16 Affective disorders

Dr Andrew Young

Learning Objectives

- Know the main symptom clusters associated with affective disorders, including bipolar disorder and major depression

- Be aware of the diagnostic criteria used

- Know the fundamentals of the monoamine theory of depression

- Understand the theoretical underpinning of current approaches to pharmacological therapy for depression, based on the monoamine theory, and appreciate the short-comings of current approaches

- Understand the theoretical basis linking depression to abnormalities in stress responses in the brain and appreciate how this theoretical framework informs novel antidepressant drug development.

Overview of affective disorders

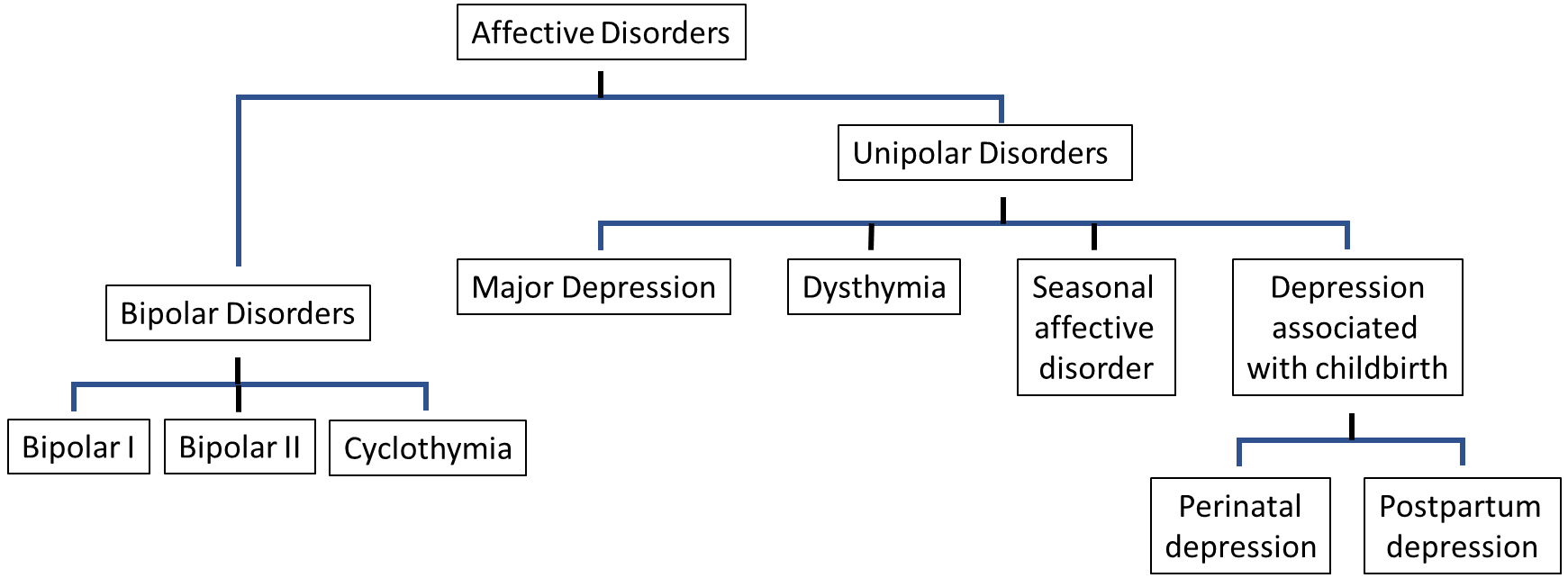

Affective disorders, or mood disorders, are a group of psychological disturbances characterised by abnormal emotional state, and generally manifest as depressive disorders. When considering depressive disorders, the two most prevalent conditions are unipolar (major) depression and bipolar disorder, characterised by alternating depression and mania, although other conditions including dysthymia, cyclothymic disorder, seasonal affective disorder and pre and post-natal depression are also important (Figure 6.4). They occur across the lifespan, although incidence in pre-adolescents is low, and their characteristics are essentially the same across all ages and across cultures.

Depression is characterised by persistent feelings of sadness, loss of interest, feelings of worthlessness and low self-esteem. Major depression and dysthymia share similar symptoms, with prolonged bouts of depressed mood: the main difference is the severity of the symptoms, with dysthymia showing less severe and less enduring symptoms. Bipolar disorder, on the other hand is characterised by similar periods of depression, but interspersed with periods of extreme euphoria, high activity and excitement and inflated self-esteem, termed mania. As with the depressive illnesses, the main difference between bipolar I, bipolar II and cyclothymia is the severity of the symptoms and the degree of interference with daily life.

Diagnosis of affective disorders uses diagnostic criteria laid down in the American Psychiatric Association International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (DSM-5) or the World Health Organisation’s International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11), which focus on the key features of the condition and give guidance to clinicians for diagnosing the conditions.

Bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder, formerly called manic depression, is characterised by cycles of extreme mood changes, from periods of a severely depressed state, resembling major depression (see below), to periods of extreme euphoria, high activity and excitement (termed mania). During a manic period people may experience inflated self-esteem and poor judgement, which may lead to them undertaking risky and often destructive behaviours; and a reduced need for sleep and a general restlessness, accompanied by physical agitation and a reduced ability to concentrate. They often deny that there is anything wrong, and become irritable, particularly when challenged about dubious decision making. It is not clear what causes mania. Genetic factors are implicated, since bipolar disorder tends to run in families, although no specific genes have yet been identified that link to it. However, genetic factors only account for around half of the vulnerability, so clearly environmental and social factors are also important.

There are three levels of severity of bipolar disorder. Bipolar I is the most severe form, and is characterised by manic episodes which last at least a week, while depressive episodes last for at least two weeks. The symptoms of both can be very severe and often require hospitalisation. Bipolar II is similar, but less severe: in particular, the manic episodes are less intense, and less disruptive (often termed hypomania) and do not last as long. People with bipolar II are normally able to manage their symptoms themselves, and rarely require hospitalisation. There is a risk of progressing to bipolar I disorder, without correct treatment, but this can be kept to around 10% with the correct management. The least severe category is cyclothymia disorder, where people experience repeated and unpredictable mood swings, but only to mild or moderate degrees.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of bipolar disorders require presence of both depressive symptoms (as below) and three or more of the listed features of mania (extreme euphoria, high activity, inflated self-esteem, poor judgement: see ‘Diagnostic criteria for bipolar I disorder’ box below). The main difference between diagnostic criteria for bipolar I, bipolar II and cyclothymia are the degree of severity and the time course of the expression of symptoms.

Diagnostic criteria (DSM-5) for bipolar I disorder

For a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder, it is necessary to meet the following criteria for a manic episode. The manic episode may have been preceded by and may be followed by hypomanic or major depressive episodes.

Manic episode

A distinct period of abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood and abnormally and persistently increased goal-directed activity or energy, lasting at least 1 week and present most of the day, nearly every day.

