2 Researching protracted displacement: The Protracted Displacement Economies project

Michael Collyer; Fekadu Adugna Tufa; Ali Ali; Shahida Aman; Muhammed Ayub Jan; Priya Deshingkar; Anne-Meike Fechter; Yasmin Fedda; Rajith Lakshman; Eileen May; Rouba Mhaissen; Rebecca Mitchell; Jose Mvuezolo Bazonzi; Ceri Oeppen; Abdul Rauf; Claude Samaha; Tim Schroeder; Ashley South; and Tahir Zaman

Introduction

The length of time for which people live without a long-term solution following forcible displacement remains a major concern, sitting at the intersection of development and humanitarian priorities. The pressing need to find sustainable solutions to crises that have existed for decades should also highlight the imperative to ensure that recent displacement crises are resolved more quickly. The Protracted Displacement Economies project set out to contribute to the analysis of the economic life of people who had been displaced for at least five years, and usually much longer. Research took place in five countries: the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Ethiopia, Lebanon, Pakistan and Myanmar. The project was funded by the UK’s Economic and Social Research Council, through the Global Challenges Research Fund as part of a targeted call focused on forced displacement. It was one of five projects of differing sizes funded under that call. The project began in September 2020 and was due to run for 36 months to September 2023, though we were granted a seven-month extension taking it to the end of March 2024, a total of 43 months. Most of the research was completed within the original duration, the additional seven months were used primarily for outreach and dissemination activities in all locations.

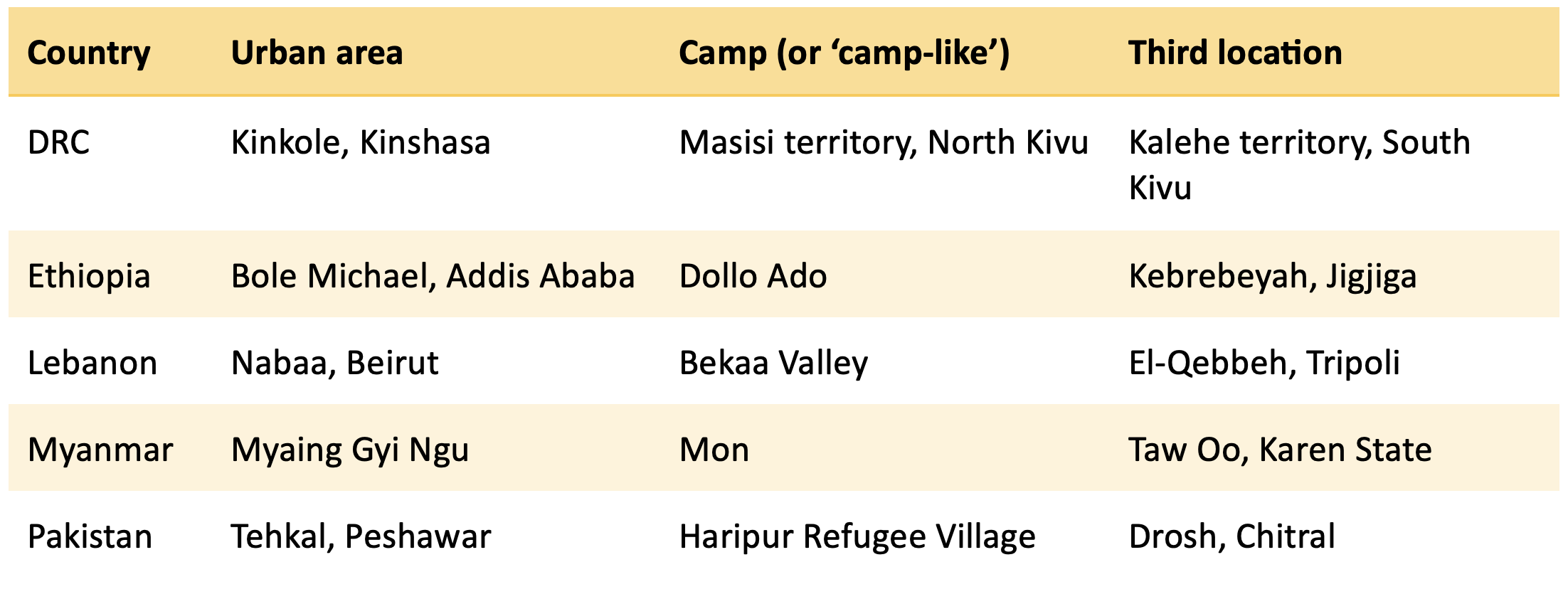

Protracted Displacement Economies set out to develop two significant innovations. First, the project used the frame of the ‘displacement affected community’ to overcome established binary distinctions between host and displaced (Zaman et al. forthcoming). Second, it broadened notions of the economic beyond the purely financial to encompass insights from work on moral economies of care and feminist economics (Ali et al. forthcoming). The project aimed to develop a novel analysis of how communities affected by long-term displacement strategise to support themselves and engage with other economic actors. Research was coordinated from the University of Sussex in the UK in collaboration with partners in the DRC, Ethiopia, Lebanon, Myanmar and Pakistan. Research teams in each country selected three locations in each country where research took place, including at least one camp and one urban neighbourhood in each country. This chapter provides a relatively exhaustive account of the methodological approach and the specific methods employed by the project.

We make a standard distinction between methods, as the fundamental tools and techniques of research, and the wider methodological approach, more closely associated with epistemology, which underpins and guides the methods. For the Protracted Displacement Economies project methods developed and grew during a time of unusual socio-political instability, both at a global level and in all six countries involved (including the UK). We were guided by the methodological approach set out in the initial application, which centred knowledge of displacement around the perspectives of people living in displacement-affected communities and viewed research and researchers as one of multiple economic actors that typically engage in situations of protracted displacement. The resulting methods had to be more than usually flexible in response to the changing political, conflict, economic and regulatory environments. We had always intended to develop some innovations around methods and most of these were enacted. In addition, along with other research going on through the pandemic, we had to develop a new set of approaches for coordinating research at a distance (Mitchell, 2021). Many of the people that we wished to engage in the research were likely to be vulnerable to Covid-19 and vaccination rates remained very low throughout the pandemic in most research locations. The potential to pass on infection added a further layer of considerations to the ethical approach to research, which was fundamental.

