Chapter 2 – Connection loss in online learning: a physiotherapy student’s experience of practical education during a pandemic

Dr Laura Blackburn; Dr Larissa Elisabeth Kempenaar ; and Dr Sivaramkumar Shanmugam

Abstract

Pandemic restrictions have presented many challenges for healthcare students and educators when transitioning from face-to-face to online practical learning. As restrictions will likely continue for the foreseeable future, there is a need for pedagogical approaches which place students and their experience at the centre of practical education. This chapter provides a student’s voice to inform developments in practical education.

Healthcare practical education involves an in-person, hands-on approach whereby students physically and verbally interact with each other and educators to develop psychomotor skills. The chapter discusses the impact on learning as a result of changes in the delivery of practical classes before, during, and after the pandemic. The chapter is divided into three methods of delivering teaching: face-to-face, online practical education, and hybrid. A final section evaluates experiences of peer learning, embodied learning, engagement, academic and professional socialisation, and assessment to inform recommendations for students and educators on effective practical education.

Introduction

Prior to March 2020, first-year physiotherapy students expected days filled with face-to-face contact with peers and lecturers (Ng et al., 2021). This described my experience when I enrolled in the Doctorate of Physiotherapy (DPT) pre-registration programme in January, two months before the first lockdown. Students in tutorials spent most waking hours in contact, developing close friendships. However, the fast-spreading coronavirus forced universities to close campuses and transfer all tutorials, including practicals, online. This sent many students into a panic, but we were not alone in our struggles to adjust to the new circumstances. Lecturers were forced to adapt their teaching to the requirements of distance learning, which presented challenges for practical, skills-based tutorials. Within a short period, we all had to adapt to alternative methods of learning.

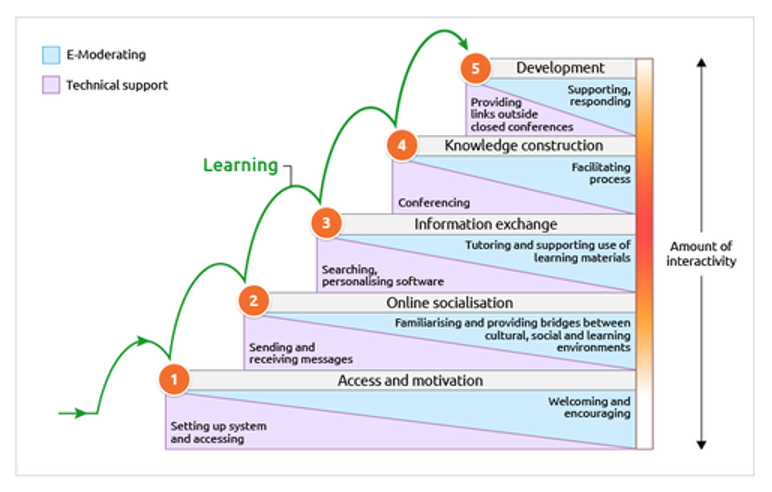

This chapter describes my learning experience over the pandemic, exploring the benefits and limitations of learning methods used over the first 16 months of my degree. The first three sections explore face-to-face, online practical education, and a hybrid of the two. Afterwards, I discuss student socialisation, embodied learning, peer learning, and assessment. My recommendations are based on student experience, complemented by Salmon’s (2013) five-stage learning and teaching model which positions the learning environment as essential to learner engagement. The DPT programme team adapted Salmon’s (2013) model to inform the learning and teaching principles for online and hybrid practical learning during the pandemic (see Figure 1).

Face-to-face learning

My previous degree involved didactic lectures, whereby students were passive participants in their learning (Zuckerman et al., 2020). I, therefore, felt somewhat ill-prepared for the flipped classroom approach used in the physiotherapy programme, a method described as an inversion of didactic methods (Hew & Lo, 2018). This involved practical tutorial preparation with reading and videos of knowledge, cognitive, psychomotor and affective skills. This allowed students to imagine performing skills and creating a mental ‘blueprint’, which was useful in the early stages of learning (Martineau, 2016). We then attended structured tutorials where we applied our learning practically with peers. Peer interactions outside of tutorials provided solidification of knowledge. I believe this approach promoted active participation in my learning.