During the period of mood disturbance and increased energy or activity, 3 (or more) of the following symptoms (4 if the mood is only irritable) are present to a significant degree and represent a noticeable change from usual behaviour:

- Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity

- Decreased need for sleep

- More talkative than usual or pressure to keep talking

- Flight of ideas or subjective experience that thoughts are racing

- Distractibility

- Increase in goal-directed activity or psychomotor agitation

- Excessive involvement in activities that have a high potential for painful consequences

- The mood disturbance is sufficiently severe to cause marked impairment in social or occupational functioning, or to necessitate hospitalisation to prevent harm to self or others, or there are psychotic features.

- The episode is not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance (e.g., a drug of abuse, a medication, or other treatment) or to another medical condition.

Source: The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.; DSM–5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013)

Incidence of bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder is present in around 2% of the population, with bipolar I more common than bipolar II: lifetime prevalence is 1% and 0.4% respectively. Unlike major depression (see below) bipolar disorders are equally prevalent in males and females. Bipolar disorder can occur at any stage in the lifespan, although it is rare in pre-adolescents. Peak age of onset is between 15 and 25 years, although diagnosis may be considerably later, with the average age of onset of bipolar I disorder (18 years) a little earlier than for bipolar II disorder (22 years). It is a major cause of cognitive and functional impairment and suicide in young people.

Pathology of bipolar disorder

A number of brain abnormalities have been described in bipolar disorder, some of which overlap with those seen in unipolar depression (see below), but others appear to be specific to bipolar, and may represent changes responsible for the episodes of mania. Although the underlying neuronal abnormality causing mania is not well understood, changes in a number of chemical markers related to the regulation of pathways modulating neurotransmitter function and neurotrophic pathways have been described in cortex, amygdala, hippocampus and basal ganglia, suggesting compromised intracellular chemical signalling. Notably, there is evidence for dysregulation of intracellular signalling pathways which regulate the function of a number of neurotransmitters, most notable of which are dopamine, serotonin, glutamate and GABA. This in turn may lead to the dysregulation of these transmitters which has been reported in mania. The decreased brain tissue volume reported in bipolar disorder, reflecting reduced number, density and size of neurones, may link to the compromised neurotrophic pathways leading to mild neuro-inflammatory responses and neurodegeneration reported in localised brain regions in mania. Therefore, although the pathology of mania seen in bipolar disorder is not well understood, it appears most likely that it derives from abnormalities in intracellular signalling cascades, perhaps related to localised neurodegeneration through decreased neurotrophic factors.

Treatment

First line treatment for bipolar disorder is antipsychotic medication: haloperidol, olanzapine, quetiapine or risperidone. These drugs target dopamine and serotonin signalling in the brain, and are likely to be downstream of the primary abnormalities associated with mania. If antipsychotic treatment is ineffective, then the mood stabilisers, including lithium, valproate or lamotrigine may be prescribed, either alone or in combination with antipsychotic drugs. Lithium has been widely used in the treatment of mania since its introduction in 1949, but the mechanisms through which is has its mood-stabilising effects are still poorly understood. However, recent evidence has linked it to modulation of intracellular signalling pathways, particularly involving adenyl cyclase, inositol phosphate and protein kinase C: by competing with other metal ions which normally regulate these reactions (e.g, sodium, calcium, magnesium), but which may have become dysregulated, it is able to reverse instabilities in these reactions. Interestingly, other drugs, which also have mood-stabilising effects, including valproate and lamotrigine, also modulate these same intracellular signalling cascades. Therefore, the actions of lithium and other mood-stabilising drugs on these pathways provide supporting evidence for abnormalities in these intracellular signalling mechanisms in mania, perhaps opening novel routes for pharmacological therapy, but also provide plausible mechanism through which the drugs exerts their therapeutic action.

In addition to pharmacological treatment, psychotherapy has an important role to play in treatments of bipolar disorder. This may include cognitive behaviour therapy, which helps the individual to manage stress, and replace unhealthy negative beliefs with healthy positive beliefs; and well-being therapy which aims to help the individual manage stress, replace negative beliefs with positive beliefs and improve quality of life generally, rather than focusing on the symptoms. Psychotherapy is particularly important in managing cyclothymia, to minimise the risk that it will develop into bipolar I or II disorder.

Major depression

Major depression is characterised by persistent feelings of sadness, which manifests as enduring and pervasive, ‘blocking out’ all other emotions. Associated with this is a loss of interest in aspects of life (termed anhedonia) which may start as general lethargy, but in its extreme it is a complete loss of interest in all aspects of daily life, including health and well-being. In addition to these emotional symptoms there is also a spectrum of physiological and behavioural symptoms, including sleep disturbances, psychomotor retardation or agitation, catatonia, fatigue or loss of energy. There are also cognitive symptoms including poor concentration and attention, indecisiveness, worthlessness, guilt, poor self-esteem, hopelessness, suicidal thoughts and delusions with depressing themes. Dysthymia, also termed persistent depressive disorder (DSM-5) essentially relates to similar symptoms, but less severe and with a more chronic time course. An individual can suffer from both major depression and dysthymia, which is termed double depression.

Diagnosis

The diagnostic criteria for major depression according to DSM-5 require the occurrence of feelings of sadness or low mood and loss of interest in the individual’s usual activities, occurring most of the day for at least two weeks (Table 2). Importantly, the symptoms must cause the individual clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning, and must not be a result of substance abuse or another medical condition. Diagnosis of dysthymic disorder is similar to that for major depression, but less severe: symptoms in all domains are at the mild to moderate level.

Summary of DSM-5 criteria for Major Depressive Episode

Five (or more) of the following have been present during the same two-week period and represent a change from previous functioning; at least one of the symptoms is either (a) depressed mood or (b) loss of interest or pleasure:

- Depressed most of the day, nearly every day

- Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities most of the day, nearly every day

- Significant weight loss when not dieting or weight gain or decrease or increase in appetite nearly every day

- Insomnia or hypersomnia nearly every day

- Psychomotor agitation or retardation nearly every day

- Fatigue or loss of energy nearly every day

- Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt nearly every day

- Diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness, nearly every day

- Recurrent thoughts of death, recurrent suicidal ideation without a specific plan, or a suicide attempt or a specific plan for committing suicide

- The symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning

- The episode is not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance nor to another medical condition

- The occurrence of the major depressive episode is not better explained by schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, delusional disorder, or other specified and unspecified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders

- There has never been a manic episode or a hypomanic episode.

Source: The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.; DSM–5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013)

Incidence

The overall prevalence of depression worldwide is estimated at around 5% of the population. Although there are some regional variations, prevalence rates world-wide are fairly similar with women around twice as likely (5 to 6%) as men (2 to 4%). As with bipolar disorder, incidence in pre-adolescents is very low, but the condition begins to emerge in adolescence, peaks in late middle age and then declines in old age. World-wide, depression is the leading cause loss of functionality at the population level, including absence from work and treatment costs, and major depression is the most prevalent mental disorder associated with the risk of suicide.

