5 Lebanon

Tahir Zaman; Claude Samaha; and Rouba Mhaissen

Country context

Syria and Lebanon have historically been deeply intertwined with one another and the two countries and their peoples have had a close, if not always cordial, relationship even prior to each country’s creation. The 2011 Syrian conflict had fundamental and complex transformational effects on Lebanese society, politics and economic conditions.

At the start of the conflict, many refugees escaped to Lebanon and according to the most recent UNHCR figures, today there are 755,426 registered Syrian refugees and approximately an equal number of undocumented Syrians living in Lebanon. This officially constitutes over a third of the country’s population, and has put a strain on both host and refugee communities in the country. Additionally, since 2011, and especially since 2019, Lebanon has faced a host of security and economic crises, including the rapid inflation and devaluation of the Lebanese currency that left the majority of Lebanese below the global poverty line.

Lebanon is not a signatory to the 1951 Geneva Convention or its 1967 Protocol relating to the status of refugees. Syrian refugees in Lebanon, therefore, do not have formal refugee status but are ‘displaced persons’ facing severe legal restrictions on their ability to work, move around and pursue their livelihoods. Many Syrians lack access to basic services such as electricity, water, housing, healthcare, education and employment. The situation is particularly difficult for vulnerable populations, including women, children and the elderly. This has driven refugees to find informal and ad hoc solutions to fulfil their needs, resulting in limited and inadequate access to basic services.

As a result of the combination of legal discrimination against Syrians, the existing and steadily declining economic and political conditions in Lebanon, and the sheer number of new people in the country, tensions between Syrians and Lebanese people living in Lebanon are also quite high. In many sectors, refugees and the host population must compete over limited resources which increases feelings of resentment and creates strained relations between host and refugee communities.

For example, in the labour market Syrian refugees have been put in direct competition with the most vulnerable Lebanese workers as a result of government policy restricting Syrian to labour-intensive low-paying jobs and the failing Lebanese economy. In the existing context of the very high unemployment rate in Lebanon, this has led to resentment within the host community. Various international organisations, NGOs and host communities are working to provide assistance and support to alleviate the hardships faced by Syrian refugees. However, the scale of the crisis and the limited resources available pose ongoing challenges to meeting the needs of the refugee population.

International research collaborations often involve partners from academic institutions in the country where research is being undertaken. In the case of Lebanon, we decided to partner with two grassroots refugee-led NGOs that were embedded in the displacement-affected localities we had selected as research sites. This was made possible as both NGOs, Basmeh & Zeitooneh and SAWA for Development & Aid, had broadened their activities beyond providing assistance to displacement-affected communities in Lebanon. In recent years they had also established policy and research departments at their organisations in an effort to take ownership over the direction in which research on Syrian displacement was unfolding.

