4 Ethiopia

Fekadu Adugna Tufa; Adamnesh Bogale; Asmelash Haile; Priya Deshingkar; and Yasmin Fedda

Early hopes of finding durable solutions to the ever-rising levels of global displacement through resettlement, local integration or voluntary return have proved to be elusive because of complex geopolitical factors. On paper, many countries have demonstrated their willingness to provide assistance to refugees, but the reality is that very few are actually resettled in third countries or integrated in host countries. Returning is not a realistic option for many because of ongoing political conflict and continued persecution based on their religion and ethnicity. The result is that millions of refugees have been stuck for years, even decades, in refugee camps with no immediate prospect of leaving and building a normal life. The concept of protracted displacement was articulated by UNHCR to describe this deepening crisis where refugees find themselves in limbo.

Both UNHCR and governments have focused on the conventional approach of humanitarian assistance, which imagines refugees as passive recipients of aid without recognising their skills, agency and networks of care. The Protracted Displacement Economies (PDE) project was undertaken to shed light on these aspects of refugees’ lives and the multiple and unseen ways in which they support each other in often harrowing circumstances. The project also departs from earlier scholarship by taking a ‘whole of society’ approach, which examines the interactions between the hosts and refugees and how the protracted displacement economy works as a whole. All five countries involved in this project are facing long situations of protractedness.

The research on which this chapter is based used a mixed-methods approach including both quantitative surveys and a range of qualitative research methods to get a broad and deep picture refugees’ situations in the five focus countries. Locally trained teams also produced films to provide visual snapshots of displacement-affected communities’ lives. This chapter discusses the context, approach and key findings of the Ethiopia research.

Protracted displacement and the displacement-affected community

Conflict, climate change and displacement have been part of the history of Somali society in the Horn of Africa for over 60 years. Pastoral mobility established Somali clans and families in the territories that extend from Djibouti in the north-east to north Kenya in the south and that criss-cross the present national borders. Somali nomadic pastoralists roamed countries of the Horn (Ethiopia, Djibouti, Kenya and Somalia). Regardless of their political difference, the Somali in all the four countries have ‘operated as a single economic and cultural space’ (Little 2003 in Carver et al., 2020: 11).

The PDE project uses the concept of ‘displacement-affected communities’ instead of the conventional ‘refugee-host’ dichotomy. The complexities of cross-border displacement and return in the Somali region of Ethiopia make this concept especially appropriate in this chapter. By setting the context of displacement among the Somali population, in this section we discuss who the displacement-affected communities are and why the concept is crucial. The displacement-affected communities constitute refugees, returnees, internally displaced people (IDPs), the host (with multiple experiences) and the diaspora. Most of the diaspora spent time in refugee camps in Ethiopia and Kenya and shared a history of vulnerability in the region.

Conflict has significantly affected the Somali-inhabited territories since the 1960s. Following independence from Britain and Italy, Somali nationalists tried to unite all Somali territories under one nation. The venture usually called Greater Somalia put the newly independent country on a collision course with neighbouring Ethiopia and Kenya, where a big Somali population has always lived. The 1977–78 Ethiopia–Somalia war, also known as the Ogaden war, displaced close to 1 million Ethiopians, mostly Somali, who took refuge in Somalia until 1990 (Lewis, 2002). Towards the end of the 1980s, when the civil war in Somalia intensified, a reverse exodus started. Millions fled the country and took refuge in Ethiopia and Kenya as the state of Somalia eventually collapsed. In 1988, Hartishek refugee camp, right on the border with Somaliland, was the largest refugee camp in the world, hosting over 400,000 refugees. In 1991, when Somaliland declared its independence, most of them returned to Somaliland and those remaining were relocated to Kebribeyah, a camp further away from the border (Van Brabant, 1994; Hammond, 2014) that we have included in our study. Since 2008, the conflicts in southern and central Somalia and recurrent drought have displaced hundreds of thousands of people. This has resulted in the establishment of five refugee camps in Dollo Ado, which we discuss later in the chapter.

In this situation, some of the fleeing population were categorised as returnees from Somalia and others as Somali refugees. However, it was difficult to differentiate returnees from refugees in the Somali hosting refugee camps located in the region (Carver, 2020). In such a context, the concepts of ‘hosts’ and ‘refugees’ among the Somalis affected by displacement become fluid. This has recently been recognised by government and humanitarian organisations. In their June 2023 memorandum of understanding to initiate durable solutions for Kebribeyah, the Refugee and Returnee Service (RRS) and UNHCR stated ‘The implementation of the MoU will formalise Kebribeyah residents: refugees, and hosts as one community.’ This resonates with our argument to consider everyone part of a displacement-affected community.

The concept of displacement-affected community lends itself well to the Somali-inhabited territories of the Horn in general and the camps and their surroundings in particular. Refugee camps in the Somali region of Ethiopia are situated in the middle of displacement-affected communities – either living in displacement or displaced in the past. Thus, in the Somali context, the displacement-affected community constitutes those who have refugee status, the host community (who may have been refugees, returnees or internally displaced either due to conflict or drought) and the diaspora. In other words, most of the people who are being labelled as ‘refugees’ today were ‘hosts’ in Somalia. Furthermore, the Somali Regional State is currently hosting about 1.2 million IDPs displaced as a result of drought and conflict, and some of the IDP camps are located quite close to the refugee camps. These multiple overlapping categories of displacement-affected people share not only a history of precarity and geographic locations but also language, kinship, cultural practices, religion, livelihoods and survival strategies. The livelihoods, economic activities and interactions between communities are shaped by local socio-cultural contexts – clan, religious and ethnic networks. Therefore, it is practically meaningless to separately consider one or two of them in interventions and academic discourse.

In big cities such as Addis Ababa, given the large number of people the proportion and the intensity of those affected by displacement is lower than in the camps and their surroundings. Nevertheless, a few areas such as Bole Michael (with a concentration of Somalis) and Gofa Mebrathayil (with a concentration of Eritreans) have many features of displacement-affected communities.

Ethiopia has long welcomed refugees and in January 2025, the country was the second-largest refugee hosting country in Africa, after Uganda, with people fleeing conflict, drought and human rights violations in neighbouring countries, including South Sudan, Sudan, Somalia and Eritrea, but recently also Yemen, Syria and countries further afield (UNHCR, 2025). The Ethiopian government adopted a national Refugee Proclamation in 2004 based on the international and regional refugee conventions to which Ethiopia is a party (the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, and its 1967 Protocol and the 1969 OAU Convention). Additionally, Ethiopia is a signatory to the Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework (CRRF), set out in the 2016 New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants. The Ethiopian parliament adopted a revised proclamation in January 2019, giving refugees the right to work and reside outside camps, access social and financial services, and register life events, including births and marriages. However, refugee experience has shown that this is difficult for them to achieve in practice because of delays in implementation. There are also stringent requirements for paperwork, and language is a significant barrier. What this means in practice is that most refugees, whether registered or not, are not in formal employment. They are, however, active in informal businesses and work across the three locations studied and especially in camps where there is more demand for their services and less restrictions.

According to the latest statistics from UNHCR (December 2024), there are 361,949 Somali refugees, which is 34% of the 1,073,275 refugees and asylum seekers the country is currently hosting. These are mainly from South Sudan, Somalia, Eritrea and Sudan hosted in 24 refugee camps spread across five states. A further 79,000 live in Addis Ababa. Of the total number of refugees, nearly half are women and girls. Refugees have arrived in concentrated groups associated with particular events – after the conflict in Somalia, the peace treaty in Eritrea, and from both South Sudan and Sudan.

Camp refugees have depended on humanitarian assistance in the past but as this has shrunk they have relied on their own informal economies and networks of care, which is what this chapter focuses on. Additionally, Ethiopia has one of the largest numbers of internally displaced people (IDPs) estimated at 4.4 million, though the figure changes very fast as many IDPs leave camps to return to their homesteads. Ethiopia is a signatory to the 2009 African Union Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons, also called the Kampala Convention.

On both of these issues the government and humanitarian organisations responses have mostly focused on humanitarian assistance – which is reactive rather than proactive and preventive. The main policy framework for addressing IDPs is the Disaster Risk Management (DRM) policy of 2013. There is an IDP Advisory Group (comprising the UN Resident/Humanitarian Coordinator, the UN Office for the Coordination of the Humanitarian Affairs, IOM, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), the International Committee of the Red Cross and the Danish Refugee Council), and a national steering committee (under the leadership of the Deputy Prime Minister).

In 2017, Somali state set up a Durable Solutions Strategy and Durable Solutions Working Group (DSWG). The Somalis are suffering from protracted displacement situations in IDP camps located in many parts of the Somali region, in refugee camps and in Addis Ababa. At the same time, Somalis have a reputation for being entrepreneurial and have successfully mobilised their skills in the camps with the help of large diaspora networks in other parts of Africa and beyond. However, their potential has been constrained in Addis Ababa due to legal constraints on refugee entrepreneurship. They may work informally for other business people but their situation has continued to be precarious and protracted.

The research process

Site selection and community profiles

We chose three sites with different manifestations of the protracted displacement economy: the capital city of Addis Ababa and two camps, Dollo Ado and Kebrebeyah. Addis Ababa is currently hosting over 79,000 registered refugees who are either under the Out of Camp Policy (OCP) or the Urban Support Program (USP). The OCP, started in 2010, was a special programme for Eritrean refugees allowing them to live outside camps if they could forfeit humanitarian aid and obtain an Ethiopian guarantor. USP is a programme for refugees who need medical treatment that they could not access in the camps or if they require special protection. All of the Somali registered refugees in Addis Ababa in our study were on USP and most of them for medical reasons. The locality of Bole Michael in Addis Ababa was established by Somalis who had experienced displacement at various points in time. The economy in Bole Michael is still very much linked to the displacement economy. The presence of numerous money transfer (hawala) companies is proof of Bole Michael significant place in the Somali displacement economy. There are more than 48 ‘companies’ providing translation services for Somalis coming from refugee camps or from one of the Somali-inhabited territories in the Horn of Africa and to the Somali investors, most of them coming from the diaspora.