Causes of depression

Like many mental illnesses, the underlying cause is not yet known. It is likely that genetic, environmental and social factors contribute, and the exact origin may be different in different people. The main risk factors for an individual developing depression are a family history of depression, particularly if they experience severe or recurrent episodes, a history of childhood trauma, and major stressful life changes. In addition, some physical illnesses and medications can bring on a depressive episode.

Evidence suggests that offspring of people who suffer major depression are 2 to 3 times more likely to suffer from major depression themselves compared to the rate in the populations as a whole. This figure rises to 4 or 5 times greater risk if we consider only offspring of parents with recurrent depression or depression which developed early in life. Studies on identical twins suggest that major depression is around 50% hereditable, although this may be higher in the case of severe depression. Although there is clearly a genetic link, there is no one gene which is responsible for this vulnerability. Rather a vulnerability for depression is promoted by combinations of genetic changes. In adoption studies, a higher risk of an adopted child developing depression has been found if an adoptive (unrelated) parent has depression than if they are unaffected. This gives a clear indication that, as well as genetic influences, parents also clearly have a social influence.

Stress seems to be the most important environmental factor involved in the incidence of depression. The stress-diathesis model puts forward the notion that it is the interaction between stress and the individual’s genetic background which determine the expression of depression. Studies on childhood trauma show that children who have experienced emotional abuse, neglect and sexual abuse have an increased likelihood of developing depression in the future of around three-fold, and around 80% of depressive episodes in adults are preceded by major stressful life events. Therefore it is likely that stressful life events, be they in the distant past or more recent, are both a vulnerability factor and a precipitatory factor in the origin of depression.

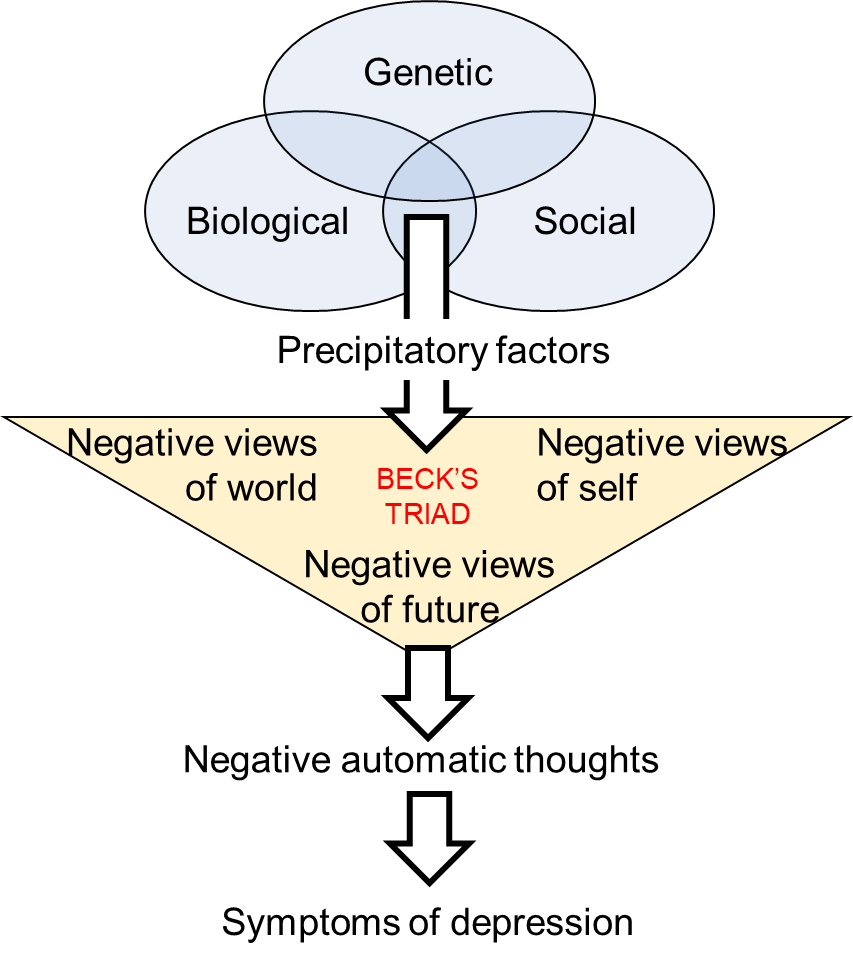

Beck’s cognitive triad provides a mechanism through which stressful life events may impact on altered cognition leading to a tendency to interpret every-day events negatively leading to the development of depression. Essentially he proposed that the combination of early life experiences and acute stress led to negative views of oneself, the world and the future (the cognitive triad), which in turn created negative schema with a cognitive bias towards negative aspects of a situation, an overemphasis on negative inferences and an overgeneralisation of negative connotations to all aspects of a situation. While these factors may in themselves be sufficient to invoke a depressive episode, it becomes more likely in those with a genetic predisposition (Figure 6.5).

Vulnerability is brought about by a combination of a genetic predisposition, biological factors (e.g. brain structure, hormones) and social factors (e.g. upbringing, childhood trauma). Precipitatory factors, such as stressful life events, trigger negative views on one’s self, the world and the future leading to negative automatic thoughts, including negative attribution, and the symptoms of depression.

Brain structural abnormalities in depression

In the search for a biological origin for depression no consistent abnormalities in brain structure or connectivity have been identified linked to depression. There have been reports of decreased tissue volumes in prefrontal, anterior cingulate cortices and hippocampal regions associated with major depression, but results across studies are inconsistent, although individuals with reduced hippocampal volume seem to be more prone to relapse. Neuroimaging studies have found a number of functional abnormalities in localised brain regions associated with depression, with prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortices emerging as the most likely areas of dysfunction, but again there is a lack of consistency between studies. A decrease in metabolism has been reported in dorsal prefrontal cortex, which is reversed after antidepressant treatment. Decreased metabolism has also been reported in the ventral portion of the anterior cingulate cortex, a region that has extensive connection with brain regions involved in mood regulation, including amygdala, orbitofrontal cortex and medial prefrontal cortex. On the other hand, insular volume and insular activation in response to negative stimuli has been reported to be increased in major depression, suggesting a heightened sensitivity to adverse stimuli and situations. It has been suggested that depression is not caused by an abnormality in a single brain region, but rather imbalances of connectivity distributed across a number of brain regions. Connectivity studies have shown that the decrease in metabolism in regions of the frontal cortex correlates with increased metabolic function in striatal areas, suggesting a dysregulation of corticostriatal networks in depression.