Research challenges in Lebanon

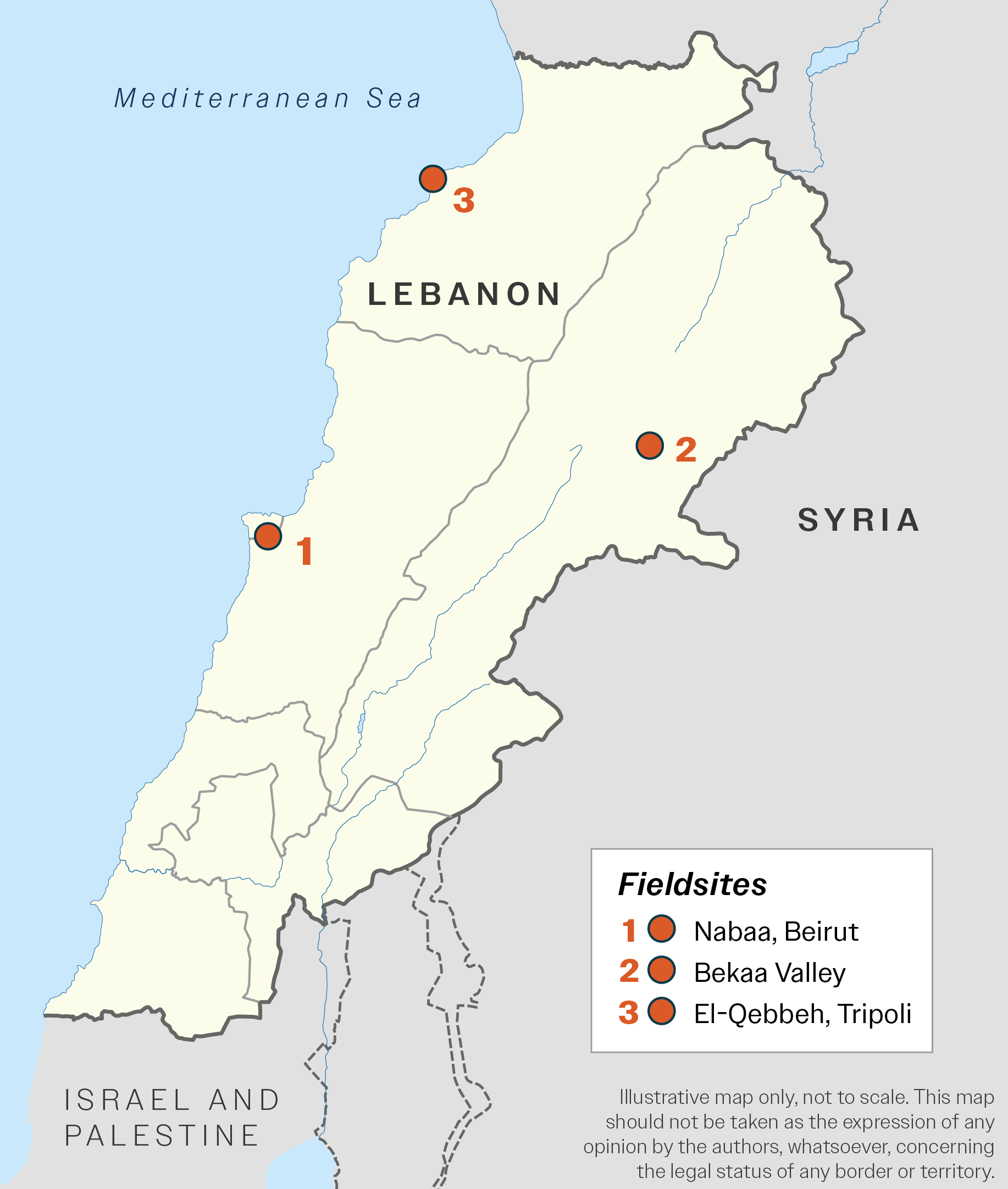

This project explores the economic and social dynamics of refugee populations in Lebanon, focusing on three research locations: El-Qebbeh in Tripoli, Nabaa in Beirut, and Bar Elias in the Bekaa Valley. The research highlights the challenges faced by both Syrian refugees and the host communities, examines the impact on the labour market, and sheds light on the demographic changes in the research locations.

The actual data collection process had to be carefully planned and we faced several challenges that we had to account for during the research design phase that provide important lessons for future research conducted in such situations. The two main challenges came from the fact that data collection took place during the Covid-19 pandemic and that the political and economic situation in Lebanon was highly uncertain and rapidly changing. We therefore had to accommodate these in our research design.

Research challenges due to Covid-19

Given the circumstances of the Covid-19 pandemic, conducting research presented a range of challenges encompassing safety, ethics and practical considerations.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, ensuring safety became a key priority, with a focus on managing health risks in accordance with established public health guidelines. Our primary concern was to address the well-being of all individuals involved, including both participants and researchers. Establishing explicit protocols for conducting research during this challenging time was crucial. We took the concerns of participants and enumerators regarding potential exposure and transmission of Covid-19 seriously and ensured they were appropriately addressed.

Obtaining necessary permissions from local authorities was a prerequisite. Effective and transparent communication among various stakeholders, including law enforcement, research organisers, local enumerators and participants, played a pivotal role in addressing safety concerns and mitigating risks. Therefore, it was crucial to establish a robust risk management process that incorporated input from all stakeholders and enabled the identification of acceptable levels of risk and their potential sources.

Despite the challenges, our research team successfully conducted the baseline survey in person, using a door-to-door method. The survey collection was aligned with best practices in public health, which included implementing measures like mask wearing, practising social distancing and following rigorous testing protocols. Although these measures incurred additional costs, they ensured the safety and well-being of both our workforce and participants.