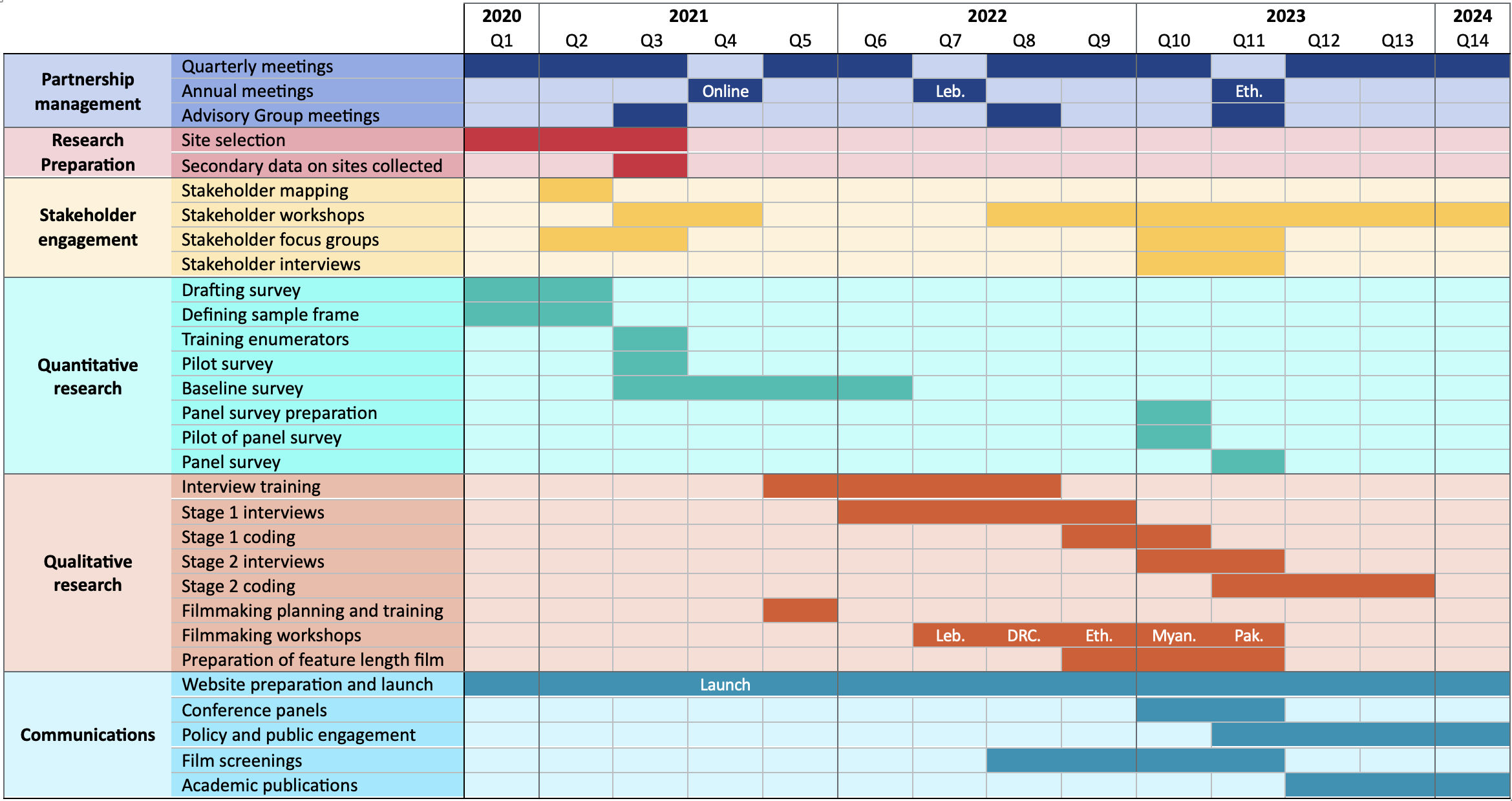

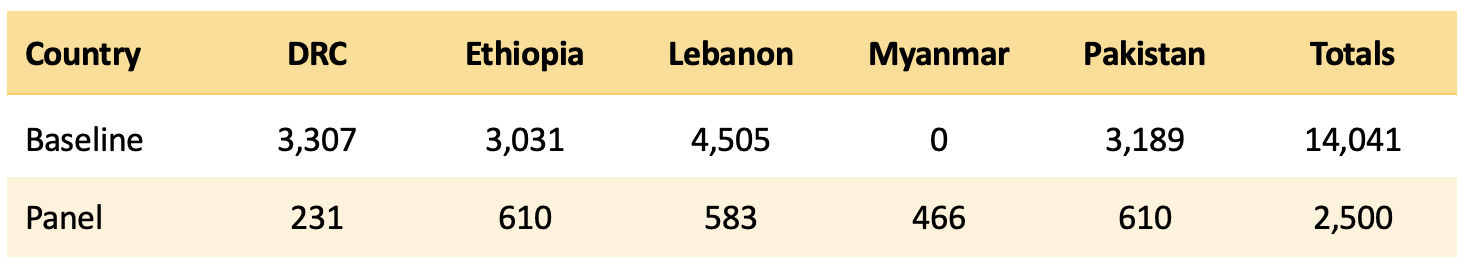

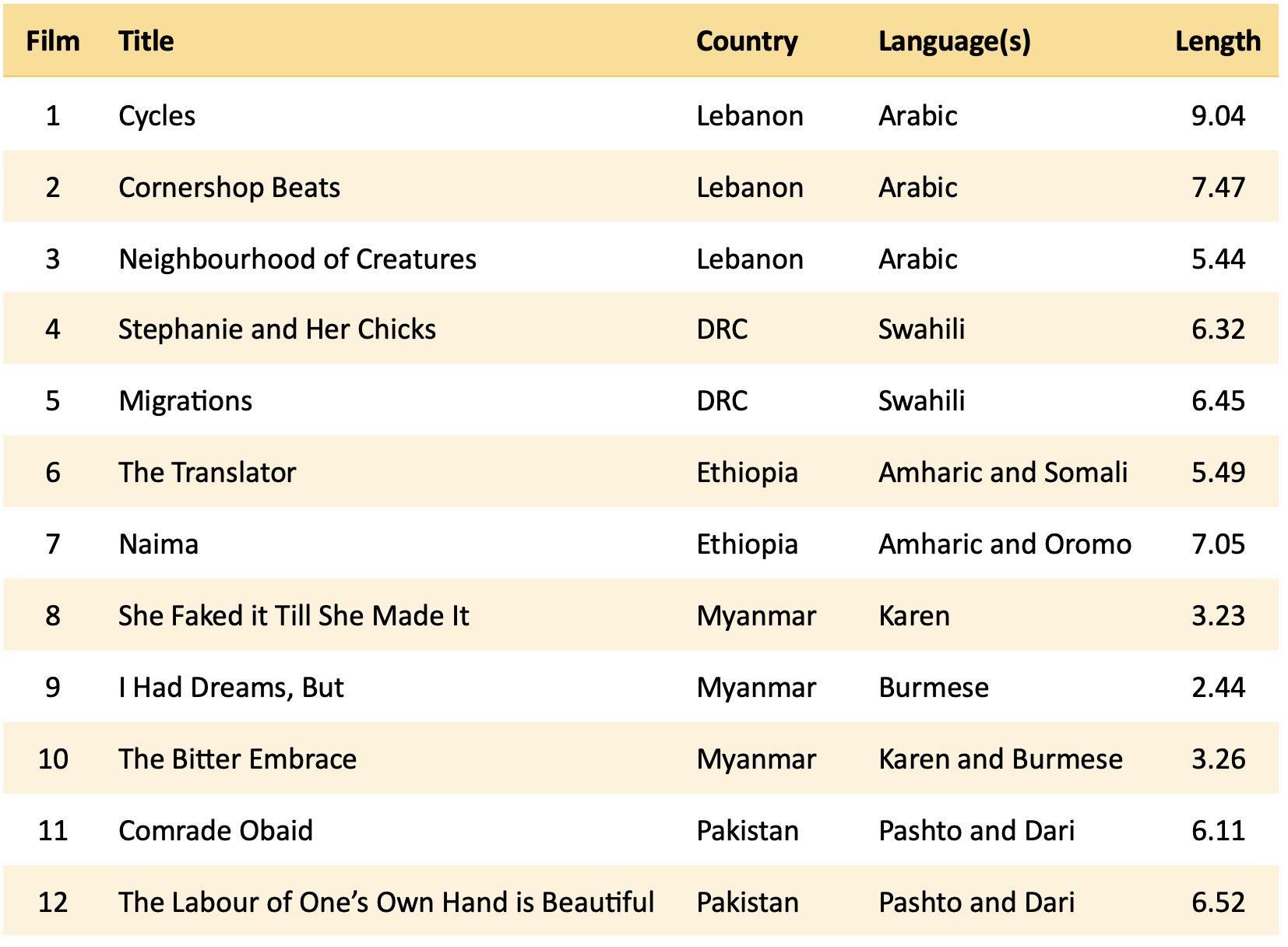

Despite these challenges, the project developed a wide range of methods, sequenced to allow methods to build on and learn from previous approaches (see Gantt chart in Figure 1). Three research locations in each of the five research countries had been selected at the application stage of the project, resulting in a total of 15 research locations. Once research got underway, research teams began to develop contacts in the communities where research would take place. This was limited by Covid-19 and by dynamics of ongoing or newly established conflicts and political and environmental crises in all countries. It was only in Myanmar that the selection of research locations had to be revised entirely, as a result of the military coup in February 2021 and the resulting civil war which continues to engulf the entire country. Community connections developed with multiple focus group discussions in each location, which fed into the design of the large baseline household survey (n=14,041 across the DRC, Ethiopia, Lebanon and Pakistan). The baseline survey took place in all countries except Myanmar. The survey then initiated several rounds of qualitative, oral history-based interviews with residents of research locations. A smaller follow-up panel survey (n=2,034) took place 18 months after the initial baseline survey and also included Myanmar in addition to re-surveys of just over 10% of the original baseline survey in the DRC, Ethiopia, Lebanon and Pakistan. From the middle of the second year and into the third year we organised participatory film-making workshops in all five countries and produced 12 short films, now available online (https://www.displacementeconomies.org/our-focus/core-methods/film-stories-without-borders/).

Collectively, this has resulted in a large quantity of quantitative and qualitative data about our 15 selected research locations and 12 documentary films, all of which we are in the process of analysing and disseminating. A full Gantt chart for the project (Figure 1) shows the timing of this broad array of methods as well as the regularity of meetings. Throughout the project, a meeting of all key researchers was held once a quarter (the ‘executive group’). This was supplemented by three-day annual meetings, the first of which we delayed until the beginning of the second year in the hope that we could hold it in person, though eventually it was online. Our first face-to-face meeting was more than halfway through the project, though by the end of the project international travel had returned almost to normal and we were able to meet without difficulty. This regular pattern of executive and consortium meetings was supplemented by regular contact with an advisory group of experts from academia, government and international organisations.

This chapter provides details of the overall approach and the particular methods used. The remainder of the chapter is divided into six sections. The following section reviews the ethics and epistemology, which closely informed a methodological approach based on the observation that researchers are economic actors too. ‘The shifting research context 2019-2024: Covid-19, conflict and crises’ provides a record of the shifting landscapes against which research unfolded, involving Covid-19-related restrictions, conflicts and wider financial, political and environmental crises in all six countries involved in the research. The remaining four sections turn to the details of the tools and the methods that were used and the forms of analysis applied in each case. ‘Site selection and community engagement’ reviews the various participatory approaches taken through community engagement, focus groups and in some cases direct recruitment of peer researchers. ‘Surveys and sampling’ covers the quantitative approaches taken in the baseline and follow-up panel surveys. ‘Qualitative interviews and analysis’ turns to the qualitative methods of oral history and stakeholder interviews. ‘Participatory film workshops’ explains the context of the participatory film workshops, which took place alongside the other methods. Finally, the conclusion summarises the overall approach and considers dissemination and communication strategies.

Ethics, epistemology and methodological approach: researchers as economic actors

As is to be expected in a project of this nature, the absolute priority was to avoid harm, to both research participants and all members of the research team. Specific threats to individuals in relation to national, regional and local political-economic and particularly conflict conditions varied considerably between and within countries. Here, we relied on the expertise of partners in each country who each have many years’ experience conducting research and were especially attentive to local conditions. In relation to Covid-19, there was much greater commonality and all research locations faced varying degrees of lockdown at different times. Beyond this, the imperative to avoid harm meant that where research could be conducted at a distance we ensured that the resources were in place to do so, and where this was not possible the project was adapted. In some cases, entire sections of the research were abandoned when the judgement was made that they could not be carried out safely, such as the baseline survey in Myanmar, which coincided with the first months of the civil war at a time when all of our colleagues in Myanmar were themselves relocating for their own safety. Research ethics goes far beyond doing no harm and ethical practice was formalised through an ethics review for the entire project conducted at the University of Sussex, supplemented by separate ethical reviews for national approaches in institutions where this was a requirement.

