Chapter 8 – Covid-19 lockdowns: a catalyst for rethinking assessments in skill-based nursing courses

Dr Zeenar Salim; Dr Anil Khamis; Shanaz Cassum; Zohra Kurji; and Professor Pammla Petrucka

Amid the Covid-19 mandated lockdowns, the Aga Khan University School of Nursing and Midwifery in Pakistan (SoNAM-PK) closed their physical campuses to adhere to public health requirements for social distancing. The students living on campus returned to their primary residences. Students, especially in remote areas of northern Pakistan, lacked dependable internet connections and travelled miles to reach a central hub where internet connections were made available for the students by the university through a partnership with Aga Khan Development Network schools. While male students could travel on their own, female students required a male escort or stayed home and missed the lessons – in alignment with cultural norms and restricted mobility (Cassum et al. 2024). A few students captured and shared videos to exhibit their struggles to access internet connections and technological devices to the faculty and the university at large through social media, including Facebook and WhatsApp. Faculty at the school quickly pivoted instruction from face-to-face to the online medium, often without sufficient preparation. Around 30% of the SoNAM-PK faculty had experienced teaching in a blended modality; however, assessing students online was new for everyone. Aligning with the book’s theme, only assessments of the practice-based courses are discussed.

Initially, SoNAM-PK faculty focused on equity in teaching online, given the reality that some students had access to the internet, while others did not. The design and implementation of assessments were afterthoughts as the semester progressed and the likelihood of returning to in-person assessment dissipated. Initially, the plan was to replace paper-based examinations with online ones administered with video camera-based proctoring to mitigate cheating and academic misconduct. However, given the inequitable access to the internet by faculty and students, it became apparent that such a surveilled approach would not be possible. The need to adapt the design and implementation of the assessments in line with students’ access (or lack of access) to the internet was apparent.

SoNAM-PK leadership conducted a needs assessment to understand how faculty could be best supported. Nearly 40% of faculty were apprehensive about switching to online assessment, while 26% of faculty expressed that they were ill-equipped to handle educational technology and to troubleshoot issues related to technology in assessments. The faculty’s primary concern was how to assess students’ learning of practical skills in nursing courses, such as bedside patient management, counselling, patient education, measuring blood pressure, and administering vaccines. They feared that the assessments’ authenticity, validity, and reliability of assessments would be challenged as the students would not perform these skills in the clinics. Although it was difficult to assess the students’ learning in general, faculty reported that it was relatively easier to assess theoretical knowledge online compared to cognitive and psychomotor skills.

The Network of Quality Teaching and Learning (QTL_net) – a central unit at Aga Khan University – provides ongoing professional development for faculty in pedagogy and curriculum, as well as uptake and application of technology-enhanced instruction through short courses, workshops, one-to-one consultations, and mentorship. During the Covid-19 pandemic, QTL_net supported faculty to transition from a face-to-face to an online medium through instructional skills workshops and technological boot camps. Upon SoNAM-PK’s request, QTL_net educational development staff jointly developed a workshop on online assessment with a nursing faculty at the University of Saskatchewan, and teaching champions from SoNAM-PK, and faculty members from the education school. The workshop supported faculty in rethinking the purpose and design of approaches to conduct authentic, fair, and equitable assessments aligned with the predefined learning outcomes. The workshop was conducted online, and 40 (out of 45) nursing faculty participated from their respective locations (Rizvi et al., 2022). During the workshop, the faculty discussed assessments for the students in light of Walker’s principles of online assessment (Walker, 2007). They highlighted the necessity for adapting assessments based on internet accessibility aligning with three different student scenarios: no internet connection, 2G mobile-based, and 3G internet connection. During the discussion, various assessment tools were identified, including presentations, virtual labs, quizzes, podcasts, vodcasts, open-book exams, online viva exams, and online discussion forums; and question types, such as concept maps, scenario-based questions, case-based questions, online discussion boards, text-based debate, argumentative paper, reflections, problem-solving exercises, posters, multiple-choice questions, true/false, matching/ordering activities, and short answers. Subsequently, faculty, within their course teams, discussed the adaptations of student assessments for the three student scenarios.