Established in 1990–91, Kebribeyah is one of the oldest refugee camps in the country. Besides Kebribeyah, there are two refugee camps around Jigjiga: Awubare and Sheder. The three make up the ‘Jigjiga cluster’ in the official documents of UNHCR and the Ethiopian government’s Refugee and Returnee Service (RRS). Multiple commonalities between the ‘refugees’ and ‘hosts’ – similar language, religion, cultural practices and history of longstanding displacement and vulnerability – blurred the boundary between displacement-affected communities. The economy and livelihood strategy of this population is very much shaped by the longstanding displacement situations.

The displacement situation in Dollo Ado presents a different context. The so-called ‘Dollo Ado cluster’ constitutes five refugee camps established between 2008 and 2011. Listed according to their distance from the border with Somalia they are: Buramino, Kobe, Haleweeyin, Melkadida and Bokolmayo. All are situated within a radius of 75km. The closest camp to the border, Buramino, is located 20km and 40km from the Somalia and Kenya borders, respectively. They are situated in rural areas next to small towns where the ‘refugees’ are much more numerous than the ‘host’ communities. The district’s town, also called Dollo Ado, is the commercial town of the region and is located right on the border with Somalia. The town on the Somalia side is called Dollow and the two are separated or connected by a bridge. The displacement economy in the region has been shaped by its location on the border. The Dollo Ado cluster is a showcase of government and UNHCR intervention in supporting the displacement economy.[1]

Fieldwork was conducted in three stages: the first between February and April 2021, the second between February and March 2022, and the third between March and July 2023. While the three stages of fieldwork were planned, the team usually systematically integrates coincidences/new developments as an opportunity to analyse the situation of displacement-affected communities and the protracted displacement economy. In 2022, the displacement-affected communities in the Somali Regional State were under terrible stress as a result of drought. About 2.3 million heads of livestock died in the Somali Region, constructions stopped because of water shortages and business was less active owing to the weak purchasing power of the people. Kebribeyah was the epicentre of the drought, and legal constraints meant that displaced communities were affected much worse than others. In May 2023, we arrived at a ‘time of berwaqo’ (prosperity), as one informant said; thanks to sufficient rainfall, livestock business was active and wage labour was plentiful as constructions and rain-fed agriculture resumed.

The situation in Dollo Ado was relatively better during the 2022 drought because of its location near Genale River, and the involvement of part of the population in irrigation agriculture. The third round of fieldwork in Dollo Ado took place in July 2023, about two months after food aid was suspended by the World Food Programme (WFP) following an allegation of aid diversion by officials. As a result, the business centre in Dollo Ado, which had been vibrant in 2022, looked like a deserted town. Many people left to look for wage labour in the nearby towns to support their families. Many others crossed to Somalia and Kenya to look for support from humanitarian organisations and kin. This indicates how much humanitarian assistance had underpinned the displacement-affected communities’ business and how its withdrawal plunged them into precarity and vulnerability. We examined how the increased vulnerability affected displacement-affected communities’ already precarious livelihoods and how they responded. In particular, we were able to delve into the crucial importance of local solidarity in the form of sharing food, goods and loans.

The research had been conducted in a very challenging environment. The country had been facing multiple problems including Covid-19 and the war in northern Ethiopia. We started fieldwork at a time when Covid-19 was still causing panic, and the country was under a state of emergency following the war in Northern Ethiopia. As a result, several meetings and community engagements had been cancelled. In addition, there had been conflict in several areas of Oromia, and the route to Dollo Ado was closed forcing the research team to use an alternative route that took longer and was more uncomfortable. This route was also not safe because it crossed territory that Al-Shabaab had tried to take over in September 2022. We were advised not to conduct research in Dollo Ado owing to fears about Al-Shabaab’s activities. Ethiopian government armed forces foiled Al-Shabaab’s attempt to penetrate into the Somali Region and an attack on a military base in Dollo Ado in September 2022 and June 2023, respectively.

Quantitative methods: baseline and panel surveys

Due to the absence of an accurate and up-to-date list of households in the selected research sites in national-level household survey or administrative data to be used as sampling frame, we applied a two-stage probability-sampling strategy (a structured walk and spatial sampling technique using administrative data from UNHCR). For the first survey in our study sites we first used the administrative data from UNHCR to identify the research sites and estimate the size of the population which used probability-proportional-to size sampling (PPS) to sample clusters. The second stage used a structured walk as a form of systematic sampling to sample respondents. Field workers were trained and instructed to walk clockwise from the centre of the research site, skipping 10 housing structures from the first selected household to randomly select the sample household. To summarise, our sampling strategy followed two stages; the first identifying and sampling clusters within each research area; and the second sampling households within each cluster. The aim of this sampling strategy was to collect data that represented the displacement-affected community in each study site as accurately as possible.