The monoamine theory of depression

The drug reserpine, extracted from the Indian snake root plant, was historically used as a tranquilliser and for treating hypertension. It was found to cause severe, often suicidal tendencies in patients treated with it. In the 1960s, it was found that the pharmacological action of reserpine is to deplete releasable monoamine neurotransmitters (dopamine, noradrenaline, serotonin) in the terminals, by preventing their storage in vesicles. This therefore supports the view that depression may be accompanied by a reduction in monoamine neurotransmitters, a view that was brought together by Joseph Schildkraut in 1965 in the monoamine theory of depression, in which he concluded that depression is caused by reduced monoamine neurotransmitter function. Subsequently, the primary importance of serotonin and noradrenaline were realised, with dopamine playing a lesser role. This is consistent with the observation that many of the drugs used to treat depression are more effective in influencing serotonin and noradrenaline systems than dopamine systems.

Serotonin is involved in many functions which are disrupted in depression, including pain sensitivity, emotionality and responses to negative consequences. Some studies have shown that the serotonin metabolite, 5HIAA, is reduced in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of depressed patients, although the data are inconsistent. Low 5-HIAA seems to be particularly associated with aggressive hostile and impulsive behaviour and has been reported in violent suicide attempts. Decreased serotonin is found in post mortem brains of some depressed patients, but again the data are inconsistent. Thus, overall depression does seem to be associated with decreases in brain serotonin function.

There is little evidence of decreased noradrenaline or noradrenaline function in post mortem brains of depressed people. Although some studies found changes in the noradrenaline metabolite (MHPG) in CSF or blood of depressed patients, no consistent decrease has been found in depressed patients, as would be predicted if decreased noradrenaline levels were causing depressive symptoms. However, increased MHPG has been observed after successful treatment with antidepressant, which would be consistent with the antidepressants increasing noradrenaline function. Therefore, though these findings suggest some involvement of noradrenaline in depression, the precise relationship is not clear.

Treatment

Prior to the 1950s, there were no suitable drug treatments available to treat the symptoms of major depression. Earlier drug treatments were non-specific and simply aimed at suppressing troublesome symptoms, often by extreme sedation. Relief of symptoms was poor and many patients developed dependence and/or toxic reactions. Shock therapy, first introduced for the treatment of schizophrenia in the 1930s, involves inducing seizures, which were seen to be beneficial in treating mental disorders. Early shock treatment used insulin shock and chemical shock (Cardiazol) but an alternative to these, electroconvulsive shock (ECT), was introduced in the 1940s: this involved passing an electrical current through the brain, inducing seizures. It was seen as a safer way of inducing seizures than either insulin or Cardiazol, and became widely used in the treatment of mental disorders, including depression. The induction of severe seizures, although therapeutically beneficial, often caused fractures, broken teeth and torn muscles and ligaments from the violent convulsions, and in many cases left residual long-term amnesia and personality changes. Although ECT is still used in extreme cases, where patients do not respond to drug treatment, it now performed in a controlled environment using much lower currents, and is carried out using muscle relaxants and under general anaesthetic to prevent injury and distress during the procedure. Although the precise mechanism of ECT is not fully understood, it appears to cause changes in brain chemistry which rapidly alleviate symptoms of a number of mental conditions including depression. ECT is one of the most effective treatments for severe depression, particularly in patients who do not respond to drug treatment.

Monoamine therapy

In the early 1950s, a drug called iproniazid was being used as an antibiotic in the treatment of tuberculosis, and clinicians reported that it also seemed to elevate the mood of the patients. It was therefore tested on depressed patients and found to alleviate the symptoms of depression. Empirical studies ensued and in 1956 the first formal report of an antidepressant effect of iproniazid was published by Kline in 1956, and it was subsequently marketed as an antidepressant. Pharmacologically, iproniazid is a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MOAI). It blocks the action of the enzyme, monoamine oxidase, which breaks down the monoamine neurotransmitters serotonin, noradrenaline and dopamine, thus increasing their concentrations in the synaptic cleft. The therapeutic benefits seen with iproniazid suggest that these monoaminergic transmitters may be depleted in depression. In particular, iproniazid blocks MAO-A, which breaks down serotonin and noradrenaline preferentially, whereas dopamine is broken down by MOA-B. These effects of iproniazid form part of the evidence that changes in serotonin and noradrenaline are more important in depression than dopamine changes.

MAOIs are associated with a number of side effects mediated in the brain, including insomnia, confusion, drowsiness and nausea. However, the most problematic, called tyramine-induced hypertension crisis, derives from the fact that as well as blocking the breakdown of monoamine neurotransmitters, MAOIs also block the breakdown of the amino acid, tyramine, in the liver. This leads to an increase of tyramine in the blood causing dangerous increases in blood pressure and intracranial bleeding, which can be fatal. Therefore care with diet is necessary, since many foods contain high levels of tyramine. One such food is cheese, hence it is commonly called the ‘cheese effect’, but also include wine and chocolate.

Newer reversible inhibitors of MAOIs (RIMA: e.g. moclobemide) reduce this danger. Unlike standard MOAIs, which once bound to the enzyme remain bound, binding of the RIMAs is reversible. Therefore, when tyramine concentrations increase it competes with the drug for binding at the enzyme. In this way tyramine levels never reach the dangerous levels required to trigger tyramine-induced hypertension crisis.

Another class of drugs which largely superseded MAOIs are the tricyclic antidepressants, so called because of their chemical structure containing three benzene rings. The first of these was imipramine, which was approved for use in 1959: structurally it is similar to the antipsychotic drug, chlorpromazine, and actually derived from drug development to try to isolate a drug with similar antipsychotic properties as chlorpromazine, but without the motor side effects. Imipramine showed very little antipsychotic effect, but did have antidepressant properties. Since then a number of other tricyclic antidepressants have been developed, including amitriptyline, clomipramine, desipramine and nortriptyline. Pharmacologically, they inhibit the reuptake of serotonin and noradrenaline back into the terminal after release. As with MAOIs, this prolongs the time the transmitter molecules are in the synaptic cleft and therefore increases their trans-synaptic signalling. Interestingly, the tricyclics with the best antidepressant profile are those which primarily block serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake: those which block dopamine reuptake are less effective, supporting the view that dopamine is less involved in the origin of depression than serotonin or noradrenaline. The main problem with the tricyclic antidepressants is that they are not very specific: therefore as well as blocking monoamine reuptake they are also antagonists at acetylcholine, noradrenaline and histamine receptors. Therefore, not surprisingly, as well as treating depressive symptoms they also have wide ranging side-effects, most notably hypotension, cardiac arrhythmia/arrest, sedation and memory disturbances, some of which can be fatal, particularly in overdose. Although they are effective and relatively cheap, the side effects limit compliance and they are generally no longer used as a first line treatment.

