Topic 11: Menstrual health

Brief Encounter

Brief Encounter

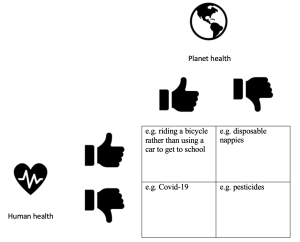

Healthy humans, healthy planet

-

-

What things are good for your health? What things are bad for your health?

Is there something that you cannot decide whether it is good or bad for you (for example, watching television)?

-

What things might be good for the health of the planet? What might be bad?

Is there something that you cannot decide whether it is good or bad for the planet (for example, recycling your soft plastic waste)?

-

In pairs, discuss whether you agree or not where each of the examples have been placed in the box below. You may disagree with where the examples have been placed and you can explain why.

-

-

Working in pairs, draw your own table similar to the one above. Add your own examples in each box. It may still be difficult to decide where each example fits.

-

Share and discuss your examples with the class.

Opportunities for Embracing Uncertainty

Uncertainty is core to this activity, as it is difficult to come to a position about whether or not something is healthy both for humans and the planet. Discussions need to focus on and explore specific contexts. For example, riding a bicycle is (arguably) good for the health of many humans (but not all); it is neutral for the planet although it has a positive benefit if it replaces carbon-fuelled transport (such as the car). Bicycles also use carbon to be produced; electric bikes have a greater carbon footprint than others, and their batteries rely on lithium mining which causes damage to land and water supplies, and can threaten biodiversity and displace communities.

Opportunities for All Students

Younger children can talk about what helps them and the planet to be healthy. In addition, the teacher can take on the role of calling out suggestions, with the children running to a different corner of the room to indicate what they think. Examples of things to call out include birthday cake, sausages, aeroplanes, shop-bought drinking water, buying clothes, Lego, firewood, pets, showering daily, eating vegetables.

Opportunities for Creativity

Students could draw a picture of themselves as healthy, and another of a healthy planet, and make visual links between the images. This activity particularly lends itself to use with younger children, who may find creating links in the boxes above more of a challenge. Taking the icons in the illustration as inspiration, the older children might create their own visual representation of how human-planet health is linked, either by creating a logo or else an image for each box, for example.

Opportunities for Linking to Climate Justice

This activity encourages students to think about ‘planetary justice’ that relates both to the planet and humans. It is also about how human health is not just about our own bodies but about relationships. It focuses on the relationship between what we do as humans, and its consequence for the planet, which in turn affects other humans – including future generations and those most vulnerable to the risks of climate change.

Visual Encounter

Visual Encounter

Zooming in on sanitary products

-

Look at the photograph and consider:

-

- What do you see?

- What do you think?

- What do you feel?

- What questions does it raise for you?

2. Some of the waste is menstrual products, including disposable tampons and pads.

About 800 million people menstruate each day. This is 26% of the global population.

Here are some key statistics for India, a large country, with a population of 1.4 billion people:

-

- 121 million women and girls use an average of eight disposable and non-compostable pads per month

- This adds to 1.021 billion pads monthly, 12.3 billion pads annually.

- This menstrual waste weighs 113, 000 metric tonnes annually.

Here are some key statistics for the United Kingdom, with a population of 68 million people:

- 15 million people menstruate in a year.

- 137,000 girls miss school due to a lack of access to menstrual products.

- They use 3.3 billion individual menstrual products a year.

There are different types of menstrual products, such as tampons, pads and menstrual cups.

Tampons and disposable pads are single-use products. Unlike food companies, menstrual products companies are not required to state the materials that make up their products. The two main materials are known to be cotton and, commonly, plastic. They also usually contain chemicals: regulations require these to be non-hazardous and in low concentration. There is some debate about whether the chemical levels are appropriate for use in or on the body. Tampons and pads without plastics and chemicals are more expensive to buy.

Menstrual cups are reusable products. They are made from silicone, which comes from a natural product called ‘silica’. Reusable menstrual pads are made of cloth and absorbable materials. Like menstrual cups, reusable pads can be washed and reused for years. Menstrual underwear, also known as ‘period pants’, are another reusable option.

Have a look at a range of menstrual products and think about the facts above.

- What stands out for you?

- What questions do you want to ask?

- What feelings are raised for you?

- What should be done? By whom?

Write your responses on a piece of paper, a board or sticky note, and place where all the group can see it and discuss it together.

3. In the UK:

- 222,000,000 tonnes of waste are produced a year.

- 27,000 tonnes of this waste are from menstrual products.

- 0.01% of all waste is therefore from menstrual products.

- 3,300 tonnes of menstrual products are flushed down the toilet.

In pairs, discuss what you think:

- Is 0.01% a lot or not? Why do you think so?

- If you do not live in the UK, how much menstrual waste do you think is produced in your country? More than the UK? Less than the UK? What makes you think so?

- Who and what is responsible for the pollution?

- What should be done? By whom?