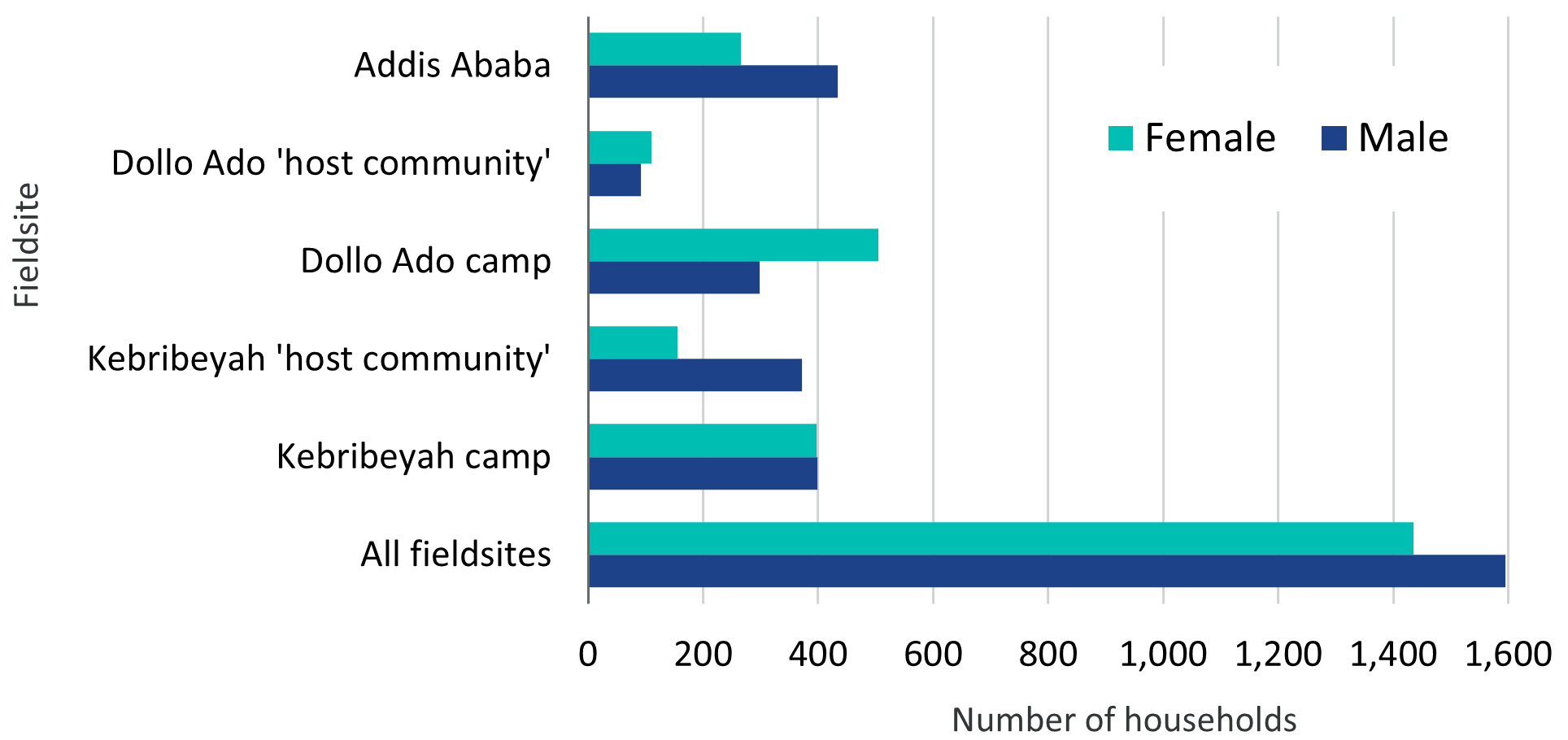

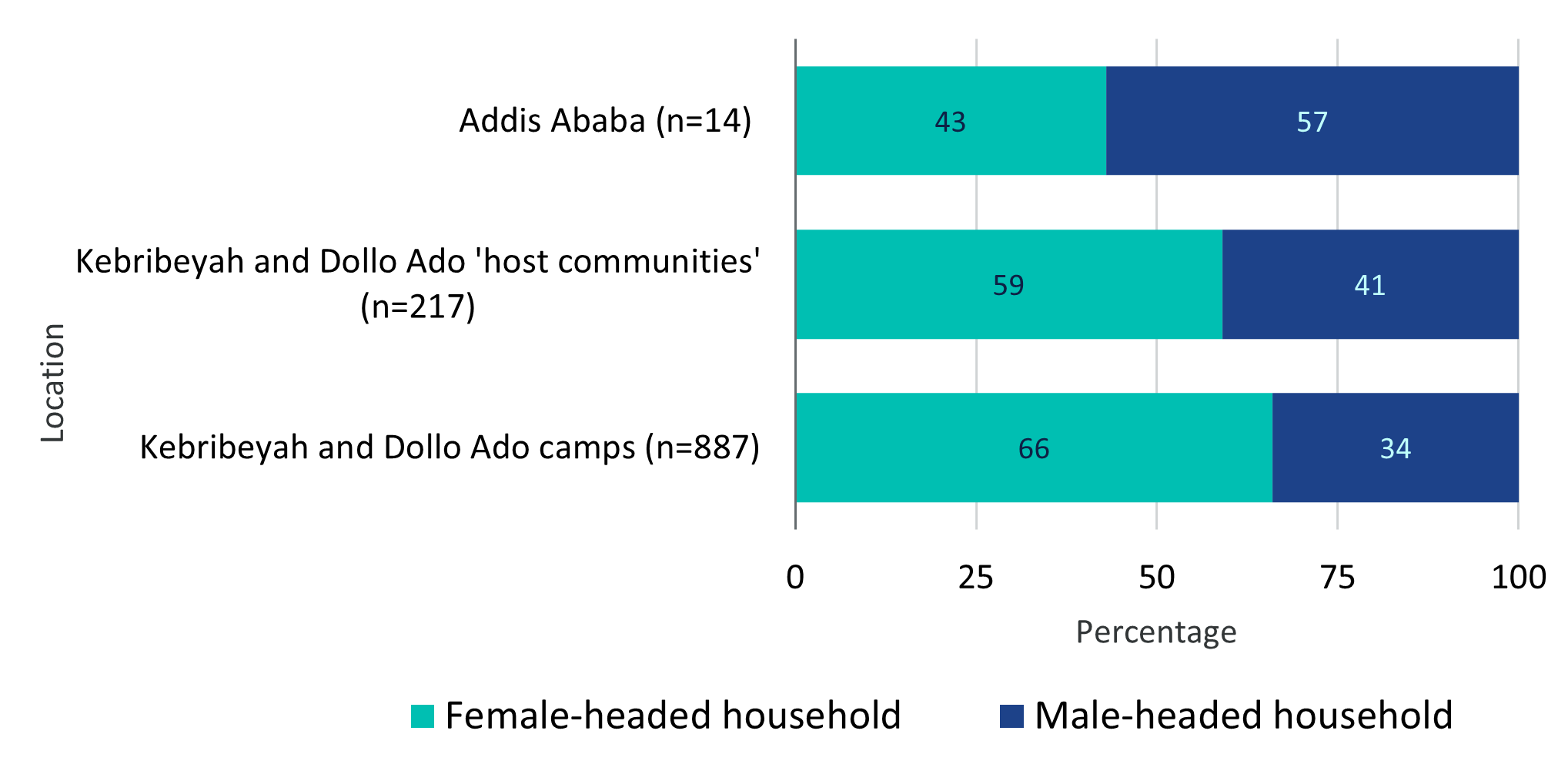

The PDE Ethiopia baseline survey was conducted in 2021 and covered 3,031 households in five enumeration sites (Addis Ababa, Kebribeyah Camp and community, and Dollo Ado Camp and community). Sampling was at the household level and we sampled every 10th house, regardless of the sex of the household head, and in each selected household we asked the most knowledgeable member to respond to the survey. Figure 2 shows the distribution of the households by the sex of the head across the research sites.

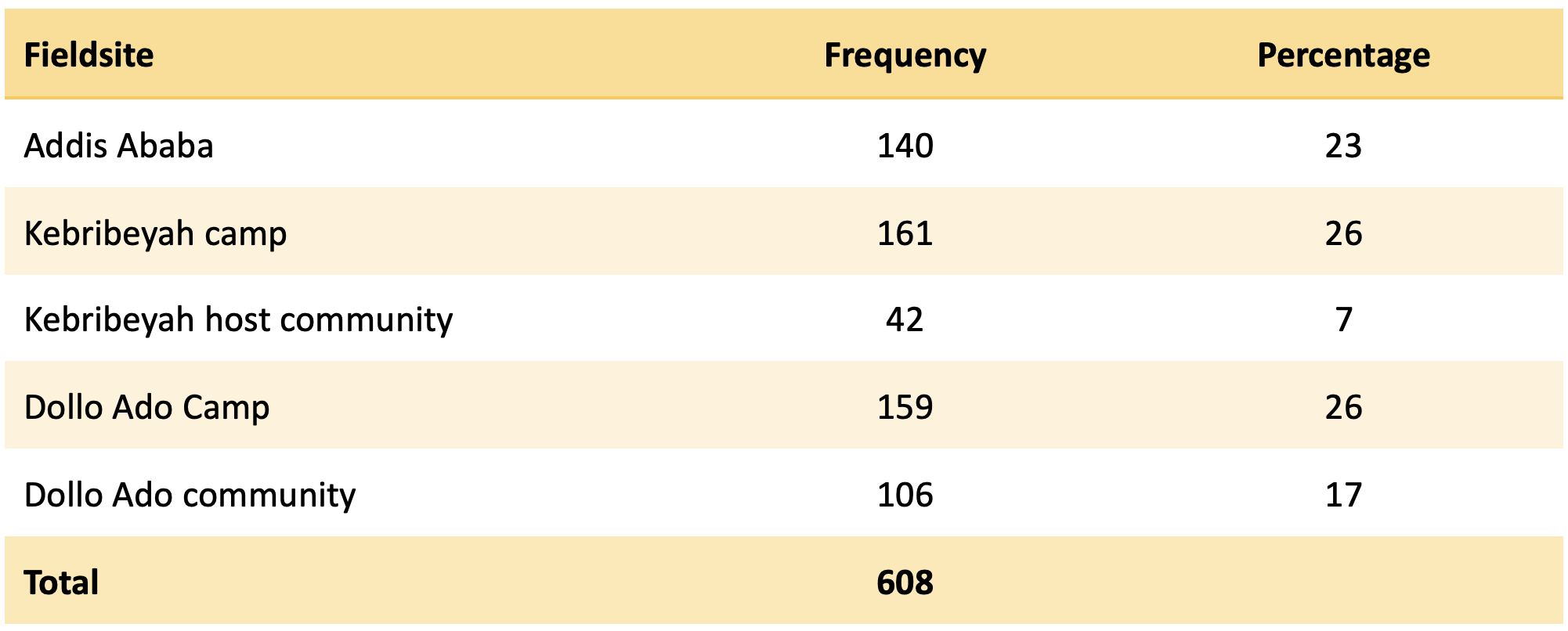

A follow-up survey was conducted in 2023 on a 20% sub-sample of the 3,031 baseline households. A total of 608 households were randomly selected and interviewed during the follow-up survey. The distribution of the second round panel household is shown in the table below.

Qualitative interviews

We used qualitative methods to build knowledge inductively in exploring protracted displacement economies. Using in-depth interviews and oral history narratives we attempted to obtain a deeper understanding from the perspective of refugees. Our goal was to provide a rich, contextualised understanding of the displacement-affected communities in each location. The raw data was translated from Somali into English to yield verbatim transcripts and imported into NVivo for analysis. Data was coded for each theme and category of participants, based on gender, age and location, and used to identify common themes across all types of information gathered. We tried to reflect their views and experiences by going through coded and transcribed data to compare responses. In the course of our analysis, we distinguished between information that is relevant to all (or many), in contrast to aspects of the experience that are unique to particular households in the different sites (camp and urban).

In addition, we read and re-read the interview transcripts in an iterative analysis process, to understand the subjectivities and lived experiences of displacement. We made constant comparisons between the different sites to allow diverse perspectives and experiences to be captured in relation to the lives of displacement-affected populations, and to gain insights on the protracted displacement economy in Ethiopia. Through our rigorous inductive analysis, along with the use of triangulation, we believe that our conclusions are credible and robust.

Production of documentary films

Using filmmaking as part of a research project in Ethiopia was a novel experience. Initially we were not familiar with the process and did not know how the training and the output would be used in the project. However, we managed to attract enough applicants to select from for the filmmaking training. An intensive 10-day filmmaking workshops was held as part of the research project. Filmmakers with some basic filmmaking experience were selected to take part. In the workshop, the filmmakers were encouraged to devise ideas that resonated with the Protracted Displacement Economies research project themes, for example, mutual aid, feminist economies or financial and non-financial transactions. During the workshop, the filmmakers researched ideas, developed them, filmed and then edited them. In the film The Translator, the filmmakers found a young Somali woman named Nasteeho, living in Bole Michael, Addis Ababa. She recounts her experiences of moving to Ethiopia and how difficult it was to communicate – which meant her family relied on translators to help them for their daily needs. This was costly and gave her a passion to become a translator herself. She now works as a translator helping newly arrived Somalis with issues such as finding accommodation and support in hospitals. Her story shows how displaced Somali youth in Addis Ababa are involved in language translation for a living.

The translator

A film by: Zewdu Lingerh; Dagim Mesele; Mikias Dawit

Nasteeho came to Addis Ababa as child after becoming displaced from Somalia. Speaking no Amharic at the start, she is now a translator for Somalis in Addis Ababa.

5:49 mins; Amharic and Somali with English subtitles, 2022.

In the film Naima, the filmmakers were interested in the women who herd goats near Bishoftu, where internally displaced communities live. This film was a day in the life of Naima, a woman who is responsible for much of her family’s existence – she herds the animals, sells produce at the market and takes care of the house. This is in contrast to her life before displacement, when she had a successful hotel. The film captures her struggles and resilience in a sensitive manner revealing the role of women in the displacement economy.

