6 Myanmar

Angela Aung; Anne-Meike Fechter; Eileen May; Mi Kun Chan Non; Jasmin Paw; and Ashley South

Country context

Myanmar is a country of 55 million people with a long history of conflict-induced displacement to areas inside as well as outside the country. More than 1.9 million are estimated to have been driven into exile, mostly in neighbouring countries, including 1.6 million Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh (UNHCR, 2021). About two-thirds of the population come from the majority Bama group; the rest of the population is made up of dozens of ethnic minority (or ‘nationality’) communities.

Relationships between communities, civil society networks and armed actors in Myanmar are complex, contested and variable. Since the military coup of 1 February 2021, which brought the State Administrative Council (SAC) junta to power, the people of Myanmar have struggled to resist military control and violence. Many of those opposing the junta have come from civil society, or ethnic armed organisations (EAOs), many of which have been struggling against the Myanmar military for decades.

In August 2022, a coalition of local organisations found that 1.5 million people had been forcibly displaced and at least 3,500 killed by the Myanmar army since the coup. There were 500,000 internally displaced people (IDPs) in the south-east of the country alone (KNU, KNPP, CNF and NUG Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs, 2020). These include ethnic nationality Karen and Mon communities, where the Protracted Displacement Economies (PDE) and local partner groups are undertaking research under difficult and dangerous conditions. In 2023, the protection environment further deteriorated – with massive Myanmar army (and air force) strikes against civilian communities across the country. The latest, conservative data from UNHCR estimated in January 2024 that over 2.6 million IDPs are trying to survive inside the country, more than 2.3 million of whom were forced to flee since the coup (UNHCR, 2024). Among the IDPs, the main focus of this research, women and children, particularly unaccompanied minors, LGBTQ and religious minorities, are particularly vulnerable. Although communities often support differently abled people well, those with disabilities, including landmine victims, are at risk of marginalisation. For this project, therefore, the safety of researchers and informants was particularly important.

The impacts of Covid-19 in Myanmar have exacerbated the increasingly felt challenges posed by climate change, including rising temperatures and erratic rainfall patterns. Even before the coup, communities and local economies in Myanmar were often highly stressed. One of the main themes of the PDE project consists of the important roles of membership to and mobilisation of faith-based and ethno-linguistic networks. These are key elements in ‘social capital’ – resources that allow individuals, families, communities and ethnic nations to absorb, adapt to and sometimes transform the hazards they experience. For most communities in Myanmar, protection begins at home – with civil society organisations (community service organisations (CSOs)), national non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and EAOs all playing important roles. With very limited international humanitarian access, local actors are at the forefront of protecting basic livelihoods, human rights and the survival of communities. Not surprisingly, given the SAC’s continued attacks on civilians, including several well-documented massacres, many are struggling to sustain basic security and livelihoods. In most of the research areas, livelihoods are primarily based on subsistence agriculture, supplemented by some access to markets.

Following the coup, several of Myanmar’s longer-established EAOs have provided shelter to a new generation of Burmese democracy activists from the towns and cities who fled the SAC’s violence, but did not given up the struggle for democracy and human rights. Inspiring partnerships have developed between EAOs and ‘Generation Z’ and other civil society activists, newly politicised and empowered by their opposition to the junta.

Another key set of stakeholders are rural communities. Even before the coup, there were at least a 250,000 IDPs in the country (ibid.). This is testament to the failure of a previous peace process, which began in 2012 but was not adequately supported by the National League for Democracy (NLD) government that assumed power in 2016. Since the NLD-led government was ejected by the SAC in February 2021, things have gone from bad to worse for many of Myanmar’s ethnic communities.

In south-east Myanmar, organisations such as the Karen National Union (KNU) and NMSP are perceived by local communities as protecting their ethnic homelands from incursion by the Myanmar army. In addition to providing a relatively protected space, many of Myanmar’s EAOs provide health, education and other services to conflict-affected communities, including during the Covid-19 crisis. While international donors were relatively generous, the Myanmar government and army provided little support for these efforts.

The roles of civil society actors are therefore particularly important. Many civil society groups work in partnership with EAOs – or in other cases, operate ‘below the radar’ – to deliver life-saving services, as well as working with communities where possible to support local livelihoods. They also play important roles in advocacy, documenting and speaking out to address the plight of communities. Ethnic CSOs often work in partnership with EAOs, helping to develop policy and implementing programmes to support and protect communities. In most cases, these local organisations have access to conflict-affected communities, whereas international agencies do not. Gender dimensions are important to these dynamics, with women under-represented in EAOs, but often playing important leadership and other roles in civil society.

The research process

The PDE project overall underwent significant changes as a result of Covid-19 and also because of funding budget cuts imposed by the UK government. In addition, serious security threats following the February 2021 coup caused a major re-assessment, and selection of some new research sites. The country was plunged into chaos, with systematic violence and human rights violations inflicted upon large sections of the population by the Myanmar army and junta. As well as direct threats to life in human security, the coup significantly limited the areas where we could work. Nevertheless, the Myanmar team proved resilient, working with local partners to identify three research areas in the south-east where research could still be undertaken. Mainly due to security concerns, the large-scale quantitative survey was not implemented in Myanmar. Nevertheless, a smaller household quantitative survey of 150 households was carried out in each location, for a total of around 450. The qualitative research component was undertaken as planned.

Our longstanding relationships and trust with both EAOs and local authorities granted us a significant advantage, enabling smooth access to communities and seamless implementation of our research activities. Obtaining permission from the EAOs, particularly in the areas they administer, was crucial for conducting research within their territories. Their active involvement extended beyond providing feedback on our questionnaire; they offered invaluable insights into local dynamics and recommended suitable research villages that aligned with the community’s specific needs and sensitivities. Moreover, these collaborations bolstered the credibility of our research, fostering increased community participation and support.

In our research approach, we prioritised a conflict-sensitive approach to ensure that our work did not inadvertently harm the communities. Anonymity was maintained by omitting respondents’ names, and our local team ensured that participants fully understood the research objectives and processes. As a result, the respondents were generally enthusiastic about participating in the research, a response facilitated by the effective networking skills of our local partners and our positive relationships with community leaders and gatekeepers. This approach fostered trust and confidence in our research efforts and encouraged active community involvement.

Site selection and community profiles

Research was undertaken in three locations, illustrating different modes of displacement, and varying economic strategies and coping mechanisms. Focusing mostly on two ethno-linguistic groups, Mon and Karen, allowed for exploration of dynamics among and between actors in the three different locations, across which families may be spread. Two of the research locations are under the authority of EAOs. The three locations were selected to illustrate the diverse settings in which long-term-displaced people live, the challenges they face and the resourceful strategies often adopted. In detail, they include:

Taw Oo (Toungoo) district (KNLA 2 Brigade), located in northern Karen state

This northern Karen site is an is typical of many sites where rural IDPs have been dispersed to. Many residents of this area are IDPs ‘in hiding’ in the war zones, as well as more settled villages that often act as temporary hosts in the KNU’s Taw Oo (Toungoo) district. Our partners here were the KNU Economic Committee Secretariat and the KNU District Committee.

Myaing Gyi Ngu, located in central Karen state, near the state capital, Hpa-an

This site was set up as part of a repatriation process that started in 1996 (see Lang, 2001). It hosts three IDP camps that were set up in 2016 and transformed into settlement areas in 2022 and now serves as a location for both spontaneous and facilitated refugee and IDP return settlements. The town itself was established in 1994 and has been hosting IDPs and refugees since then, even before formal camps were set up in 2016. Three types of displaced people live in Myaing Gyi Ngu, including long-term IDPs who arrived from 1990s onwards, those who arrived from 2016 onwards and those displaced by the recent violence since the military coup in 2021.

The site is under the control of the Myanmar army’s border guard force (BGF), posing serious protection concerns for the residents. Our partners here were local civil society actors. The Myaing Gyi Ngu context allows insights into the lives of IDPs who have fled from the war zones into an area controlled by pro-junta militias, with a strong influence from the local Buddhist monks.