The Covid-19 pandemic presented unique ethical challenges, particularly in conducting one-on-one interviews. We deliberated internally about the option of conducting these interviews electronically, taking into account various limitations. We recognised the potential risk of inadvertently reinforcing inequalities and marginalising certain groups through such electronic research activities. Factors such as limited digital literacy, lack of access to technology and practical constraints made it challenging to effectively engage and include these populations. Moreover, we recognised that conducting interviews electronically may have potentially impeded the establishment of a genuine human connection that typically occurs during in-person interviews. This lack of face-to-face interaction and nonverbal cues could have influenced the quality and depth of the interviews, as the personal rapport between the interviewer and the participant might not have developed as naturally or strongly. As a result, the decision was made to temporarily suspend the interviews until further notice while closely monitoring the situation.

Additional research challenges in Lebanon

Regardless of the time frame, conducting research in Lebanon presents persistent challenges due to the country’s regular political instability, street protests, sporadic armed conflicts and occasional tensions with neighbouring nations. During the PDE research carried out in Lebanon, the country has grappled with three major crises of immense magnitude, leaving indelible impacts not only on Lebanon but also resonating globally. These crises include the Covid-19 pandemic, the devastating Beirut blast, which was recognised as the third-largest non-nuclear explosion in history, and the most severe economic crisis witnessed in the past decade. Furthermore, during the final phase of the project, a state-led deportation campaign targeting Syrian refugees further compounded the challenges faced by the research team.

During the period of data gathering, the country was also going through a dire economic downturn accompanied by a worsening security situation. Lebanon’s economy is highly dependent on imports, and residents have long depended on a regular influx of US dollars. The official exchange rate had been fixed at 1,507.5 Lebanese pounds (LBP) to US$1 since 1997. By March 2021, however, the LBP had depreciated to the extent that the unofficial exchange rate hit 15,000 LBP to US$1. The World Bank has described the precipitous collapse of the Lebanese economy as one of the worst ever recorded since the mid-nineteenth century (World Bank, 2021).

The impact of multiple crises has been pronounced. Considering factors other than income, such as access to health, education and public utilities, 82% of the population in Lebanon lives in multidimensional poverty (UNESCWA, 2021). A UNICEF report in March 2021 found that 77% of 1,244 households surveyed indicated that they did not have enough food or enough money to purchase food. For Syrian households, this figure rose to 99% (ibid.). Worsening opportunities for informal employment have escalated debt accumulation for Syrian refugees with 93% borrowing for food, 48% for rent and 34% for medicine (Karasapan & Shah, 2021). The depletion of currency reserves has increased the likelihood of the Lebanese Central Bank cutting its subsidy programme on which much of the population has been reliant. This context of overlapping crises made it particularly challenging to plan and carry out research activities.

The financial situation in Lebanon also meant that there were limited resources available for research, including access to specialised equipment. The research infrastructure in the country is limited and centralised in the capital where the major universities are located. The quality of available data on Lebanon can be outdated and incomplete, requiring researchers to invest additional effort in data collection and validation. The financial crisis also accentuates the differences between participants and researchers in terms of access to economic resources.

We also needed to consider the safety of participants themselves when in the country. During periods of heightened tension, some regions cannot be accessed at all. Furthermore, research with vulnerable populations like refugees requires extra steps to ensure the safety and confidentiality of participants. Creative and locally appropriate solutions for informed consent and identity protection are necessary to conduct research ethically. Refugees and marginalised populations also live in remote and difficult-to-access areas.

All of these challenges require researchers to be flexible, resourceful and sensitive to the local context. There are important opportunities for capacity building, knowledge exchange and improving research practices if the research design is well thought out. In this context, the project developed strong partnerships with local organisations and relevant stakeholders by engaging in community-based research and adapting research methodologies to fit the Lebanese context . Additionally, through collaboration with local researchers and institutions research sought to be beneficial for navigating challenges and accessing resources.

