unique and distinctive collections: Opportunities for research libraries. RLUK. https://www.rluk.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/RLUK-UDC-Report.pdf

De Lastic, G.-G. (1987). Imperialism of information. Tricontinental Magazine, 111(3), 34–40. Freedom Archives. https://freedomarchives.org/Documents/Finder/DOC51_scans/51.Cuba.Tricontinental.111.pdf

Dirckinck-Holmfeld, K. (2021). Reparative. In N. B. Thylstrup, D. Agostinho, A. Ring, C. D’Ignazio, & K. Veel (Eds.), Uncertain archives. The MIT Press. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9357777

Duda, N. (2025, March 3). Pro-Palestinian student protests are nothing new. The Progressive Magazine. https://progressive.org/api/content/c73e91d2-f874-11ef-991f-12163087a831/

Enslin, P., & Hedge, N. (2024). Decolonizing higher education: The university in the new age of Empire. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 58(2–3), 227–241. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopedu/qhad052

Freeman, J. (2025). ‘There was nothing to do but take action’: The encampments protesting for Palestine and the response to them (185). HEPI. https://www.hepi.ac.uk/2025/01/30/there-was-nothing-to-do-but-take-action-the-encampments-protesting-for-palestine-and-the-response-to-them/

Gopal, P. (2021). On decolonisation and the University. Textual Practice, 35(6), 873–899. https://doi.org/10.1080/0950236X.2021.1929561

Gorman, G. E. (1979). International organisations and development studies documentation. Government Publications Review (1973), 6(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/0093-061X(79)90002-9

Gray, E. (2021). The neo-colonial political economy of scholarly publishing: Its UK-US origins, Maxwell’s role, and implications for sub-Saharan Africa. The African Journal of Information and Communication (AJIC), 27, Art. 27. https://doi.org/10.23962/10539/31367

Hall, S. (2021). The hard road to renewal: Thatcherism and the crisis of the left. Verso.

Hall, S., & Massey, D. (2010). Interpreting the crisis. Soundings: A Journal of Politics and Culture, 44, 57–71. https://doi.org/10.3898/136266210791036791

Heleta, S. (2023). Critical review of the policy framework for internationalisation of Higher Education in South Africa. Journal of Studies in International Education, 27(5), 817–833. https://doi.org/10.1177/10283153221121395

Hlatshwayo, M. N. (2021). The ruptures in our rainbow: Reflections on teaching and learning during #RhodesMustFall. Critical Studies in Teaching and Learning (CriSTaL), 9(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.14426/cristal.v9i2.492

Jimenez, A., Vannini, S., & Cox, A. (2022). A holistic decolonial lens for library and information studies. Journal of Documentation, 79(1), 224–244. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-10-2021-0205

Jolly, R. (2008). A short history of IDS: A personal reflection (338; IDS Discussion Paper). Institute of Development Studies. https://www.ids.ac.uk/publications/a-short-history-of-ids-a-personal-reflection/

Kazmi, S. (2024). The periodical as political educator: Anticolonial print and digital humanities in the classroom and beyond. Radical History Review, 2024(150), 183–204. https://doi.org/10.1215/01636545-11257460

Keith, B. W., Taylor, L. N., & Renwick, S. (Eds.). (2024). Liberatory librarianship: Stories of community, connection, and justice. ALA Editions.

Lentin, A. (2025). The new racial regime: Recalibrations of white supremacy. Pluto Press.