NMSP ceasefire zone, located in southern Mon state

This overlaps with northern Tanintharyi and southern Karen state. This area has been relatively stable since the 1995 NMSP ceasefire. It features a combination of resettled refugees and IDPs, many of whom have yet to find ‘durable solutions’, and local villagers, as well as NMSP personnel. The Mon site includes people who were repatriated from refugee camps in Thailand in 1996 (UNHCR, 2001), and other more recently arrived IDPs, most of whom are relatively securely settled in areas under NMSP control. Our partners here were the NMSP as well as the Mon Women’s Organisation.

Quantitative methods – baseline and panel surveys

With regard to our quantitative household survey, a total of 169 respondents, representing a proportion rate of 10.21%, participated across 13 selected villages within the NMSP-controlled area’s two resettlement sites, Ye Chaung Phyar and Khalout Khani/Three Pagoda Area. In Taw Oo, 115 respondents from six selected villages in the Htaw Ta Htu and Dohparkoh townships were surveyed, accounting for a proportion rate of 20.32%. These villages were selected by taking account of security conditions and accessibility. In the Myaing Gyi Ngu region, 182 respondents participated, corresponding to a proportion rate of 9.76%. Village selection followed a purposive sampling method. For Taw Oo, a 20% proportion rate was chosen due to ongoing fighting, restricting access to only six villages during that period. The survey took place from January 2023 to early March 2023, conducted by a team of 12 enumerators in three languages: Karen (Pwo and S’gaw), Mon and Burmese.

Three separate teams engaged with various gatekeepers to facilitate the research process. The Taw Oo team secured permission from the KNU Taw Oo district leader, who informed the relevant village head about the research in the target area. The Mon team sought approval from NMSP leaders, while the Myaing Gyi Ngu team obtained permission from the Urban Committee members. Thanks to their good relationships with these authorities or gatekeepers, all three teams managed to conduct the research seamlessly. This was a considerable achievement, as all teams encountered security challenges. In particular, the Taw Oo team re-routed their access to relevant villages to maintain the safety of the researchers.

Qualitative interviews

With regard to the qualitative data, the initial round of qualitative interviews consisted of 51 interviews in the Myaing Gyi Ngu area, 56 interviews in NMSP area and 50 interviews in Taw Oo, conducted between December 2021 and June 2022. The second round of oral history interviews included 24 interviews in Myaing Gyi Ngu, 25 in the NMSP area and 25 in Taw Oo, and took place between April 2023 and June 2023. Additionally, three follow-up interviews were conducted in the Myaing Gyi Ngu region for displacement narratives.

Three focus group discussions (FGDs) were held in the NMSP area, four FGDs in Taw Oo and three FGDs in Myaing Gyi Ngu. Alongside this, we held seven key informant interviews (KIIs) conducted in the NMSP area, eight in Taw Oo and nine in Myaing Gyi Ngu. The FGDs and interviews involved a range of stakeholders, including businesswomen, local authorities, CSOs and EAO members, and took place between June 2022 and August 2022.

Production of documentary films

A filmmaking workshop took place in Mae Sot, a city in western Thailand that shares a border with Myanmar, from 5-10 January 2023. It was facilitated jointly by a professional filmmaker based in the UK, and our Myanmar-based communications officer in person. It was attended by 12 participants, all from Myanmar, some of whom were based in Mae Sot.

During the workshop, three films were successfully produced:

The Bitter Embrace

A film by: Saw Simon; Saw Thet Thet; Saw Ner Doo; Naw Jasmin

This portrays the life of a man in Mae Sot, Thailand who falls into the grip of alcoholism after being displaced by the military dictatorship in Myanmar. As he struggles to find work, his family grapples with the consequences of his addiction and the lasting impacts of displacement.

3:27 mins; Karen and Burmese with English subtitles, 2023.

She faked it till she made it

A film by: Saw Taulk; Nay Nay; Saw K’Paw Htoo; Angela Aung

This film chronicles the journey of Sucee, a transgender individual who, after being displaced from Myanmar to Thailand, establishes an online shop selling teas and medicines. As a trans woman, she finds some acceptance that she did not have at home.

3:23 mins; Karen with English subtitles, 2023.

I had dreams, but

A film by: Eim Pakao; Saw Void; Saw Lin Htet; Eileen May

This film delves into the story of a young person whose dreams were shattered by the military coup, and slowly reborn in displacement.

2:40 mins; Burmese with English subtitles, 2022.

Participants valued the chance to receive professional insights into the art of filmmaking. The diverse backgrounds and experiences of the participants, including the presence of at least one individual from Mae Sot in each group, with the remainder from Myanmar, contributed to an enriching environment. Given that most attendees shared the same ethnicity as the filmmaking subjects, and those from Mae Sot had connections with the subjects of the film, the process of establishing connections was more seamless. The chance to explore personal stories of resilience, transformation and the impact of displacement added depth to the filmmaking process, making it rewarding for all involved.

Key findings from Myanmar

Displacement-affected communities

Myaing Gyi Ngu village is an IDP settlement established in 1994 and has since then been a home to IDPs and returned refugees. This area is under the day-to-day control of ethnic Karen BGF, which operate under the authority of the Myanmar army. These groups have a poor human rights record and on many occasions have launched attacks on civilians as well as rival EAOs. However, in Myaing Gyi Ngu itself communities do not report frequent violence, and the settlement is under the leadership of a group of local monks.

Following the fighting between joint forces of Tatmadaw and BGF and a splinter group of the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army (DKBA) in September 2016, additional temporary shelters were set up. This ‘camp’ area was transformed into a settlement in 2022, and some recently arrived IDPs have been settled in wards of more long-term IDPs. Some individuals who have been displaced since the 1990s consider themselves part of the host communities and as permanent residents in Myaing Gyi Ngu. IDPs originate from Mae Ta’ Waw, Hpapun township, Hlaingbwe township and Hpa-an township, primarily belonging to the Pwo Karen ethnic group. While there are no ethnic tensions observable within Myaing Gyi Ngu itself, it is important to note that Muslim IDPs are not allowed to enter the area.

Regarding religion, almost all IDPs in Myaing Gyi Ngu practise Buddhism. The head monk has expressed concerns about potential religious conflicts and consequently, other religious groups are not permitted to settle in the town. However, there are a small number of Christians residing in Myaing Gyi Ngu. They tend to keep a low profile and live harmoniously with others.

Many residents undertake so-called ‘merit work’ – voluntary labour performed to earn religious merit – at the request of the local monks. This may include some construction work, stone masonry and other maintenance tasks. While some residents view this as forced labour, others regard them it as voluntary merit-making work. The Myaing Gyi Ngu area is strongly influenced by local Karen nationalist monks, who are generally opposed to the KNU and other EAOs struggles. An informal network of CSOs provide a range of services to communities in and around Myaing Gyi Ngu, including training and livelihood support activities. The monks in this setting perform the role of intermediaries between the IDPs and their access to resources. How they do so in the presence of CSOs who are not looked upon favourably by these monks can provide an interesting backdrop; however, there is no obvious tension observed. Their role is also important in the context of mutual aid and support.

Recent arrivals receive food donations from the monks and also parcels of land. A 42-year-old woman talked about the support she had received from received by the monks, and through international NGOs. Although she wanted to, she could not go home because she would be subject to forced conscription or portering: ‘If we go back to our village, we will have to serve in the military.’ A 44-year-old woman talked about moving to MNG to avoid violence in the conflict zones. She feels protected by the monks’ chanting of Buddhist scriptures: ‘This area would be unsafe without the chief monk.’ New IDPs would like to go home and pursue their original occupations, such as animal husbandry and farming. However, they cannot go back because of the conflict in their villages of origin. There are very limited job opportunities and most only do casual labour, including farming and clearing the land for agriculture at the farms of residents of outside villages. Our research found evidence that people displaced during earlier conflicts in the 1990s had settled in this town. Some of them are financially settled and they can rely on themselves now, though this does not necessarily translate into employment opportunities for newly arrived IDPs.