The entire project was based on an epistemological position characterised by two fundamental perspectives: 1. the division of people into particular categories is a politically and socially constructed process, it is not a reflection of naturally occurring groups; and 2. researchers can never be neutral in the research process so engagement must be carefully planned. Both perspectives are now relatively widespread in critical research, particularly on this theme, but both had implications for the conduct of this project. First, social categories are socially and often politically constructed, rather than reflecting any innate or naturally occurring patterns in the ways in which individuals or groups of people behave. Much has been written about distinctions between forced and economic migration that are formalised in the category of the ‘refugee’ (Erdal and Oeppen, 2018). Similarly, the widespread use of the term ‘illegalised migrant’ draws attention to the political process of making people illegal, rather than considering illegality some kind of property of particular types of migrant (De Genova and Roy, 2020).

One of the key categories that we wished to destabilise in this work is the distinction between ‘host’ and ‘displaced’ communities that underlines much research and policy work in this field. As situations of displacement become so protracted that they encompass more than one generation, it is increasingly common for people who have no personal displacement experience at all to be labelled as refugees or internally displaced people (IDPs). Not only is it inaccurate to label someone as displaced if they have not been displaced but in most cases it is normatively wrong, since it helps to reproduce a view that they are out of place or do not belong in the location they have spent their entire lives. The displaced/host distinction is just as problematic from the side of the ‘host’ since it homogenises an inevitably diverse group of people. In many of our research locations, groups of people who have been labelled ‘host’ have their own complex and diverse histories of displacement. In many situations those labelled ‘host’ differ only in very minor details from those labelled ‘displaced’. This is the basis for our use of places, rather than groups of people as the fundamental unit of analysis for all research methods. The 15 research locations were carefully defined according to physical boundaries to identify a specific set of households. These areas deliberately mixed people with different displacement histories in an effort to avoid involving people in the research on the basis of their pre-existing social, political or legal categorisations rather than their lived experiences. These places were termed the ‘displacement affected communities’ and became the core units of analysis for the project. We remained interested in the ways that the distinction between host and displaced operated in each location but we had to find ways of investigating that distinction without using those labels so we did not simply reproduce the same distinctions. This often proved a real challenge, particularly in relation to designing the questionnaire. In a similar vein, the project aimed to expand notions of the economic beyond the purely financial, though here there is a longer history of research to draw upon, a broader vocabulary encompassing care, mutual aid and solidarity (Gibson-Graham, 2003; Spade, 2020) and a relatively widespread acceptance amongst people involved in the research that work for which people are not paid is still work.

In practical terms, the words we chose in presenting the research and in designing research tools mattered both for the understanding of the research and for the conceptual analysis that we wanted to get out of it. This was further complicated by the fact that research was carried out in 14 major languages, including English: Arabic (Lebanon); Somali, Amharic (Ethiopia); Lingala, French, Swahili, Kinyarwanda (the DRC); Pashto, Dari, Urdu (Pakistan); Karen, Shan, Kachin (Myanmar). This does not include other very localised languages or dialects, which sometimes required additional translation. The questionnaire was not translated into all of these languages; in the absence of a baseline survey in Myanmar, the baseline survey operated in Arabic (Lebanon), French/Swahili (the DRC) and Amharic/Somali (Ethiopia). In Pakistan, multilingual researchers operated an agreed pattern of translation from the English version for respondents who spoke different languages. In most cases, interviews were translated directly from the language they were conducted in into English, but in the DRC most interviews were translated first into French and only then into English. Such linguistic diversity is unavoidable in a project of this nature and is one of the joys of conducting this kind of research. Nevertheless, the use of multiple languages has presented an additional challenge in producing research instruments that is not always properly acknowledged, and it necessitates a degree of humility in the analysis of qualitative data.