In practical tutorials, the lecturer used their body movements to enable students to transition through the stages of psychomotor learning. For example, observing the lecturer allowed students to mimic all practical skill components, incorporating atunement to the socio-material of the clinical environment (Kelly et al., 2019). Students interacted in small groups, taking turns to act as models and practitioners for skills practice. However, at times, the intensity of the accelerated study load resulted in a lack of preparation for some students and a dependency on the lecturer to guide their learning. The lecturer facilitated discussion on clinical reasoning and sensory experiences, including visual, tactile, auditory and proprioceptive sensations encountered and how these might align with the reality of practice. The tutorial environment benefited from fluidity, whereby students freely moved from group to group. This allowed us to practise on various people with various body shapes and sizes and allowed us to experience the range of feedback that different individuals and their bodies provide. For example, when a therapist fully bends a patient’s knee, each individual has a different ‘end feel’ when the joint can bend no further. Our learning became embodied through integrating bodily movements and senses to develop our skills (ibid).

Connections lost in ‘practical’ learning

The pandemic struck five weeks into the programme and resulted in the suspension of face-to-face tutorials. In response, lecturers restructured the programme with the aid of Salmon’s (2013) five-stage model. As students on campus displayed behaviours consistent with motivation and peer and staff socialisation, the programme team assumed the social environment created on campus would automatically transfer online, allowing teaching to focus on stages three, ‘information exchange’, and four, ‘knowledge construction’.

Practical tutorials changed from having approximately 25 students in a room to online ‘practical’ seminars with 75 students. Social distancing and isolation together, with the transition to fully online, created a feeling of being stripped from my previous reality of life and learning. Anxiety and frustration filled student social media chats as we considered how and if the programme could achieve the quality of teaching and learning we experienced in those initial weeks. Some students voiced uncertainty about the practical nature of the course, and if we might still become the professionals that we had envisioned. Peer conversations raised questions about dropping out or taking a year off. Some students became concerned with personal safety, the welfare of their families, as well as options for travel home. I shared the concerns and experiences of my fellow students. However, on balance, the lockdown provided an opportunity to maximise learning and exam preparation. As a self-funded student, working in a private clinic and commuting daily to campus, lockdown freed hours usually spent travelling or with clients. My work-life balance improved as I had a healthier division between my studies and family time.

Despite these benefits, maintaining an environment conducive to active participation proved to be a major challenge. Few students seemed engaged in online seminars, with the same individuals speaking out. Silence became an accepted response to lecturers’ questions, and, at times, this resulted in lecturers using didactic teaching methods. The results of the online transition might have differed had the programme teams utilised the preparatory activities for ‘welcoming and encouraging’ described in the first stage of Salmon’s (2013) model, essential for student ‘motivation’. Although student socialisation occurred on campus, the polarisation of tutorial groups meant a lack of familiarity between students in the cohort. Some lecturers attempted to engage students by using ‘voluntold’ strategies and calling out random names from the register to answer questions. However, the unpredictability of this method led to some students admitting to experiencing feelings of vulnerability and anxiety. These feelings led to some feigning technical issues, diminishing stage three of the five-stage model. ‘Information exchange’ can be characterised by tutor-facilitated tasks, supported learning, and confidence building in preparation for the final two stages of the model: ‘knowledge construction’ and ‘development’. Other lecturers split the cohort into smaller groups for discussion, creating an environment with less exposure to enable student engagement. Unfortunately, the virtual learning environment randomly allocated students to groups, resulting in some students being with peers they did not know. Students, therefore, continued to largely be silent in these groups by not switching on cameras or microphones. This lead to a lack of integration of knowledge, skills, and behaviour for the final stage of ‘development’, related to practical skills.

Lecturers, as before, used a flipped classroom approach. Instead of demonstrations and practising skills, lecturers facilitated discussions of the pre-tutorial materials, employing case studies to enhance clinical decision-making for diagnosis and treatments. This allowed development in the ‘cognitive domain’ of learning, a prerequisite to applying practical physiotherapy skills (Krathwohl, 2002). However, students lacked opportunities to develop sensory experiences and progress motor learning. Students living with others on the programme could practise their skills on each other while respecting pandemic guidelines. Those who lived alone or with family relied on ‘mental imagery’, soft toys or family members for practice. For many, the disconnection of psychomotor and cognitive learning resulted in reduced skill development and a feeling of unpreparedness for practice. However, studying in isolation, I found my level of anxiety decreased without the constant comparison of myself to other students. I noticed that consolidation of new information required longer time and effort due to the nature of studying alone. Relying on myself, I made self-monitoring tools to evaluate my learning needs as I did not have a lecturer or peer feedback to guide me. Online learning afforded me the time to find methods most suited to my own needs and develop agency. Reduced anxiety, due to a lack of constant self-comparison, along with the time to apply the best-suited learning approaches, developed my self-assessment skills, enhanced my agency, and allowed a deeper level of learning.

