Topic 12: Nature conservation

Brief Encounter

Brief Encounter

Noticing what matters to you and other species

-

Create a map of the grounds around your educational buildings or an area of them. Mark on your map, in any way you choose, 10 things that you feel are important to include.

-

As a whole group, share your maps. Discuss what you marked, how, and why you felt it was important to include the things you did.

-

Having compared and discussed your maps and what you each marked, is there anything you would change on your own map now? Why?

-

As a group, how might you create a range of categories for the different things that you marked on your maps?

-

Why might you all have noticed and prioritised different things? What might this tell us about what matters to each of us?

-

Pick a plant or animal species that uses the grounds as well. Imagine them looking at your map. Of all the things marked on your map, which might they have marked too? What else might they have marked? What does that tell us about what matters to this species?

Opportunities for Embracing Uncertainty

Uncertainty is integral to this activity, with each person/group likely to notice and map different things, as well as the logic of how they choose to categorise the diversity of what is noticed. What they notice will be determined by multiple factors such as feelings and connection to the place, identities and culture, knowledge, prior experiences and memories, likes/dislikes, and their particular role within the organisation, as well as wider experience of the outdoors. Students are asked to identify their own categories, and to explore the multiple ways this might be done. Examples of categories that you might share or probe with the students include: types of objects (trees, insects, natural objects, buildings, equipment, technology, waste; etc); sensory factors (size, shape, colour, sound, smell, aesthetic, etc.); utility (play, work, infrastructure, transport, etc.); personal connections (memories; experiences; imaginary); environmental factors (carbon sequestering objects, animal/plant species, soil, nitrogen fixing plants, carbon intensive objects, green technologies). Crucially, the activity engages students with thinking about the perspective of other species and how they might experience the grounds differently. This activity links well to Topic 15: ‘Creating a Global Agreement’ and in particular the last ‘Beyond the Classroom Encounter’.

Opportunities for All Students

The opportunity to map can be made as simple or complex to fit the group. Those who may find mapping challenging, could instead just be asked to say what it is that they notice, or else a map template could be provided. If, for any reason, it is not possible to go outside into the grounds, the students can be asked to think what comes to mind about what they might notice.

Opportunities for Creativity

Students are asked to generate creatively their own categories which includes the possibility to re-think and be divergent about what might classically be considered a ‘category’. They might also be encouraged to ‘map’ the grounds using different media, possibly for example using found objects, where the students bring objects to a large map placed on the ground. Others might digitally map photographs of things identified. The activity also demands that students imagine themselves as another species which may require them to identify that they need to know more about the species and to think through where they might need to go to find this out.

Opportunities for Linking to Climate Justice

Key to this activity is that students explore planetary justice through a consideration of interspecies justice, whereby the focus is not just on the wellbeing of humans but of non-human species living alongside them. Addressing justice issues for nonhumans is about conservation and restoration of diverse ecosystems. At the same time, this requires attention to associated social justice issues that this might raise, with a consideration on the balance of impact on humans as well as nonhumans. It raises questions about which humans are expected to adapt (e.g. move, change livelihoods, etc.) and which groups are included in deliberations about what to do to ensure interspecies justice. The activity could be extended to think about their own grounds and to deliberate which humans have access to particular areas and on what basis (e.g. some student groups dominate certain sports or eating areas; adult only access to quiet or utility areas), as well cultural and aesthetic preferences (e.g. for mown lawns rather than rewilded areas) and risks of harm (e.g. insect bites, water, dangerous trees, poisonous plants). How might entitlement and access be rethought to achieve a balance between different human groups and multispecies groups? When students discuss the differences of what they include on their maps, this might also prompt a discussion of cultural diversity and interests of what is noticed and valued.