Post-workshop, the SoNAM-PK curriculum committee required faculty to present their revised assessments and feedback was provided on the assessment alignment with the learning outcomes. After receiving and addressing the feedback, faculty members implemented the assessments to gauge students’ learning. For example, a faculty member narrates her experience as:

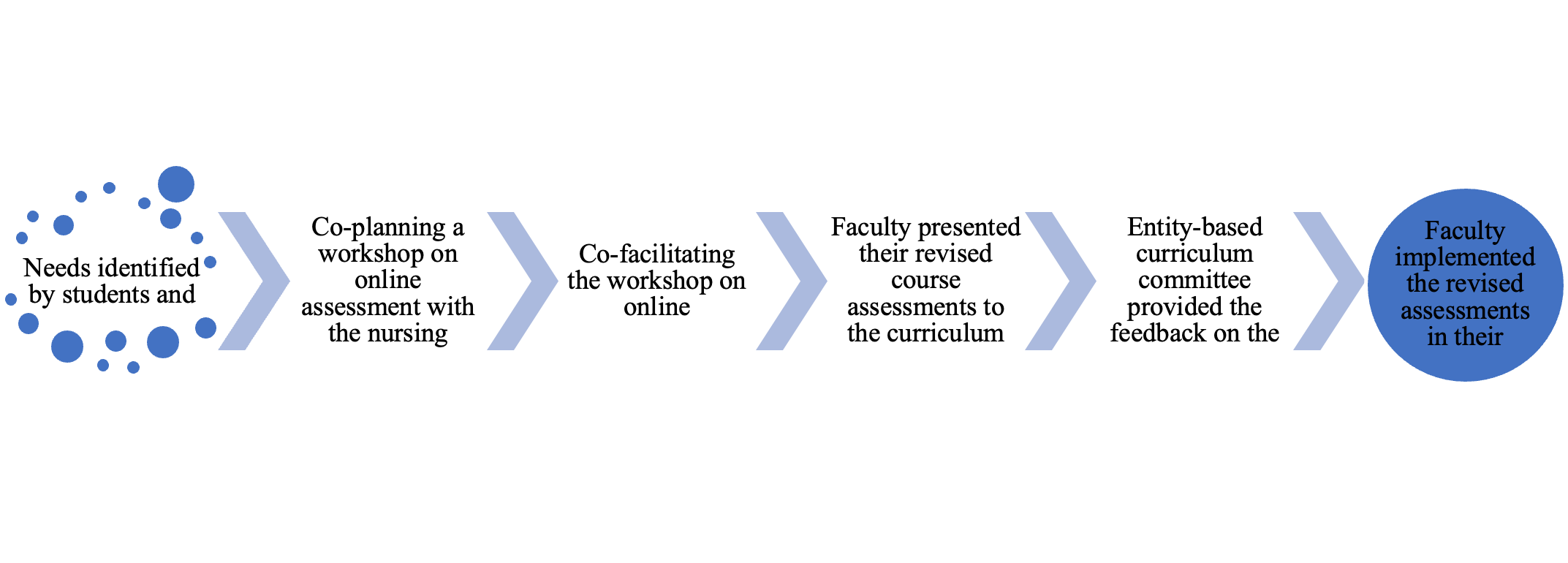

In an undergraduate health assessment course, we taught students virtually how to assess clients’ conditions, take a history, and perform client assessment. We asked students to practise these techniques on their family members with their consent. For the assessment, we asked students to request their family member to be their simulated patient, and conduct an interview and perform an assessment of any of the two systems (such as heart, lungs, eye, muscular skeleton) on them, and record it and share it with the faculty team. Students were provided guidelines for the assessment and the scoring checklist. Students were provided support by the e-learning coordinator on recording and sharing the videos. It was the first time in my life that I was sitting in my house and grading health assessment videos using a checklist. To provide feedback on their techniques, I sent them a voice message explaining their errors and areas of improvement (e.g., correct location of cardiac auscultation and the patterns of lung assessment). If it was not for the Covid lockdown, we would have done this with mannequins or standardised patients. I think this opportunity of lockdown made us think differently, redesign our assessments and conduct them successfully. It was a unique and different experience, but it was worth it. Figure 1 shows the approach taken by faculty to rethink, design, and implement a range of online assessments considering students’ varying levels of internet access.

In conjunction with this step-by-step process, the faculty experienced a holistic ‘rethinking’ of the intent of assessments.

Rethinking the purpose of the assessment

Two major functions of assessment are summative (conducted at the end of the instruction or course to determine whether students achieved the learning outcomes) and formative (conducted during the implementation of instruction (unit or course) to identify areas of improvement, provide feedback, and facilitate learning experiences) (Black et al., 2003).