The second epistemological perspective that has influenced this research is the impossibility that social research can be neutral. Although the perspective of the neutral observer inherited from natural science is almost universally rejected in the (critical) social sciences, detailed consideration of the nature of the engagement with people involved in the research is not so widespread (see Samaha, 2022). The gold standard here is to involve research subjects in the initial conceptualisation of the research. We were not able to do that here. A project of this size required a reasonably detailed justification and methodological outline at the application stage when resources for a consultation with people living in protracted displacement were not available. Researchers in all six countries (including the UK) were involved in the initial conceptualisation and all had plenty of previous experience of working with displaced people and in two cases they had experience of displacement themselves. Nevertheless, this is not a replacement for a participatory framing of the research and we must acknowledge that from the outset this was a top-down project. The ideal of genuine co-production is difficult to fulfil in large international comparative work and the comparison was one of the gaps that we sought to fill which made preliminary discussions with all of the groups concerned an important first step. The project did engage with people living in locations selected for the research from the very first stages and subsequent research materials were shaped around those discussions.

For the first 14 months of the project, we undertook no international travel at all. International travel was highly restricted and even when team members began moving between countries in February 2022, it remained a challenge, involving substantial additional paperwork and regular, usually expensive, testing regimes. The entire research team was not able to meet in person until what had been expected to be the second annual meeting in Beirut in May 2022, 21 months into the 36-month project. Like the rest of the world, meetings shifted online during this period, but it is important to acknowledge that this did not affect the entire research team in the same way at the same time. Apart from variations in digital infrastructure across the research team, different countries were facing a range of shifting regional and national crises which intersected with Covid-19 in different ways.

The shifting research context 2019-2024: Covid-19, conflict and crises

Research in fast-moving conflict environments is always challenging. We are sympathetic to arguments that such instability should not be used as an excuse for a lack of methodological rigour. Even though the methods evolved from the initial planning process, we were guided by a set of clear methodological principles that remained constant and we hope that the methods remain robust. Such a reflexive approach to methods was necessary as the period from the initial application deadline (June 2019) to the end of the project (March 2024) covered more than five years. This period presented a particularly unusual if not entirely unprecedented set of challenges for international collaborative research. The project arose from a funding application written in the first few months of 2019 and submitted to the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) in June that year. We received confirmation of funding in January 2020, when research was arranged to start in April 2020. In April, soon after the start of the first Covid-19 lockdown in the UK, this was delayed until September 2020, when the project officially began. The official end date of the project was September 2023, although we were able to extend this to March 2024 (with no additional funding) to ensure all planned activities had been completed.

The first half of the project was dominated by the global Covid-19 pandemic. At a global level, the situation was easing in September 2020, when the project began. After the Northern Hemisphere summer, the UN World Tourism Organization reported on 10 September that 53% of destinations they surveyed were easing restrictions and it was widely believed that the worst of the pandemic was over (UNWTO, 2020). This was clearly overly optimistic and the first major variant of concern was identified in December 2020, resulting in a renewal of global lockdowns and a rapid reimposition of travel restrictions (WHO, 2023). There was then much more caution about lifting these restrictions a second time. Even with the beginnings of vaccination campaigns in rich countries at the end of 2020 and beginning of 2021, travel restrictions remained in place. In November 2021, UNWTO reported that 98% of destinations they surveyed still had some form of travel restriction in place (UNWTO, 2021). This was broadly the experience of those working on this project and although research was undertaken within countries, under varying restrictions, the first bout of international travel during the project did not take place until February 2022, 18 months into the (initially) 36-month project. Although international travel remained a challenging and extremely bureaucratic process, restrictions slowly eased and we held the first face-to-face meeting in Beirut in May 2022. Although significant crises remain at a global scale, notably in relation to food and energy shortages, the remainder of the project has been relatively unaffected by them. This has not been the case at country level, where national and local issues continued to impact the research teams’ abilities to complete research as initially planned.

Even the UK, one of the wealthiest countries in the world, has not escaped substantial financial difficulties post-Covid-19, the management of which has had a significant impact on the project. The UK had three Covid-19 lockdowns, the first from March to June 2020, and the second and third within a period of shifting restrictions introduced in September 2020 and not fully lifted until July 2021 (IFG, 2022). UK Covid-19 restrictions had little impact on the project, given the international travel restrictions that were in place for longer periods. The project was affected much more severely by the UK government’s decision to make significant cuts in the UK’s contribution to official development assistance (ODA) in March 2021. Boris Johnson’s government cut the ODA budget for the financial year 2021/22 by 21% (just over £3 billion) compared to the previous year, abandoning the UN target to spend 0.7% of gross national income for the first time since 2013 (Loft and Brien, 2022). The Protracted Displacement Economies project is funded through the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF), part of the UK’s ODA commitment that is administered by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI). The UK’s cuts to ODA resulted in a £120 million cut to UKRI’s budget for 2021/22 (UKRI, 2021), which translated into a 60% cut in GCRF budgets for that financial year. In common with most other UK universities faced by these cuts, the University of Sussex allowed us to reduce university costs to zero for the year, meaning that we only had to pass on cuts of 30% to the annual budgets of partners. Given that we had made savings in travel budgets during the 18 months of lockdown, we were able to manage this cut by removing one of the original panel surveys and slightly reducing the overall number of interviews in some locations. We had initially planned a baseline survey and two follow-up panel surveys. The final project has only one follow-up panel survey, but given the Covid-19-induced delays to the original survey, this did not have a substantial additional impact on the project.

In the DRC, national Covid-19 lockdowns were not strictly enforced and across the country conditions varied. Although research had to be delayed, the initial selection of locations was able to take place as the situation stabilised in early 2021, allowing the questionnaire survey to begin in August 2021. Politically, the situation in the DRC remained stable for most of the project. Public disturbances related to protests against the UN peacekeeping force MONUSCO resulted in the brief closure of the border with Rwanda at the city of Goma in June 2022 during the film workshop. The M23 armed group became increasingly active in North Kivu province from October 2022 onwards. This resulted in significant numbers of newly displaced people moving to Goma and the establishment of new IDP camps. In December, M23 came within a few kilometres of Goma before retreating and in February 2023, they took control of the towns of Kitshanga and Rubaya, two of our research locations in North Kivu, preventing the completion of the panel survey in those locations and all research access for the remainder of the project. Otherwise, research in the DRC progressed as initially planned.

In Ethiopia, Covid-19-related restrictions at a national level had limited impact on the development of research. Limited access to mobile phones amongst the target populations meant that the initial survey had to be delayed a little to September 2021 when in-person research was easier. National instability caused by the Tigray war had a greater impact on ongoing research. The war began in early November 2020 in the Tigray region, in the north of Ethiopia. Although the president declared the operation over after only a few weeks, the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) slowly advanced into neighbouring regions. By November 2021, the TPLF was threatening to march on Addis Ababa and fighting intensified as the TPLF allied itself with other regional armed organisations. A negotiated cessation of hostilities was not reached until November 2022. Estimates of the number of people killed are in excess of 100,000, even at the low end, and credible accusations of war crimes have been made against all state and non-state parties to the conflict (Crisis Group, 2022). This conflict covered the period when most of our research took place. In addition to Addis Ababa, research locations had been planned for the Somali region, in the south and east of the country. Although these areas were far removed from the main fighting during the Tigray war, the generalised insecurity in the country inevitably had an impact on the smooth running of the research, particularly when Addis Ababa, where researchers based at the University were located, was under threat of attack. The political situation across the border with Somalia has also been periodically unstable. In July 2022, at least 1,000 members of al-Shabab took advantage of the instability created by the Tigray war and crossed the border with Ethiopia, penetrating over 100km into Ethiopia over a few weeks of fighting. All research in the Dollo Ado camps had to be suspended during this period.