Be ready to share your thoughts with others.

Opportunities for Embracing Uncertainty

This activity encourages students to think about the multiple possible factors that contribute to the polluting waste of sanitary products, that extend well beyond the individual person. It might include, for example, a lack of menstrual waste bins; the companies that make products out of plastic; the oil industry for producing plastics; governments for regulating products and waste; society for creating shame around menstruation that creates silence, limiting discussion and questioning. It also enables young people to identify their own questions and feelings in response to the ‘facts’ to do with human and planetary health.

Opportunities for All Students

This activity is aimed at students who are both pre-menarchal (onset of menstruation) and of menstrual age, but it is also designed for boys and people who do not menstruate. The activity requires the teacher to bring examples of menstrual products. Here is a useful site with illustrations of different products, which may be particularly useful if it is not possible to source some or all products: https://www.dreamstime.com/menstruation-set-elements-pads-tampons-menstrual-cup-other-feminine-hygiene-products-menstrual-calendar-female-menstruation-image155647745.

Further discussions on the history of menstrual wear can be explored, including a focus on the sustainability of menstrual products over time. Two useful UK sites include the V&A https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/a-brief-history-of-menstrual-products and the Science Museum: https://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/everyday-wonders/menstruation-and-modern-materials.

The annual and India figures are from this document: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/water/brief/menstrual-health-and-hygienethat

Opportunities for Creativity

Students can think of ways they could design their own menstrual product: what locally sourced or recycled materials would they use? They could draw a picture of their product or even create a prototype. What features would they choose to prioritise (e.g. comfort, attractive design, leak-proof, safety, environmental sustainability, etc.) and why?

Opportunities for Linking to Climate Justice

This activity further explores the link between human health and planetary health. Where it is safe to do so, this activity could be undertaken alongside a beach/street/rural walk to identify types of waste encountered with the purpose of a supervised litter collection. Alternatively, this activity could be undertaken alongside a walk to the nearest outlet that sells menstrual products: students could be asked to identify types of products available in their locality, the sustainability of the products and their packaging, the cost and the impact of product availability on menstruating people and the environment. They might deliberate the tensions in purchasing desirable products, as well as a consideration of how else these products are, or might become, available for reduced or no cost. They may have seen free products available in libraries, public toilets, etc., which might generate discussion on the desirability of this. Things they might wish to consider include affordability and inclusion, the range of products available for free, whether products in public places might also change public attitudes and perceptions of the shame of menstruation.

In the UK, tax was taken off menstrual products in 2021: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/tampon-tax-abolished-from-today. The students might also want to deliberate their views on this change, including reasons why tax might have been originally included and the effects of the reduced price of the products.

This accessible paper offers background information on the different things that constitute menstrual product pollution: https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ijgo.14311, and addresses issues of accessibility to menstrual products (sometimes known as ‘period poverty’) that includes details of country governments that have increased access in schools and/or public places (e.g. Scotland, New Zealand, France, Kenya, Uganda, Zambia). The paper highlights that whilst attention has been given to the social justice context for humans to have equity of access, nonetheless little attention has been given to the global and environmental impact of these products.

Deliberative Encounter

Deliberative Encounter

Expanding ideas of menstrual health

Menstrual health is defined as complete physical, mental, and social wellbeing in relation to the menstrual cycle.

- In a small group, identify 2 truths, 1 myth and 1 question about what supports the health and wellbeing of someone who menstruates, for each of the following:

-

- Physical

- Mental

- Social

First, share your truths and myths with the whole group. See if others can guess which is which.

Next, write your own group questions on a sheet of paper. Place your own sheet somewhere around the room. Everyone, staff and students, can now be invited to go around the room writing responses. This might be an answer, a suggestion, or a further question. Together, discuss what has asked and the responses. What more might you need to find out to answer the questions?

2. The definition of menstrual health does not include any reference to planetary health.

In your groups, design the packaging and/or a leaflet for a menstrual product that addresses physical, mental, social and planetary health. Include the images and text that you think might be helpful.

Once you have drafted your design and text, again put these around the room and invite others to comment.

3. There are people who are differently abled (living with a physical, mental or learning challenge) who menstruate.

What particular challenges with menstruation do you think they might experience? How can they be supported? How do you think products appropriate to their use can be designed?

Opportunities for Embracing Uncertainty

This activity offers an opportunity for students to explore knowledge about menstruation and how it is viewed and experienced diversely, as well as the varied possible implications for both the health of people and planet. The discussion might identify whether and how students (and teachers) can talk freely about menstruation or what prevents this. This offers the opportunity to discuss the possible reasons and its effects. A useful resource for teachers is Chella Quint’s Period Positive National Curriculum for England: https://periodpositive.com/period-positive-menstruation-education-programme-of-study/. This resource supports teachers with a language for menstruation education. The activity offers the opportunity to revisit the Brief Encounter, to consider how human and planetary health are interdependent.