The research process

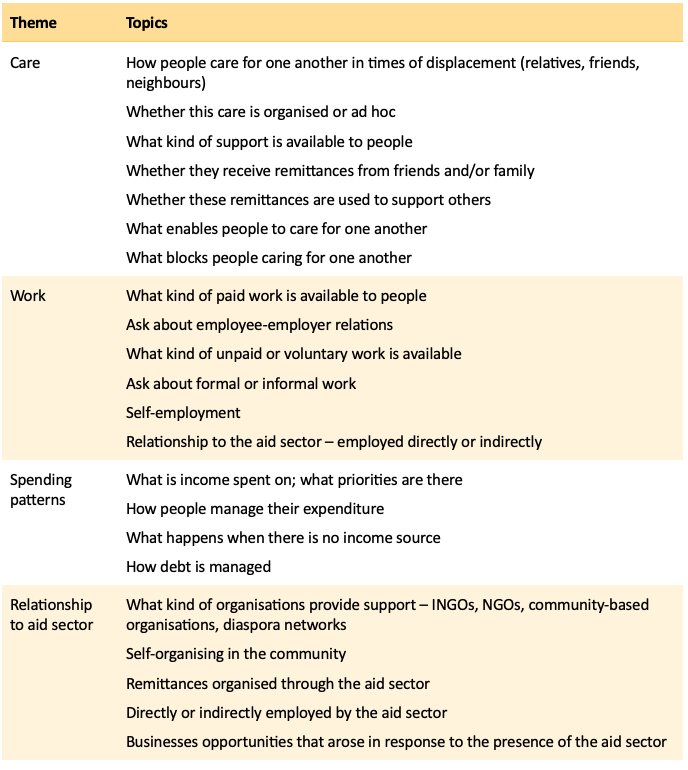

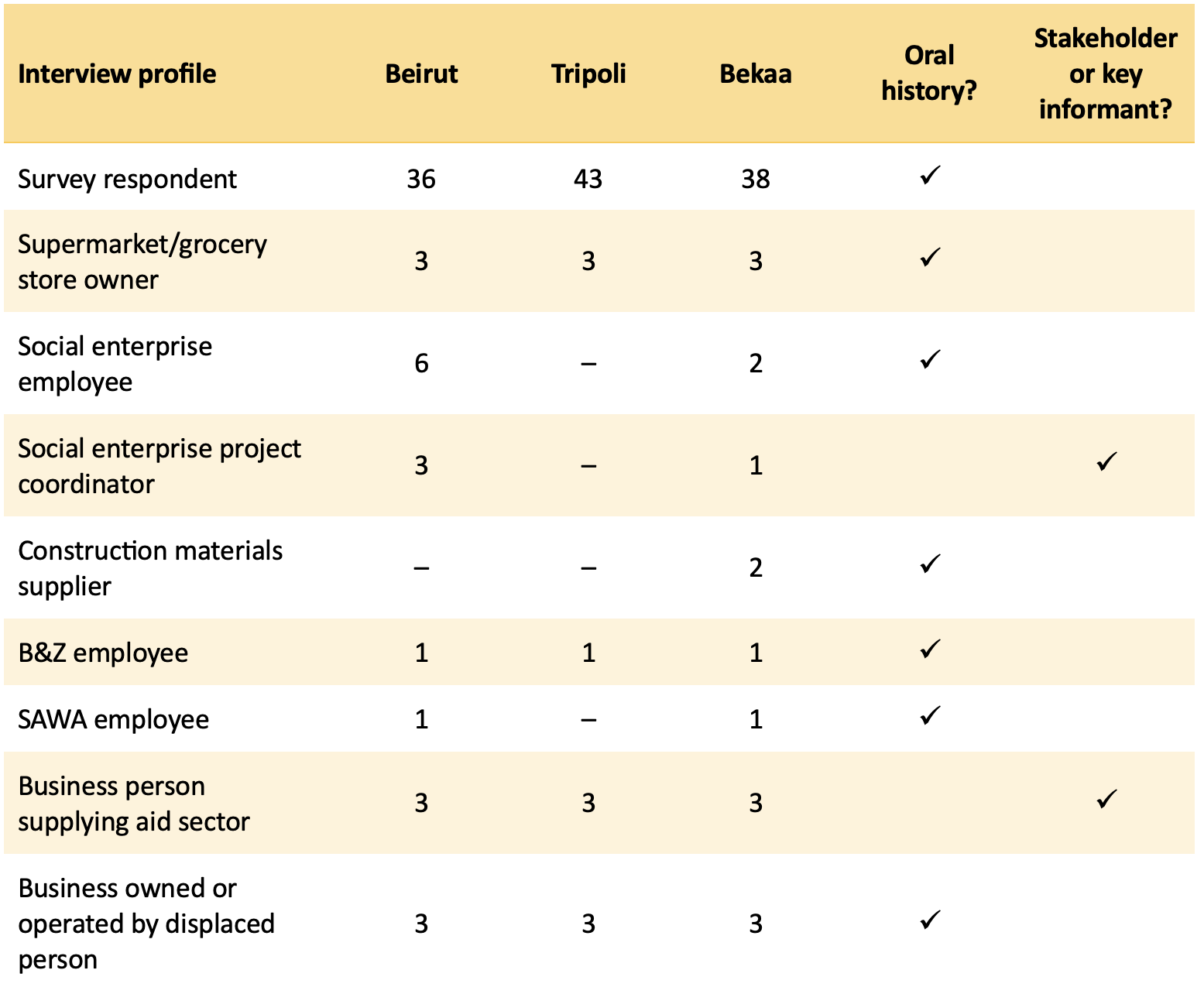

This longitudinal research project was designed to span a duration of three years, allowing for a comprehensive and in-depth understanding of the research topic. To ensure a holistic approach, three distinct data-gathering methods were employed: focus group discussions, surveys and qualitative oral history interviews. The focus group discussions involved key informants and stakeholders, providing valuable insights into the prevailing conditions at the research sites. Surveys were administered in two rounds, covering a wide range of topics such as demographics, economic household situations and aid mechanisms. Qualitative oral history interviews captured personal narratives and individual perspectives, offering rich insights into the lived experiences of the participants.

The research project began with careful selection of individuals possessing relevant professional experience and expertise related to the specific sites and sectors under investigation. Focus groups were then established, engaging participants identified through community organisations to shape the initial survey questionnaire. Feedback from these consultations played a crucial role in designing the first questionnaire. Enumerators underwent comprehensive training to administer and apply the questionnaire effectively. Individual qualitative oral history interviews were conducted, followed by two more rounds of interviews with a panel of selected participants. Enumerators simultaneously carried out the second round of surveys involving 20% of the baseline participants. The collected data is currently undergoing cleaning and validation before being analysed. The findings will be visually presented on a dashboard and shared with the research team. Additionally, a final round of focus group discussions will be conducted to further enhance the understanding of the research outcomes.