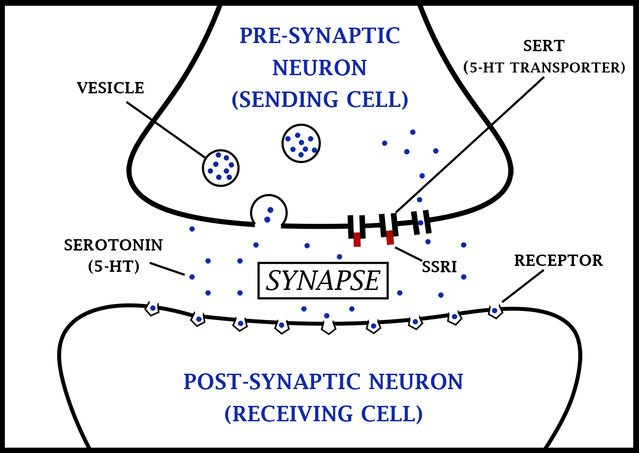

The efficacy of tricyclic antidepressants paved the way for the development of more specific drugs, which have the required therapeutic action, but without the problematic side effects. These are serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (NRIs), and serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRI) which, as their names indicate, block only reuptake of serotonin, noradrenaline or serotonin and noradrenaline respectively, without having the non-specific effects on other neurotransmitter systems which cause the array of side effects seen with tricyclics. These drugs show much better clinical efficacy, with fewer side-effects (although they do still produce some side effects), thus improving compliance.

SSRIs are powerful inhibitors of serotonin reuptake, with minimal effects on noradrenaline reuptake, or on other neurotransmitter systems. Examples include fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline and citalopram. As such they induce fewer side effects, although those that they do induce are mediated through serotonin systems outside the primary therapeutic targets in the brain, and are therefore hard to dissociate from the required therapeutic action. These side effects include acute anxiety and panic attacks, akathisia (constant restlessness and inability to remain still), sleep disturbances and nausea.

SNRIs inhibit the reuptake of both serotonin and noradrenaline, and as such show a similar reuptake blocking action to the tricyclic antidepressants, but without receptor mediated side-effects. Examples include duloxetine and venlafaxine. Side effects of SNRIs include nausea, insomnia, and loss of appetite. NRIs, for example atomoxetine and reboxetine, block only noradrenaline reuptake. Although they are generally less effective as antidepressants, they can be a preferable therapeutic route for severe depression and where depression is accompanied by significant anxiety.

SSRIs or SNRIs are currently the first line of treatment for major depression. Although they are not fully effective in controlling the symptoms, around 50% of patients show good control of symptoms, with a further 25% showing some improvement but still exhibiting debilitating symptoms. Even in those patients where symptoms are well controlled, there is a 4 to 6 week delay before the antidepressant effect emerges. This implies that a more complex action than simply blocking of reuptake is involved, as this direct pharmacological effect will occur within 1 to 2 hours of the drug administration. The other major limitation of SSRI and SNRI treatment is the side effects associated with treatment. Although these are generally not severe or life threatening, they are nevertheless unpleasant and cause some disruption to daily life, leading many patients to discontinue drug treatment after recovery from a depressive episode, with the high risk of relapse. This therefore provides a challenge for future drug design, to develop drugs with a faster antidepressant action, which are effective in all patients and with fewer side effects.

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation

The recent advance in transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) technology has enabled targeted brain stimulation to be employed. In the field of depression, there has been some success in TMS treatments particularly stimulating areas of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. These are the same areas which have been shown to have reduced metabolism in depressed patients. Imaging studies have highlighted some functional abnormalities in brain circuits in depressed patients, and as our understanding of these aspects improves, there is the potential for this type of treatment to become more effective in a wider group of patients.

Novel approaches to antidepressant drugs

All current pharmacological approaches to treating depression derive from the monoamine theory of depression and aim to increase serotonergic and/or noradrenergic transmission. Novel drugs licensed as antidepressants over the last three decades have essentially relied on very similar pharmacology, the main improvements being in specificity, leading to reduced side-effects, and potency. While clearly these monoamines are involved, and any alternative theory as to the origin of depression must be able to account for the at least moderate efficacy of these drugs are alleviating symptoms, the anomalies highlighted above (onset delay, efficacy) suggest that they may not be targeting the core deficit. However, what holds us back in developing novel therapeutic strategies which do target the core deficit, is that the core deficit has not yet been conclusively identified.