Like other practice disciplines, nursing prioritises skills and practice, due to alignment with human health and safety. Assessment of practical skills (summative assessment) assures competence and signals accountability to the health profession and accreditation bodies. The focus of assessment is to ‘protect’ the ‘integrity’ of the discipline by ensuring the attainment of student competencies. Given the necessity of ‘adequate’ nursing practice, assessment often becomes a high-stakes exam (i.e., pass/fail), to monitor the achievement of competencies rather than a means to help students identify areas for potential development or to provide adequate support. The formative function of the assessment is minimal, if not lost.

To enhance the linkage of the formative and summative purposes and to serve student learning, faculty must see assessment as a mechanism to help students identify the areas of potential improvement and requiring effort to improve their practice. Rethinking the purpose of assessment as being ‘for’ learning rather than ‘of’ learning helped faculty taking part in the workshop to shift their attention ‘probability of cheating and academic malpractice in online assessment’ to designing tasks where students can demonstrate their learned skills and identify the areas where they need practice, thus, changing the purpose of assessment from judging ‘one-off’ learning of skills, to identifying areas for growth and potentiating life-long learning. As a result, faculty build trust in students and acknowledge students can take responsibility for their learning and regulate their learning when afforded adequate support and practice. A faculty member stated:

In the ‘Palliative Care’ course, in the post-RN program, we used formative assessments to assess students’ communication skills and provision of end-of-life care using virtual simulation. Previously this module was in a face-to-face format because end-of-life care is a very sensitive topic and requires students to exhibit empathetic touch and effective communication. Since many students have experienced the deaths of their loved ones, recall of such memories can make students feel uncomfortable and emotional, so it was difficult to provide emotional support to the student nurses in such situations. For example, one student burst into tears during the virtual simulation process, and we called her hostel-mate to help her settle. Despite these challenges, one of the course objectives (i.e., development of communication skills) was largely achieved, although there were instances when virtual simulation could not help in an exhibiting how student nurses create an ’emotionally safe’ environment for the patient.

The summative assessment on palliative care was carried out through a webinar on palliative practices learned during the virtual course (Kurji, 2021). Faculty developed a rubric was adapted to fit the Zoom-based webinar and shared the guidelines with the students. The webinar was conducted for the nursing community across Pakistan and was joined by other nurses from the country. In case of internet instability, the students were given alternative assessment options (i.e., written reflection or recorded seminar). Students were fearful and anxious about managing Zoom-based seminars because of potential connection instability and the novelty of virtual seminars; however, the seminar was well received.

Rethinking the design and the tools for assessment

Covid-19 provided the opportunity to reflect on the nature of skills assessed in face-to-face Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCEs) and other skill-based examinations. The possibility of conducting an online assessment of cognitive skills, such as decision-making regarding types of drugs to be administered, communication with the patient, patient counselling, history taking, interpretation of data, and evidence was realised. Multiple assessment tools were explored, such as vodcasts, podcasts, scenario-based questions and Zoom-based viva exams. One faculty member stated:

In the Adult Health Nursing course, we innovated a case-based online viva exam where students were given time to access virtual cyberpatient cases, take client history, and examine them virtually. Next, on the exam day and at the assigned time, faculty connected with the individual student and asked critical questions on the nursing process about the patient case. Students were asked to identify patient problems based on their assessments, and a formulate nursing diagnosis. Questions explored students’ understanding of the disease process, the scientific rationales, and patient management plans Where students did not have internet connections, faculty provided an option to record the video and share it via Universal Serial Bus (USB) devices sending it to the campus mailing address.

The lockdowns also taught students to take responsibility for their own learning. Post-Covid lockdown, when students joined the campus-based education, we found the students took greater responsibility for their learning by arranging and asked the faculty members to continue teaching online, instead of calling students on-campus, especially in instances of group discussion meetings and lectures.

For the SoNAM-PK faculty, the pandemic was a tipping point in their recognition of the possibilities of conducting case-based assessment and performance exams virtually for the first time. Whilst many students could access the internet and could perform the exams virtually, options for WhatsApp (a social networking application) and telephonic-viva exams were established for the students who were internet or technology compromised to assist with completing activities or transfers of their vodcasts through a learning management system.

Whilst cognitive skills were possible to gauge in virtual settings, complex clinical performance skills, such as administration of medications, technical nursing skills, and patient care management, were difficult to judge within the available staff and technological device capacities. So these were therefore postponed until the next semester. With this evolving understanding of time and resource needs, future collaborations can be established with local health centres where students are primarily located, enabling faculty to train on-site practising nurses to evaluate students’ performance skills at bedside settings if necessary.