NMSP ceasefire zone (peri-urban, Mon area)

The ethnicities represented in this area include Dawei, Mon and Karen, and the religions present are Buddhism and Christianity. Villagers interact with neighbouring villages that are more established. There are schools and services present inside the ‘new’ villages. In two of the three areas, IDPs do not mix with non-IDPs, but in the area with a high school they mix at school.

Schools and healthcare and some other services are provided by NMSP and Mon CSOs. The NMSP has sought to provide a secure environment in its demarcated ceasefire zones, protecting local Mon communities, including long-term resettled refugees or IDPs, from state incursions and military violence. As a 59-year-old villager said, ‘We are safe here [because the NMSP has a] security guard.’ A 37-year-old woman agreed: ‘It is peaceful here under NMSP control.’ However, particularly after the coup, travel beyond NMSP areas[1] is difficult and dangerous.

The NMSP has provided land to most resettled IDPs and refugees. With limited international funding, the party’s Mon National Education Committee delivers a highly successful education service to civilians in its areas of control. In this context, the NMSP works in partnership with Mon CSOs to provide basic support and community development.

Taw Oo (Toungoo) district

Taw Oo district is under KNU administration, but the human security situation since the coup has been characterised by widespread violence, perpetrated by the SAC junta. This violence is to some extent the consequence of the actions of the anti-resistance group known as People’s Defence Forces (PDFs). There have been incidents in which PDFs have initiated attacks on Myanmar army troops in close proximity to schools, thereby putting both students and teachers in danger. Reports have also emerged regarding threats made by PDFs against Karen CSO leaders. The KNU is widely perceived as protecting villagers from the Myanmar army. A 69-year-old farmer told researchers that ‘we have protection from our Karen army… If they are not near to us, we will get abused in different ways’ (by the Myanmar army). As in NMSP areas, the KNU provides basic health and education services, which are trusted by the community and adapted to local needs. A middle-aged farming couple explained that ‘we live in the KNU administration area… we trust the KNU will protect us.’

While the majority of people in Taw Oo have experience of displacement, some have been there longer than others. Among them, the longest-displaced arrived up to 30 years ago, since the four-cut campaign by the Myanmar Army in late 1950s, which involved systematically cutting supplies, recruitment and communication strands. The communities mix with each other. Several IDPs have undergone multiple displacements. They initially sought refuge at the Ei Thu Hta camp in Mutraw District (District 5) of KNU during the 2016 conflict. Subsequently, due to the cessation of relief aid from international donors at the camp in October 2017, some of them returned to Taw Oo while others sought refuge in different locations.If there is a clash in the village, they flee to the town or jungle, or if there is an armed conflict in town, they go to the village. Mostly, they flee for a few days and when the situation gets better they go to their original village to continue their livelihood activities, such as farming at their own farms.

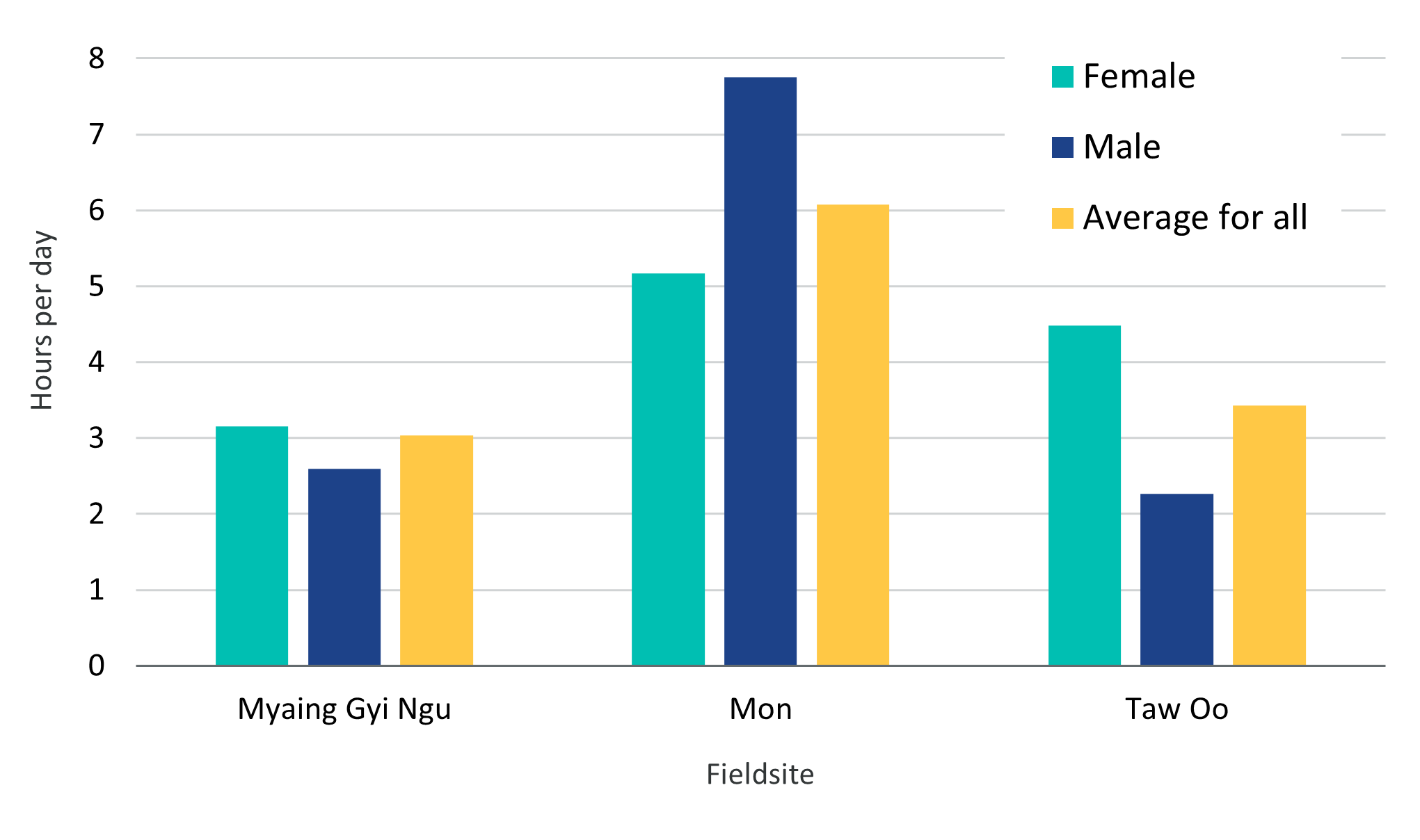

Feminist economies and mutual aid

Notably, gendered divisions of labour in displacement vary quite significantly across the three sites, with the highest proportion of male household labour being evident in the Mon area. How exactly they matter is therefore an issue for further investigation. In Myaing Gyi Ngu, as seen in Figure 2 below, women allocate an average of 3.15 hours per day to caregiving responsibilities, which is only 0.56 hours more than their male counterparts, on average. In contrast, women in Taw Oo spend approximately 4.48 hours daily on these duties, which is twice the amount contributed by male respondents. The quantitative data for Myaing Gyi Ngu and Taw Oo regions is complemented by our in-depth interviews, where we found that many female IDPs in Myaing Gyi Ngu assume caregiving responsibilities, such as looking after sick children and elderly family members, alongside their household chores.

Gendered division of household labour

In addition to this unpaid work, some women engage in income-generating activities from their homes. This is especially well documented in Myaing Gyi Ngu. It might include activity such as operating small grocery stores or workshops producing bean curds, such as that undertaken by a 61-year old Burman woman, as well as weaving traditional dresses to supplement their family earnings, as explained by a young woman who was born and raised in Myaing Gyi Ngu. Despite the challenges of her family’s displacement, she pursued her education and is currently a final-year university student. She runs a small online business selling Karen traditional clothes, which she sources from local weavers in the camp.