Leung, S. Y., & López-McKnight, J. R. (2020). Dreaming revolutionary futures: Critical race’s centrality to ending white supremacy. Communications in Information Literacy, 14(1), 12–26. https://doi.org/10.15760/comminfolit.2020.14.1.2

Librarians and Archivists with Palestine. (2024). Israeli damage to archives, libraries, and museums in Gaza: a preliminary report. Librarians and Archivists with Palestine. October 2023–January 2024. https://librarianswithpalestine.org/gaza-report-2024/

Lorne, C., Thompson, M., & Cochrane, A. (2024). Thinking conjuncturally, looking elsewhere. Dialogues in Human Geography, 14(3), 499–503. https://doi.org/10.1177/20438206231202825

Macphee, J. (2019, February 28). Constructing Third World struggle: The design of the OSPAAAL & Tricontinental. The Funambulist Magazine. https://thefunambulist.net/magazine/22-publishing-struggle/constructing-third-world-struggle-design-ospaaal-tricontinental-josh-macphee

Marchant-Wallis, C. (2021, April 30). Well that’s a lot of pamphlets…. The British Library for Development Studies Legacy Collection. https://bldslegacycollection.uk/2021/04/30/well-thats-a-lot-of-pamphlets/

Matthews, S. (2018). Confronting the colonial library: Teaching Political Studies amidst calls for a decolonised curriculum. Politikon, 45(1), 48–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/02589346.2018.1418204

MayDay Rooms. (n.d.). Activation. MayDayRooms. Retrieved 30 March 2025, from https://maydayrooms.org/activation/

Mbembe, A. (2016). Decolonizing the university: New directions. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 15(1), 29–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474022215618513

Mignolo, W. D. (2009). Epistemic disobedience, independent thought and decolonial freedom. Theory, Culture & Society, 26(7–8), 159–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276409349275

Millum, D. (2024a, January 22). Student researchers in the BLDS Legacy Collection: Tricontinental, Mujeres, and the worlds they invite us to imagine. The British Library for Development Studies Legacy Collection. https://bldslegacycollection.uk/2024/01/22/student-researchers-in-the-blds-legacy-collection-tricontinental-mujeres-and-the-worlds-they-invite-us-to-imagine/

Millum, D. (2024b, May 16). Exploring different approaches to using Tricontinental and Mujeres in your research from a library perspective. The British Library for Development Studies Legacy Collection. https://bldslegacycollection.uk/2024/05/16/report-on-the-workshop-exploring-different-approaches-to-using-tricontinental-and-mujeres-in-your-research-from-a-library-perspective/

Moaswes, A. (2024, February 2). The epistemicide of the Palestinians: Israel destroys pillars of knowledge. Institute for Palestine Studies. https://www.palestine-studies.org/en/node/1655161

Molinero, A. G., & and Ortega López, T. M. (2024). Voices of women in the global south: Tricontinental magazine and the new feminist narrative (1967-2018). Women’s History Review, 33(3), 313–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/09612025.2023.2223813

Parrott, J. (n.d.). A graphic revolution: The new archive (No. 19). Not Even Past. Retrieved 1 April 2025, from https://notevenpast.org/tag/ospaaal/

Peck, J. (2023). Situating method: Exploring conjunctural capitalism(s). In J. Peck (Ed.), Variegated economies (p. 0). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190076931.003.0010

Peck, J. (2024). Articulating conjunctural analysis. Dialogues in Human Geography, 14(3), 504–508. https://doi.org/10.1177/20438206241242471

Phipps, A., & McDonnell, L. (2021). On (not) being the master’s tools: Five years of ‘changing university cultures’. Gender and Education, 0(0), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2021.1963420

Piggott, M. (2012). Archives and societal provenance Australian essays. Chandos Pub.

Prashad, V. (2024, January 29). Hyper-imperialism. Consortium News. https://consortiumnews.com/2024/01/29/hyper-imperialism/

Rogers, M. H. (1982). The visibility of international socio-economic development agency documentation. In T. D. Dimitrov & L. Marulli-Koenig (Eds.), International documents for the 80’s: Their role and use. Proceedings of the 2nd World Symposium on International Documentation Brussels—1980 (pp. 48–58). De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110842579-010

Said, E. W. (1993). Culture and imperialism. Chatto & Windus.

