Chapter 13 – Moving away from the traditional PowerPoint to an interactive documentary-style session

Dr Andrew Watson

Introduction

In 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic forced teaching to temporarily move away from the traditional face-to-face format. This resulted in practical difficulties, but also presented opportunities to develop new styles and embrace advances in technology. Practical STEM subjects were particularly hard-hit (Bacon & Peacock, 2021) with many subject areas relying heavily on field visits and laboratory sessions.

The limitation of narrated PowerPoint lectures

The suddenness of the switch to online pre-recorded lectures meant that traditional PowerPoint sessions which made up the core of teaching were often reused, but with a voice narration. It became apparent from interactions with students that they missed three main aspects of teaching:

-

Face-to-face contact

In a face-to face lecture, it is the presenter who brings the subject to life through the use of positive body language and gestures to emphasise key points and present enthusiasm (Bambaeeroo & Shockrpour, 2017). Being faced with a blank slide with a series of bullet points or images meant that students would regularly state that attention spans and enthusiasm levels had fallen.

-

Interaction within sessions

A key part of any face-to-face session is interaction, asking students their ideas, opinions and questioning them on the subject area. These aid learning through improved recall, understanding and analysis, but are also key in breaking up sessions through re-engagement (Almedia, 2012).

-

Lack of field visits

The use of regular field visits throughout the year formed the backbone of teaching. Removing these (during lockdown) was particularly detrimental to students who lacked a practical background in this area. The use of images within presentations aided this to some extent but was not a sufficient substitute.

The development of an interactive documentary style session

Throughout the 2020/21 and 2021/22 academic years, it was decided to completely redesign all pre-recorded lectures to address these three issues. A range of ideas were formed, tested, and revised based on discussions with students, these eventually evolved into an interactive documentary style session. This system could be adapted to benefit many other practical science subjects (e.g., biology, geography etc.).