Visual Encounter

Visual Encounter

Picturing mammals past and present

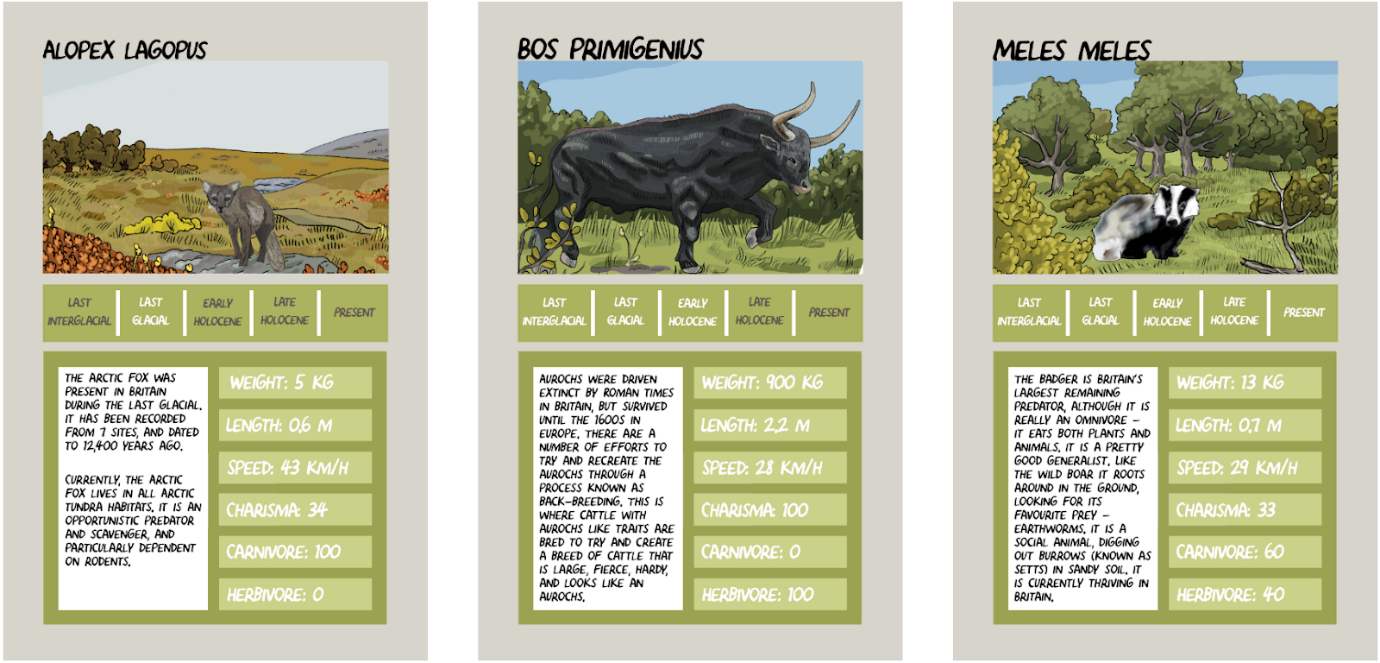

1. Have a look at the cards of Britain’s large mammals, past and present. Here are a few examples.

You can find the full list of cards for downloading here: https://rewildingsussex.org/projects/sussexs-past-and-present-megafauna/

- What do you notice? What interests you? What surprises you?

- Share your thoughts and observations with others.

- The cards are designed for a game of ‘Top Trumps’ that you might want to play. This is where you share out the cards, compare the numbers, and the person with the highest value wins.

- What other games might you play with these cards? Think about what other resources you would need to play a different type of game with the cards (e.g. multiple packs of the same cards to match cards in Snap, or the memory game Pelmanism).

- Design your own game to play with the cards that draws the players’ attention to the changes over thousands of years where some mammals have remained, and others have become extinct.

2. Read this short graphic short story of how Sussex has changed over the last 115,000 thousand years:

https://rewildingsussex.org/projects/through-the-backwards/

- In your group, create your own visualisation of one epoch. You will be given the epoch to describe, but don’t tell the other groups which one you have.