Some women even establish small mohinga (traditional Burmese food) restaurants or restaurants that sell vegetarian food. Some of these businesses, such as weaving traditional dresses, are solely done by women. In the Myaing Gyi Ngu area, many male IDPs engage in work outside the house, including working as labourers in other people’s gardens and running boats. The care provided by female IDPs enables their husbands to work outside the home, thus contributing to the economy. One research team pointed out that women’s care work tends to limit their ability to earn an income outside the house, such as making traditional dresses. In the Myaing Gyi Ngu area, in a few households (MGN A 03), women and men equally share the responsibility of household chores and work both inside and outside the house. The entrepreneurial spirit among women is notable in the Linn-Lon-Myaing area of Myaing Gyi Ngu. These women not only manage businesses but also oversee human resources and establish networks to expand their market presence, such as a 32-year-old Karen woman from Kayin State we interviewed, who has lived in Myaing Gyi Ngu since her family fled conflict and relocated there in 1996. The daughter of a former KNU soldier, she grew up in the camp and now runs a small family business producing and selling mohinga alongside her husband. A high school graduate and mother of two, she is an active contributor to her community, employing local youth and participating in social activities. A 48-year-old woman entrepreneur who runs a clothing shop and solely supports her entire family noted that, in comparison to men, women tend to work longer hours and take on more leadership roles at work.

In the Taw Oo area, as in Myaing Gyi Ngu, women are often the primary carers and take on household chores. Men typically work outside the home, often returning in the evening after working on farms or other income-generating activities. This division of labour often results in unpaid household work performed by women, which can contribute to gender inequalities and reinforce gender roles. Women’s work in the home, which is essential for the well-being and functioning of the family, is typically undervalued and not monetarily compensated. As one 39-year-old male respondent argued:

Most of the housework (cooking, washing clothes, looking after children) is done by women because these are considered women’s responsibilities and they are seen as experts in these tasks. Women are also thought to be too weak to do the kind of work men do.

However, there are signs that the dynamics are shifting over time, and in some households, both men and women work together on farms, with the use of machines making work easier. Although participants mention equal treatment in terms of wages, if their working conditions were different they were paid differently. For example, if a man picked rice and a woman planted it, the wage would usually not be the same.

Interestingly, in the Mon area (NMSP ceasefire zone), men tend to assume a greater share of caregiving responsibilities compared to women respondents. Women in Mon devote 5.17 hours per day, while men take on an average of 7.75 hours per day in caregiving tasks. However, in contrast to the quantitative data, in the Mon area the interview team found that caring is primarily carried out by women, with many men rarely getting involved. However, there were few reports of gender discrimination in terms of work, either inside or outside the house. It was felt that men and women work equally and contribute in the same way, even though people observed that women take on more responsibilities in terms of childcare and household tasks, while men engage in outside work more frequently. Some argue that there is an equal division of labour between female and male IDPs, with each taking different roles to complement each other. For instance, while men climb trees and pick betel nuts, women dry the nuts that are harvested by men. However, there are certain types of work that are typically considered women’s work, such as removing husks from betel nuts, as reported by some respondents.

Cultural and societal standards influence the distribution of work, with physically demanding labour and less labour-intensive tasks assigned differently. For example, activities like upland gardening, tree climbing and tree cutting are typically assigned to men. However, when necessary, for instance, when there are no men in the household or when more labour is needed, or when there is an economic need, women are also expected to participate in these tasks. In terms of wages, men generally earn more than women, even though some women have the same working abilities, work very hard and handle heavy tasks just like men. The disparity in wages exists because employers perceive men as being capable of doing more physical labour, while women are often undervalued and receive lower wages as a result.

Remittance support

The political and security crisis, and deteriorating economic conditions in the country, including low wages and rising commodity prices, make it challenging for people to sustain their livelihoods within their local communities. As a result, many individuals choose to migrate and work in other countries where they can earn higher incomes and remit money back to their families.

According to the quantitative survey, in Myaing Gyi Ngu, 16.11% (n=29) of respondents receive remittances from household members living both within Myanmar and abroad. In Mon, 23.66% (n=40) receive such remittances, while in Taw Oo, the percentage is lower at 3.5% (n=4). A recent socio-economic household survey carried out by the Karen Economic Committee reported that over 21% of households in Karen areas of south-east Myanmar receive remittances from abroad (Karen Economic Committee, 2023). This financial support from family members working abroad plays a crucial role in assisting their families in meeting their basic needs, including purchasing food and covering medical expenses. However, the process of migration itself can be costly, with individuals needing to pay agent fees and often relying on loans to cover the expenses associated with migrating.

As the survey data above shows, remittance income is very uneven between the three sites. It is worth mentioning that support for IDPs in the Taw Oo area comes from the overseas Karen community, some of which is additionally faith-based. Those who were displaced due to the civil war and subsequently resettled in a third country, such as the United States, also provide donations to the village as a means of giving back. The diaspora community provides financial support to the church, particularly on special occasions like Christmas and Karen New Year celebrations. Additionally, individuals living abroad support elderly people in the village by providing them with small amounts of money, reciprocating the support and help they received from them during their own childhood or youth. Furthermore, these individuals contribute to the village’s development, such as the construction of a church hall. One 43-year-old woman we interviewed said:

As we are Karen people and Christians, helping others is simply part of our attitude and habit.

This suggests that the act of helping others is deeply rooted in their identity and values. A few IDPs mentioned their belief that by helping others, blessings will be received in return. Few IDPs help others because they expect help in return. Some IDPs help because of their empathy, as they understand the challenges and circumstances faced by displaced individuals, as illustrated by this respondent:

I helped them because I was sympathetic to them. So, if there is an emergency, we can call our neighbours to help us.

