Chapter 12 – Undoing learning through lurking: a simple framework for supporting staff thinking about online teaching

Charlie Reis

We have gone through iterations of supporting online teaching since winter 2019. We are supporting staff with middle-term approaches and have solidified lessons learned into a longer-term approach and strategy for blended learning, using much of the same rationale people use when organising flipped learning. Although not a theoretical breakthrough, we have used our professional learning to devise a simple 3L (listening, learning, leveraging) approach for staff to combat student passivity – learning through lurking – online, as it is an issue for anyone teaching online, and lurking is a feature of both online behaviours and passive membership in community.

Introduction

Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University (XJTLU) is an English-medium of instruction (EMI), Sino-foreign joint venture located in Suzhou, China, which meant that we were teaching online in semester 2 of academic year 2019-2020 due to local regulations. The Educational Development Unit (EDU) of XJTLU immediately began to support online teaching, with a spectrum of workshops from pastoral care to running webinars to HyFlex teaching to how to design and structure VLE pages. Some of this was new, and some merely rethought for online teaching. What was not new, but more starkly visible since the online pivot, was the issue of being able to evaluate student learning online.

Our work focuses on enhancing the comfort and confidence of instructors with learning and teaching, and along with more staff development for how to teach online, we wanted to address participation and engagement online, which was not particularly well understood. As Ruthotto et. al., (2020) state, ‘[P]articipation in online settings, and particularly advanced degree settings, is neither well explored nor understood.’ The phrase ‘mental-state inference’ refers to a person inferring [judging] what another person is thinking (Ames, 2004). In online environments, there are fewer cues to make mental state inferences about student thinking or engagement. For example, if students are not using cameras, which can affect bandwidth, and instructors are not looking at student faces, much visual information about student behaviours is unavailable. Also, meeting software generally only allows for one microphone at a time to be broadcast, so there are fewer auditory cues.

XJTLU, being an EMI, is also aware that there are often language issues that texture student participation, which affects microphone use as it does textual chat participation; although possibly in different ways. Turning on a microphone to contribute gives one person voice, whereas multiple users can type into a chat simultaneously. Chat behaviors themselves are questionable; as preliminary data gathered by a statistician at XJTLU investigating chat participation at XJTLU has shown that a very small percentage of students are active in the chat. Rather than a bell curve showing normal Gaussian distribution, statistics from XJTLU show a ‘long-tail’ where the majority of students in text chats of online classes contribute little or nothing at all. It is usually a small group of students showing activity, while it remains unclear what the other students are doing out there in the ether.

Lurking

Cambridge University Press online dictionary (n.d.) defines lurking as ‘lying in wait’, and it generally has a negative connotation. Why are you lurking in the shadows? Hill (2013) identified four different types of learners in an open online learning community, specifically MOOCs:

- Lurkers: Enrol, just observe/sample a few items at most.

- Drop-Ins: Become partially/fully active participants for a select topic within the course, do not attempt to complete the entire course.

- Passive Participants: View course as content to consume, expect to be taught.

- Active Participants: Fully participate.

In an online context, lurking means spending time in a chat room or on a social media website, such as a conference room used for learning and teaching, and reading what other people are posting/saying without contributing anything yourself. Adjin-Tettey and Garman (2023) remark that lurking is being present online without leaving traces of opinions and feelings, and that lurking has been used as a derogatory term.

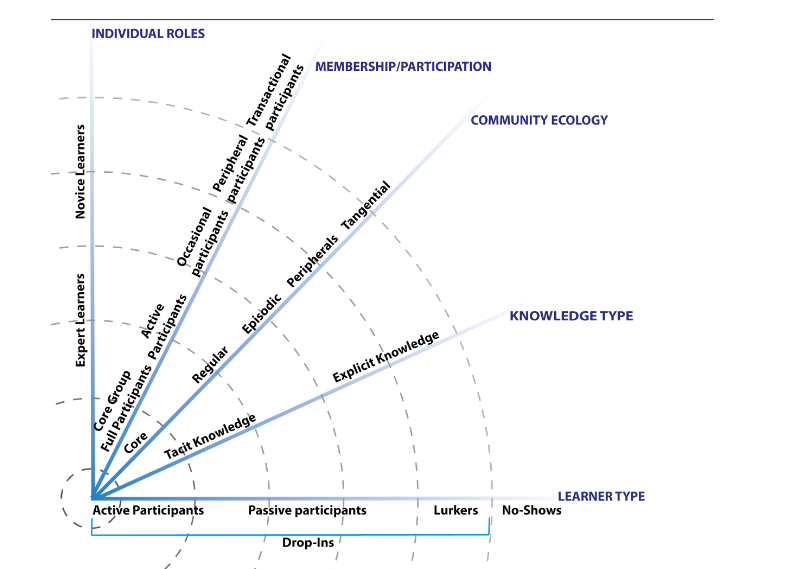

Some studies have characterised lurkers as free-riders, even suggesting that lurkers are undermining the sharing vital to online learning communities who benefit from the contributions of other students without generating any value themselves (Kollock & Smith, 1996; Morris & Ogan, 1996; Van Mierlo, 2014). Other studies present lurkers as still present and participating more as observers, and as a valuable form of online learning behaviour. Although quieter, lurking can still allow for deep engagement with both materials and discussions (Edelmann, 2013). Honeychurch et al. (2018) have visualised this well.