Throughout the research process, participants were well-informed about their rights and the concept of informed consent. Questions focused primarily on non-financial economic activities, and participants had the right to withdraw from the research at any time without forfeiting incentives. Contact information was provided for participants to withdraw their consent if desired. Identifying data collected was securely stored and protected to ensure confidentiality.

Conducting research with research-led organisations (RLOs) in Lebanon presents specific challenges due to the legal and administrative frameworks. Compliance with regulations and ethical standards is paramount to maintain integrity. Enumerators underwent comprehensive training covering research skills, ethical standards and participant protection, including topics such as prevention of sexual exploitation and abuse, child protection and adherence to a code of conduct. In addition, we were faced with the challenge of retaining Lebanese national researchers. The deteriorating economic situation in Lebanon compelled many to take opportunities outside the country as they arose.

The effectiveness of the training varied among interviewees, with factors such as the enumerators’ background and nationality impacting the quality of interviews. Those with medical expertise or strong listening skills forged stronger connections. However, challenges arose when nationality differences hindered cooperation. To address this, we prioritised recruiting refugees from the community itself. Cultural norms in Lebanon also influenced the expression of emotion during interviews.

These dynamics highlight the complexity of fieldwork and the importance of promoting open communication, understanding cultural nuances, and ensuring a safe and inclusive environment for participants.