- A visualisation describes somewhere in a way that takes the audience to what you are describing. This might include the things you see, what you hear, smell, taste, as well as what you might think and feel.

- The visualisation must include one random thing that does not fit your epoch. This might be an animal, a plant, another natural feature, some technology, a smell or sound, or a thought or idea.

- When every group has completed writing their visualisation, take it in turns to read out to the others. Ask other students to do two things:

- Guess the epoch, giving their reasons why.

- Identify the one random thing you have included that does not fit the epoch. Ask them to say why.

- Did the other students also notice things that did not fit the epoch that your group hadn’t planned or noticed yourselves?

- Consider altogether why might things have changed across the three epochs. What might have been the role of humans and other factors in producing this change?

- Using the worksheet ‘Through the Bush Backwards’ explore in pairs how you feel about the landscape in the region where you live: how it could be improved? Think about what you would like to bring back from the past, and what you value now, to create your own vision for the future. The worksheet can be found on this webpage: https://rewildingsussex.org/projects/through-the-backwards/

Opportunities for Embracing Uncertainty

The uncertainty of this activity is in the variability of what students notice, and what they choose to draw others’ attention to. This includes through the games they select to play and those they design, as well as in their crafting of their visualisations of the epochs and the landscapes of where they live. A key role for the teacher is to challenge the students to think carefully about what it is that they desire, and the implications for themselves, other people and other species. This requires them to think beyond immediate pleasures and gratifications.

Opportunities for All Students

These activities can be made as simple or as complex as appropriate. For example, some students may take great pleasure in having the cards printed off, to look at and play with. This site offers helpful instructions on how to play Top Trumps: https://www.wikihow.com/Play-Top-Trumps#/Image:Play-Top-Trumps-Step-05.jpg.

Opportunities for Creativity

For all students, the activities are inherently creative and require them to imagine another time and place, as well as how to create a narrative that takes their audience with them. Some students may want to spend time with the cards, to integrate them into their own imaginary games, including within their play, conversations and stories, and/or to recreate them with junk modelling, clay or drawing, for example. Some may want to explore the incongruency of having animals from different epochs together in play or imagined conversation.

Opportunities for Linking to Climate Justice

This activity draws attention to how species have become extinct and raises the opportunity to consider the reasons why, including the role of humans, throughout history and in the current geological epoch described as the Anthropocene. Students may bring their cultural diversity into their own game design as well as into shaping what they select for their future. These differences would be a valuable topic to surface and explore with the students.

Deliberative Encounter

Deliberative Encounter

Messy deliberation

This activity invites you to consider this question: Is biodiversity too messy for the grounds around your building/s?

- Firstly, walk around the grounds of your building/s in pairs or small groups and identify the 3 to 5 areas with plants and animal species. You might include grassed areas, planted borders, vegetable patches, plants growing where they were not originally planted by humans (e.g. in between paving slabs, out of the sides of buildings, in guttering). For each of these areas, decide whether you consider them to be ‘messy’, ‘tidy’ or ‘neither’. Say why. Does everyone in your group agree or are there different opinions?

What other adjectives would you use to describe each area? Why?

If you were an animal species – such as a butterfly, bee, worm, hedgehog – what adjectives might you use to describe each of the areas, do you think? What would explain the difference between your own and the animals’ choice of adjectives?

- Now, in pairs or on your own, go and find somewhere to sit. Look carefully around you and notice what you can see close by. This might include the ground, plants, small insects, found things or made things, and any sounds or smells. Perhaps your area is busy/calm or noisy/quiet (whether this is made by humans, other species or things), and perhaps how you would describe your area changes over time. Create a short story that you could tell to others, taking inspiration from what you have noticed.

Come together and share your stories. What is similar or different about them?

Invite those listening to your story, to make links between your chosen area to sit in, and the story that you have created. Which creatures (human or other animals) or plants would be drawn to the area that informed your story? Why?