Lebanon has been dominated by a crippling financial crisis since October 2019. The results of this have been dramatic, the currency has fallen by 95% of its value before the crisis, and the costs of basic necessities have multiplied, pushing an estimated 80% of the population into poverty (Human Rights Watch, 2023). This fragility has been exacerbated by multiple additional tensions. In August 2020, the month before the project began, Beirut was severely damaged by a massive explosion at the port. The damage this caused remained very much in evidence throughout the project. In February 2023, a significant earthquake caused widespread destruction in south-west Turkey and Syria, and although Lebanon itself was not directly affected the proximity of the crisis further heightened anxiety, particularly amongst the Syrian population of Lebanon. Hostility towards Syrians has gradually increased as the economic situation has deteriorated. Public opinion, fuelled by media and political accusations has increasingly demanded political action and forced deportations have slowly increased (Human Rights Watch, 2024a). The ongoing destruction of Gaza by the Israeli army has repeatedly threatened to spill over into southern Lebanon as the risk of regular attacks escalating into an Israeli invasion increases. The political hostility towards Syrians in Lebanon combined with the generalised insecurity at the threat of Israeli invasion was most intense after research on this project finished, although it occurred during the project extension and prevented any collective dissemination of results in Lebanon itself.

Of the five partner countries in the project, Myanmar has been most significantly affected by violence against civilian populations, particularly since the military coup of February 2021. Research in Myanmar has therefore changed markedly from the initial plans, insofar as all research was carried out by local research teams only, with the safety and security of researchers and participants of paramount importance. The original project designed was retained as much as possible under these conditions, and some comparative material has been collected. The research locations as initially envisaged were partially amended, as some had become unworkable once the conflict had started and remained so throughout the project. The baseline survey, which was due to begin a few months after the military coup took place, had to be abandoned since even our research partner organisation was forced to relocate out of the country. As the dynamic of the conflict became clearer, the research team were able to draw on contacts with civil society and ethnic organisations from across the border in Thailand. Working with and through these groups, they selected three different locations and began to conduct interviews. By the time of the panel survey in March and April 2023 sufficient trust had been developed to conduct the survey in the Myanmar locations too. The research locations in Myanmar are therefore fully included in the panel survey. We also held a film workshop just across the border in Thailand and were able to produce three short films with groups from Myanmar.

Amongst the five countries involved in this study, Pakistan alone avoided generalised conflict during the period of research. This is not to say that political violence was absent, indeed Human Rights Watch documented hundreds of deaths due to terrorism during 2023 alone (Human Rights Watch, 2024b), including an attack on a mosque in Peshawar, where the research team was based, in January 2023. The broader political situation remains extremely fragile. Pakistan is also vulnerable to extreme climate events; the devastating floods in Pakistan from June to October 2022 resulted in massive loss of life and inevitably affected displaced people involved in the project. The Pakistani government periodically threatened to expel Afghan refugees and although this did not occur during the course of our research, in October 2023, the government gave the estimated 1.73 million unregistered Afghans 28 days to leave the country. This created massive disruption amongst Afghan refugees in Pakistan and several hundred thousand people are estimated to have left. Although the government of Pakistan stated that only unregistered Afghans would face removal, there is evidence of registered Afghans also being threatened (OCHA, 2024).

The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and the subsequent financial crisis were global events that inevitably had a massive impact on the entire project. But it is clear from this brief review that Covid-19 is only part of the picture. All five of our partner countries have faced political violence, financial breakdown and natural disasters on a national scale. These have exacerbated insecurity, particularly for the poorest, and in some cases have resulted in very significant loss of life. In all cases, displaced people have been amongst the worst affected, as the most marginalised in each society. In some cases, most obviously in Lebanon and Pakistan, refugees have been directly targeted for forced deportations. It is worth restating that there is no evidence that refugees have made any significant contribution to the problems that they are blamed for, but, as elsewhere in the world, refugees are easy scapegoats to distract attention from wider political failings. In addition to widespread protracted displacement in all research locations, there has also been substantial new displacement. In some cases, such as in Pakistan, this has brought newly arrived groups of refugees into contact with extremely longstanding refugee populations. In other cases, such as in the DRC or Myanmar, long-term IDPs have been forced into further displacement. All of these situations underline the tremendous fragility of the lives of displaced people and highlight how the economies constructed in protracted displacement can so easily be disrupted by further crisis. This is ultimately the focus of the research, so the methods envisaged for the project have had to work around this ongoing, substantial disruption to the displacement-affected communities where research has taken place.

Site selection and community engagement

The precise selection of sites in this project took place once the project funding had been approved. At this stage, we already had a fairly detailed outline of the approach that we intended to take and although, for reasons discussed in the previous section, this was of necessity flexible, it remained a set of guidelines. We had also identified the types of research location where we planned to conduct research. In order to generate significant intranational comparison and allow connections between different countries, we set out to select a similar set of three locations in each country. These were a camp setting, an urban neighbourhood and finally a third location to allow for national specificities (Table 1). In order to allow for meaningful comparison, locations of roughly comparable size were selected for research. In all contexts, we were aiming to identify areas of roughly 10,000 households. In some cases this meant that multiple camps were selected for the ‘camp’ location since existing camps were very small. In others, this meant sub-dividing a recognised spatial unit, such as a neighbourhood, which was much larger. In all cases, we first defined areas and undertook research in those areas, rather than identifying a particular population to focus on. We referred to this as a ‘place-based’ approach to research design.

In terms of camp locations, there was considerable variety in the contexts chosen but also clear commonalities. The five camps chosen were all significantly institutionalised settings that were for the exclusive use of people defined as displaced, though in many cases those not defined as displaced lived in fairly close proximity. Camp residents are defined as either IDPs, refugees or in some cases both. The level of institutionalisation and the nature of the institution responsible varies, but all camps were dependent, at least initially, on an external actor for the allocation of resources, including land and shelter. and in some cases for ongoing support. Given the protracted nature of the situations, that institutional actor has in some cases left with little trace apart from perhaps a sign board, such as Mungote IDP camp in the town of Kitshanga in North Kivu province, DRC. In other cases, such as the Dollo Ado camps in south-east Ethiopia, support from institutions, mainly UNHCR, is ongoing and significant. The size of camps also varied. The largest was Dollo Ado, where at the beginning of the research process over 170,000 people lived across five camps, though research focused on a more manageable area of about 10,000 households. The smallest were the individual units dispersed around the Bekaa Valley in Lebanon where camps are located on the property of pre-existing houses and each unit may be as small as 100 people, although there are many such units and a boundary was identified to include both Syrian refugees living in camps and other residents who are mostly Lebanese.