Mutual aid

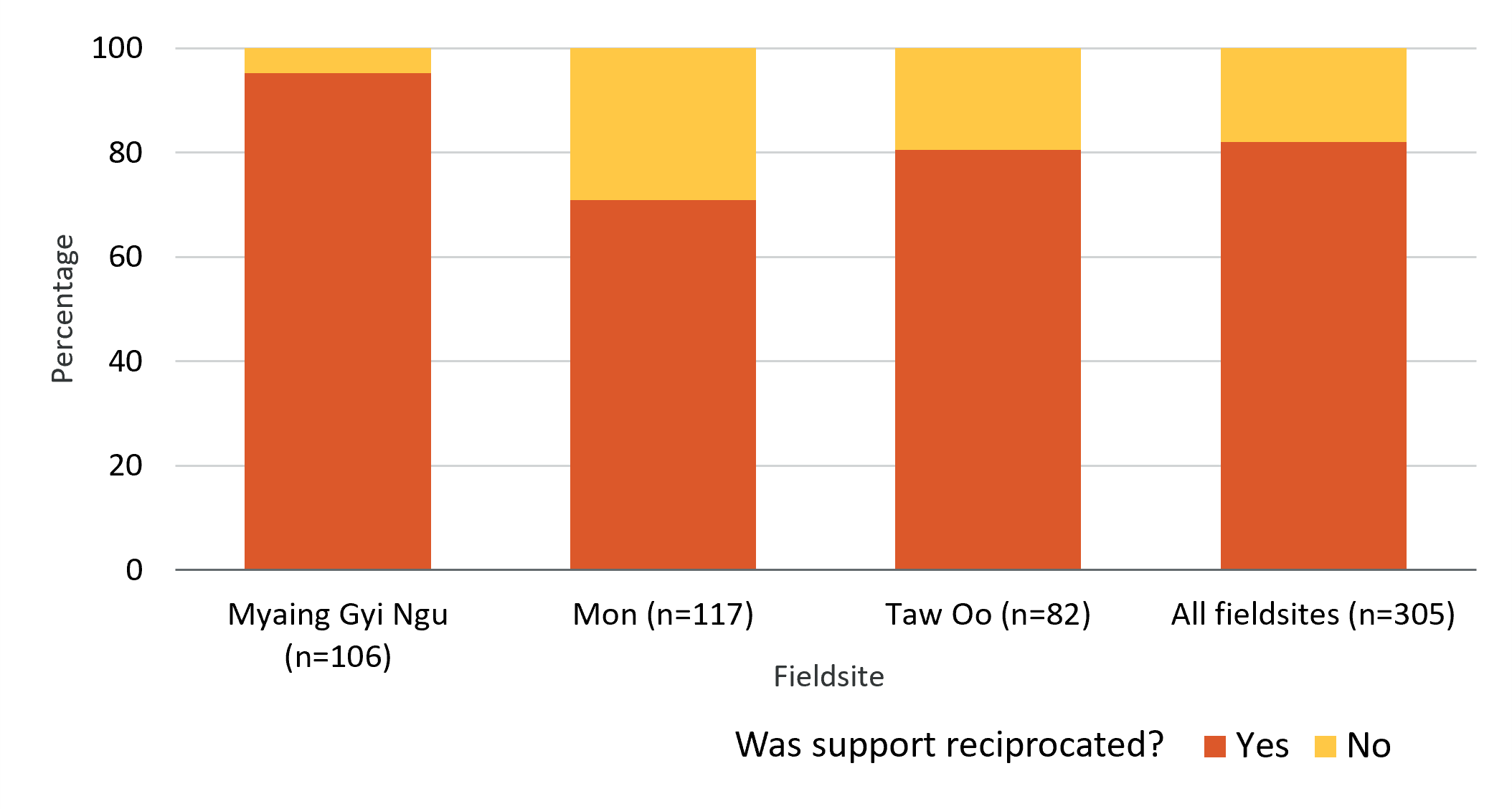

There is strong evidence of mutual aid being extended between IDPs in all locations. Based on the quantitative data, it is reported that 95.3% of households in Myaing Gyi Ngu mentioned that support is reciprocated, followed by 80.5% in Taw Oo and 70.9% in the Mon area. Please note that this question was asked only to individuals who had previously provided support to their neighbours.