All together, discuss how all the different stories have been shaped by the areas in which they were created. Identify some of the key factors. Collectively, do your stories generate any recommendations for those responsible for looking after and planning the grounds of your building/s? What might need to stay the same and what might need to change? Who else might need to be involved in making some decisions about this?

Opportunities for Embracing Uncertainty

Within recent years, much has become known about the value of wilding to ensure greater biodiversity, although this presents challenges, especially for built environments designed to keep humans and nonhumans separate. It recognises the value of multiple perspectives when balancing human interests with those of other species.

Opportunities for All Students

Students can engage in as much or as little detail for each of these activities. Some may benefit from a more explicit playfulness and embodied engagement in the space, such as running, rolling, touching the environment, rather than simply sitting, and attending to it. The storytelling can also take many forms and, where appropriate, can be modelled and even done together with another person, such as an older student, a parent, or teacher.

Opportunities for Creativity

When telling their stories, the students might do this in a number of different ways. This could include audio recording, drama, comic strip, storyboard, etc. The stories can be done taking on and acting out the different roles together, such as that of the butterfly, or the grass or a tree. Those taking on different roles might enact what is it possible for them to do (i.e. a tree can’t move but a butterfly can fly around relatively freely), as well as to identify their respective experiences. For some, creating props and costumes might be key in engaging their interest, excitement and deep thinking.

Opportunities for Linking to Climate Justice

The Anthropocene has championed the command that humans have in containing nature. This activity is designed to examine whether it is possible and desirable to shift the balance to allow for greater biodiversity. It acknowledges and aims to surface the multiple and competing perspectives about whether, where and how to do so. These perspectives are informed by people’s cultural and classed identities and can become fraught with deep polarisations and moralisations. Rather than assuming any given perspective is correct, the activity seeks to explore how the students, their communities and other species might experience the grounds around the building, and the possibilities for something different to be done in how these are maintained.

Beyond the Classroom Encounter

Beyond the Classroom Encounter

Creating and using a seed disperser

1. Collecting seeds

You need to collect some seeds that you will then go on to disperse elsewhere in an appropriate area. Think where that area might be and consider these questions:

- Where do you have access to? This might be a private garden, a window box, an allotment, a park, a woodland, or patch of waste ground (from a crevice in the pavement or a larger area).

- Do you have permission to access this area? (Check with someone who knows if you are unsure)

Next, you need to think where you might access seeds to disperse. Again, consider these questions:

- What areas of land can you access, and do you have permission to access this area?

- How will you identify seeds on the types of plants that might grow in this area?

- What types of seeds might you find and at what time of year? You might include seeds from wildflowers, grasses, trees, shrubs, edible plants, etc.

- What part of the plant is it appropriate to pick?

- How might you carry and store the seeds?

When you are ready, go out and collect some seeds. Then try to identify the plants from which you have picked your seeds. How will you identify the plant species?

Now consider whether the collected seeds are appropriate to your chosen area:

- What will others think about the dispersal of your particular seeds? Who or what might be supportive, and who or what might not? Would there be benefits or challenges in asking what people think?

- How will the seed dispersal be experienced by existing plant and animal species?

- What might be some of the unforeseen consequences of dispersing your seeds in this area?

Are there some seeds that it would be better not to disperse in this area? What makes you think this?