Urban neighbourhoods again vary significantly, though all are identifiably urban. Neighbourhoods were deliberately selected to include a significant presence of refugees or displaced people. Given the size of some neighbourhoods, there was a need to identify a clear boundary, often smaller than the recognised neighbourhood, since neighbourhoods often housed several hundred thousand residents – too many for meaningful research. Again, for the purposes of sampling, areas of approximately 10,000 households were selected. The third locations varied from country to country and were selected by research teams to reflect the variety of situations of protracted displacement in the country. In Lebanon, the third location was a second urban neighbourhood, reflecting the high level of urbanisation generally in Lebanon. In the DRC, Ethiopia, Pakistan and Myanmar the third location was a rural area where displaced people have self-settled (away from institutionalised camp settings) or semi-institutionalised camp. Following confirmation of these details a full ethical review of the project was undertaken at the University of Sussex. In addition, where partners were universities (Universities of Kinshasa and Goma, DRC; University of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; and University of Peshawar, Pakistan) and so had access to their own ethical review procedures, we also used these. In addition to broadening the overall ethical evaluation, this meant that national research plans were examined by people with knowledge and expertise to consider the particular localities where research was to take place, in addition to the broader context. Once three locations had been selected in each country, and the ethical reviews had been approved, the initial stages of research began.

The research methods are broadly divided into participatory, quantitative and qualitative. The research design was based on careful consideration of the best way to sequence these three distinct approaches. The initial approaches were as participatory as we could manage in a project of this size and design. This was limited by the fact that when research teams initially approached people living in the areas that we hoped to include in the research, the broad direction of the research was already set. Nevertheless, the initial range of approaches are described as participatory as they set out to investigate how residents of the selected areas thought about the topics of research with as few impositions from the research team as possible. Three broad stages were followed by teams. First, a series of community meetings were held to obtain necessary permissions to conduct research in the selected areas and to inform residents as far as possible about the nature and duration of the research. Second, in some locations (particularly those in more inaccessible areas) some researchers were recruited from the local area – this complicated certain logistics, but incorporated researchers with a real understanding of local conditions into the research team. Third, multiple focus group discussions were held in each site to set out broad areas of discussion and identify the key themes for subsequent stages of research.

Community meetings were a vital first stage in the research in all areas. In Lebanon and Myanmar, the main research partners were community organisations who worked at least partially in each of the research locations. Here it was especially important to differentiate the research from other community support activities that the organisations were involved in. In all cases, the research allowed specific individuals to be employed to limit any confusion. In Pakistan and the DRC, research took place in locations where members of the research team had previous experience of working. It was only in Ethiopia where the research required new contacts to be made. This process involved meeting with local governmental authorities to explain the process of the research – in some cases, such as Pakistan, detailed state-level permission was required before these initial contacts could be made. Official government contacts were necessary to ensure that researchers faced no risk conducting the research and to reassure all those involved in the research that the research was undertaken with local government cooperation. In some situations, displaced people had good reason to be wary of state authorities, but here it was even more important to be able to reassure them that those authorities had approved the research. Once local government approvals had been received, we presented the research to civil society and community-level organisations. Where necessary (such as in the DRC), we also sought approval of customary authorities. We met as many people as possible in each location to ensure maximum awareness of the research before it began.

Following these initial meetings, where research sites were particularly inaccessible, most teams chose to recruit locally based researchers. In the DRC, this was the case for locations in North and South Kivu, which were managed from the University of Goma, although they were a full day’s drive from Goma. In Ethiopia, research in Kebribeyah camp was managed by a colleague at the nearby Jigjiga University, rather than directly from Addis Ababa, although research in Dollo Ado camps had to be undertaken in extended visits from Addis Ababa. In Myanmar, the difficulties of crossing the border and the collaboration with regional and ethnic groups meant that some of the research was conducted in direct collaboration with these organisations. In Pakistan, research in the inaccessible area of Chitral was partially managed by a resident in one of the camps. It was only in Lebanon, where distances are small and one of the organisations we worked with had offices in the Bekaa Valley anyway, that no locally based organisation was present.

Once the relevant approvals had been received and local government and civil society groups had been informed, the first stage of research was focus group discussions. Although focus groups are inevitably framed by the researchers’ initial questions, they offer a chance to begin to understand the ways in which people view the themes of the research, unconstrained by specific questions. Crucially, they also provide an opportunity to investigate the specific words that are used in relevant languages when discussing the core research concepts. Both the breadth and context of the discussion and the specific language of the research themes were essential for the research to develop the next stage of devising the baseline survey, which had to consist mostly or entirely of closed questions. Focus groups are therefore considered part of the ‘participatory’ part of the research methods. In each of the 15 research locations at least two focus groups were held: one for women only and one for anyone (which in practice was almost exclusively men).

Research teams were encouraged to hold additional focus groups if they considered that any groups would be excluded from that initial overall division. This worked differently in different places. In the DRC, a third focus group was held in each location to include young people (a category which roughly corresponded to ‘under 25’ but was modified according to marital status) giving a total of nine. In Lebanon, four focus groups were held in each location organising Lebanese and Syrians into two different focus groups each. Even though Lebanese and Syrians speak the same language, the team thought that they would feel constrained to discuss issues around displacement in a nationally mixed context. This resulted in 12 focus groups in Lebanon. A similar approach was taken in Pakistan with four groups for Afghans and Pakistanis in two of the three locations (although not the camp location), giving a total of 10. In Ethiopia separate national groups were not considered necessary due to the density of cross-border family ties, so there were only six. In Myanmar, additional focus groups were held in different local dialects, since even in one location people displaced from different parts of the country spoke different languages. This resulted in six different focus groups in one location, although only three and two in the other locations, giving a total of 11 for Myanmar. Overall, there were 48 focus group discussions across the 15 research locations.

Focus groups were organised around four questions, which were framed as broadly as possible in order to avoid suggesting ideas to people. The first question asked participants to list all sources of support that people relied on in the neighbourhood. These were discussed in detail and facilitators noted the exact words that were used for each, to inform translations of the survey questionnaire. All sources of support were put on a board as words or pictures, and the second question was an exercise to rank sources from the most to the least preferable. The third question probed to ensure that all available sources of support were included, to make sure that external support from NGOs, UN or government institutions, community organisations, support between neighbours and friends, and intra-household support were all part of the discussion. Finally, the last question investigated the ways in which all the sources of support were valued in the neighbourhood. It asked whether participants thought the way that support was valued was acceptable or should be changed. This was a way of raising issues related to the gendering of different forms of work and the (unpaid) care economy. Results of the focus groups, in terms of both core concepts and the language used to describe them, were fundamental to the design of the baseline survey, which sequentially, was the next stage of research.

Surveys and sampling

Two surveys were undertaken during the project: a baseline survey involving just over 14,000 households in all countries except Myanmar was completed between August and October 2021. A follow-up panel survey included a target of 20% of the respondents of the original survey (so just over 2,800) though it was only in Ethiopia and Pakistan that this target was reached (Table 2). All the quantitative data collected for the Protracted Displacement Economies Project has been anonymised and deposited in the UNHCR microdata library, and is available to interested parties here: https://microdata.unhcr.org/index.php/catalog/1252. The panel survey was conducted between March and May 2023, so approximately 20 months after the original survey. The DRC survey was significantly reduced due to the ongoing conflict in the east of the country. The town of Kitshanga, in North Kivu, including the camp of Mungote, was occupied by the armed group M23 at the time of the second survey and the majority of the population of the town was newly displaced (or re-displaced) so it was not possible to include this location in the panel survey. A total of 20% of the original survey population in the other two locations was included, however. In Lebanon, the research process was affected by the deteriorating situation of deportations of Syrian nationals. Since this did not appear likely to improve within timeframe of the survey the survey was curtailed with approximately 15% of the original households. The initial survey that mirrored the panel very closely was conducted with 466 households in Myanmar at the same time.