Site selection and community profiles

In order to fully capture the diversity of lived experiences of refugees in particular and the displacement affected communities more generally, we decided to conduct research in three locations. The first was in Nabaa, a suburb of Lebanon’s capital Beirut, known for its diverse population and for having hosted Palestinian refugees since 1948. It is an urban setting, characterised by widespread lack of regulation in relation to housing and the labour market. The second is in El-Qebbeh in Tripoli, north Lebanon, which has been known to be receptive to Syrian refugees but where those already resident were highly vulnerable themselves. The third was in Bar Elias, a town on the Syrian border with a very high percentage of its population made up of refugees. The outskirts of Bar Elias where many Syrians are resident can best be described as peri-urban. The diversity of these locations, from urban to rural, with refugees living in both houses and camps, significantly affects the nature of the livelihoods (both formal and informal) of refugee populations, and the relationships they form amongst themselves and with the wider displacement-affected community.

El-Qebbeh in Tripoli serves as an immediate and relatively accessible refuge for Syrians escaping the war in Syria. The area hosts a significant number of Syrian refugees, accounting for approximately one-third of all registered Syrian refugees in Lebanon. As with neighbourhoods in Beirut (Fawaz, 2017) and Halba (Fawaz et al., 2022), the majority of displaced Syrians in El-Qebbeh find housing in private accommodation or with relatives in small towns in the region. Informal camp settlements supported by local NGOs are also prevalent, with the Bekaa region hosting the majority of these settlements.

Nabaa, a suburb of Beirut, is characterised by a diverse population consisting of Lebanese, Syrian, Palestinian and Iraqi refugees, and foreign migrant workers from African and Asian countries. The majority of the population comprises refugees, particularly Syrians. The area has experienced significant demographic changes as a result of the Lebanese Civil War and the influx of Syrian refugees since 2011. Tensions arise from cultural differences and diversity, sometimes escalating into fights. The economic activities in Nabaa are mainly focused on wholesale and retail trade, with various types of shops dominating the neighbourhood’s economic landscape.

Bar Elias, located in the Bekaa Valley, has a historical connection with Syria in terms of trade and experienced labour migration from Syria prior to the conflict. Since the outbreak of the conflict in 2011, Bar Elias has witnessed a disproportionate influx of Syrian refugees. The Bekaa Valley, as a whole, has received the highest number of Syrian refugees in Lebanon and hosts the largest concentration of informal settlements (Sanyal, 2017; Sajadian, 2024; Nassar, 2025). The population of Bar Elias has increased by 50% since 2011, presenting challenges in terms of employment opportunities and strained resources.

Quantitative methods – baseline and panel surveys

Designing a survey to understand the refugee situation in five countries simultaneously (the DRC, Ethiopia, Pakistan, Myanmar and Lebanon) while using the same set of questions, posed a significant challenge. The nature of this approach resulted in a lengthy survey that encompassed many questions that were not necessarily relevant to the Lebanese context. However, one of the primary goals of the research was to enable a comparative analysis that would ultimately yield valuable insights. The value of conducting such a comparative study outweighed the difficulties encountered during the implementation phase.

Once the survey design was completed, we created teams of about 12 people to carry out the survey at each site. Enumerators were given an induction session to introduce the project and its objectives and three training sessions on the questionnaires and Kobo software. To familiarise the team with the questionnaire and anticipate participant queries, multiple survey collection trials were conducted. These trials refined the survey process and equipped the team to effectively address participant concerns. To prioritise data protection and uphold ethical standards, tablet devices used in the research project were designed to facilitate the collection of verbal informed consent. In hindsight, we have identified areas for improvement in our approach. One important aspect was the need for enumerators to inform centre coordinators about their presence in the field to enhance security measures. Conducting data collection during official working hours proved advantageous, as it ensured immediate support and assistance when needed. Enumerators need to be provided with power banks and water bottles and they need to be able to use Kobo without an internet connection. Gender diversity within enumerator teams proved beneficial for data collection, emphasising the importance of including both genders in the groups. Regular weekly meetings held at community centres fostered communication and collaboration among stakeholders, providing a platform for progress updates, addressing challenges, and ensuring alignment with project objectives. The use of WhatsApp as a dedicated communication channel facilitated real-time information sharing between the core and regional teams.

To implement a randomised sampling approach, the research team divided each region into zones based on random sampling of neighbourhoods. Gender representation was also balanced across the zones to enhance inclusivity and diversity.