Naima

Naima was a comfortable woman until war came and destroyed everything. Now she juggles housework, breeding goats and selling at the market to support her family.

6:51 mins; Amharic and Oromo with English subtitles, 2022.

The two films produced as a result resonated very much with the protracted displacement economy research findings. Both films not only showed the precarious life of displaced peoples, but also their resilience and agency within the existing legal constraints.

Stakeholder engagement

We started the research with a meeting in Bole Michael with members of the Somali Refugee Central Committee (RCC). Our discussion was mainly on general issues such as changes and continuities in the policy landscape, and enablers and constraints in refugees’ involvement in the economy. We had held two meetings with broader representations of stakeholders in the country: on 3 July 2021, and 14 March 2023. The first one was a webinar, since there were restrictions in place on physical meetings during the peak of the Covid-19 pandemic. This engagement was very helpful in introducing the project to broader stakeholders representing the federal government, humanitarian organisations and researchers. As the first meeting with stakeholders, our discussion was focused on our methodology and conceptualisation of displacement-affected communities.

The second stakeholders’ meeting was conducted after two stages of fieldwork, partial analysis of the data and the availability of preliminary findings from both the global and national research. National and local contexts were set by government officials representing refugees and the returnees service (RRS) and Somali Regional State. The meeting resulted in productive discussions involving UNHCR, INGOs, local NGOs, research institutions, and migration departments of embassies and the Ethiopian government ministries.

Key findings from Ethiopia

Feminist economies and mutual aid

In the absence of sufficient humanitarian and host government assistance, displacement-affected communities rely on support from neighbours and others including local charity networks and diaspora neighbours who provide each other with food, non-food items and cash. In times of need, for example, when there are delays in receiving food aid, during bad droughts and the suspension of food aid by humanitarian organisations, help from neighbours and from those further afield such as the diaspora are crucial. When support from a single neighbour is not enough, it is common to organise a collection of contributions from the neighbourhood and beyond. The research team witnessed such collections in April 2022 in Kebribeyah when drought, shortages of water and inflation made life very precarious for the displacement-affected community. A similar system was seen in Dollo Ado in June and July 2023 when food aid was abruptly suspended by the WFP, putting the livelihoods of the displaced communities at risk.

One of the essential values we observed among Somalis affected by displacement in Ethiopia, both in camp and urban settings, was the spirit of helping others to restore dignity in times of need. They help each other and in this way the aid is mutual and collaborative. It is different from the services they receive from government, non-profit organisations, and/or international actors such as UNHCR because the care comes from the displacement-affected community itself and prioritises those who are most vulnerable. It is based on an intimate understanding of people’s vulnerability through everyday interactions and observations. It is thus a highly effective way of targeting the beneficiaries of assistance as these are chosen on the basis of community knowledge rather than databases, since the latter may miss out the most vulnerable who tend to be undercounted in surveys and therefore less visible.

We observed that in such systems of mutual aid, networks and clan membership create bonds of social cohesion. In Addis Ababa, where the displacement-affected community is relatively small, they socialise with and rely on support from other refugees, and in some cases on non-refugee Somalis as well. Interactions and support are typically facilitated through shared language, religious values, culture and clanship. These are important for both men and women but take different forms through their social networks. International organisations mainly provide financial support, which can only cover basic survival, and most areas have seen an erosion of such support recently increasing the importance of other forms of mutual aid.

Displaced communities are exposed to a number of vulnerabilities that are emotional, psychological, social and economic. In the course of their challenging lives as refugees, they have learned how to cope and adapt through their social and economic connections with each other. They are acutely aware of their connectedness and dependence on one another as a means of survival. They appreciate the role of mutual care when their lives are fraught with hardship and chaos and care is seen as the foundation to build their communities.

It is evident that longstanding displacement and vulnerability has created strong social cohesion and a sense of interdependencies among the Somali community. A good example is shahad. Shahad is a handout to a person who is familiar or a distant friend. People ask for money from acquaintances and ‘friends’ to buy something small, usually food, and khat (a leaf containing stimulants that is chewed). ‘Give me shahad for…’ is commonly heard in the streets, coffee/tea places, bars, shops and offices where people are seen asking for such help. The importance of shahad in the everyday lives of the displaced Somali community is reflected in interviews conducted in all research sites. In Kebribeyah, our informant stated that, ‘Men live on shahad and children live on their mothers’. Shahad is not always mutual, however, and may not be reciprocated materially or in the same form as the original gift. It can be repaid in other ways. For example, giving shahad enhances the social standing of the person giving the money and the recipients also build up the image of the giver as generous. This is important particularly if the giver competes for an office, often influential clan leaders or elders, and the recipients can reciprocate by campaigning on his or her behalf. Our survey shows variation in mutual support across the sites. Mutual support and solidarity decrease as one moves from peripheral camps and their environs to the capital city. This might suggest differences in the degree of social cohesion in different socio-spatial settings. Communities in the camp and rural sites are tightly knit due to shared experiences of displacement and/or vulnerability. These may be less significant in larger cities in Ethiopia.

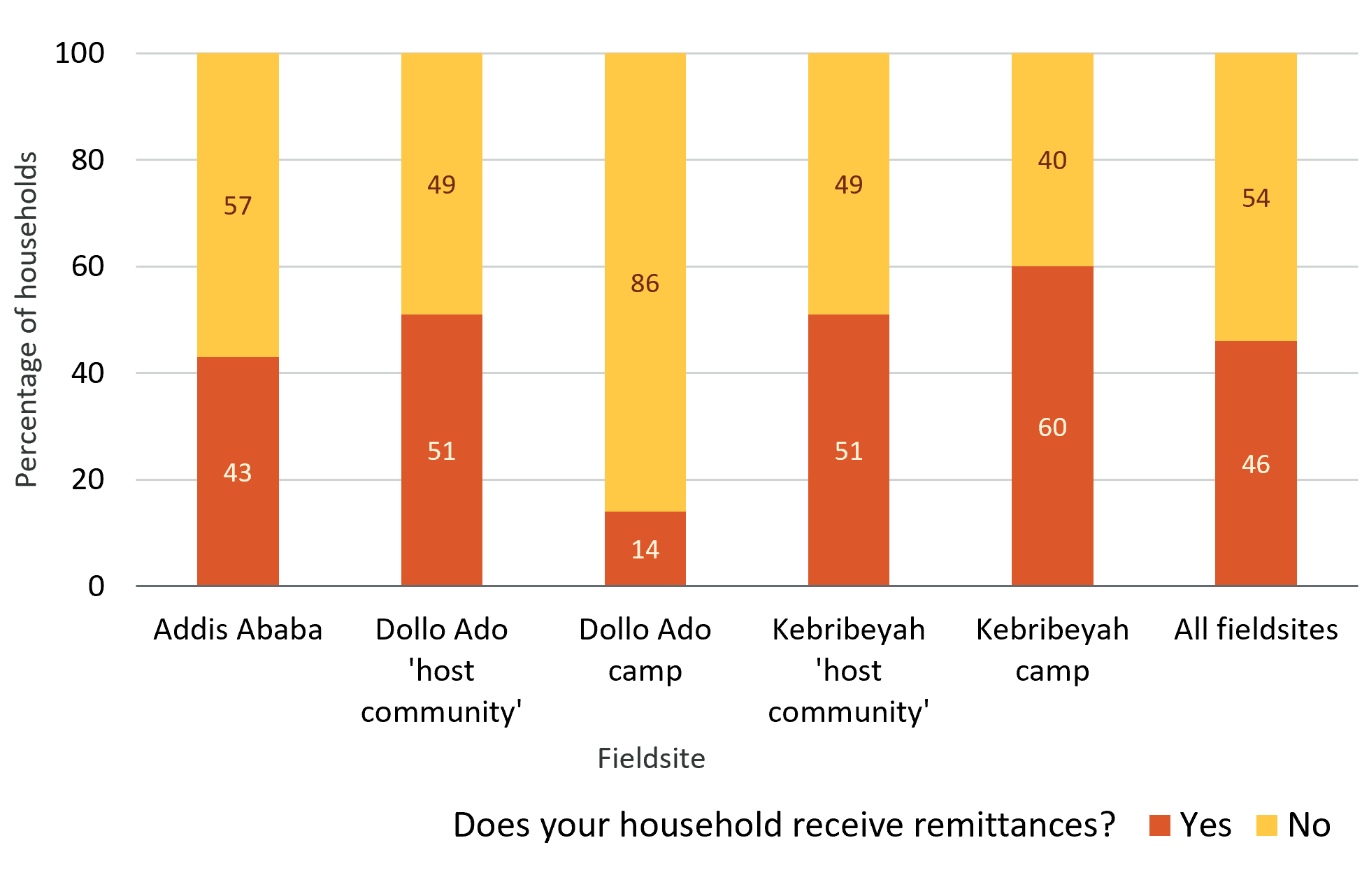

Our qualitative data shows that the contribution of the Somali diaspora is crucial in supporting those left behind. Besides remitting to their family members and friends, the diaspora contributes to supporting people and projects in their original neighbourhood and the refugee camps they once lived in. For example, they organise fundraising for the most vulnerable members of their neighbourhoods. Most of the diaspora involved in providing support were former refugees in one of the camps in the region. Hassan, a 24-year-old refugee supports his mother and his four siblings, including his brother who has mental health problems, with the income he generates from his bajaji (autorickshaw). Kamal bought the bajaji for 400,000 birr (US$7,500) in December 2021. He got all the money in the form of remittance from five of his former friends and classmates who were resettled in the United States. They discussed among themselves and asked him what he could do if they sent him money, and he responded that he wished to buy a bajaji and start a transportation business with it. Asked about his relationship with them, Hassan responded, ‘They were just my friends, not even from my clan. Of course, we are all Somalis.’ Hassan’s close friend, Adan, has a shop in Kebribeyah refugee camp. When his friends asked him what he would do with money sent to him, Adan told them that he would like to open a retail shop. Four of his former friends who live in Minnesota, United States, sent him US$1,000 each. Now Adan’s shop is a favourite among many people in the camp. During the 2023 Ramadan, Adan received US$350 from another two friends, both living in the United States. The holy month of Ramadan is when many households receive remittances as the senders consider it a religious duty. During Ramadan, many households who neither have a relative nor a close friend receive between US$50 and US$100 from the fund the diaspora mobilises to support the poor who are left behind in the camp.