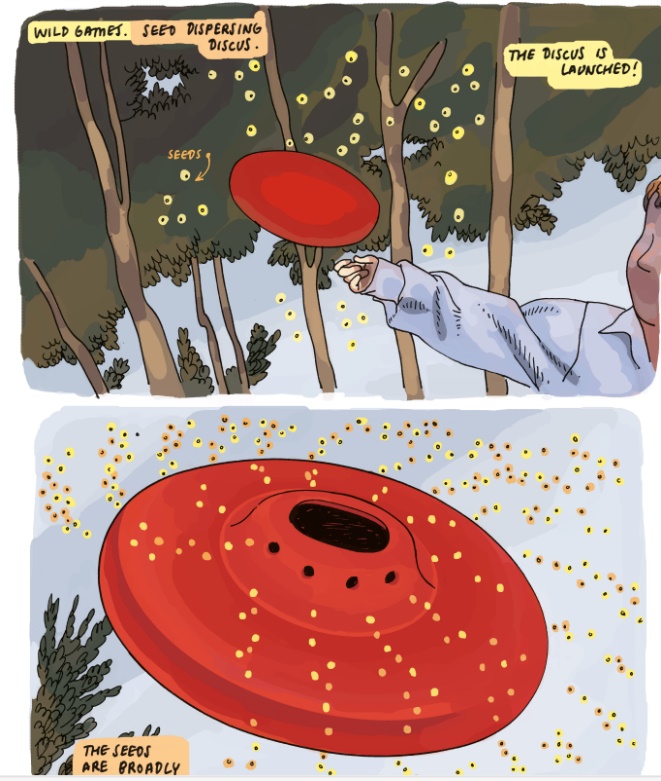

2. Making a seed disperser

Using the materials provided, design a contraption that can be used in a fun way to disperse the seeds that you have collected.

- How will you know that you have been successful in the design of your disperser? Think about what you know now and what you might have to wait to find out.

Consider the appropriateness of different materials for making your seed disperser:

- What things might you need to think about when deciding if they are appropriate?

- When planning your design, consider how nature disperses seeds by wind, water, fur, hooves, poo, etc. What can you learn from this?

Once you have made your disperser, go out to the area that you decided would be appropriate for seed dispersal.

Go out and use your seed disperser!

Opportunities for Embracing Uncertainty

Typical school curricula will guide students as to the processes and primary conditions for germination. However, the activities described here are designed to give experience of some of the uncertainties inherent in germination. There is the added uncertainty of what seeds students will find, which can lead to a discussion about how and why they have found different things. They might also consider what else they need to know to become more adept at locating and collecting seeds. Where students can work in groups, even if only for parts of the activity, this will help to generate richer deliberations and support them to identify solutions in response to the questions and challenges raised.

Opportunities for All Students

This activity can be used with a wide range of students, although they will engage in different ways and degrees, including in the sophistication of their disperser designs. Some students may need some initial input on what is a seed, and useful basic introduction can be found here: https://kids.britannica.com/kids/article/seed/399591.

Others, with deeper curricula knowledge, might consider what types of seeds would germinate in their chosen area, taking into consideration factors such as light, soil, exposure, etc. It is important for students to know the legal limitations of what it is they can pick and collect. In the UK, for example, this includes not uprooting wild plants without permission of the landowner/occupier, although the collection of seeds is allowed if not in a protected area. (You can find more information here: https://www.plantheritage.org.uk/conservation/conservation-cultivation-advice/plant-legislation/).

There are different online resources that can be used to identify plants, as well as resources available from libraries. A useful app, although it has a cost, is Picture This (see: https://www.picturethisai.com/). Here is a link to a useful website on making seed bombs for seed dispersal: https://www.wildlifetrusts.org/actions/how-make-seed-bomb

Opportunities for Creativity

The creativity of this activity is primarily in the students designing, making, and using their seed disperser. The types of materials that can be provided will vary depending on the student group, and the ambition of the design task, but might include junk modelling using cardboard containers; non-peat compost; clay; corn-based plastic; non-plastic sticky tape; and cornstarch packing. You might also include some non-biodegradable materials, including those made of different types of plastics, to open-up discussions about the appropriateness of their use for this task.

Opportunities for Linking to Climate Justice

The activity draws attention to the challenges for plants of seed dispersal and germination, and the role of the human in supporting this process. It also draws attention to how human intervention might not be appropriate and requires careful consideration. Thinking about how other people might respond to the seed dispersal needs the students to consider aspects of the built human environment, the challenges, and possible effects, of the subsequent roots and plant growth on those who live or work in or close to the area.

Perpetua Kirby, Christopher Sandom, and Rebecca Webb