Because lurkers are mostly silent, we don’t actually know why they are engaging without overtly active behaviours, or if they are engaging at all. Possible reasons for lurking include difficulty with the language of the course, covering level of sophistication and decoding, a lack of confidence in being expressive, a desire to remain anonymous, introversion, lack of faith in their peers or in teacher-centred pedagogies, the distraction of the rest of the online world, as well as the fact that lurking is a normal part of online behaviour. As far back as 1991, Lave & Wegner were exploring ‘legitimate peripheral participation’, but for concerned instructors wanting information about how or if students are learning, lurking does not provide rich indications, such as evidence of cognitive presence. Moreover, for an instructor wishing to see how students are understanding or using concepts, or who has designed learning to be active, peripheral participation may be a less legitimate form of participation; certainly, it is less participatory.

Eleanor Shoreman-Ouimet (2021) presented an ‘I-3’ framework for engaging students in a large classroom to address student participation and engagement in learning about anthropogenic climate change in social science classrooms. The I-3s are ‘I’m here, I’m listening, I’m thinking’ and serve as students’ first concentrated interaction with a topic to provide the first step on a gradient towards higher-level mastery of material. What is appealing about the I-3 framework is the simplicity for students and staff, who are less likely to have thought out intricate pedagogies of online learning and teaching. We have altered the model as a framework, similar to Bloom’s Taxonomy (Bloom et al., 1956) but simplified for staff.

3-L Framework

Getting students to present/represent themselves online in a structured way in order to build greater interaction with content and peers makes a lot of sense for online learning for both student participation with content as well as making learning visible to the instructor so that in-action decisions about learning and teaching can be made. Thinking about undoing or preventing the behaviour of lurking, we propose a 3-L framework as a ‘gradient’ towards more sophisticated mental activity and cognitive engagement, made visible. It is not that the learning stage is the only stage where students are learning, but that the thinking skills presented are increasingly complex. The 3-Ls are listening, learning, and leveraging.

Listening

Listening is evidencing memory or recognition of content; this could be a quiz, poll or a student-generated question. Listening comes first as this is a most basic check of student engagement.

The idea at the foundational level of interaction is to get students responding and regurgitating to get used to the behaviours of engaged students who give energy back to a learning environment, which is a definition of engagement. Listening, as we have defined it, can be a measure of learning. It means that students can answer questions about content. However, recent debates about deeper learning indicate that this may reside at a surface-level of recall from short-term memory. Think about making this easy and anonymous to avoid certain issues with behaviours in pedagogical environments, for example a reticence to contribute.

One example from public health could be: What does Covid-19 stand for? What does the acronym mean?

Social science example: What is the difference between qualitative and qualitative data?

Literature example: Read a poem and explain your understanding of it.

PGCert example: Quality assurance (QA) stands for what? What types of QA procedures do we have?

Design example: List the properties of bamboo as a construction material.

Learning

Learning is evidencing deeper understanding of content; this could be a poll designed to dispel likely assumptions that are inaccurate, ordering of sequences or drawing mind maps. The idea here is to distinguish between memory and sense making in dealing with concepts. The idea behind the second L is to have students make knowledge coherent by seeing connections between more discrete bits and to avoid assumptions experts associate with erroneous common-sense understandings.

Learning as a subtopic of a schemata of learning may seem odd, but the idea is to get staff to create a structure where regurgitation of content is the not the definition of learning.

An example of 3-L learning for public health:

Choose the phrase that contains the most relevant information about how to stop the spread of Covid-19 from the options below.

A: Covid-19 contains RNA, is spherical in shape, and spiky in appearance.

B: Covid-19 spreads via droplets expelled from the mouth and nose of a person carrying the virus after coughing, sneezing or exhaling.

C: Covid-19 is thought to be zoonotic or transmitted originally from animals to humans.

D: Covid-19 has only been fatal for about 4.5% of people who contracted the virus in China.

While all of the statements about Covid-19 are potentially true, only one is valuable for understanding the importance of transmissibility. In this case, learning is about thinking about what is most significant, not just recalling information.

Social science example: Create a mind map about stresses on Qing Dynasty rulership.