The research focused on community centres run by Basmeh & Zeitooneh and their surroundings as primary data collection sites. Conducting research in these familiar spaces created a comfortable environment for open participation. Collaborative efforts between community centres and research team were made to offer incentives that encouraged participation without creating a perception of bribery. This collaborative approach strengthened the research’s credibility and fostered a sense of ownership and partnership with the community centres, ultimately enhancing the study’s overall quality and impact.

The implementation of the surveying process faced significant challenges, primarily stemming from the difficult socioeconomic conditions in the survey sites. Frequent electricity and internet outages, as well as fuel shortages, hindered the data collection efforts. Some individuals were hesitant to participate, while others outright declined to take part in the questionnaire. The questionnaire itself presented difficulties for participants, with concerns raised about its length, particularly when multiple family members were present. Moreover, certain questions elicited discomfort among participants, leading to hesitancy in providing responses. These challenges highlight the complex nature of conducting surveys in such challenging contexts. Despite these obstacles, in July 2020, we successfully gathered a total of 4,502 surveys from all designated regions in Lebanon.

Cleaning and validating the collected data posed challenges for the regional supervisors, who played a crucial role in ensuring the accuracy and relevance of the findings. Throughout the survey, supervisors closely monitored the survey count and verified questionnaire submissions. However, during the analysis phase, several issues emerged.

One commonly encountered problem was the registering of phone numbers containing additional digits. A further, more complex problem can be attributed to the financial crisis Lebanon was mired in. Rapidly fluctuating exchange rates meant it was difficult to keep track of incomes and expenditures. To address this issue, the analysis team was consulted and a decision was made to randomly select around 5% of the baseline data as the panel. Direct calls were then made to verify phone numbers and resolve any discrepancies related to currency differences. Employing inductive inference, all the collected data was adjusted based on the information obtained, ensuring accuracy in the final analysis. With extensive experience and ample resources, we embarked on the data collection for the second round of surveys in June 2023. Originally planned for March 2023, the survey was rescheduled owing to security concerns arising from escalating discrimination and a concerted deportation campaign targeting Syrians (Kheshen, 2024). Our panel consisted of 600 participants, accounting for around 14% of the baseline sample. The survey utilised the same set of questions as the previous round, with additional inquiries pertaining to the documentation status of our panel members.

While our skilled enumerators encountered minimal challenges during the actual survey process, the dynamic circumstances and security issues posed obstacles. Enumerators had to contact participants using self-provided phone numbers obtained during the baseline survey, inviting them to complete the survey at designated centres and providing transportation fees.

However, various issues surfaced during the process. Many phone numbers had become invalid or had been reassigned to different individuals. Some participants had relocated to areas where municipalities or host communities exhibited more flexibility towards refugees. Additionally, some participants mistook our survey for the one conducted by the Lebanese authorities for Syrian refugees, leading to their refusal to participate. Furthermore, despite confirming their attendance, some participants failed to show up for the scheduled survey sessions. Despite these challenges, we successfully completed the survey in all three regions.

Qualitative interviews

The PDE research project employed an innovative approach of conducting open-ended oral history interviews, alongside the film-making component. This method provided a unique platform for refugees to share their experiences and perspectives in their own words. However, it required specific qualifications and skills from the interviewers, who initially lacked the necessary expertise.

To address this challenge, the interviewers underwent two comprehensive training sessions. The first session, conducted remotely by the experienced core research team, familiarised the interviewers with techniques and guidelines for effective oral history interviews. The second session, held in person, provided an opportunity for the interviewers to practise their skills and simulate interview scenarios under the guidance of experienced team members. This investment in their professional development aimed to ensure the interviewers were well-prepared to elicit rich narratives and perspectives from the participants, thereby enhancing the overall quality of the research findings.

The initial round of interviews took place from March 2022 to July 2023. During this phase, the interviewers faced challenges owing to their limited familiarity with the interview process, resulting in some interviews lacking essential information. To address this, follow-up sessions were conducted with each interviewer individually, providing an opportunity to review their work, discuss challenges and collectively determine the best approaches for effective interviews.