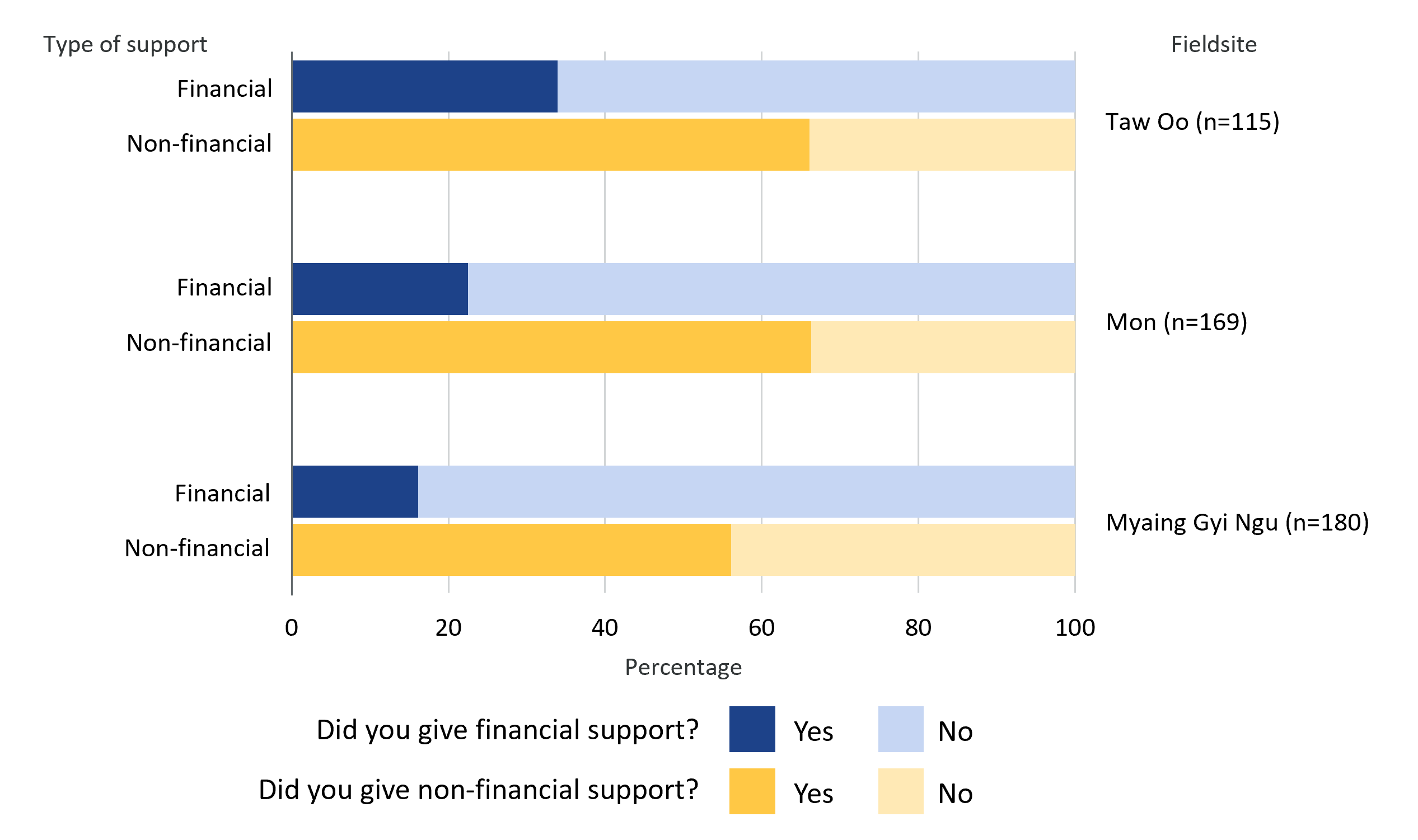

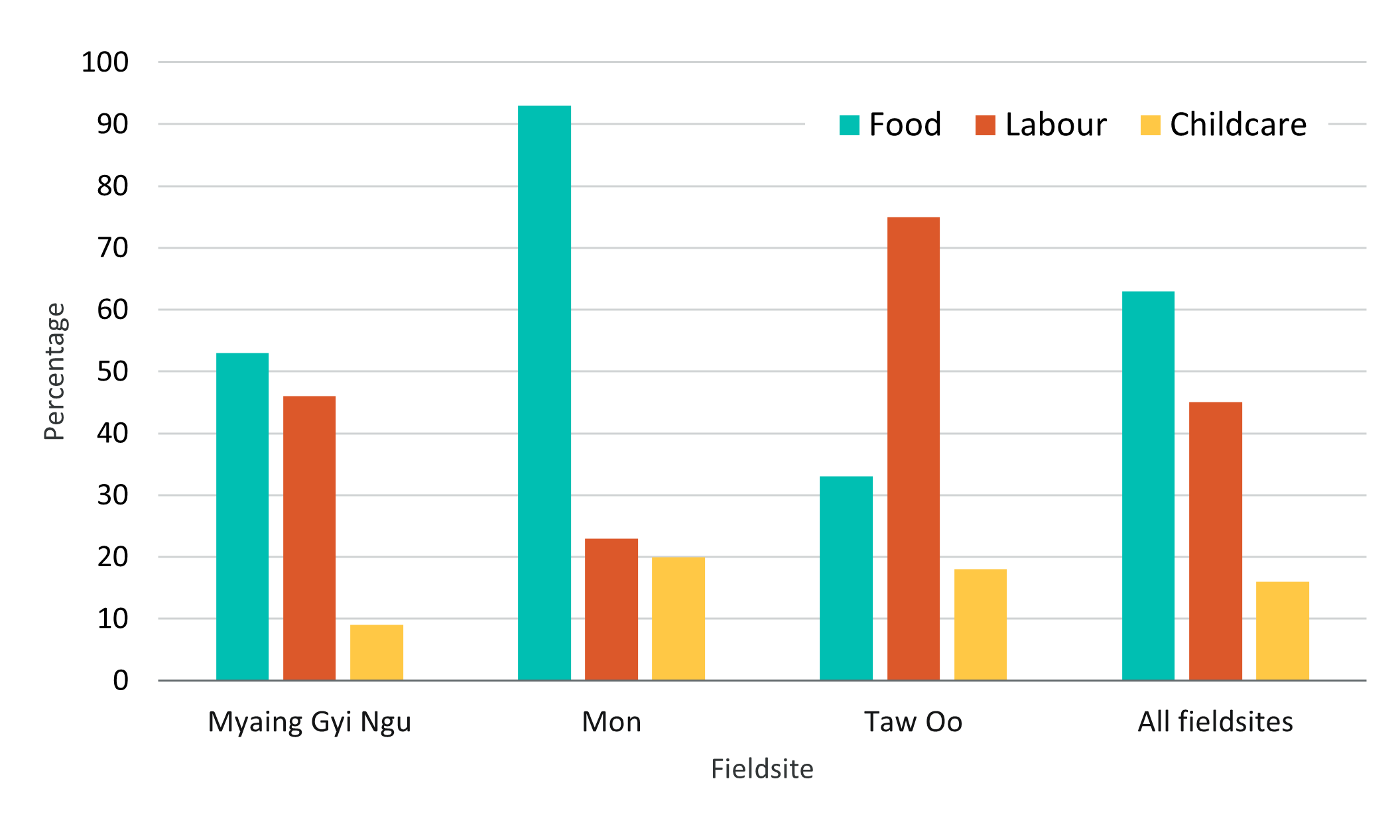

This support typically takes the form of non-financial assistance, including food, labour and childcare, as indicated in the figures below.

In line with our quantitative data findings, in the Myaing Gyi Ngu area long-term IDPs, particularly those who arrived during the 1990s and 2000s, provide both financial and non-financial support to other displaced people, as many of them are in a better economic situation than recently arrived IDPs. Those that arrived after 2016 are not very well-settled yet compared to longer-term IDPs who arrived in 1990s and 2000s. They were recently relocated to new areas within Myaing Gyi Ngu town after the camp area was transformed into wards. It is noted that support offered can take various forms, financial as well as non-financial. As one respondent, who has lived in Myaing Gyi Ngu (MGN) since 2003, stated:

At the time of becoming financially independent, I used to help my relatives and neighbours with cash, food and other support. I provided cash if they asked me to.

This includes sharing food and other essential items, as well as sharing information, thus creating a sense of connectedness and solidarity.

Notably, recently arrived IDPs primarily assist each other through non-financial means, as a 51-year old woman from the Myaing Gyi Ngu settlement explained:

To be honest, I don’t have much extra to share with others myself. The most I can do to help them is allow them to buy goods first and pay me back later when they have the money individually. This is the only way I can assist others at the moment because I arrived here only six months ago. Occasionally, my neighbours help me watch the shop for a short time when I need to shower or run errands. The area where I live mostly consists of newly arrived IDPs, and we primarily provide physical support for each other. Unfortunately, we are unable to support each other financially.

Importantly, mutual aid and support exist among both the residents and IDPs, as one 39-year old woman, also from the Myaing Gyi Ngu area, noted:

Since my son started attending school here in Myaing Gyi Ngu, he has been receiving a uniform, notebooks, pens, pencils, and other necessary school supplies every year. On occasion, the school administrator and their team visit to collect school supplies, emphasising the importance of supporting newly arrived IDPs. In such cases, I contribute by providing monetary assistance, as well as notebooks, rulers, pens, pencils and other supplies. My neighbours are always willing to lend a helping hand whenever it is needed. For instance, if a family member falls ill and I need to take them to the clinic, my neighbours assist me by looking after my shop for a short period of time. Likewise, if a neighbour requires similar assistance, my husband and I are ready to help them… At times, my husband extends his help to others in the neighbourhood, whether it involves fixing houses, repairing roofs or digging the ground to access water below the surface. In the area where I currently reside, there is no discrimination… We live together as a close-knit community, as we all come from different places and do not have immediate family here… In Myaing Gyi Ngu, individuals from diverse backgrounds coexist harmoniously, treating each other like family and offering mutual support.

Similarly, in the NMSP area, there is a powerful sense of community and villagers support each other. This is the common cultural practice in these villages. Community members mostly support each other through non-financial means. This includes sharing resources (including food), supporting neighbours when they are sick, helping with chores and accompanying others to hospitals or clinics. In particular, women will go to the house of vulnerable people, help with cooking, accompanying family to hospital, sometimes accompanying them at night with their family. Sharing of resources includes sharing food, vegetables, meat and fish, as well as borrowing and lending items when needed. The sharing of resources helps to address food insecurity and ensures that everyone’s basic needs are met.

One of the women in the Mon area, aged 52, illustrated their situation as follows:

This is what my family typically experiences: food insecurity. When I didn’t have anything to eat, I would buy food on credit, from the shop; pick vegetables from the garden, and occasionally rely on the generosity of our relatives who would send us food when they knew we were struggling. Borrowing food on credit from the shop has become a frequent occurrence for me. I have received support from my relatives, and in return, I share vegetables with relatives who live nearby and also with our neighbours.

Another participant from the Mon area, a 47-year old man, further explained:

We live in this village and everyone’s like brothers and sisters. If we don’t have food, we rely on each other to borrow and eat. In times of need, we ask for help and borrow from each other. We just buy what we need. I wouldn’t say everything is perfect in this village, but we take care of one another, and I know everyone here.

In the NMSP area, many respondents expressed that they did not have any expectations for assistance and showed sympathy towards the difficulties faced by others. Some respondents also mentioned that their actions align with their religious beliefs, such as the concept of karma, and they feel compelled to help those in need as part of doing good deeds, as a 34-year old man from the Mon area pointed out:

If there are people who don’t have anyone else to rely on, I help them more. Wouldn’t we receive more good deeds for our next lives if we help others? Some people believe that what you do to others will come back to you, so they help them.

In many areas, local communities have established various groups such as social welfare, youth and women’s groups at the village level. These groups engage in micro-saving initiatives, pooling funds to facilitate low-interest borrowing opportunities for their members and other villagers.

One of our respondents was a 59-year-old Mon man who founded a micro-saving group in the NMSP-controlled area. He lives in Johaproud village with his wife and five children. A former member of the NMSP, he spent many years moving between duty stations before settling in the village in 1997 to focus on his family and livelihood. He told us that:

We charge a 3% interest rate on the money, and the majority of people who save money with us do not borrow. So, we can share the benefits with the wider community, even though they are not members of our group since they do not have funds to contribute.

In Taw Oo, community support, such as help from direct neighbours, neighbouring villages, relatives and host communities, plays an essential role in the resilience of displacement-affected communities. A supportive network that is willing to help IDPs can be very beneficial during times of hardship or when facing challenging situations. This reliance on mutual aid has helped communities survive for decades. Village leaders play a role in managing support initiatives by collecting donations from villagers and distributing them to those in need. The collective effort of the community ensures that assistance is provided to those facing hardships.

Some villagers remain in their old settlements, while many others have been forced to flee in the face of air and land attacks. Relatively secure (‘host’) communities do what they can to receive fleeing civilians, who generally belong to the same ethno-linguistic and (mostly) Christian networks. In the Taw Oo district, the majority of IDPs are of Karen ethnicity and practise Christianity, with some following animist beliefs. However, there are also minority ethnic groups such as Kayah, Pa-oh, Burmese and Shan Buddhists residing in the district. Despite the diversity of ethnicity and religion, there was no tension observed in Taw Oo District, and IDPs actively support one another.