Literature example: Explain how the protagonist of a novel interprets herself, and find textual evidence to support or contradict this.

PGCert example: Explain the difference between QA and QE with attention to the importance of benchmarks, particularly international, for our degrees.

Design example: Draw a force field analysis of bamboo as a construction material and give examples of real-world structures built of bamboo.

Leveraging

Leveraging is using core content to do something else that is student generated and directed in a more meaningful way than evidencing memory or basic understanding but that evidences learning outcomes, which could be case studies, research, projects, or simulations. Leveraging moves beyond making concepts coherent in themselves and asks students to do something generative with them.

Public health example: Use the public health advice from the WHO to create and present an infographic for a local community about the importance of the following in transmission prevention:

- Proximity

- Masks

- Ventilation

- Time

All are considerations in a variety of approaches to public health that the public needs to adopt in order to ‘defeat’ the virus when in public spaces where it could be transmitted.

If the former example is too focused on communication and lacking in disciplinary depth, students could be asked to use the following information to describe to a private biology lab what a Covid-19 vaccine should do:

- The current antigen used for vaccine development is the coronavirus spike protein, so named because it sits atop the spike of a coronavirus particle. This is the part of the virus that the immune system ‘remembers’.

- Vaccine-induced antibodies, made by the immune system against the spike protein, can prevent infection.

- Vaccines need to trigger the recipient’s immune response.

Both examples also reflect the belief that assessments and tasks should have relevance beyond the classroom or marking scheme of the course.

Social science example: Write a presentation, dialogue or ‘white paper’ about giving advice to a ruler during the Qing Dynasty, foreseeing questions about local historical conditions.

Literature example: Use two literary texts to compare presentations of the climate crisis, and make judgements about which seems more valid.

PGCert example: Come up with a proposal to make one specific QA/QE process more beneficial to students and staff, including background, existing policy or procedure, and stakeholders affected.

Design example: Build/design a bridge made of bamboo that can support a person weighing 100 kg.

Conclusion

The 3-L framework provides another tool to easily conceptualise and explain to students what types of behaviours we would like to see in online learning. A simple staircase of activity can show increased sophistication and autonomy in online learning.

References

Adjin-Tettey, T.D. and Garman, A. (2023), “Lurking as a mode of listening in social media: motivations-based typologies”, Digital Transformation and Society, 2(1), 11–26. https://doi-org-s.elink.xjtlu.edu.cn:443/10.1108/DTS-07-2022-0028

Ames, D. (2004). Inside the Mind Reader’s Tool Kit: Projection and Stereotyping in Mental State Inference. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(3), 340–353. http://www.columbia.edu/~da358/publications/ames_toolkit.pdf

Bloom, B.S., Engelhart, M.D., Furst, E.J., Hill, W.H., & Krathwohl, D.R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives, handbook I: Cognitive domain. New York, McKay

Bozkurt, A., Koutropoulos, A., Singh, A., & Honeychurch, S. (2019). On lurking: Multiple perspectives on lurking within an educational community. The Internet and Higher Education, 44: 100709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2019.100709

Cambridge University Press (n.d.). Lurk. Cambridge Dictionary [online]. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/lurk

Edelman, N. (2013). Reviewing the Definitions of ‘Lurkers’ and Some Implications for Online Research. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 16(9), 645-649. 10.1089/cyber.2012.0362

Hill, P. (2013, March 10). Emerging Student Patterns in MOOCs: A Graphical View. eLiterate. https://eliterate.us/emerging-student-patterns-in-moocs-a-revised-graphical-view/

Hosler, K, & Arend, B. (2013). Strategies and Principles to Develop Cognitive Presence in Online Discussions. In Akyol, Z. & Garrison, D. R. (Eds.), Educational Communities of Inquiry: Theoretical Framework, Research and Practice. (Information Science Reference: Hersey, PA), 148-167.

Honeychurch, S. Bozkurt, A. Singh, & L. Koutropoulos, A. (2018). Learners on the Periphery: Lurkers as Invisible Learners. European Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 20(1), 192-212. https://doi.org/10.1515/eurodl-2017-0012

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991) Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511815355

Ruthotto, I. Quintin Kreth, Q. Stevens, J., Trively, C., & Melkers, J. (2020). Lurking and participation in the virtual classroom: The effects of gender, race, and age among graduate students in computer science. Computers & Education, 151: 103854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.103854

Shoreman-Ouimet, E. (2021). It’s time to (climate) change the way we teach. Addressing anthropogenic climate change in social science classrooms. Learning and Teaching. 14(2), 76–86. doi: 10.3167/latiss.2021.140205

Bruff, D. (2020). Active Learning in Hybrid and Socially Distanced Classrooms Vanderbilt [online]. https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/2020/06/active-learning-in-hybrid-and-socially-distanced-classrooms/