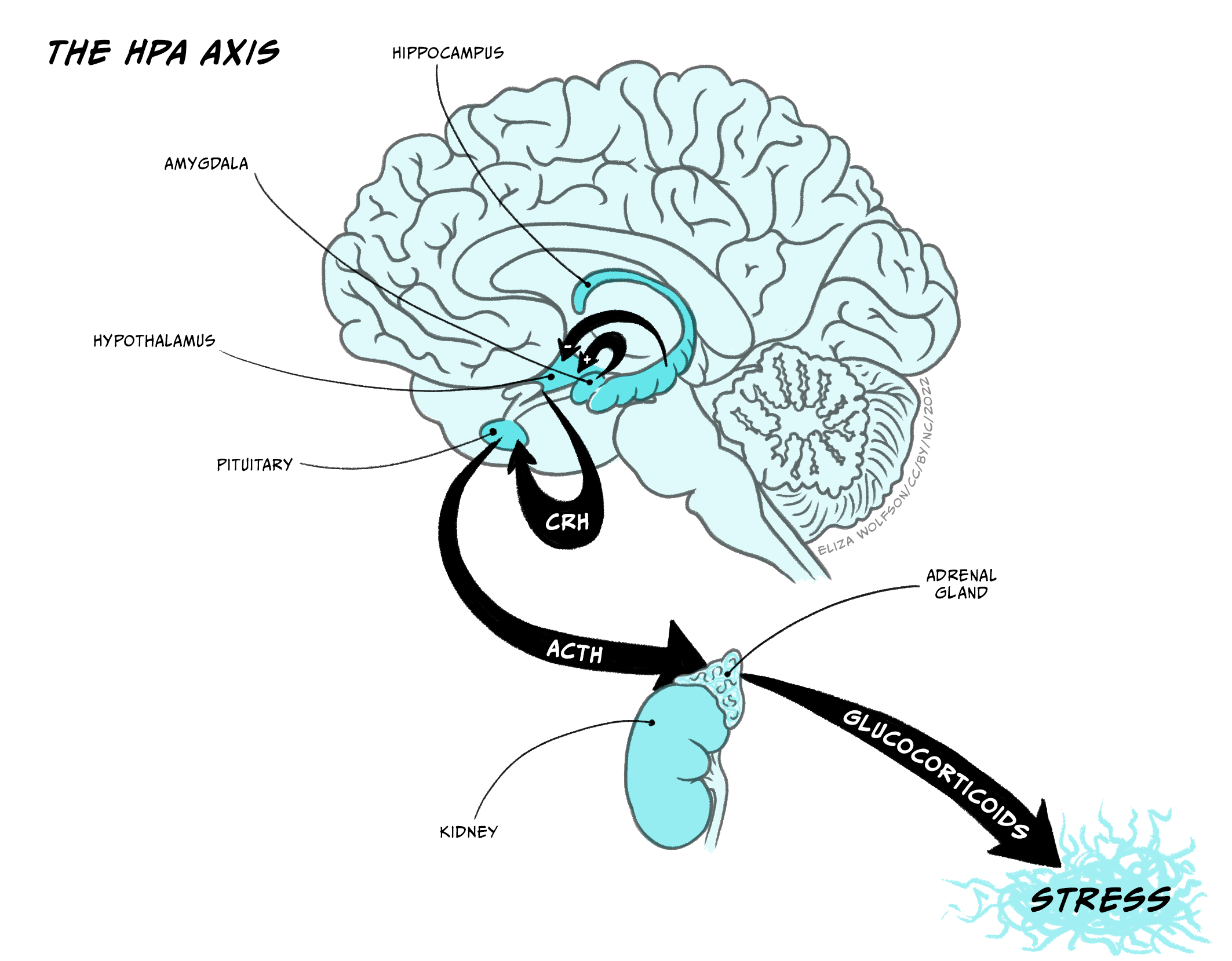

To address this issue, two key lines of evidence have been important. First, the prominence of stress as a predisposing and precipitating factor in psychological models of depression, and second, that the common process in many animal models used to study depression and antidepressants involves applying stressors to the animals (e.g. forced swim test, learned helplessness, chronic mild stress, maternal separation). These observations suggest that the body’s stress response system may be involved and that function may be compromised in depression. These stress responses are controlled in the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal cortex system (HPA-axis).

A key element of this response is the release of glucocorticoids from the adrenal cortex, a secretory organ located on the dorsal the kidneys. In humans, the main glucocorticoid is cortisol, and this is responsible for many of the reactions to stress in the body – blood pressure, heart rate, reduced gut motility, arousal, etc. Under normal conditions, high cortisol levels in the blood also act as a negative feedback mechanism in the brain to switch off the HPA-axis, by reducing activity in the corticotrophin releasing hormone (CRH) producing cells in the hypothalamus (note that CRH was previously called corticotrophin releasing factor, CRF, before its hormone characteristics were identified). Thus the stress response is self-limiting and returns to normal levels when the stressor is removed.

The Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal cortex system (HPA-axis)

The hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA-axis) is crucial in controlling the body’s response to stressors and aversive situations. Neurosecretory cells project from the hypothalamus to the pineal stalk, where they release corticotrophin releasing hormone into the pituitary postal blood capillaries. Increased CRH activates secretory cells in the posterior lobe of the pituitary (median eminence) to release adrenocorticotrophin (ACTH) into the blood system, which triggers the body’s response to the stressor – essentially the ‘fight or flight’ response. Two key inputs regulate the activity of the CRH producing cells in the hypothalamus, and through that regulate the activity in the HPA-axis. These inputs arise from hippocampus, which inhibits CRH cells, and the amygdala, which activates CRH cells. It is well documented that the amygdala is important in responses to aversive stimulation and it is likely that it is a key structure in activating HPA-axis responses to a stressor.

Several lines of evidence suggest that HPA-axis function is abnormal in depression. Many depressed patients have been found to have elevated levels of ACTH and cortisol, enlarged pituitary and adrenal glands, raised levels of CRH in cerebrospinal fluid and abnormal circadian rhythm of cortisol, all indicative of dysregulation of the HPA-axis in depression. Importantly, although the mechanism is unclear, treatment with current antidepressant drugs reduces CRH levels in depressed patients, indicating effective treatment of depression normalises, at least to some extent, the HPA dysfunction. Furthermore, Cushing’s disease, which involves excessive secretion of glucocorticoids, is commonly followed by depression, and corticosteroids used in treatment of arthritis often cause depression. Therefore there is a substantial body of clinical evidence suggesting that hyperfunction of HPA may be linked to depression.

There is also support for this view from animal studies. CRH administration in rodents causes an increase in cortisol and also increases behaviours resembling symptoms of depression (e.g. insomnia, loss of appetite), effects which are reversed by antidepressant drugs, again providing a link between current treatment and HPA-axis function. Also in rodents, maternal separation, modelling childhood trauma, causes an elevation of stress-induced CRH, ACTH and cortisol release in adulthood, and increased CRH gene expression, effects which again are reversed by antipsychotic drugs. The effects of antidepressants on augmented gene expression are of particular interest and may account for the delay in therapeutic effectiveness of these drugs, since changes in gene expression are likely to take weeks, rather than hours, to manifest.

Novel treatments strategies derived from HPA research

CRH-related therapy

In animal studies, CRH antagonists have shown an antidepressant-like profile: the CRH antagonist LWH234 decreases time spent immobile in the forced swim test. In clinical trials the CRH antagonist, R121919, shows early promise, providing a significant improvement in depression, with minimal side effects: notably, the depression worsens again after the end of drug treatment.

Neurokinin-related therapy

Animal models have shown antidepressant-like effects of NK-1 receptor antagonists and clinical trials have shown that the NK-1 antagonist, MK869, reduces depressive symptoms in patients with major depression, to a similar extent to SSRIs. Notably, however, the time course is also similar to SSRIs, so these drugs, although potentially beneficial in the future, may share the same delayed response as current medicines.

The CRH-secreting cells of the hypothalamus are under direct inhibitory control of the hippocampus. Circulating cortisol activates the hippocampus, thus increasing inhibition of the hypothalamus, providing a plausible mechanism for the self-regulating negative feedback curtailing HPA activation. Damage to the hippocampus would lead to a prolongation of HPA activation, with an increase in CRH, ACTH and cortisol. Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies have shown decreased hippocampal volume in severely depressed patients, providing evidence that such damage may have occurred. In addition, cortisol has a regulatory influence, both positive and negative, on many genes expressed in the brain, which can account for behavioural changes, including depressed mood, after continued overexposure.

Animal studies have shown that high levels of circulating cortisol have neurotoxic effects on hippocampal neurons. These include decreased dendritic branching, loss of dendritic spines (the location of synapses) and reduced hippocampal neurogenesis. This effect may be mediated through reduced levels of neurotrophic factors, in particular brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which are essential for maintaining healthy neurons: reduced BDNF compromises neuronal function, which can lead to severe functional deterioration, or even death, of the neurons. Low BDNF may be responsible for the reduction in dendrites seen with prolonged high levels of circulating cortisol. BDNF levels are decreased in the brains of people committing suicide, and chronic stress reduces hippocampal BDNF in rats and suggests promoting BDNF activity as a possible therapeutic target. BDNF is involved in a number of intracellular second messenger cascades where therapeutic drugs could act. Monoamine antidepressant drugs may protect vulnerable cells by preventing the decrease in BDNF, and importantly this may be dependent on chronic treatment, consistent with the delay in onset of therapeutic effect, although the mechanism is unclear. For example, chronic, but not acute, antidepressant treatment increases BDNF in both experimental animals and humans, and prevents stress-induced reductions in BDNF, probably through up-regulation of intracellular second messenger pathways responsible for BDNF production.