The support provided is primarily in the form of non-financial assistance, such as repairing roofs, building houses, cultivating crops and lending motorbikes for transportation (of people, food or agricultural supplies), and giving and lending food supplies (usually rice). Financial support is limited, but when possible, villagers collect and contribute money for the welfare of the poor, the sick and the elderly. For example, a 49-year old farmer in the Taw Oo area explained that:

We help each other by repairing the roof, growing paddy, and so on. We could not afford to support each other with money. If we need help, we can ask any time from them.

Nevertheless, displaced people recognise the limits of mutual aid. When talking with two farmers from the Taw Oo area, 57 and 41 years old respectively, the former said:

As we all are in the same situation as displaced persons; we cannot help each other much but we help each other as much as we can such as sharing some food or something like this.

This mutual support extends beyond family members and includes other members of the community as well. The host villagers are willing to extend their support to displacement communities by providing them with food and shelter when they have nowhere else to go. A female farmer aged 42 from the Taw Oo area explained their own situation:

We need to find the house to live here, there, anywhere randomly [they requested host house owners’ permission to stay, until they found someone who could help]. At that time, Per Daw Day villagers helped us to carry our belongings like rice packs to the host village.

Another participant from the Taw Oo area, a 42-year old Christian man, explained:

As they [host villagers] are Christians, they sympathise with us and accept us. They mentioned that if they did not accept us, we would have nowhere to go. We ended up living with them for 12 years, but we did not build a proper house. Instead, we built a small tent.

It is also seen that villagers who have experienced displacement in the past come together to provide support rice and essential supplies to newly displaced people. This aid is provided despite the villagers themselves not having an abundance of resources, but because of their empathy for others.

Further, a 32-year old female teacher at a Christian missionary school in the Taw Oo area highlighted how IDPs become supporters of others too:

We help other people too. After we were displaced to Aye Kyaw villages, we can come back to live in our village after the situation is better. So, we can work in our village and our livelihood situation becomes better compared to the displaced period. So, last year when the people from the Karenni state fled from the war and were displaced to the Aye Kyaw village, our family helped them by giving five packs of rice for them, because we know the situation of the displaced other villages and have sympathy.

Another example of such aid is given by a CSO leader and Church youth pastor who explained:

In the past few days, I visited Taw Oo [Toungoo] town and organised and gathered 20 bags of rice to be sent to the current IDPs who have fled from another district. Several villages collected vegetables from their farms and distributed them to the displaced people. Furthermore, some individuals sent money to provide support for the IDPs to purchase food for their cooking requirements.

The church also plays a role in providing support, collecting food and offering assistance, although it may not always be sufficient. In some cases, there are charity ambulances available to transport villagers to hospitals when needed. As the findings in this section have shown, informal support amongst residents is in many ways the backbone of short-term survival strategies, with longer-displaced IDPs often assisting more recent arrivals. However, it is unclear what kind of practices might transform into long-term, sustainable livelihood mechanisms.

The humanitarian anchor – localisation and sustainability of aid

In the Myaing Gyi Ngu area, both UN agencies and INGOs have played a vital role in supporting the population in Myaing Gyi Ngu in comparison with local or national NGOs and CSOs. Moreover, the residents in Myaing Gyi Ngu perceive UN agencies and INGOs as trustworthy organisations that have a substantial budget to secure and support their basic needs. This includes initiatives such as providing access to electricity, installing infrastructure like solar panels, constructing school buildings and water storage tanks, and facilitating the development of sanitary facilities. For example, UN Agencies such as WFP and UNHCR provide rations, oil and rice, and other dried food.

During the challenging context in post-coup Myanmar, the local authorities, including influential groups such as the Myanmar army-controlled Karen BGF, Buddhist monks and urban committees, only permitted registration and recognition of organisations that meet specific criteria. As a result, it became increasingly difficult for local organisations without valid registration to continue providing support in the Myaing Gyi Ngu area. Community-based organisations or local NGOs whose licences have expired have to work in a low-profile manner, as the BGF reports all activities to the State Administration Council (SAC) junta. Consequently, the operational space for local NGOs and CSOs has shrunk under the rule of the SAC in Myaing Gyi Ngu. The relationship between local authorities and CSO members has become fragile, and the working environment for organisation staff is characterised by high-risk conditions and an overall lack of security in communities.

Moreover, due to registration problems, some NGOs and CSOs have faced funding cuts from donors such as UN agencies, as donors only provide funding to those with valid registrations. Having no valid registration impacts donor trust, and due to the funding cuts, CSOs and local NGOs cannot adequately and promptly assist the IDPs. This situation has left CSO and local NGO members feeling frustrated, leading them to advocate for more flexible funding criteria during the UN coordination meetings and a more adaptable banking system. However, these efforts have not yet succeeded.

Nevertheless, the local network and local organisations exhibit considerable resilience. Networks such as the KNU-aligned Committee for Internally Displaced Karen People (CIDKP) continue to provide humanitarian support. Occasionally, donors bypass community committees and approach BGF leaders and the Sayadaw [the chief monk, or Abbott] directly to implement activities. Unfortunately, there have been reports of corruption involving BGF members and urban committee officials mishandling the donated resources. Not all aid donations reached their intended beneficiaries, leading to a lack of trust in the system and causing some organisations to hesitate in providing aid through these channels.

Emergency humanitarian support cannot be a sustainable solution in the long term. For example, much depends on the charisma and attitude of leading monks, who play a key role in managing the IDP settlement area. To address this, vocational training programmes have been implemented, offering training in sewing, motorcycle repair and house wiring to IDPs. Some of this, such as sewing training, was provided at the Cultural School by the Ministry of Border Affairs. The Local Resource Centre ran vocational training in 2020-21, providing all trainees with sewing machines. However, since these programmes were provided on a short-term basis, the urban committee has encouraged the implementation of long-term training programmes to ensure sustainability.

UN Women supported the Myaing Gyi Ngu women’s group by providing them with a sub-contract. The focus of this project was the production of traditional Karen dresses, which were sold to guests in Myaing Gyi Ngu and through their network in other parts of Myanmar, such as Yangon. Even though the project has officially ended, the women’s group continues to operate this business, contributing to their economic sustainability. The Myaing Gyi Ngu Women’s Committee, consisting of five to seven members, including both elderly and young IDP women, oversees the operations and collaborates with around 20 to 30 women within their network who were tasked with producing the dresses. The Women’s Committee is responsible for management, procurement of raw materials and trading activities. It sells the clothes in Myaing Gyi Ngu and sends them to customers in Yangon.

Some long-term IDPs have successfully started their own businesses. They have established thriving enterprises that provide employment opportunities and contribute to the local economy. Two of our respondents from the Myaing Gyi Ngu settlement, for example, run small businesses. One was able to offer jobs to three local boys at her mohinga shop to help manage their small business and sell the products to the villages around the area, while another, a 37-year old woman who runs her own business preparing betel nut packages, explained that her business employed at least 15 employees, and at times more than 20.

However, in the absence of formal job opportunities and very limited informal work, the community actively participates in volunteer work for monks. One IDP, a 40-year old ethnic Karen woman, noted that:

Finding employment has become increasingly challenging as jobs have become scarce. Even educated individuals are facing difficulties in securing employment.

It is worth noting that the monastic community at the Myaing Gyi Ngu site plays a crucial role as mediators, as well as managing the overall IDP situation. Exploring sustainable business practices and fostering entrepreneurship among IDPs is crucial to creating a sustainable and self-reliant environment for its residents. Possessing, or having access to larger landholdings will allow IDPs to engage in agriculture, thus enhancing sustainability. While some IDPs currently practise home gardening on the land provided by the monks, the local team observed that the fertility level and soil condition are poor. Additionally, there is a shortage of water during summer, which can be attributed to climate change and the absence of wells in certain wards. Access to reliable water sources and electricity would enhance their ability to sustain their businesses and improve their overall quality of life. Efforts to address these infrastructure needs will support the long-term sustainability of the community.