Not all displacement-affected communities have access to remittances. According to our survey, about a quarter of the households reported that at least one member of the household lives elsewhere. A higher percentage of households in Kebribeyah community and Addis Ababa reported that they have at least one household member living elsewhere. A comparatively small percentage of households from Dollo Ado reported that they have household members living outside the household. Kebribeyah, with refugee camps older than three decades, has benefited from the resettlement of many displacement-affected community members, whereas Dollo Ado, with its relatively recent establishment of camps and its location in very remote areas, has not had similar advantages. Interestingly, in Kebribeyah the difference between the camp residents (‘refugees’) and the Kebribeyah community (outside the camp, so officially non-refugee), in terms of family members living elsewhere is insignificant.

There are other arrangements for support as well and these are not always mutual. We interviewed Kamal, who was a religious teacher, in Kebribeyah refugee camp. He does not have any relatives abroad. However, he receives remittance from his former students occasionally. For the 2023 Eid al fitr he received US$400 from four of his former students. Several of his former students do the same irregularly. Kamal had over 70 goats that he had bought from the remittances he had received in previous years. He reciprocates these with du’a (prayer). His former students request him to perform du’a for them every time they remit money to him. Ikanda (2025, forthcoming) wrote that many Somalis who lost loved ones in the diaspora as a result of complications caused by Covid-19 requested their relatives at home to perform proper funeral rites because they were dissatisfied with the interment process in foreign settings.

There are two other systems where religion reinforces the Somali socio-cultural practices of supporting each other: sadaqa and zakat. Sadaqa is a form of giving/taking in a context of vulnerability. Many individuals in need move around in the camps, towns, shops and hotels and are given money, food and other items. The difference between sadaqa and shahad is the relationship between the giver and the recipient and the amount of the money given. While sadaqa is given to any needy person, shahad is given to a familiar or distant friend and the amount is also a little bit higher in the case of shahad. Giving sadaqa is considered religious because handouts to very destitute people is considered pleasing to Allah. Zakat is more systematic religious alms that the better-off households pay once a year. Gallien et al. (2023:6) presented zakat as ‘the world’s largest system of non-state welfare provision… One of the five pillars of Islam, zakat describes an annual obligatory payment of a percentage of productive wealth to a set of appropriate recipients, including the poor.’ Similarly, even in the context of displacement, many people in the refugee camps and outside give zakat once a year, commonly at the end of Ramadan. Kamal, cited above, gives one or two goats in the form of zakat to his poor neighbours every year. Mohammed, a shop owner in Buramino camp, Dollo Ado, gave 25,000 birr [US$500] last year. He divided this between his destitute neighbours and his family members who live in Somalia. According to Mohammed, their displacement situation makes payment of zakat more important as there are more needy people than in a situation of normal life. Such webs of support are common among the Somali (both ‘displaced’ and ‘hosts’) and seems to have developed in the decades of displacement, poverty, history of communal life and Islamic culture.

Here we draw on feminist economics in the analysis of the protracted displacement economy that calls for awareness of gender differences in experiences of displacement, power relations and gendered roles and entrepreneurship (Lyberaki, 2011; Olmsted, 1997). Such an approach has guided us to look into aspects of the protracted displacement economy that have hitherto remained less visible, such as the multiple roles of care and social reproduction performed by women within the family and displacement-affected community. Our findings have shown that the care economy, which is highly gendered, is critical in situations of deprivation, instability and vulnerability where official assistance cannot be relied upon. Crucially important is women’s intimate knowledge of the needs of women and girls, the elderly and children, and ethnic minorities in their local refugee community. Formal refugee support may overlook such groups and their needs and fail to achieve equality, equity and social justice that they try to. Women care not only for their own families but other women and men in the community. Care is provided in different ways depending on who receives it and it is largely unpaid and may not be reciprocated.

There is a cultural understanding that men are not expected to reciprocate the support they receive from women because women are socially and culturally constructed as caregivers and nurturers according to patriarchal norms in Ethiopian society. On the other hand, women and girls help each other by providing care, household help and cooking services for their friends and neighbours. They also share their own food with other vulnerable women in the community. Unmarried young women help older women with household chores and are at times ‘loaned’ out for care work, which can be paid. An example is when women ask other women in the neighbourhood to look after their children to enable them to go out to work and earn. This kind of support has allowed women with young children to gain access to informal employment opportunities.

There are other kinds of women-to-women help that are hidden; for example, a Somali woman in Bole Michael said that she offers massage services to pregnant women and is remunerated in cash or in kind.

Based on our findings, we believe that these contributions need to be recognised in refugees’ survival and coping strategies in discussions on protracted displacement economies. At the same time this should not absolve governments and international refugee agencies from their responsibilities in ensuring that female refugees are given the resources and conditions to live a life of dignity and well-being.

Local solidarity and debt

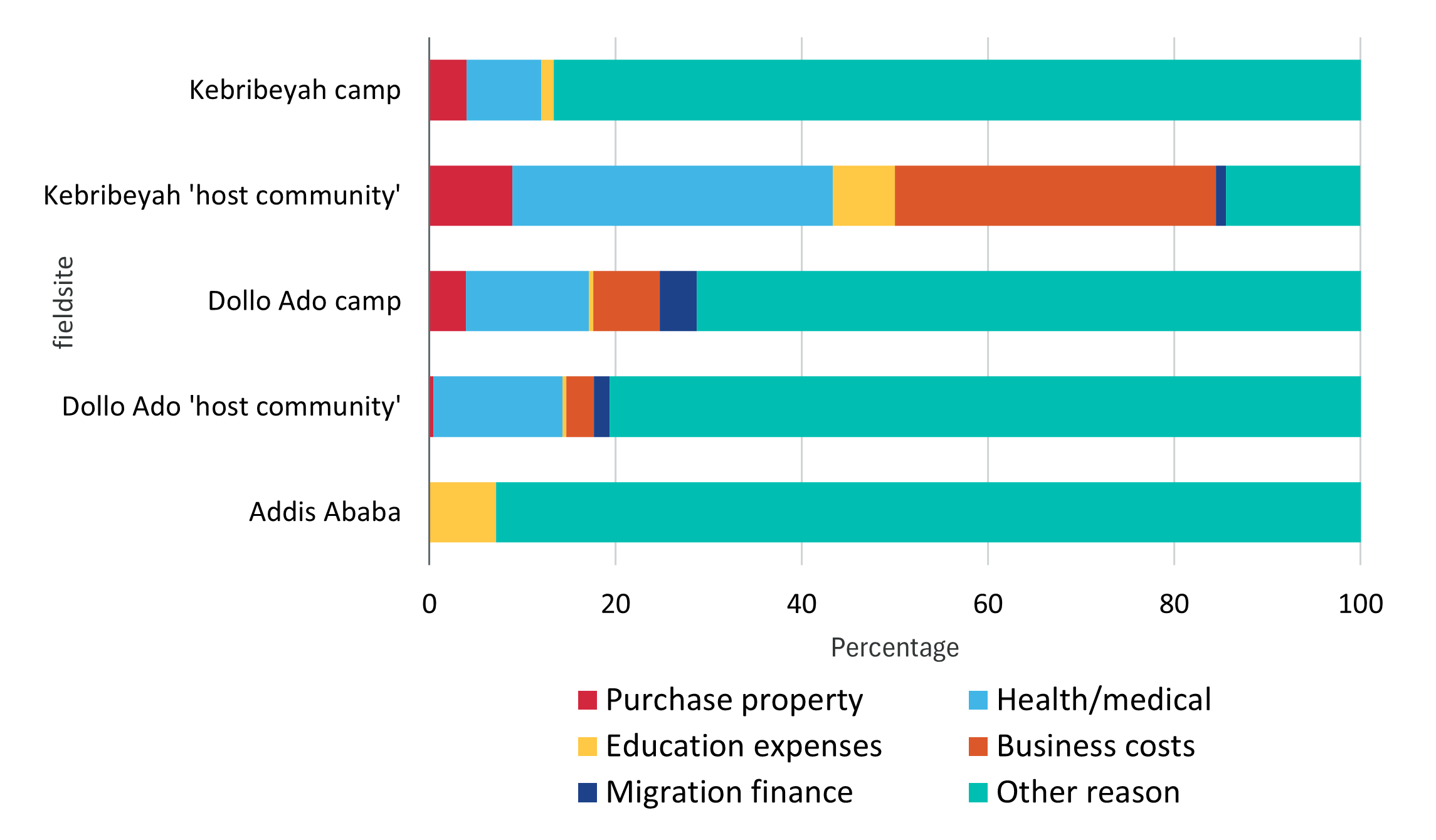

Credit and loans play a crucial role in the survival and well-being of the displacement-affected communities. Giving goods on credit could be considered part of both local solidarity and a business model. Though there are some differences between sites in practice, debt is an important part of the way people who are affected by displacement live. Particularly during critical moments, such as the delay or suspension of food aid, many households depend on borrowing. Our survey, which was conducted during a relatively normal time (when there was regular distribution of food aid and no critical drought), shows that 37% of households had some form of debt. Sixty-seven per cent of debts were to shops and 26% of the debts were to family and friends. Due to the Ethiopian government’s policy that denies refugees access to official loans, only 3% of debts are from formal financial institutions. Most of those who were in debt in camps and rural community settings were women (wives and mothers). This is because women bear the responsibility of feeding and nourishing the family. The debts are interest free, which means people just pay back what they had borrowed. In our survey, it is only in Addis Ababa that the majority of debt recipients were male; though this might be related to our sampling. Seventy per cent of survey participants in Addis Ababa were not the displaced population, which means the majority of the males taking on debt might not have refugee status. Figure 4 shows the relationship between debt and gender in Addis Ababa, in the camp and ‘host’ community contexts.