Applying my learning in summative assessments, I answered questions related to case studies in an online video assessment. The online environment changed from pre-pandemic assessments with interaction between student, model and examiner. In contrast to previous assessments, which evaluated all learning domains, the online summative assessments focused on cognitive learning. We relied on our imagination and communication skills to verbalise practical skills, from bedside manners; hygiene protocols; to hand and body placement and a joint’s expected end-feel. Communicating this proved difficult due to the lack of physical and visual cues typical during face-to-face assessments, serving as reminders of the different aspects of skill practice. For example, seeing a patient on a plinth reminds us to adjust the height of the plinth to practise safely. We all passed our online assessments. However, we still lacked confidence in our unassessed hands-on abilities.

Hybrid practical learning

One year later, the return to limited in-person tutorials marked progress towards a pre-pandemic experience. Understandably, students had COVID-19 concerns, which were reduced by social distancing and donning personal protective equipment. As the university could accommodate limited on-campus hours, lecturers introduced hybrid teaching, supplementing face-to-face with online teaching.

Compared to pre-pandemic practicals, the classroom environment had changed. Demonstrations by lecturers became a rare occurrence, replaced by skills videos displayed on screens. Reducing the spread of the virus involved separating students into groups of three, called ‘bubbles’. In bubbles, we tried our hand at skills, each taking a turn to play the practitioner and model. Facilitating consolidation, lecturers were available for questions at bubble level. Feedback to the student practitioner targeted sensory experiences. Nonetheless, the rigidity of the bubble system limited embodied learning experiences to only two students.

While in-person tutorials enabled students to develop psychomotor skills, online seminars addressed the cognitive domain of learning (Krathwohl, 2002). In practice, cognitive, affective, and psychomotor skills come together when working with patients. Students seemed to miss their pre-pandemic integration of cognition and psychomotor learning during practical tutorials. Previously, students refined and consolidated this integration during out-of-tutorial hours in practical rooms. This informal, unstructured peer learning is crucial to practitioner development. Regulations and the Scottish weather limited this process, leaving students unable to meet inside or out. As a result, we lost the opportunity to consolidate our practical skills.

Limitations aside, hybrid approaches offer advantages over the singular use of online and face-to-face tutorials. For example, the flexibility of online delivery allowed attendance at seminars from anywhere, reducing the time and cost associated with commuting. Hybrid approaches facilitated sustained access through seminar recordings. Students became more able to maintain work and family commitments and attend tutorials while in self-isolation. Furthermore, the inherent flexibility of hybrid approaches and refocusing of priorities promoted equity and enhanced students’ learning and well-being.

Discussion

It is a major challenge to be accepted onto the programme, due to the large number of applicants, small number of places, and high entry criteria. Pre-pandemic students engaged intensely with practical modules perceived as core to their professional future. The lack of engagement online illustrated the extent of disruption experienced by students. Practical skills, central to the physiotherapy profession and identity, no longer informed embodied learning. The move to online-only delivery was a necessary response to circumstances, which reduced student engagement and impacted the learning experience. Lecturers’ efforts to increase engagement through socialisation in small discussion groups were not well received, as group activities were cognitively challenging rather than facilitating affective development. However, it is possible that the use of a bubble approach, as utilised in hybrid learning, may have facilitated progress, as reflected in Salmon’s (2013) stage two, ‘online socialisation’, and as a consequence, the latter three stages.

The five-stage model offers some explanation for reduced online student engagement. While students socialised in a face-to-face setting, this socialisation did not transfer to the online environment. Initial efforts appeared directed towards delivering content rather than revisiting the socialisation process. Students regressed in interactivity and engagement. Consequently, students did not transition to stage four; a more team-oriented, complex, collaborative interaction, as they did in face-to-face tutorials. In hindsight, a greater focus on the second stage, using bonding activities for bubbles, may have changed the ‘knowledge construction’ and ‘development’ outcomes in online learning.