Questionnaires were broadly the same in all countries involved in each survey. The Myanmar survey was based closely on the other two surveys, although it was adapted significantly to reflect the fact that it was the only survey we were able to conduct in Myanmar. In the baseline and panel questionnaires a small number of questions were added by most country teams that were specific to their own country, but more than 95% of questions formed a core common to all four countries where they were undertaken. The questionnaire for the panel survey is broadly the same as the questionnaire for the baseline survey with a modified household roster and a small number of new questions. Both surveys were undertaken by trained enumerators, asking questions in person. In all cases, we used the open access software package Kobo (https://www.kobotoolbox.org). This allowed questionnaires to be completed online or if carried out in an area without an internet connection, to be uploaded as soon as a wifi connection could be reached. The baseline questionnaires were translated into Arabic (for Lebanon), Amharic and Somali (for Ethiopia), Swahili and French (for the DRC), and Pasto (for Pakistan). The Myanmar survey was translated into Burmese and administered in other languages according to agreed translation guidelines.

The baseline survey was designed to collect basic information on the economic life of the household, using internationally comparative measures. Given the focus of the project, it was necessary to capture information about both financial and non-financial connections within the household and within the neighbourhood. The survey begins with a household roster of basic demographic information for all members of the household, in addition to their economic role in the household in terms of income generation and care. This was followed by six significant sections: 1. change of location; 2. livelihoods and support; 3. collective support and mutual aid; 4. expenditure; 5. credit and debt; 6. relations between displaced and non-displaced people. Change of location covered a brief history of displacement of anyone in the household, in addition to post-displacement movements, attempts at return or onward migration. Livelihoods and support produced an inventory of all sources of financial and non-financial support received by the household, including employment but also cash and non-cash assistance. Collective support and mutual aid focused specifically on intra-household levels of care work but also on financial and non-financial sources of exchange with neighbours, as well as means of coping with poverty in the household and neighbourhood. Expenditure involved a full account of spending over the previous month. Having recognised the significance of debt in focus group discussions, the fifth section explored credit and debt in more detail, collecting information about savings in the household, as well as who has control of those savings, the extent to which the household uses official banking services and, finally, detailed questions about various debts owed by individuals in the household. The final section considered relations between displaced and non-displaced people, providing some information on how this boundary around the definitions of displacement are managed. The panel survey followed the same sections, with a modified form of household roster to allow some tracing of changes within the household.

The full questionnaire took just over an hour to complete. Given the economic focus of the project, a key principle of the research was that all participants would be compensated for their time. Different country teams managed this in slightly different ways, with different amounts, or in some cases non-cash support, such as phone credit. This was extended to all other methods on the project. In some cases, this is seen as controversial, although we took it as an ethical imperative to recognise the fact that we were expecting people with very limited resources to give up their time (and in some cases forego income) in order to participate in the project. We have a separate publication on this (Collyer and Ali, 2024).

The baseline survey followed a systematic sampling approach. Following initial qualitative surveys of the area to be incorporated into the sample, in the form of transect walks, individual households were selected on a systematic sampling basis, usually involving the selection of every fifth house, although this was modified in different contexts, depending on the total number of households in the area to be sampled. In general, we were able to sample between 1% and 5% of the total number of households in any defined sampling area. Once a household had been selected, the individual who responded to the questionnaire was left to the discretion of the members of the household present, but in all cases the details and position of the person who responded were noted. A final question in the baseline survey asked if individuals would be willing to be contacted again for a follow-up survey. It was gratifying that the vast majority of respondents (96%) said that they would be willing to be involved in similar research in the future and provided address details and a telephone number where this was available for the purpose of making contact for the later survey. Storing contact information directly in Kobo, which was then uploaded to a secure server as soon as possible and deleted from the tablets or phones that were used for the survey, enabled a degree of security around the storage of this information.

Sampling for the panel survey was undertaken on the basis of a random sample of those people who had expressed a willingness to be involved in follow-up surveys. The target of 20% of the initial sample was over-sampled, to allow for households where no one was present or it was impossible to trace them. The use of Kobo allowed survey teams to be supplied with QR codes that could be scanned just before interview to reveal details of the initial survey. The QR codes provided some protection through anonymity for the respondents of the initial survey and meant that if data were discovered it would be inaccessible to anyone except those with an approved QR reader from within Kobo Toolbox. The panel survey began by checking carefully that the survey team was in the same household as before. The survey team made every effort to speak to the same individual within the household who had completed the baseline questionnaire 18 months earlier. Once this had been established, the questionnaire turned to the household roster, going through the members of the household one by one, as they had been reported in the baseline survey. Both surveys were initially analysed in Kobo with subsequent statistical analysis in the statistical programmes R and SPSS.

Qualitative interviews and analysis

The main qualitative component of the research involved interviews, which were sequenced to begin between the two surveys. Interviews were of two types: long, unstructured interviews with residents of displacement-affected communities, and stakeholder interviews with particular key informants that were much more directed and targeted. Resident interviews took place in three waves, the first immediately after the baseline survey, the second approximately six months later and the third immediately before the panel survey. The same individuals were involved in the three waves, but the number of people was reduced, to allow subsequent stages of interviews to be much more focused and in-depth. The first wave of interviews targeted 150 people in each country, 50 in each of the three sites. The second wave followed up with between 40 and 50 of these people in each location. By the time of the third wave of interviews, the focus had reduced to those involved in the displacement narratives publication, a broad selection of 10 people from each country who had been interviewed three times in all. Given disruptions in all contexts, these targets were not always met. In total, we conducted 692 resident interviews, split across the three periods of research, and 68 stakeholder interviews.

Interviews with residents were based on oral history methods and were as unstructured as possible in order to allow interviewers the opportunity to explore whatever themes individuals wanted to talk about most. Interviewees were selected on the basis of those who noted in the questionnaire survey that they would be willing to be interviewed. Based on this population, sampling was purposive to reflect a mix of genders, ages and experiences of displacement. In a limited number of situations, residents who had not been selected for the questionnaire were selected for interview because of the position they occupied. For example, in a few cases local shopkeepers were interviewed, but where they lived in the neighbourhood, they were interviewed as residents, rather than as stakeholders. These cases were exceptional, however, and in almost all cases interviewees had undertaken the baseline survey and were therefore familiar with the themes of the research.

Each team conducted a series of pilot interviews, which were recorded and transcribed and then discussed as the basis for a series of training sessions with each team of interviewers. A check list was devised to identify key themes for the interview to follow with sample prompting questions for each but the focus for each interview was to follow the interests of the resident and let them talk. In the most successful interviews, this resulted in lengthy, free-flowing discussion. Less successful interviews resemble questionnaires with open-ended responses – essentially a series of questions with very short answers. In successive stages of interviewing, those people who enjoyed speaking were followed in more detail, though this sampling strategy was shaped to reflect an approximately equal share of men and women, a variety of ages and a range of experiences of displacement, from both those defined as ‘host’ and ‘displaced’. Stakeholder interviews were much more directed than resident interviews, although precise questions varied with the particular context of the stakeholder. Both resident and stakeholder interviews were recorded, transcribed and translated in full.

Resident interviews (in English translation) were analysed in NVivo. A small team from multiple research locations worked on a system of coding these interviews which was then applied across all interview locations. This involved 29 main codes and an additional 12 sub codes. Each country also had a set of specific issues that were of relevance only to those interviews, which had a separate code, so an additional five. This resulted in 46 total codes. As always in these situations, this involved a compromise between the huge range of potential codes that each individual involved in the project would have liked and a continual attempt to make a workable, relatively easy-to-use set of themes into which interviews were categorised. Categorisation of all interviews on this basis is now complete. Stakeholder interviews have not been interviewed as, given the smaller number and the focused questioning, these are more easily accessible based on the position of the person being interviewed and this is how they have been classified. The limited final selection of interviews will be brought together into a source book that contains interviews only.