Moreover, the monks take an active role in supporting the IDPs in the area by providing land and food assistance. Additionally, the monks have focused on infrastructure improvement, specifically roads and bridges, with the dual objective of fulfilling their religious vision and promoting economic development in the region. Many recent IDPs provide unpaid labour for the monks in construction and various other tasks, in the context of ‘merit work’ required by the monastic community. Given the limited job opportunities in the region, this volunteer work serves as a means for IDPs to receive a monthly provision of a bag of rice and some food to sustain themselves.

In the Taw Oo area, outside support in the past few years was limited or non-existent. However, the situation has improved, and some organisations are now involved in providing assistance to the displaced villagers. However, there are still challenges, and the support received is not always sufficient to meet all the needs of the displaced population. The KNU, CSOs and local NGOs have long been involved in supporting and promoting development in the region. Many of their projects have received funding from international sources. Due to the limited presence of secular CSOs in the past, social development activities were primarily facilitated by the Christian church departments.

As a result, faith-based support is especially important in the Taw Oo area. The church network has provided emergency support including cash, and support for microfinance through women and youth groups. The church network coordinates with Hto Lwe Wah school, under the KNU education department, to distribute cash. Furthermore, one church network in Toungoo city assisted over 2,000 IDPs from June to September 2022, providing shelter and other emergency supplies. In addition, some women and youth groups such as Thandaung Thu women’s organisation and YWCA work together with churches and have been providing various types of support including vocational training to IDPs. However, after the coup, they were not able to implement all activities in their target areas since some targeted beneficiaries had fled the villages following conflict. In addition, the Free Burma Rangers are active in the area too.

The Rangers are a multi-ethnic humanitarian service group working to bring help to people in the conflict zones of Burma, including Taw Oo district. Working together with local ethnic pro-democracy groups, FBR trains, supplies and coordinates highly mobile multipurpose relief teams. After training, these teams provide critical emergency medical care, shelter, food, clothing and human rights documentation in their home regions. Following the coup, FBR stepped up its work across many parts of the country, providing immediate, particularly medical, relief, local development inputs and psycho-social support, community healthcare, as well as documenting abuses and undertaking extraordinary advocacy.

Despite limited resources, amid great insecurity, the KNU and partner CSOs provide food, emergency relief for IDPs, health and education services to civilians, access to justice, other services and government administration. Ultimately, however, the heart of self-protection consists of communities helping themselves and each other, sharing food, information and love. The KNU has provided financial assistance to the villagers on several occasions, including food support to recent IDPs (NK 11). While the Karen Office of Relief and Development (KORD) focuses on supporting water and sanitation initiatives, ensuring access to clean water and proper sanitation facilities, the CIDKP has provided essential humanitarian aid to those in need, offering assistance during times of crisis and emergency situations.

As one respondent, a 60-year old farmer from the Taw Oo area, emphasised:

Fewer people are interested anymore in education services by the SAC because citizens are excessively worried. There is a constant fear of bombings occurring at any time and anywhere by those opposing the military. Consequently, many students have dropped out of school and now attend the Hto Lwe Wah School, which is under the authority of the KNU.

Moreover, the KNU has taken significant steps towards recognising customary land tenure by providing ‘Kaw’ land certificates and drafting a land policy that acknowledges the sustainable indigenous systems, unlike the land policy of the Myanmar government or junta.

In the NMSP-controlled area, NMSP and Mon CSOs address challenges with projects funded by international donors, the Mon diaspora and migrant workers’ remittances. NMSP established connections with donors following a 1995 ceasefire agreement. The Thai Burma Border Consortium (now the Border Consortium) provided initial humanitarian aid, including medicines, to IDP resettlement areas. The focus shifted from humanitarian to development support around 2004 to enhance IDP livelihoods, also driven by a shift in donor priorities. TBC transitioned to sustainable development, collaborating with local CSOs and NGOs for activities on the ground. NMSP-affiliated local NGOs, like the Rahmonya Peace Foundation, contribute to post-ceasefire projects and support. However, NMSP does not allow INGOs to work directly in the area. It is required for INGOs to collaborate with NMSP’s relevant departments to implement their activities, such as education, healthcare and humanitarian relief aid. CSOs can work in the area after obtaining approval from the relevant NMSP department for project implementation. Effective business management and new sustainable livelihood options, such as fruit preservation, are identified needs. Various training programmes were provided, including sewing, agricultural techniques, land rights, gender awareness and vocational skills. Challenges include a lack of market access for products, emphasising the need for diverse training to create sustainable job opportunities.

Conclusion

Our three research sites are very differently situated in relation to what works to reduce precariousness in displacement. While some of the evidence emerges from all three sites, other support practices matter in some places more than others. Overall, we conclude the following.

The role of intermediaries is clearly central to all three displacement sites, the settlement, the peri-urban area and the rural dispersal area. In the settlement, Myaing Gyi Ngu, a group of local ethno-nationalist monks were central to setting up the site in the first place and they continue to manage it. International humanitarian assistance was facilitated and distributed by them, as well as overseeing the ensuing camp enlargement. Notably, while these intermediaries have enabled many of the residents to have a stable life, they also require the performance of ‘voluntary labour’ or merit work by IDPs, the conditions of which they determine. The relationship between the monks and the IDPs arguably bears the characteristics of a patron-client relationship.

With regard to displacement economies, the most striking finding is perhaps the emergence of women-led entrepreneurship, especially evident in the Myaing Gyi Ngu site. While gendered labour divisions remain at all sites, divisions are shifting and vary in practice. While women’s paid work is often curtailed by restricted mobility, activities such as food preparation and sewing, including marketing their wares outside the area, is a worthwhile avenue of support.

The significance of mutual support is evident across all three areas. However, the sources of this is variable. Many respondents emphasise that the experience of being an IDP makes them disposed to support others in the same situation – although this is not a necessary or sufficient condition to do so. While in Myaing Gyi Ngu, different generations of IDPs create support networks for new arrivals, in Taw Oo support is offered by residential families. There, a close cohesion of faith-based networks, in particular the Christian church, takes a leading role in sourcing and distributing emergency supplies, as well as mid-term support, to IDPs in the area. Both in Taw Oo and in the Mon region, ethnic-based actors, in particular the KNU and NMSP, provide mid- and long-term security and welfare. There are also a number of active civil society organisations on both sites, which take on similar responsibilities to ethnic actors, although the relations between the two are not necessarily without tension.

In sum, our overarching insights highlight the wealth, breadth and variably sourced support networks that exist independently of outside or international organisations and interventions. A key message is therefore that flexibly supporting these networks promises to be the most equitable and efficient way of sustaining and improving displacement economies.

References

Karen Economic Committee. (2023). Kawthoolei Socio-Economic Household Survey, Key Indicator Report 01. https://knuhq.org/admin/resources/publications/pdf/KSEHS_13Oct2023.pdf

KNU, KNPP, CNF and NUG Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs. An Overview and Needs Assessment Myanmar’s Humanitarian Crisis, Period: February 1, 2021 following the Military Coup until July 2022 (9-8-22).

Karen Peace Support Network (KPSN). (2023). A shifting power balance: Junta control shrinks in southeast Burma. (September 26). https://www.karenpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Shifting-Power-Balance-Eng-Sept-2023.pdf

Lang, H. (2001). The repatriation predicament of Burmese refugees in Thailand: a preliminary analysis. Working Paper No. 46. UNHCR. https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/4ff5661a2.pdf

UNHCR. (2021). The displaced and stateless of Myanmar in the Asia-Pacific region. https://reporting.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/The%20Displaced%20and%20Stateless%20of%20Myanmar%20in%20the%20Asia-Pacific%20Region%20-%20January%202021.pdf

UNHCR. (2024). Myanmar UNHCR displacement overview 01 Jan 2024. Operational Data Portal. https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/105901

- There are several varying in size, the largest approximately 50km x 20km. ↵

Voluntary labour performed to earn religious merit in Myanmar.

Traditional Burmese food.