Chapter 6 – Zoom-based negotiation: a path to tacit understanding. Scaffolding employability within the undergraduate curriculum

Rebecca A Payne and Joe Bramall

A business student’s ability to negotiate in a commercial context is not only a relevant building block within their learning journey, it augments their ability to leverage the best graduate job offers at the end of their studies.

There are two essential elements that make up the skill-set of a ‘good’ negotiator. They are job knowledge and personal skill. When we send students out onto industrial placement for a year, all of the stakeholders within the process are convinced of the long-term benefits of that investment. From the perspective of the student, it enhances employability, the university seeks relevance and impact and the employer auditions (and learns from) the latest talent about to present themselves to the job market.

Personal skill is different. We accept that the world contains ‘natural salespeople’ and ‘confident speakers’ but these, like negotiation, can be repeated and learned if we provide enough ‘space’ in the curriculum for this to happen. To shift students along the pathway from unconscious incompetence to unconscious competence (as explored by Cannon et al., 2014) we need to design in opportunities to practice with purpose.

Joe (student) says:

My decision to join Harper Adams was heavily influenced by the university’s close ties to industry and the compulsory placement year. Earlier in my education I certainly found myself asking the question ‘How will this help my career?’ and I know I wasn’t alone thinking that. This module was a great way to practice taught skills, sometimes this is missing from more traditionally run modules.

Although I will be the first person to admit that I thrive more in a coursework-based environment than an exam environment, I believe that the way that the negotiation was taught will stay with students more so than just regurgitating taught material for an exam. Whilst not perfect, the way the sessions ran supported me to develop my skills and more importantly, feel confident to use them all this time later.

Lockdown provided an opportunity to move pedagogy along at pace

Face-to-Face negotiation skills had traditionally been taught using ‘explain theory – develop understanding – apply to scenarios – reflect and repeat’ structures…. This approach (when contributing just 25% to module learning outcomes) was resource heavy.

As a busy lecturer, endlessly re-writing negotiation scenarios for students to practise then withholding the ‘best one’ for the live role-play assessment scenario had the unforeseen consequence of ‘weaponising’ the learning event. This element (only 25% of module grade) became burdensome for teaching staff, stressful and inequitable for students, and less aligned to professional practice than was originally intended. This was partially fixed by the introduction of a commercial resource called Negotiation Cards (The Negotiation Club Ltd, 2018). Three decks of cards, increasing levels of complexity and a four-minute timer offered students an opportunity to develop their negotiation muscles in short ‘reps and sets’ based around different concepts (tactics, observation, recording, multiple variables), facilitating growth and stretch in skill as it occurred. So we had progressed to engaging, successful, relevant experiences and were meeting learning outcomes in an innovative yet real-world way (the cards were at that time been used exclusively for professional courses in industry and within negotiation clubs which functioned like debating societies).

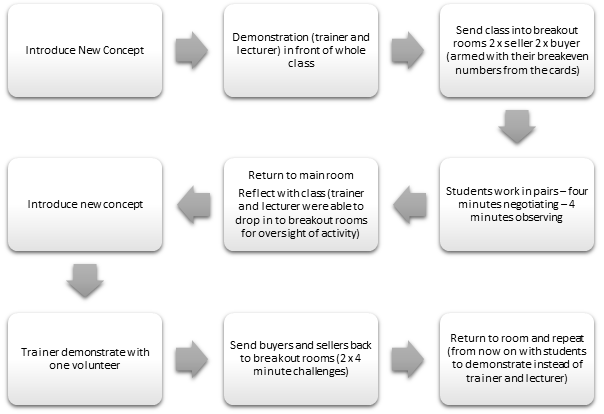

The pandemic removed multiple face-to-face sessions from the timetable. The negotiation card business owner had never run training sessions online before, but we brokered a deal where he would facilitate the sessions on ZOOM with all forty students. Each session would last 90 minutes. Each session would involve all students using breakout rooms to practice in groups of four (two sellers and buyers taking it in turns – one pair negotiating one observing). Each week (for four weeks) the bar would be raised, new concepts introduced and variables deployed, in a ninety-minute session there were six opportunities to breakout and practice your reps (see process map Fig. 1)

Joe says:

The pandemic has been a catalyst for changes in teaching and learning, and Zoom Negotiation was a great example of this. The structure was completely new to all of us and it understandably took time for everyone to grow in confidence and engage more. Engagement through the pandemic has been poor especially once Zoom fatigue kicked in. The entire atmosphere of the Zoom negotiation was like no other online tutorial I’d experienced. The anticipation of being thrown into a room to negotiate with anyone on your course, multiple times during the session helped many of the class remain engaged for the 90 minutes. The anticipation of getting selected to complete a negotiation with Phil (the negotiation trainer) kept us on our toes and I was focused on learning from others as I observed these interactions.