Recommendations for socialisation:

- Prepare staff and students to use hybrid or online approaches by building on existing social structures. Or include resources with explicit approaches to socialisation.

- Prepare staff for interactions between students and between students and staff necessary for targeting aspects of well-being and self-care.

- Educational developers should provide resources to promote strategies for supporting online communities and fostering a sense of belonging.

The hybrid approach allowed practical skill development through cognitive, psychomotor, and affective learning domains, as in pre-pandemic tutorials. ‘Bubbles’ limited practice to group members, with students missing opportunities to learn from different individuals. Learning became disconnected, with affective, cognitive, and psychomotor elements covered separately, reducing student perceptions of competency in clinical skills, reasoning, and judgement. Restrictions impacted learning by making peer contact outside of tutorials nearly impossible. Lack of peer interaction and learning outside of tutorials continued to reduce opportunities to consolidate and reconnect learning.

Recommendations for reconnection of learning domains:

- Preparing staff to dedicate physical space and time to integrate learning domains requires both unstructured peer learning and structured, facilitated tutorials.

- Staff training should include the principles of mental practice and imagery in teaching approaches.

- Provide staff and student resources on using recording software to capture audio-visual practical skills to aid student self- and peer -assessment.

Assessments for hybrid modules varied, with some online and others in-person. Face-to-face practical assessments did not assess psychomotor skills on human models. Instead, as when online, the student described the application of a skill step-by-step. Although the in-person environment brought us physically closer, masks created an impersonal and foreign atmosphere, stripping warmth offered through facial expressions by assessors. The real benefit was that the student was able to use their full body and person to show exercises to the assessor. However, without the use of a model patient, the assessment did not reflect learning in all domains.

Recommendation for future practical assessments:

- Provide staff and student resources to realign assessment with digital pedagogical approaches, effectively promoting psychomotor skills. For example, students record themselves demonstrating skills on family members, using the authentic home environment.

Many students had little hands-on patient experience before beginning the programme. With the reduction of skills practice during the pandemic, students experienced higher anxiety levels and imposter syndrome as they embarked on their first placement. Consequently, some students required more than typical support and guidance from practice educators in developing psychomotor skills. Nonetheless, with time, determination, and support from academic staff and placement educators, the students of my cohort developed their learning on par with previous graduates while on clinical placement.

While the pandemic necessitated a crisis response to change teaching, it provided a unique opportunity to reimagine practical skills education. It is possible to envision a future where hybrid learning enhances face-to-face teaching. Without restrictions, students can benefit from traditional classroom approaches and peer learning, while hybrid learning approaches offer high levels of flexibility and accessibility.

References

Andrade, H.L. (2019, August 27). A critical review of research on student self-assessment. Frontiers in Education, 4, Article 87. Frontiers Media SA. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2019.00087

Hew, K.F., & Lo, C.K. (2018). Flipped classroom improves student learning in health professions education: a meta-analysis. BMC Medical Education, 18(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1144-z

Kelly, M., Ellaway, R., Scherpbier, A., King, N., & Dornan, T. (2019). Body pedagogics: embodied learning for the health professions. Medical Education, 53(10), 967-977. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13916.

Krathwohl, D.R., (2002). A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy: an overview. Theory Into Practice, 41(4), 212-218. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4104_2

Martineau, B. (2016). The influence of peers on medical students learning of psychomotor skills necessary for physical examination. [Doctoral thesis, Erasmus University of Rotterdam]. https://pure.eur.nl/en/publications/the-influence-of-peers-on-medical-students-learning-of-psychomoto

Ng, L., Seow, K.C., MacDonald, L., Correia, C., Reubenson, A., Gardner, P., Spence, A.L., Bunzli, S., & De Oliveira, B.I.R. (2021). eLearning in physical therapy: lessons learned from transitioning a professional education program to full eLearning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Physical Therapy, 101(4), Article pzab082. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzab082

Salmon, G. (2013). E-tivities: The key to active online learning. Routledge.

Zuckerman, S.E., Weisberg, R.B., Silberbogen, A.K., & Topor, D.R. (2020). A national survey on didactic curricula in psychology internship training programs. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 14(3), 193-199. https://doi.org/10.1037/tep0000279