Antidepressant effects of ketamine

Ketamine, and particularly its active enantiomer, S-ketamine (esketamine) is well known as an anaesthetic, but recently has received attention in management of a number of clinical conditions, including depression, where it has been found to provide a rapid onset (within four hours) antidepressant effect in treatment-resistant depression. Although it is now licenced for use in treatment-resistant depression in the United States, uncertainties about functional outcomes, side-effects and cost effectiveness have delayed its adoption as a main-line treatment elsewhere.

The mechanism through which ketamine exerts its antidepressant action is unclear. The main documented pharmacological action of ketamine is as a non-competitive antagonist at NMDA-type glutamate receptors. However, it also has pharmacological effects at other neurotransmitter systems, including monoamine, opioid and cholinergic mechanisms, all of which may contribute to its antidepressant effect. However, ketamine also exerts a powerful regulation of intracellular signalling cascades that increase neuronal and glial trophic factors (BDNF, GDNF) and inhibit microglia associated with inflammation. These factors, in turn, lead to a decrease in neurodegeneration and an increase in neuronal proliferation and synaptogenesis. This potential mechanism of action of ketamine is particularly pertinent in view of the evidence of hippocampal degeneration and lowered BDNF in depression, and indeed, chronic ketamine treatment reverses the reduced BDNF seen in hippocampus in depression. These observations have given renewed impetus to the search for mechanisms of intracellular regulation which may be responsible for depression, and which could be novel targets for antidepressant action.

It is well documented that the amygdala is important in processing aversive and emotional stimuli. Amongst many other outputs, mediating various responses to such stimuli, the amygdala exerts an excitatory influence on CRH releasing cells in the hypothalamus. It is the balance between the excitatory input from the amygdala, present during the stressor, and the inhibitory input from the hippocampus, including from the negative feedback mechanisms, which controls the activity in the HPA-axis. Thus when the stressor is still present, the amygdala retains its excitatory drive, overcoming the inhibitory influence of the hippocampus, but when the stressor recedes the excitatory drive diminishes and the inhibitory influence from the hippocampus predominates and reduces activity HPA activity. However, if hippocampal function is compromised, the negative feedback will be ineffective, and the HPA-axis will remain active, maintaining a high concentration of circulating cortisol, potentially causing further damage to the hippocampus, creating a self-perpetuating cycle of damage. Similarly, during chronic stress, the amygdala remains active, driving the HPA-system and maintaining a potentially toxic level of cortisol in the circulation for an extended period, leading to compromise of hippocampal function. Finally, during neurodevelopment, hippocampal cells are particularly susceptible to high cortisol levels, causing potentially irreversible changes, explaining why childhood trauma may be particularly damaging.

This opens another route for potential novel therapeutic strategies, by reducing the excitatory drive from the amygdala. Neurokinin peptide neurotransmitters, including substance P, are involved in signalling about aversive stimuli, particularly in the amygdala. Some studies have shown increases in substance P in the CSF of depressed patients, suggesting abnormalities in substance P signalling, which could potentially be normalised with neurokinin (NK) receptor antagonists.

Other depressive illnesses

Although bipolar disorder and major depression are the two main types of affective illness, there are others which should not be overlooked. Seasonal affective disorder (SAD: termed Major Depressive Disorder with Seasonal Pattern in DSM-5) is a type of depression, with similar features to major depression, which is brought about by seasonal change. It affects around 2% of the population, occurring most often in young adults, and women are more affected than men. It is believed that decreased sunlight during winter months and increased sunlight in summer months affects the natural diurnal rhythms that control hormones, sleep and moods, and it is particularly prevalent in people living in extreme northerly and southerly regions of the earth, where the daylight differences between summer and winter are most extreme. Notably the majority of SAD is associated with decreased sunlight in the winter months, with only around 10% of cases associated with increased sunlight in the summer months. For winter SAD, light therapy is reasonably effective, where people are exposed to light of certain wavelengths from a specialised light box for around 30 minutes each day. Alternatively standard antidepressants and cognitive behavioural therapy are also effective.

Depression associated with pregnancy and childbirth are relatively common. Around 15% of women experience symptoms of depression during pregnancy, which, although often mild, can be severe in some cases. Similarly, after the baby is born, 60 to 80% of mothers experience mild depression, often termed ‘baby blues’, which is normally transient, with each bout lasting no more than an hour. Normally it does not occur beyond 2 to 3 weeks after birth, and does not generally require treatment more than providing practical and emotional support for the mother. More serious, though, is postpartum depression, occurring in around 10% of new mothers. Where symptoms are more severe, bouts last for longer and it continues for months or even years after birth. The cause of these depressive conditions is thought to relate to the rapid and extreme hormonal changes that occur during pregnancy and childbirth, although, like other forms of depression, social stress and trauma may trigger or exacerbate the depression. Interestingly, postnatal depression has also been found in 5 to 10% of new fathers, indicating that there cannot be an entirely hormonal basis: the stress of the changed lifestyle may also be an important trigger. Psychological therapy, including cognitive behaviour therapy and life-style advice (exercise, diet) has been found to be effective in most cases, although antidepressants are appropriate for more severe symptoms and where the symptoms do not respond to psychological treatments. Importantly, if left untreated, postpartum depression can develop into persistent major depression.

Summary

The two main affective disorders are bipolar disorder, characterised by fluctuations between severe depression and mania, and major depression characterised by severe depression alone. There are essentially three levels of bipolar disorder, distinguished by the severity of the symptoms: the most severe is bipolar I, followed by bipolar II, then cyclothymia. Similarly, dysthymia is distinguished from major depression by the less severe symptoms. The monoamine theory of depression places a major emphasis on decreased functionality of serotonin and noradrenaline in the origin of depression, and current antidepressant treatments derive very much from that view. First line treatment normally uses SSRIs or SNRIs which block the reuptake of serotonin and serotonin and noradrenaline respectively, although other classes of antidepressant drugs, tricyclic antidepressants and MAOIs, also aim to increase function of these neurotransmitters. However, none of these drugs are effective in all patients, they are all associated with side effects, some more severe than others, and there is always a delay of around 4 to 6 weeks before they begin to show antidepressant effects. Therefore an alternative therapeutic approach has been sought.

A common theme in psychological and animal models of depression is the role of stress, leading to attention being paid to the HPA-axis, the main stress control system, in relation to depression. Studies in both animal models and in depressed patients have indicated that the HPA-axis may be compromised in depression and dysregulation of the inhibitory and excitatory inputs from hippocampus and amygdala (respectively) have been implicated. In particular decreased function in hippocampus leads to reduced inhibition of the HPA-axis, and so an enhanced, or extended, stress response, and this may provide a target for future drug treatments. Importantly, also, monoamine antidepressant drugs have been shown to modulate HPA-function, particularly when given chronically, providing a plausible route for their therapeutic action, and an explanation for the delay in onset of their antidepressant action.