The purposes of the loans were also asked in the survey. As the following table shows, the largest category was ‘other’, which was not specified. However, our qualitative data clearly shows that debts taken from shops are for food and other everyday essentials which reveals the critical importance of debt to the households. Figure 5 shows households’ reasons for taking on debt in different locations.

During our fieldwork in July 2023, when the displaced people had been without food aid for a third month due to aid suspension, many of the households were relying on loans they were getting from shops. Amina, a woman shop owner in Buramino town, had lent over 200,000 birr (US$3,600) in credit in the month of June 2023. Amina was also getting most of the goods for her shop in credit from a wealthy shop owner in Dollo Ado town who was a member of her clan. Even in a situation of uncertainty, such as suspension of food aid, Amina and other shop owners continued to give loans and credit. This could be because of a reciprocal relationship built on longstanding co-existence in the situation of vulnerability, including kinship, religion and neighbourliness. Amina asserted that she continued to give goods on credit when she was not certain whether her customers could pay or not because it was a crucial means of survival for the displacement-affected community’s households. For a wealthy wholesaler in Kebribeyah who was known for giving credit to shops situated in a refugee camp, this emanates from a common history of vulnerability, and a sense of reciprocity. He said:

We know each other in a different context. I was a refugee in Somalia. Then they [the present refugees] helped us. Many people in the camp have relatives outside the camp… We are the same people.

In normal circumstances, debt in Dollo Ado is intertwined with sales of wheat from the monthly ration. The humanitarian organisations adopted two different approaches in Kebribeyah and Dollo Ado. In Kebribeyah, rationed food was partly replaced by cash a few years ago. In Dollo Ado, they continued to provide food aid in kind (cereal, mainly wheat, salt and oil) on a monthly basis. The rationale was, according to WFP, to replace the ration distribution with cash based on the local contexts, particularly depending on the availability of markets to buy food. Kebribeyah camp was among the first to implement this because of its location in Kebribeyah town, only 50km from Jigjiga, the regional capital.

Secondly, in Dollo Ado it was argued that there was no market that could cater to over 200,000 refugees in a remote part of the country where the local community also mainly lives on food aid that comes in different forms. In Dollo Ado, refugees usually sell a substantial amount of the wheat they receive (Betts et al., 2020). Although technically illegal, this was a licit measure from the people’s perspective for two reasons. First, the kind of food they are provided was not based on their cultural preferences and traditional diet. Indeed, they had requested that the WFP replace wheat with rice. Their rationale was ‘wheat is not part of the Somalis’ food culture’. However, WFP’s response was that the kind of cereal they provide is determined by the availability of aid and cannot be adjusted according to the needs of the people. Second, the amount of food aid is not only insufficient but also an incomplete package, for example, many families need milk for their children but it is not included. Some might need sugar, certain spices or non-food items. Thus, as their only source of income, they had to sell part of the food aid to buy those other crucial needs. This gradually created a big business in Dollo Ado camps, where refugees sold wheat and bought rice, spaghetti, macaroni, milk and other goods. Due to the relatively large size of the refugee population, the business attracted many traders. Many shop owners in and around the refugee camp were involved in this trade. Flour factories were established in Dollo Ado town and beyond, resulting in increasing demand for wheat. In this context, many of the shop owners expected their debtors to repay their debt in wheat, not money, which helped them to acquire as much wheat as possible.