-

Face to face contact

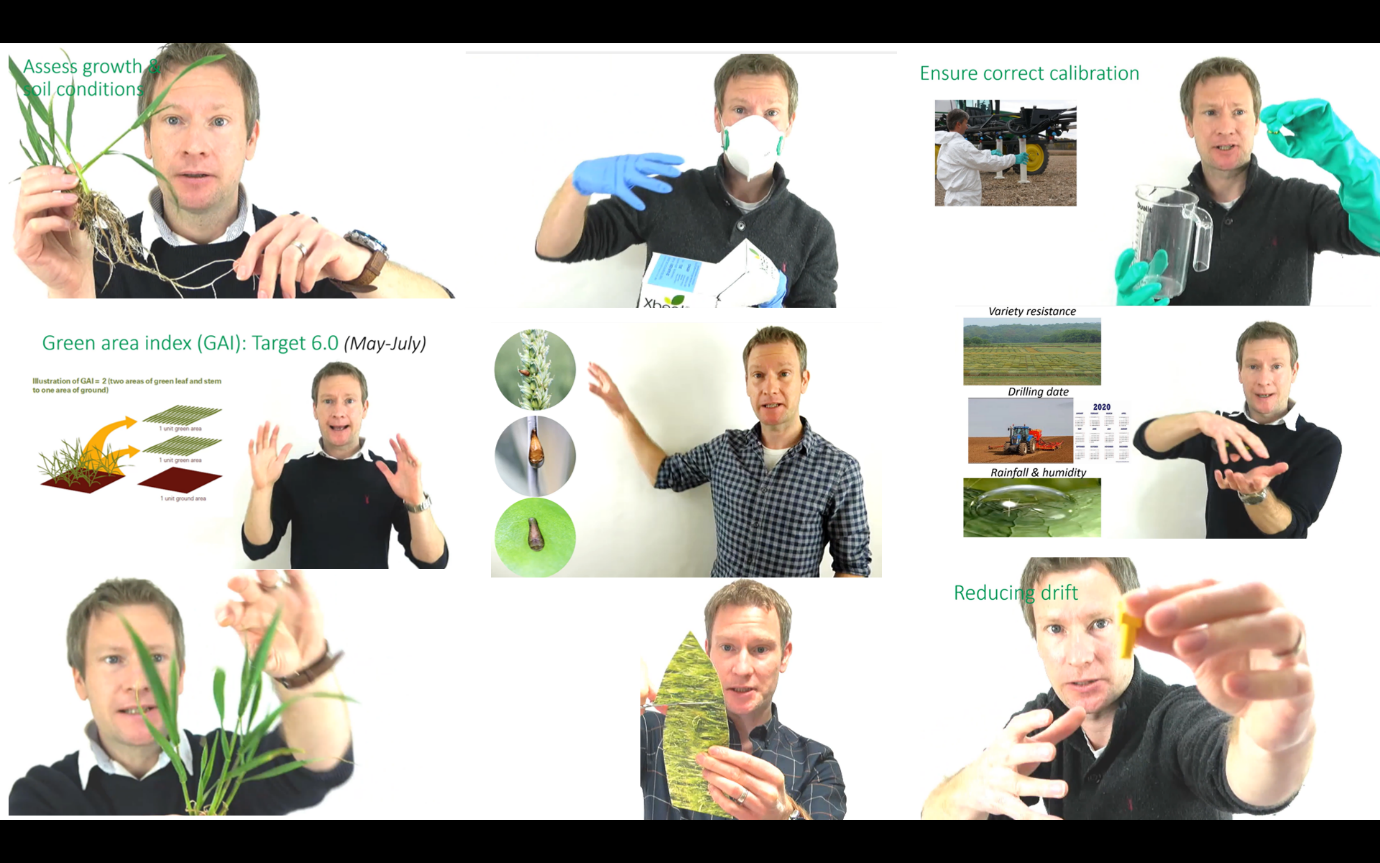

The presenter was videoed in front of a white screen and would speak into the camera as if speaking directly to the viewer. This helped project a greater level of enthusiasm into sessions through body language and created a style similar to that of a face-to-face lecture. This method also provided the ability to show examples/props (e.g., demonstrating safety equipment or field samples) as is often done in live sessions (see figure 1). Hand gestures could then be used to help explain or gesture towards key points. Feedback from students was overwhelmingly positive towards this approach, with 89% of 73 students stating that they preferred to see the tutor on screen as opposed to a narrated PowerPoint.

2. Interaction within sessions

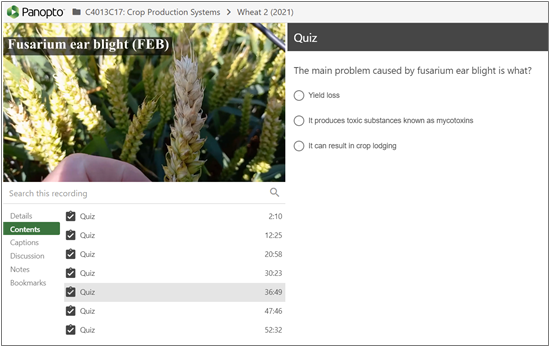

Throughout each session a series of questions were posed by the presenter at regular (approx. 5-10 minute) intervals (see Figure 2). Once the final version had been uploaded to the university platform (Panopto), multiple choice answers would then appear on the screen, so students had to interact with sessions to continue. From informal discussions with students in class, almost all (90.4%) preferred embedded questions, with around half also preferring to have a separate version without questions for revision purposes.

Students stated that the questions helped break up sessions and improved recall of key points. These results support the findings of Arnold and Barnett (2018). The level of student participation within these sessions was usually greater than in large face-to-face sessions within a lecture theatre, where many students feel uncomfortable answering questions.

3. Integration of virtual field walks and laboratory sessions

A series of crops and the management they received was closely monitored and filmed throughout 2020 and 2021. Short sessions were filmed as if presenting live field walks to a group of students, discussing the crops development and any notable points. These clips were then cut down, edited and merged into varying points through sessions so that management discussed could then be seen happening in the field. Relevant supporting text and graphs were embedded into these along with questions in the final Panopto version (see Figure 3). This proved to be particularly useful as it allowed students to see the whole production cycle taking place rather than a single point in time as seen in any individual face-face sessions. In the traditional academic year, many of the key production phases are missed as these often fall outside of term dates. Feedback showed 94.5% of students found the embedded field videos useful. Student feedback was overwhelmingly positive with many stating that they found it much more interesting than a traditional PowerPoint with bullet points and still images.

Conclusion

The student response to the interactive documentary style system has been overwhelmingly positive, showing that all three elements (tutor on screen, field videos and embedded questions) were perceived very positively by students.

This technique could be adapted into a wide range of subject areas, particularly those which involve a practical element (e.g., geography, biology and engineering). There is also the opportunity for students to create their own short videos using a smart phone to upload them into a shared space (e.g., shared OneDrive folder) to stimulate a greater level of discussion or for an alternative assessment strategy.

With sessions now having moved back to a face-to-face environment, several elements of this system have been transferred. Short field clips have been embedded throughout lectures to help bring sessions to life and improve student understanding and recall. Additionally, with some of the larger sessions held in lecture theatres, embedded questions using a phone app. are being used to help improve engagement without putting any individuals on the spot in front of a large audience. The response in the face-to-face lectures has been similar to that of the pre-recorded sessions which shows much of this can be transferred into live sessions.

References

Almedia, P. A. (2012). Can I ask a question? the importance of classroom questioning. Procedia – Social and Behavioural Sciences, 31, 634-638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.12.116

Arnold, L., & Barnett, S. (2018). Just ask – Locating effective teaching practice. Educational Developments, 19(2), 7-11. https://www.seda.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/publications_220_Educational-Developments-19.2-PDF.pdf

Bacon, K.L., & Peacock, J. (2021). Sudden challenges in teaching ecology and aligned disciplines during a global pandemic: Reflections on the rapid move online and perspectives on moving forward. Academic Practice in Ecology and Evolution, 11(8), 3551-3558. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.7090

Bambaeeroo, F., & Shockrpour, N. (2017). The impact of teacher’s non-verbal communication on success during teaching. Journal of Advances in Medical Education and Professionalism, 5(2), 51- 59.