Opportunities for All Students

This activity aims to explore the value of lifting menstrual taboo and stigma. It can explore historical and cultural perspectives, and current euphemisms, often associated with the shame of menstruation. This can be used as a prompt to discuss ways to enable inclusive and affirming language. It is an opportunity to include students who menstruate, as well as those who do not. The latter may include those who will never menstruate and those who come to menstruation later, and some may also experience anxiety in relation to their own body.

Opportunities for Creativity

In designing the packaging of their product, students might think about what features they want to emphasise, as well as the sustainability of the packaging. Some students might create a prototype of their product and/or packaging. In addition, they might think about how to advertise their product, and this would link well to the Topic 4 (Food Shopping), particularly the Visual Encounter and Encounters Beyond the Classroom, that focus on the art of persuasion and creating adverts. In thinking about the inclusive and affirmative messaging about menstruation, students might create a collage or a collection of the myths, truths and questions that can be used for further enquiry and reflection outside of this session.

Opportunities for Linking to Climate Justice

You can read more about the definition of menstrual health here: https://thecaseforher.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/MentrualHealth_defined.pdf. The definition was developed by 51 expert stakeholders from the Global Menstrual Collective in 2021 (You can read about this movement here: https://thecaseforher.com/blog/introducing-a-new-definition-of-menstrual-health/). This was then taken on by the World Health Organisation (WHO).

Students might want to deliberate why the WHO had omitted to define menstrual health previously and why they might have neglected this topic affecting half the world’s population. Be aware that there are many children who cannot access any or enough menstrual products and this can impact their health and their education. Some children seek to resolve this for themselves and their peers and there are many international organisations that address this.

Beyond the Classroom Encounter

Beyond the Classroom Encounter

Menstrual histories

Interview someone you know over 50 years old that you feel comfortable talking to. Ask them about their experience of menstruation over their lifetime.

Think what questions you might want to ask. Here are some example questions to get you started.

- What word/s did you use for menstruation in your lifetime?

- How did you learn about menstruation? Who told you and how?

- What were your personal experiences of menstruation when you were at school or in public?

- Did menstruation have any impact on your health:

- Physically?

- Mentally?

- Socially?

- Did you ever have difficulties accessing menstrual products? What were the effects and what might have been done to help you?

- Have you ever thought about the impact of menstruation products on the planet’s health? In what ways?

- In what ways did friends or family members support you during your menstruation?

- What advice would you give to young people about menstruation now?

Here are some example questions for those who never menstruated:

- What word/s did you use for menstruation in your lifetime?

- How did you learn about menstruation? Who told you and how?

- Did or does menstruation have an impact on the health of anyone you know:

- Physically?

- Mentally?

- Socially?

- What was that like for you?

- Have you ever thought about the impact of menstruation products on the planet’s health? In what ways?

- What advice would you give to young people about menstruation now?

- How do you, or can you, support people who menstruate?

Decide how you would like to share what you found out with others. Think about how their experiences might be valuable for those who are younger. You could draw, write, or use some other media.

Opportunities for Embracing Uncertainty

This activity embodies uncertainty. It is possible that the people approached (over 50 years old) may not feel comfortable talking about menstruation; they may lack the language to explain menstruation or various aspects of health such as mental and social health. Reassure the students that it is okay if older people do not feel comfortable speaking about menstruation. Reassure the students that they themselves may feel awkward speaking about menstrual health with older people to begin with and this is okay. Students can be encouraged to recognise that menstruation is a normal, healthy bodily process and it is okay to speak freely about it, but equally okay if they do not want to do so. This is an opportunity to model and explore together the ways in which it is okay to talk about menstruation in your particular context.

Opportunities for All Students

This exercise, in inviting inter-generational discussion, is an opportunity for students to consider the whole menstrual timeline, from pre-menarche to menopause. It is also an opportunity for non-menstruating students to consider the changes that happen in their bodies and hormones over time, and how their interdependencies with those who do menstruate. Students who are unable to find an adult over 50 to speak to about menstruation can have the same discussion with their teacher. The teacher could also help identify other members of staff and the community who are willing to speak with students. Some students will need more input than others to come up with their interview questions.

Opportunities for Creativity

The creative aspect of this activity comes through in identifying questions, creating the right environment for their interviewees to open up, including how to ask the questions and to demonstrate their openness to hearing the unknown and unforeseen responses. The students might also choose to feedback what it is that they hear through a creative written or visual presentation. This might include a poetic or visual artistic response, for example.

Opportunities for Linking to Climate Justice

This activity can be very revealing of differences in attitudes and language about menstruation between different generations, as well as across different groups including those of different genders, social class, ethnicities and cultures. This includes both for the students themselves and those they talk to. Students could explore these issues through, for example, creating their own ‘Guide to talking about menstruation’, thinking very carefully about their particular audience. Students might reflect both on their indebtedness, and the legacies, of those came before, as well as the students’ own indebtedness to future generations, with regard to the relationship between human and planetary health.