Key Takeaways

- The two main affective disorders are:

- Bipolar disorder, characterised by fluctuations between severely depressed mood and extreme euphoria, high activity and excitement (mania)

- Major depression (unipolar depression), characterised by a severely depressed state alone

- Mechanisms underlying bipolar disorder, and its treatment with mood-stabilising drugs are poorly understood, but are likely to involve regulation of intracellular signalling pathways controlling neuronal activity and neurotransmitter function

- The monoamine theory of depression posits that major depression is caused by an underactivityof monoamine neurotransmitters, particularly serotonin and noradrenaline

- Current treatments for major depression are based on the monoamine theory, and aim to increase the function of serotonin and noradrenaline. These treatments include monoamine oxidase inhibitors, which prevent the enzymatic breakdown of the transmitters, tricyclic antidepressants, which block the reuptake of both serotonin and noradrenaline; and specific reuptake inhibitors for serotonin (SSRIs) or both serotonin and noradrenaline (SNRIs)

- These drugs are not effective in all patients, they are relatively slow in onset, and they are accompanied by problematic side effects, meaning that for many people there is inadequate control of symptoms

- Compromised stress responses, mediated through the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal cortex (HPA) axis has been proposed as an underlying cause of depression

- Treatments targeting stages in the HPA axis signalling are showing promise as novel antidepressant drugs.

References and further reading

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th edn. American Psychiatric Publishing.

Bissette, G., Klimek, V., Pan, J., Stockmeier, C., & Ordway, G. (2003). Elevated concentrations of CRF in the locus coeruleus of depressed subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 28(7), 1328–1335. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300191

Deussing, J. M. (2006). Animal models of depression. Drug discovery today: disease models, 3(4), 375-383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ddmod.2006.11.003

Elhwuegi, A. S. (2004). Central monoamines and their role in major depression. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 28(3), 435-451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2003.11.018

Gainetdinov, R. R., & Caron, M. G. (2003). Monoamine transporters: from genes to behavior. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology, 43, 261-284. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.43.050802.112309

Holsboer, F. (2000). The corticosteroid receptor hypothesis of depression. Neuropsychopharmacology, 23(5), 477-501. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00159-7

Kato, T. (2019). Current understanding of bipolar disorder: Toward integration of biological basis and treatment strategies. Psychiatry and clinical neurosciences, 73(9), 526-540. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.12852

Kramer, M. S., Cutler, N., Feighner, J., Shrivastava, R., Carman, J., Sramek, J. J., Scott, A.R., Guanghan, L., Snavely, D., Wyatt-Knowles, E., Hale, J.J., Mills, S.G., MacCoss, M., Swain, C.J., Harrison, T., Hill, R.G., Hefti, F., Scolnick, E.M., Cascieri, M.A., …Rupniak, N. M. (1998). Distinct mechanism for antidepressant activity by blockade of central substance P receptors. Science, 281(5383), 1640-1645. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.281.5383.1640

Matrisciano, F., Bonaccorso, S., Ricciardi, A., Scaccianoce, S., Panaccione, I., Wang, L., Ruberto, A., Tatarelli, R., Nicoletti, F., Girardi, P., & Shelton, R. C. (2009). Changes in BDNF serum levels in patients with major depression disorder (MDD) after 6 months treatment with sertraline, escitalopram, or venlafaxine. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 43(3), 247-254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.03.014

McIntyre, R. S., Rosenblat, J. D., Nemeroff, C. B., Sanacora, G., Murrough, J. W., Berk, M., Brietzke, E., Dodd, S., Gorwood, P., Ho, R., Iosifescu, D.V., Jaramillo, C.L., Kasper, S., Kratiuk, K., Lee, J.G., Lee, Y., Lui, L.M.W., Mansur, R.B., Papakostas, G., …Stahl, S. (2021). Synthesizing the evidence for ketamine and esketamine in treatment-resistant depression: an international expert opinion on the available evidence and implementation. American Journal of Psychiatry, 178(5), 383-399. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20081251

Nemeroff, C. B. (1998). The neurobiology of depression. Scientific American, 278(6), 42-49.

Nestler, E. J., Gould, E., & Manji, H. (2002). Preclinical models: status of basic research in depression. Biological Psychiatry, 52(6), 503-528. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01405-1

Nestler, E. J., & Hyman, S. E. (2010). Animal models of neuropsychiatric disorders. Nature Neuroscience, 13(10), 1161-1169. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.2647

Ng, J., Rosenblat, J. D., Lui, L. M., Teopiz, K. M., Lee, Y., Lipsitz, O., Mansur, R.B., Rodrigues, N.B., Nasri, F., Gill, H., Cha, D.S., Subramaniapillai, M., Ho, R.C., Cao, B., & McIntyre, R. S. (2021). Efficacy of ketamine and esketamine on functional outcomes in treatment-resistant depression: a systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 293, 285-294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.06.032

Pizzagalli, D. A., & Roberts, A. C. (2022). Prefrontal cortex and depression. Neuropsychopharmacology, 47(1), 225–246. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-021-01101-7

Rupniak, N. M. (2002). New insights into the antidepressant actions of substance P (NK1 receptor) antagonists. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology, 80(5), 489-494. https://doi.org/10.1139/y02-048

Scheepens, D. S., van Waarde, J. A., Lok, A., de Vries, G., Denys, D., & van Wingen, G. A. (2020). The Link Between Structural and Functional Brain Abnormalities in Depression: A Systematic Review of Multimodal Neuroimaging Studies. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 485. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00485

Schildkraut, J. J. (1965). The catecholamine hypothesis of affective disorders: a review of supporting evidence. American journal of Psychiatry, 122(5), 509-522. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.122.5.509

Takamiya, A., Kishimoto, T., & Mimura, M. (2021). What Can We Tell About the Effect of Electroconvulsive Therapy on the Human Hippocampus?. Clinical EEG and Neuroscience. https://doi.org/10.1177/15500594211044066

Waters, R. P., Rivalan, M., Bangasser, D. A., Deussing, J. M., Ising, M., Wood, S. K., Holsboer, F., & Summers, C. H. (2015). Evidence for the role of corticotropin-releasing factor in major depressive disorder. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 58, 63-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.07.011

Zhang, F. F., Peng, W., Sweeney, J. A., Jia, Z. Y., & Gong, Q. Y. (2018). Brain structure alterations in depression: Psychoradiological evidence. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics, 24(11), 994-1003. https://doi.org/10.1111%2Fcns.12835

Zobel, A. W., Nickel, T., Künzel, H. E., Ackl, N., Sonntag, A., Ising, M., & Holsboer, F. (2000). Effects of the high-affinity corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor 1 antagonist R121919 in major depression: the first 20 patients treated. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 34(3), 171-181. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3956(00)00016-9