Lessons learnt

QTL_net has consistently leveraged the ‘superpowers’ of technology and collaboration between SoNAM-PK teaching champions, teaching and learning centre (QTL_net), information and technology (IT) services, and educational experts from other schools and universities (Khamis & Salim, 2022). These ‘superpowers’ were tested and proved efficient even in times of crisis. Through the partnership with SoNAM-PK faculty, QTL_net identified needs of the faculty, implemented the workshop, and facilitated the school in creating post-workshop mechanisms in providing support and feedback to faculty to augment the design and implementation of the online assessment. Leveraging the power of collaboration, faculty and students could continue the educational experience and explore new possibilities of online instruction and assessment amidst the health crises associated with the Covid-19 pandemic.

The pandemic exposed existing issues, such as gender and the digital divide, within the SoNAM context. However, it became a catalyst for reflection and rethinking the purpose of education, more broadly, and of assessment, specifically. Faculty at SoNAM and QTL_net staff used this pandemic-induced lockdown to leverage the power of technology, rethink the remit of skills assessed in the program, and identify skills that can be taught and assessed by successfully leveraging the power of technology. For example, the use of online cases and virtual simulated patients were realised to assess nursing related skills. Besides, student-led webinars were a potential source not only to assess students’ understanding but to spread awareness in the nursing community, especially in areas such as palliative care, where there is limited national and regional expertise.

Designing an online learning experience during the Covid-19 pandemic was a challenging experience, requiring multiple levels of collaboration and engagement. We learned that faculty need to be empathetic and understand students’ situations in developing context-specific solutions. These solutions required a dedicated and joint effort of instructional designers, faculty members, educational developers, and IT staff for faculty to teach and assess online. Faculty leveraged this joint expertise in learning sciences, nursing education, and IT to design evidence-based student learning experiences.

Conclusion

While the faculty attempted to conduct fair and equitable assessments online by trusting students and providing them with the choice to select the best option for their circumstances, many assessment tasks were implemented for the first time. The validity and reliability will improve over time based on accumulated evidence and experience.

Collaboration and partnership with external health clinics and hospitals in the areas where students reside can be further developed to conduct assessments during the Covid-19 pandemic and explore the possibility of establishing post-pandemic remote assessment centres. Pivoting on these partnerships can provide students with an enriched experience closer to home, help them identify the local needs of their communities, and develop relevant and context-appropriate nursing experiences in their contexts.

References

Black, P., Harrison, C., Lee, C., Marshall, B., & William, D. (2003). Formative and summative assessment: Can they serve learning together? [Conference paper]. AERA, Chicago, 23.

https://www.academia.edu/19477022/Formative_and_Summative_Assessment_Can_They_Serve_Learning_Together

Cassum, L. A., Lakhani, A., Sachwani, S., Salim, Z., Feroz, R., & Cassum, S. (2024). Beyond the classroom walls: Stakeholder experiences with remote instruction in Post RN baccalaureate nursing program during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative inquiry. Plos one, 19(4), e0300007.

Khamis, T., & Salim, Z. (2023). Quality Teaching and Learning: A networked approach across Pakistan and East Africa. In O. Neilser (Ed), The Palgrave Handbook of Academic Professional Development Centers (pp. 331-350) Palgrave.

Kurji, Z. Aijaz, A. Aijaz, A, Jetha, Z., & Cassum, S. (2021). Telesimulation Innovation on the Teaching of SPIKES Model on Sharing Bad News, Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs, 8(6), 623–627. https://www.apjon.org/text.asp?2021/8/6/623/325645

Rizvi, N., Mubeen, K., Cassum, S., Khuwaja, H. M. A., Salim, Z., Ali, K. Q., … & Petrucka, P. (2022). Introducing ACTFAiREST2 to implement online assessments amid COVID–19: a case study from a low resource setting. BMC nursing, 21(1), 361.

Walker, D. J. (2007, May 29-31). Principles of good online assessment design [Keynote presentation]. International Online Conference on Assessment design for learner responsibility. Re-Engineering Assessment Practices in Scottish Higher Education (REAP).

https://www.reap.ac.uk/reap/reap07/Portals/2/CSL/keynotes/david%20nicol/Principles_of_good_assessment_and_feedback.pdf