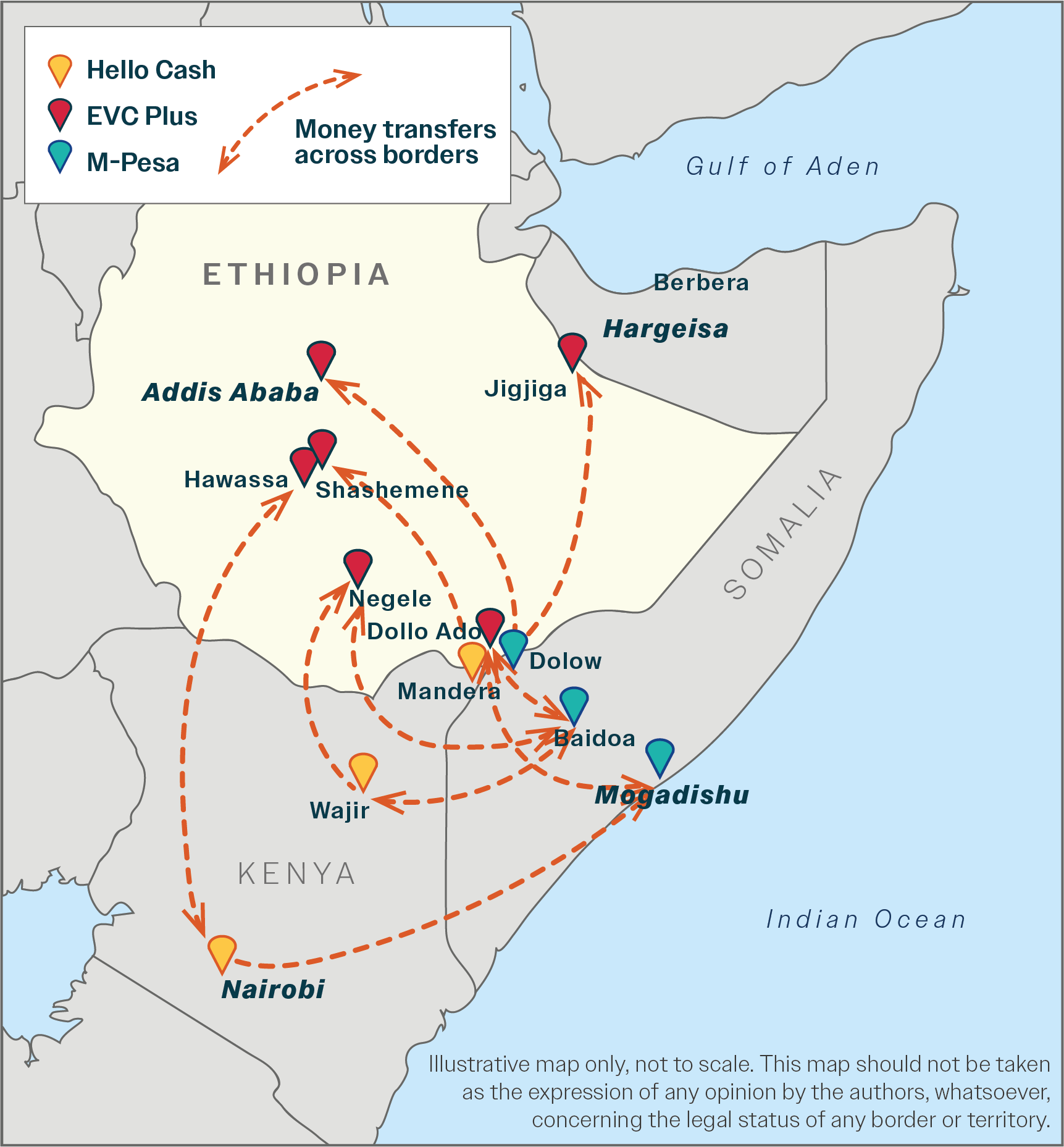

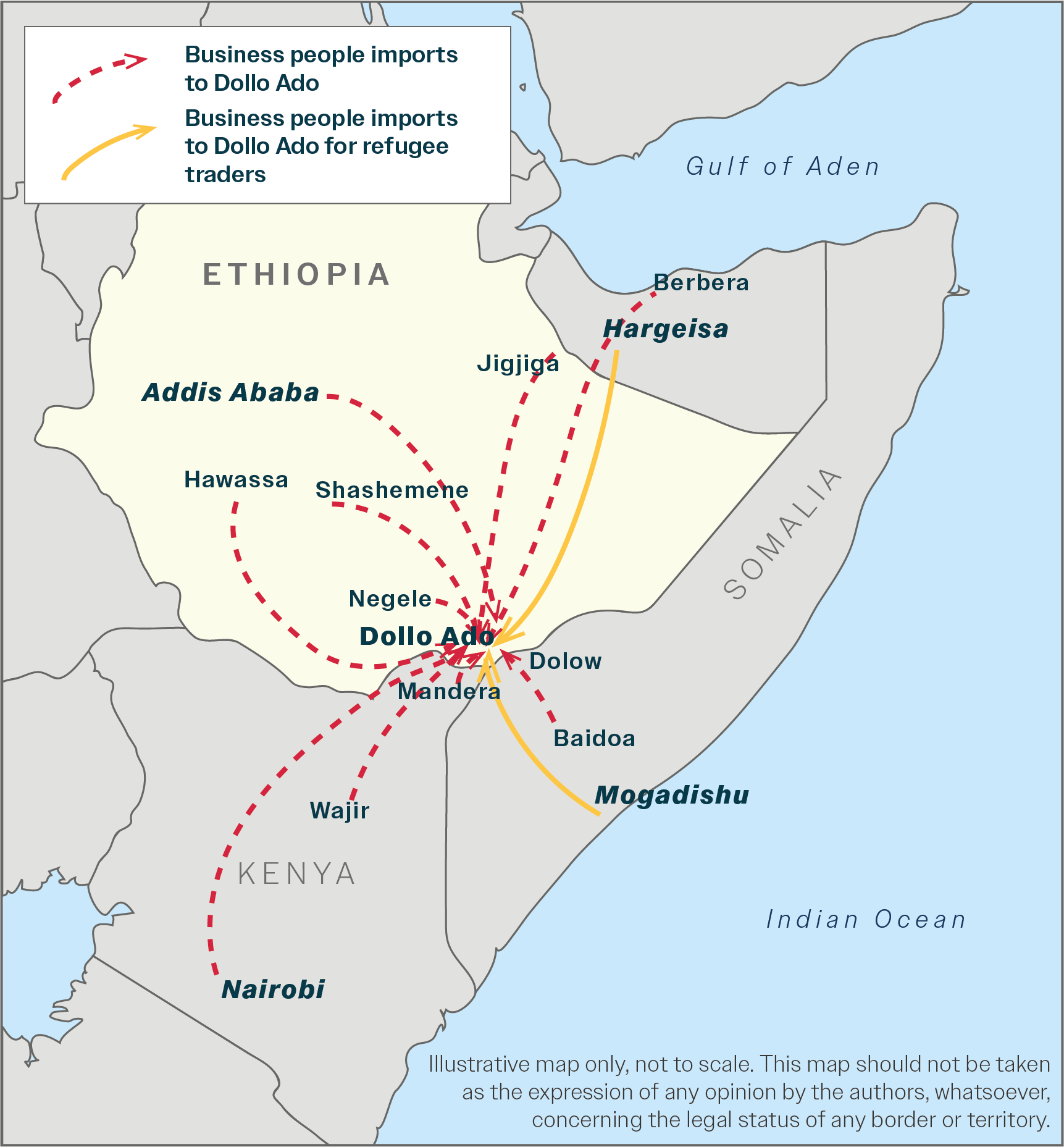

Cross-border activities and informality

The protracted displacement economy among the Somali is supported by cross-border economic activities (Betts et al., 2019). Many displacement-affected communities in Kebribeyah and Dollo Ado complement their livelihoods with cross-border activities. The peripheral economy in the Ethiopia–Somalia border is dominated by informal cross-border trade (Kefale, 2019). This has presented a good opportunity for the displaced communities such as the refugees who neither have the work permits nor the financial capacity to engage in formal trade. While most of the manufactured goods are obtained from the Somalia side of the border, livestock and vegetables are obtained from Ethiopia. The weak state presence in Somalia and the long coastline help to facilitate the supplies of goods (Cassanelli, 2010). The economic activities are based on informal relationships across the border shaped by clan relationships. Women such as Amina, a refugee living with a disability in Kebribeyah, received a small gift of money from relatives in the diaspora. She travelled to Togowjale town on the Somaliland border with several other residents of Kebribeyah. They purchased goods and entrusted them to truck drivers to smuggle them back into Kebribeyah after a few days. In Dollo Ado, businesspeople purchase goods, for instance rice, from one of the major towns of Somalia/Somaliland. Many of the small retail shops in and around the camps take credit from these big businesspeople. The five Dollo camps with a population of over 200,000 and ever-growing towns and villages around the camps offer a big market. Transactions are made by using formal/informal hawala and mobile phone money transfer systems. The borderland offers multiple money transfers: Hello cash and Ebirr (Ethiopia), EVS Plus (Somalia) and M-Pesa (Kenya) operate very well around the border.

Cross-border activities are not limited to trade. They include agricultural works at the place of origin, engaging in paid work, visiting family members and seeking clan support. There are also at least a few people who are registered as IDPs in Somalia so that they can cross the border to collect humanitarian aid (Betts et al., 2019). In July 2023, we observed that many people temporarily fled to Dollow, a town on the Somalia side of the border, either to work in the fields or receive humanitarian support from IDP camps to circumvent the tough situation on the Ethiopian side due to the suspension on food aid. Many of them returned only in November following the resumption of food aid distribution. According to a protection officer in one of the camps in Dollo Ado, usually a quarter of the displaced community cross to Somalia annually to spend over a month there and as a result someone collects their food ration on their behalf.

Sustainability

Here we discuss the formal and informal factors that limit or support engagement in the displacement economy. The displacement economy, especially businesses run by refugees operate wholly outside the formal regulation and taxation system of Ethiopia. The reason is that refugees have highly restricted conditions that would make it virtually impossible to start a business through official channels. These informal mechanisms include trade, transport networks and informal money transfer systems like hawala.

The government has made serious efforts to root out informal money transfer mechanisms because of fears that they are linked to criminal activities. These fears are fuelled by the geopolitics of migration control, as Western countries apply pressure on governments through regional agreements and bilateral arrangements to control different aspects of human smuggling and irregular migration. Their argument is that these activities are operated by criminal syndicates that are also linked to other activities like the trade in drugs and arms. Despite such arguments being poorly evidenced there are growing efforts to crack down on hawala operators. Money transfer operators in the commercial banks situated in the border towns such as Togojale and Moyale were shut down during 2024, making it difficult for the diaspora to send remittances and for business trade with other businesses around the border towns.

Even where refugees are allowed to take up jobs, informal factors like discrimination based on nationality, language and stereotypes of behaviour and character may create barriers, such as the view of Somali men as lazy khat chewers who are not capable of hard work.

The humanitarian anchor

We identified two examples of a humanitarian anchor. First, a project on displacement-affected people’s self-employment and market integration in Kebribeyah and second, the engagement of displacement-affected communities in farming in Dollo Ado.

The project ‘Supporting Socio-economic and Better Employment Opportunities for Refugees and Host Communities Fafan Zone, Somali Region’ is run by two humanitarian organisations, Mercy Corps and Danish Refugee Council (DRC) and funded by the European Union Trust Fund. The project’s aim is to support market growth and ‘create sustainable, lucrative and decent, employment and self-employment opportunities’ for the displacement-affected communities. These two humanitarian organisations invited small businesses owned by ‘refugees’ and ‘host’ communities situated in the displacement-affected areas in and around Jigjiga including Kebribeyah to submit business plans for funding. The funding scheme was set up in a way that the project covers 50% of the cost and the businesses themselves would cover the remaining 50%. The businesses should mobilise 40% of the capital from a diaspora relative or friend. A diaspora member who is willing to become involved in this project has to discuss the business plan with the project management online. Accordingly, 120 businesses were identified towards the end of 2021 and funded based on their 50% contributions.

Mohammed, a young resident of Kebribeyah and university graduate, worked as an enumerator on the PDE baseline survey in 2021. Mohammed has a brother in Australia, and when he heard about this Mercy Corp/DRC project he consulted with his brother who was willing to support him through the scheme. Accordingly, Mohammed managed to be part of the scheme and in February 2022 he opened a stationery shop in Kebribeyah town for 250,000 birr. We visited Mohammed’s shop after over a year of operation in May 2023. The shop had expanded to include photocopying, printing and other services, and he had hired two workers.

The strength of this humanitarian-based project was its engagement with the local context – the role of social factors in economic engagement (Zaman, 2018). In protracted displacement affected areas such as Kebribeyah, as discussed above, the diaspora’s support has been quite strong. However, in most cases, just like the humanitarian organisations, the support of the diaspora was for ‘care and maintenance’. This project innovatively identified a potential opportunity where the agency and aspirations of the displacement-affected communities could be mobilised. The two major outside actors in the livelihood of the displacement-affected community are the humanitarian organisations and the diaspora. This novel approach helped to transform the engagement of the humanitarian organisations and the diaspora from humanitarian to more sustainable livelihood opportunities and economic development of the displacement-affected communities. In addition to the economy, such projects also help the ‘refugees’ to get work permits according to the Ethiopian government’s directives, which have made participation in externally funded projects like this one a requirement to get a work permit.

Dollo Ado has been considered a showcase of displacement-affected communities’ enthusiasm for involvement in development work. The government of Ethiopia’s RRS, UNHCR and IKEA Foundation in 2012 initiated what has been considered ‘the largest private sector investment ever made in a particular refugee setting’ which set out ‘to pilot a new and more sustainable model for refugee response that might ultimately be replicated on a larger scale elsewhere’ (Betts, 2020:9). The project targeted around 2,000 households (half from each ‘refugee’ and ‘host’) organised in agricultural cooperatives. ‘Refugees’ got access to land owned by the ‘host’ and the ‘host’ got access to the irrigation schemes on the Genale River, water pumps, fuel, agricultural inputs and expertise.

Here again our interest is in two fundamental strategies of interventions. First, the intervention took an area-based approach to displacement-affected communities in Dollo Ado rather than only focusing on ‘refugees’. This has taken into consideration the common vulnerability that characterises the displacement-affected community in Dollo Ado, and it has helped to strengthen local economic integration. The impact of the project on displacement-affected populations is much broader and longer-lasting than the targeted households and the reach of the existing irrigation scheme. Many displacement-affected households started a farm using locally available models. Those who had financial capacity to rent land from the ‘host’ community purchased water engines that pump water from the river to the farm, and initiated irrigation. The ‘refugees’’ knowledge of farming compounded by the availability of irrigable land and the irrigation infrastructure put in place by the humanitarian actors introduced new knowledge and technology to the region. Not only the ‘refugees’, but also businessmen and civil servants from Dollo Ado town, the district capital, have rented in land and started farming. Adan is a 45-year-old resident of Buriamino, a small town next to a refugee camp. Adan served in the Ethiopian National Defence Force, and he was deployed to South Sudan as a member of the Ethiopian contingent of the United Nations Mission in South Sudan. Speaking about the impact of the refugees on his life, Adan said:

When they [refugees] produce onions and earn that amount of money… I said to myself, ‘I have to learn’. I cultivated a piece of land… I had a small amount of money from my stay in South Sudan which I used for seed, and other inputs. I produced onions and managed to harvest 350 quintals [a quintal is about 80kg]. I sold 1kg for 18 birr, so fetched over 500,000 birr in total, and bought a pickup car. The car is [popularly] known as the car bought by onions!