I think the fact this type of structure worked shows that trying a new way of teaching without months and even years of consultation can work well. This has been proven not only with this structure, but with the whole way students seem to be taught. There has been seismic change at university with online lectures now working well, and whilst not everything new works perfectly, the shift in attitude to trial new ideas at a faster pace is a way of standing out from the rest and offers the best opportunity to students.

While I enjoyed the 90-minute sessions I think being able to have a brief introduction in the form of an online video before the session, recapping last week’s session, would allow for more time to ensure a student has understood and remembered what has been taught at your own pace, something that students have been getting more used to. I think that would further support my tacit understanding of negotiation.

Why have I continued with the online model now we have returned to face-to-face?

In this instance technology removed barriers to learning in an obvious and powerful way. As we all became video call aficionados within weeks of lockdown, the social pressures often associated with in-person pairings in class were removed in a moment and replaced by a slick and engaging way of working that would be hard to replicate in the classroom. By this I mean the selection and sending of pairs of negotiators and observers into private breakout rooms, where the teacher can pop in to observe planned and clear tasks being performed, removed much of the large class performance anxiety. Additionally, built-in expectations around peer observation by the second pair in the room meant each four-minute exchange leveraged myriad opportunities for learning.

I can hear echoes of chairs scraping and sotto voce muttering as students moved into position to negotiate in previous years. This has now been replaced with:

- A relatively cheaply resourced training system that comes with real-world credibility and a built-in methodology for engagement in the classroom

- Swift and consistent allocation of buyer/seller roles each week (by editing your name on screen as you enter the Zoom class – so for the duration you are ‘BUYER – Fred’ or ‘SELLER – Susan’).

- Two teachers (external trainer and lecturer or lecturer and teaching assistant) mean one is addressing the class and setting up the next concept, whilst the second is running the back-office room allocations – keeping learning moving at a pace

- Breakout room entry is instantaneous and exit is simultaneous (no lagging behind in the breakout as it’s ‘shut’ from the teacher’s desk)

- Observation can be swift and non-intrusive – popping in to a breakout room (students are pre-warned) and leaving again without interrupting flow

Logistically this Zoom-based approach to pairing and small group practice makes sense, but beyond that the real value is the opportunity for students to observe each other’s micro gestures on video. Watching an unrehearsed ‘flinch’ as an offer takes you beyond the Zone of Potential Agreement (ZOPA) or attempting to mask the pleasure (relief) that you feel once the deal is struck, would be difficult to consistently generate in a classroom where there are 36 others beyond your table to inhibit your engagement.

Joe says:

One thing I did notice in the online sessions was the benefit of random pairing of people into breakout rooms. I am always happy to speak up in class but I know a lot of my peers are less comfortable to do this. This smaller breakout room format put me in with people I would otherwise not have spoken much to on my course. This mix of engagement is something that is quite rare in a normal classroom environment, and I think offers more opportunities to more of the class.

As for assessment…

Students were encouraged to broker their own sets of four for their assessed negotiation and meet online via Teams or Zoom. Some students chose to record the steps taken and the responses they offered as a narrative that mapped their progress toward the Zone of Potential Agreement. This gave an opportunity to reflect on what they might do differently next time. Peer reflection is also possible in this ‘safe space’ and, once submitted to an ePortfolio, allows the assessor to be a real fly on the wall of the experience and offer richer feedback.

Joe says:

The way of recording progress within an ePortfolio was still relatively new to me and others however, I found it an innovative way of being able to demonstrate what had been learnt. I have found it useful to go back to and read my reflection from the time. If I could do it again, I would document it more as a diary so I could carry on improving and developing my skills as opposed to just negotiating that one time. I have found that not only on placement, but my entire life revolves around negotiation and being able to further recognise and improve my weakness is a nice way to carry on the development of my skill.

The ability to record lectures has revolutionised the way I take in information with the ability to alter pace and even re-watch lectures. The same was the case with the ability to record our negotiations which allowed a more detailed reflection of performance again furthering the ability to develop my skills. To get a better insight into my skill development some kind of peer-to-peer negotiation scoring system might be a way to show progression? While negotiation is quite a subjective skill to measure, a scoring matrix may help support student personal development and help them recognise their journey towards unconscious competence.

I have had students tell me that they negotiated a deal on their next car because they felt confident enough to do so, others tell me they used their new skills within days of arriving on placement. Best of all was a dad at an open day who recognised one of the students in my presentation video – and sidled up to me after the event to tell me he regularly negotiated with that student (two years after graduating) and had wondered how he had become so proficient so quickly….

References

Cannon, H. M., Feinstein, A. H., & Friesen, D. P. (2014). Managing complexity: Applying the conscious-competence model to experiential learning. Developments in Business Simulation and Experiential Learning: Proceedings of the Annual ABSEL Conference, 37(2010), 172-182. https://absel-ojs-ttu.tdl.org/absel/index.php/absel/article/view/306