Participatory film workshops

A key element of the research process was the production of a series of short, participatory films focused around the key project themes. A short workshop was held in each country in which a small number of residents of the displacement affected communities where research took place received training and then produced films of between three and seven minutes long. These films ran alongside other methods but formed distinct outputs, unrelated to surveys or interviews. They therefore followed a distinct timetable and did not need to be sequenced with other methods. All workshops were run by Dr Yasmin Fedda who supervised each stage of the process. In the DRC, Ethiopia, Lebanon and Pakistan, the workshops were held in person. In Myanmar, the workshop was held online, although some of the UK team attended in person to facilitate the process. The Lebanon film workshop was the first, in March 2022, and the final workshop was in Pakistan, in April 2023. These workshops resulted in 12 short films, which are now freely available on the project website (Table 3). Each of the country chapters contain descriptions and links to the relevant films.

Workshop participants were selected in advance from across the neighbourhoods (or camps) where research was taking place. Based on residence in a research area and a degree of experience with films, between six and 10 people were invited to join the workshop. A total of 36 filmmakers were involved in producing films. All residents of the areas where we were conducting research were very familiar with protracted displacement and many filmmakers were themselves displaced. Their filming experience was generally very limited, but given the short duration of the workshop, some familiarity with filmmaking, even if only on mobile phones, allowed relatively polished films to be produced. All participants were paid for their involvement in the filmmaking and presented with a certificate of completion at the end. Only one film workshop was held in each country and in some areas this meant that a choice of locations had to be made, since it was not practical for participants to travel to all sites. This was the case in the DRC, where the workshop was held in Goma and only covered North Kivu. In Ethiopia, the workshop was held in Addis Ababa and only covered the experience of long-term displacement in the capital, since travel to the Somali region was too time consuming. In Pakistan, filming focused on the city of Peshawar and immediate surroundings rather than the more distant research locations of Haripur and Chitral.

Each workshop lasted between 10 and 12 days and covered three segments: training, filming and editing. Training lasted either two or three days and began with a discussion of storytelling and the theoretical considerations of making films. Filmmakers were formed into two or three teams of three people each, and on the second day, people familiarised themselves with filming equipment and practised filming. This first stage of the workshop finished with a discussion of ideas that each team had for films, led by Dr Fedda and involving a wide range of members of the local research team. Out of this discussion, teams selected a main idea and a reserve to start filming. The next stage of the research involved filming the material to follow the initial idea through. This lasted three days. If the initial idea proved unworkable in practice, filming teams developed a new strategy, but given the limited time this was a challenge. The final stage of the workshop focused on editing, which lasted four days. Each workshop ended with a screening of the films that had been made, usually involving other residents of the neighbourhood who provided feedback. These rough cuts were completed back in London with professional finishing, such as sound and colour balancing.

In all countries, films have been shown to multiple audiences, including residents of the neighbourhoods where the films were produced and stakeholders from relevant organisations. As the process of filmmaking went on, films from other locations were also shown at these events to allow residents of displacement-affected communities to experience the ways in which people faced with very similar challenges in very different locations have been able to get by. All films have now been combined into a single full-length film called ‘How We Work’, which brings together all of the films with a series of short animations between each film. This film has been screened online, with all 36 filmmakers invited to take part. It has also been screened in London. Screenings of all films are continuing.

Conclusion

As displacement at a global scale affects more and more people for longer periods of time, the most important lesson from the Protracted Displacement Economies project is to emphasise the instability of lives lived in displacement. The five countries selected for this study were not chosen for their political instability but for the presence of very significant numbers of refugees and IDPs who had been displaced for extended periods of time. Nevertheless, in all five countries people bore the brunt of massive financial disruptions and all countries experienced significant environmental and political disturbances. This resulted in substantial loss of life and significant additional displacement, although in all contexts the poorest, who typically included those already displaced, were worst affected. In many cases displaced people were also scapegoated for wider political failings – and received increasingly harsh treatment as a result.

The methods of the project had to work around these changing dynamics. Although methods themselves were flexible – resulting from shifting political, conflict, environmental and financial dynamics – the overall methodology remained consistent. Methodologically, the project prioritised the perspective of displaced people, through ethnographic, qualitative and quantitative means, and including participatory film work. This was contextualised with archival work on existing context and policies, as well as multiple stakeholder interviews, but the methods responded to the research focus of investigating how economies work for and with displaced people. The wider social context of the displacement-affected community and the wider economic context, going beyond the purely financial, were important parts of this.

There were multiple meetings with stakeholders in each country at every stage of the research and at a global scale. This has included final dissemination meetings to discuss the end results, although in some places these had to be managed carefully given the rising hostility to displaced people in a number of national contexts. We have also held multiple film viewings in each location, including with the community groups involved in making them. In-person meetings are now being replaced with publications, and this book supports that activity by providing a full-length account of the methods and key results that that work can draw on. All publications will be listed on the project website – www.displacementeconomies.org.

References

Crisis Group. (2022). Turning the Pretoria deal into lasting peace in Ethiopia. https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/horn-africa/ethiopia/turning-pretoria-deal-lasting-peace-ethiopia

Bivand Erdal, M., & Oeppen, C. (2018). Forced to leave? The discursive and analytical significance of describing migration as forced and voluntary, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(6), 981-998, https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1384149

De Genova, N., & Roy, A. (2020). Practices of illegalisation. Antipode, 52(2), 352-364. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12602

Gibson-Graham, J. K. (2003). Enabling ethical economies: Cooperativism and class. Critical Sociology, 29(2), 123-161. https://doi.org/10.1163/156916303769155788

Human Rights Watch. (2023). World Report 2023: Lebanon. Events of 2022. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2023/country-chapters/lebanon

Human Rights Watch. (2024a). Lebanon: Stepped-up Repression of Syrians. (April 25). https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/04/25/lebanon-stepped-repression-syrians

Human Rights Watch. (2024b). World Report 2024: Pakistan. Events of 2023. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2024/country-chapters/pakistan

Institute for Government. (2022). Timeline of UK government coronavirus lockdowns and measures, March 2020 to December 2021. https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/2022-12/timeline-coronavirus-lockdown-december-2021.pdf

Loft, P., & Brien, P. (2022). Reducing the UK’s aid spend in 2021 and 2022, House of Commons Library. (February 12). https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-9224/CBP-9224.pdf

Samaha, C. (2022). Emotions in field work. (June 15). https://www.displacementeconomies.org/emotions-in-field-work/

Spade, D. (2020). Mutual Aid: Building Solidarity During This Crisis (and the Next). Verso Books.

UNWTO. (2020). More than 50% of global destinations are easing travel restrictions – but caution remains. (September 10). https://www.unwto.org/more-than-50-of-global-destinations-are-easing-travel-restrictions-but-caution-remains

UNWTO. (2021). New Covid-19 surges keep travel restrictions in place. (November 26). https://www.unwto.org/news/new-covid-19-surges-keep-travel-restrictions-in-place

UK Research and Innovation (UKRI). (2021). UKRI required to review Official Development Assistance funding. (March 11). https://www.ukri.org/news/ukri-required-to-review-official-development-assistance-funding/

World Health Organisation (WHO). (2023). WHO’s Covid-19 Response. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/interactive-timeline#event-227