The second key design strategy is that those who could not afford to rent land used burjuwas – a sharecropping arrangement common among the Somalis. In this arrangement, the landowner contributes land and the landless contribute labour. The remaining agricultural inputs (such as seed, fertilizer and insecticide) are contributed by both parties. Many ‘refugees’ benefit from burjuwas, as they do not have land or the resources to rent land. The system created the opportunity for the displaced to use their labour and knowledge of agriculture. Many of them engage in farming to produce onions for market and maize for household consumption, and the residue is used for livestock. Regardless of the flood that affected the region in the summer of 2023, when WFP suspended aid distribution for about six months, the advantage of the households who were involved in farming was clear.

In this regard, the humanitarian organisations, a private funder and the Ethiopian government used locally available, but underutilised resources – land, river water and labour – in response to the protracted displacement situation. It contributed to transforming the local economy with an inclusive approach to the entire displacement-affected community, and attracted wealthy businessmen and civil servants who started to benefit from the knowledge and resources created by the displacement.

Conclusion

The Horn of Africa has experienced decades of protracted displacement. Longstanding conflict and recurrent drought have been the major causes of displacement. Ethiopia is currently hosting close to 1 million refugees, mostly from South Sudan, Somalia, Eritrea and Sudan. At the same time, Ethiopia also has over 4 million internally displaced people. This chapter’s primary focus is protracted displacement among the Somali. The Somali’s post-colonial history has been dominated by violent conflict, drought and massive displacement. In Ethiopia Somali ‘refugees’ (those from the Republic of Somalia) are the second biggest refugee population. At the same time, the Somali Regional State of Ethiopia is currently hosting over 1 million IDPs displaced as a result of internal conflict and drought. Many of the inhabitants of the regional state have experienced displacement in their lifetime. Between the 1970s and 1990 most of the inhabitants of the region sought refuge in the Republic of Somalia following the war that took place between Ethiopia and the Republic of Somalia, which was followed by the collapse of the republic of Somalia and caused the displacement of millions of Somali who fled to Ethiopia and Kenya resulting in the displacement-affected communities we have discussed in this chapter. In other words, the ‘hosts’ became ‘refugees’ and the ‘refugees’ became ‘returnees’ and ‘hosts’. In this situation, the boundary between ‘refugee’ and ‘host’ is extremely fluid.

The enduring vulnerability to violence and predicaments of war such as displacement, loss of livelihood, family separation and protracted displacement across the border in Somalia and Ethiopia have created what we have called a displacement-affected community that has shaped the economy of the Somali-inhabited regions. The people not only share a history and an experience of vulnerability, but also ethnicity, religion, cultural practices and psychological makeup that has helped to reinforce the displacement-affected communities’ social cohesion.

In a context of continuing conflict, climate change, displacement and the geo-political periphery of the region, have all caused the informal economy to flourish. In other words, most of the economic activities including those owned by the ‘host’ are run informally – foreign currency is obtained unofficially, goods are imported through informal routes and access to employment is facilitated through unofficial means. This enables the displaced communities, especially ‘refugees’ who do not have work permits, to take part in business informally. Cross-border activities such as informal cross-border mobility for trade and to seek supports from kin across the border are crucially important. Informal businesses across the borders are facilitated by the formal and informal financial systems, such as formal mobile banking and informal hawala.

Local solidarity, support and mutual aid through clan networks play a crucial role in enabling survival and restoring the dignity of displacement-affected communities. Support is in the form of food, money and non-food items. The enduring experiences of displacement and close kinship relationships, as well as similarities in religion and common cultural practices, fostered local solidarity and facilitated support mechanisms. Some of these support mechanisms such as zakat and sadaqa are informed by Islamic religious practices, while others such as shahad emerged as local support practices out of a long history of vulnerability. The supports might be mutual or not and the means of reciprocity might vary. In this situation, the importance of transnational support has been crucial. Besides remitting to their family members and friends, members of the diaspora contribute to support people and projects in their original neighbourhoods and the refugee camps they had once lived in.

Borrowing and taking goods on credit is also an important part of the local solidarity and survival strategy. Many shops in and around refugee camps sell goods, mostly consumable, on credit. Most of the debtors are women, who are the breadwinners of their households, which shows the importance of debt and the feminist economy to the survival and well-being of the household.

Humanitarian organisations have been important in providing care and support to displaced people. They provide a monthly ration, though insufficient, in kind or in the form of cash. Their operations have continued to be largely a response to the emergency situation and the transition to locally sustainable development has remained slow. In this chapter, we discussed two initiatives in Dollo Ado and Kebribeyah where humanitarian organisations engaged in locally anchored and sustainable development. The major strength of both initiatives is their inclusiveness and an area-based approach where all displacement-affected communities participated and developed locally available and potentially sustainable resources. Identifying available opportunity structures, such as the locally available natural resources, local and cross-border trades, local and global networks, and creating an enabling environment, including support with finance, would support the transition from ‘care and maintenance’ to a sustainable economy for displacement-affected communities.

References

Betts, A., Bradenbrink, R., Greenland, J., Omata, N., & Sterck, O. (2019). Refugee Economies in Dollo Ado: Development Opportunities in a Border Region of Ethiopia. Oxford, Refugee Study Centre. https://www.rsc.ox.ac.uk/publications/refugee-economies-in-dollo-ado-development-opportunities-in-a-border-region-of-ethiopia

Betts, A., Marden, A., Bradenbrink, R., & Kaufman, J. (2020). Building Refugee Economies: An evaluation of the IKEA Foundation’s programmes in Dollo Ado. Oxford, UK: Refugee Study Centre. https://www.rsc.ox.ac.uk/publications/building-refugee-economies-an-evaluation-of-the-ikea-foundations-programmes-in-dollo-ado

Carver, F., Ahmed, A. G., & Naish, D. (2020). Somali regional report: 2018–2019 refugee and host community context analysis. https://media.odi.org/documents/somali_regional_report_2018-2019_refugee_and_host_community_context_analysis.pdf

Cassanelli, L. (2010). The Opportunistic economies of the Kenyan-Somali borderlands in Historical Perspectives, in Dereje, F. & Hoehne, M. (Eds.) Borders and Borderlands as Resources in The Horn of Africa. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell and Brewer.

Gallien, M., Javed, U., & Boogaard, V. Z. (2023). Non-State Welfare Provision and Redistribution in Times of Crisis: Evidence from the Covid-19 Pandemic: ICTD Working Paper 163. DOI: 10.19088/ICTD.2023.037

Hammond, L. (2014). History, Overview, Trends and Issues in Major Somali Refugee Displacements in the Near Region (Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda and Yemen), Bildhaan: An International Journal of Somali Studies, (13)7, 55–79.

Ikanda, F. (2025). Remittances and kinship obligations in the era of Covid-19: Case of Somali refugees at the Dagahaley camp in Kenya, in Owiso, M.O., Tufa, F.A. & Hersi, A.M. (Eds.), Migration and Displacement in the IGAD Region: Human Mobility in the Context of COVID-19. Singapore: Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-97-6611-6_12

Kefale, A. (2019). Shoats and smart phones: Cross-border trading in the Ethio-Somaliland corridor. Working Paper No. 2019:7. Copenhagen, Denmark: Danish Institute for International Studies. https://hdl.handle.net/10419/204632

Lewis, I. M. (2002). A modern history of the Somali: nation and state in the Horn of Africa. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell and Brewer, James Currey. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv136c1w2

Lyberaki, A. (2011). Migrant Women, Care Work, and Women’s Employment in Greece, Feminist Economics, 17(3), 103–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2011.583201

Olmsted, J. (1997). Telling Palestinian women’s economic stories, Feminist Economics, 3(2), 141–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/135457097338771

UNHCR. (2025). Ethiopia: country fact sheet, January 2025. Operational Data Portal. https://data.unhcr.org/en/country/eth

Van Brabant, K. (1994). Bad borders make bad neighbours: the political economy of relief and rehabilitation in the Somali Region 5, Eastern Ethiopia. Humanitarian Practice Network. https://odihpn.org/publication/bad-borders-make-bad-neighbours-the-political-economy-of-relief-and-rehabilitation-in-the-somali-region-5-eastern-ethiopia

Zaman, T. (2018). The ‘humanitarian anchor’: A social economy approach to assistance in protracted displacement situations. Humanitarian Policy Group.

- In 2023, two additional refugee camps were established at Mirqaan and Bokh hosting over 90,000 people who there fled when the war broke out at Laascaanood between the Somali national army supported by clan militia and the Somaliland army. ↵

Money transfer system.

Prosperity.

A handout to a person who is familiar or a distant friend.

Autorickshaw.

Prayer.

A form of giving/taking in a context of vulnerability.

A form of charitable giving, a fundamental pillar of the Islamic faith and an obligation for all those able to give.

A sharecropping arrangement common among the Somalis (Ethiopia).

A handout to a person who is familiar or a distant friend.