Schindler, S., Alami, I., DiCarlo, J., Jepson, N., Rolf, R., Steve, Bayırbağ, M. K., Cyuzuzo, L., DeBoom, M., Farahani, A. F., Liu, I. T., McNicol, H., Miao, J. T., Nock, P., Teri, G., Vila Seoane, M. F., Ward, K., Zajontz, T., & Zhao, Y. (2024). The second Cold War: US-China competition for centrality in infrastructure, digital, production, and finance networks. Geopolitics, 29(4), 1083–1120. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2023.2253432

Seers, D. (1977). Back to the ivory tower? The professionalisation of development studies and their extension to Europe. Institute of Development Studies. https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/articles/journal_contribution/Back_to_the_ivory_tower_The_professionalisation_of_development_studies_and_their_extension_to_Europe/26468524/1

Smith, C. (2021, December 20). Reparative readings. Anatomies of Power. https://anatomiesofpower.wordpress.com/2021/12/20/reparative-readings/

Spivak, G. C. (1993). Outside in the teaching machine. Routledge.

Summers, A. (2024, May 15). Liberation encampment fights for Sussex to fly the flag of Palestine. The Badger. https://thebadgeronline.com/2024/05/liberation-encampment-fights-for-sussex-to-fly-the-flag-of-palestine/

Tooze, A. (2022, October 28). Welcome to the world of the polycrisis. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/498398e7-11b1-494b-9cd3-6d669dc3de33

Tricontinental. (2019). The art of the revolution will be internationalist (Dossier no. 15). Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. https://thetricontinental.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/190408_Dossier-15_EN_Final_Web.pdf

Wickenden, A. (2020, June 21). Things to know before beginning, or: Why provenance matters in the library. Inscription. https://inscriptionjournal.com/2020/06/21/things-to-know-before-beginning-or-why-provenance-matters-in-the-library/

Wilson, T., & Lippard, L. R. (2012). Paper walls: Political posters in an age of mass media. In E. Auther & A. Lerner (Eds.), West of center (NED-New edition, pp. 162–181). University of Minnesota Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.cttttdgj.14

Young, R. J. C. (2018). Disseminating the Tricontinental. In The Routledge handbook of the Global Sixties (pp. 517–547). Routledge.

- The conversation between Stuart Hall and Doreen Massey cited here is a good entry point to understanding conjunctural analysis. For a more recent and comprehensive sources on this methodology, see (J. Clarke, 2023; Lorne et al., 2024; Peck, 2023, 2024). ↵

- Further issues of the magazine published between the mid-1990s and early 2000s. Some Arabic editions were produced in the early 1980s in Beirut, but these were curtailed by the bombing of the printing press by Israel (Young, 2018, p. 352). ↵

- Thanks to the work of librarian and archivist Lincoln Cushing, digitised copies of the posters and their metadata are available online at: https://www.docspopuli.org/CubaWebCat/gallery-01.html (Cushing, 2003: Parrott, n.d.). In a recent article on the power of these posters, Cushing states: 'Turning an increasingly critiqued popular meme on its head, the Cubans created an anti-Imperialist Playboy pinup. This experiment proved to be the most effective poster dissemination system yet conceived. Between 1966 and 1990, Tricontinental's circulation peaked in 1989 at 30,000 copies and reached 87 countries. OSPAAAL closed down in June 2019.' (Cushing 2023b, p.4). ↵

- As Eve Grey (2021) evidences, the same argument strongly applies to the neocolonial global political economy of the scholarly publishing industry. ↵

- For a detailed analysis of this inaugural OSPAAAL Bulletin see 'Disseminating the Tricontinental' (Young, 2018, pp. 518-520). For an accessible summary and analysis of the conference see 'The Tricontinental Conference: the right to our history' (Cario, 2021) ↵

- As part of my current Leverhulme-funded research, I hope to conduct an oral history interview with one of the IDS librarians who was active in collection development at the time. ↵

- Inspiration for developing inclusive curricula can be drawn from Lincoln Cushing’s (2022) 'Archiving as Social Justice Practice' summer school programme at UC Berkley. ↵