The nationality and qualifications of the interviewers played a significant role in shaping the interviews. Their diverse backgrounds and expertise brought different perspectives and skills, influencing the depth and richness of the collected information. Additionally, the willingness of the participants to share their experiences and information also contributed to the success of the interviews. Throughout the initial round, all contacted individuals agreed to participate, despite initial reservations expressed by some. As the interviews progressed, participants displayed enjoyment and enthusiasm in sharing their stories, indicating the positive impact of being listened to and of recounting their experiences. By the end of the initial round, 150 interviews had been conducted across the three selected regions, ensuring gender equality and balanced representation within each region. Out of these interviews, 128 were conducted with individuals from the baseline cohort, while 22 participants resided in the same areas where the initial baseline was established.

In the second round, held in January 2023, a total of 90 interviewees from the first round were invited to participate. Although already familiar with the purpose of the interviews, participants found themselves reflecting on what they had previously shared during the initial round. Despite the absence of two interviewers, the remaining team successfully conducted the interviews, resulting in improved quality compared to the first round.

For the third round, 10 interviews were carefully selected from the pool of 90 interviews conducted in the second round. This round coincided with an arrest campaign targeting undocumented Syrians in Lebanon, leading to resistance from some participants. Nonetheless, five interviews were successfully conducted in May 2023, exhibiting exceptional execution and providing valuable insights.

Overall, the utilisation of open-ended oral history interviews proved to be a fruitful method for capturing the experiences and perspectives of the refugee population. The comprehensive training, follow-up sessions, and diversity of interviewers contributed to the success of the interviews, despite challenges faced throughout the process.

Production of documentary films

Stories without Borders: Lebanon workshop

Under the umbrella of ‘Stories without Borders: Displacement Economies’, these short documentary films were made by young filmmakers across our five research locations. In an intensive 10-day, hands-on filmmaking workshop, the filmmakers developed, produced and edited their films. The results are playful, thoughtful and unexpected reflections on the themes of the Protracted Displacement Economies research project, including: the care economy; sharing; mutual aid; informal support systems; monetary and non-monetary aid systems; employment (or lack thereof); and the role and perception of community-based organisations in communities that have witnessed several waves of displacement and migration. The workshop was held at the Basmeh & Zeitooneh Community Centre in Bourj Hammoud between 28 Februrary and 9 March 2022. The workshop was convened by Yasmin Fedda and supported by Tahir Zaman. Claude Samaha acted in the capacity of coordinator. Over 60 applicants applied to the open call for the workshop. The call out stated that this was for filmmakers early in their careers, or who may have had some experience working in film. The majority of applicants were Syrians, with some Palestinians, many of whom had had some exposure to filmmaking. Among the participants that applied from the Bekaa region, a number had strong filmmaking experience since they had attended the Action for Hope film school there. They also had good technical skills, but none had worked in documentary filmmaking before. Other participants had a mixture of some basic experience working on fiction films, reportage or campaigning films. There were no Lebanese applicants.

Of the participants we selected, all seemed to want to take part because they wanted more filmmaking experience. This may be attributed in part to a lack of educational access or, if they were enrolled at a university (the case of one participant), because their university did not offer such courses or experience. Experience was distributed unevenly within the whole group – as mentioned above, the Bekaa cohort had had some training, while others had had much less. For example, all the female participants in the workshop had worked in either campaigning or reportage. While they had not necessarily gained any filming or editing skills in these roles, they had a rudimentary understanding of what such skills entailed, having been part of the process. To ensure effective teamwork, each team comprised members who could demonstrate a range of skills – from camera and filming experience, editing, or producing and finding stories.

In the workshop they were given technical training on how to use the camera and sound equipment. They were also encouraged to plan and plot a narrative arc to their films. The workshops helped them consider how decision making in the filming process can prompt emotion in the viewer. They were encouraged to consider the variety of shots possible when filming, to think about how a scene comes together and the images required to successfully edit those scenes, and how best to record sound in different kinds of scenarios – for example, on a street or for an interview. We began the workshop with the PDE team giving the participants the headline objectives of the broader research project in order to encourage them to think of ideas within those to develop. The themes of the project resonated with the lived experiences of the participants allowing them to grasp the conceptual underpinning of PDE easily.

On the first day of the workshop participants were exposed to the many approaches to making creative documentary, and to consider different forms and objects. The aim of this was to show the many creative possibilities open to them, rather than understanding documentary as news reportage. They then pitched ideas they understood as best reflecting the thematic focus of the PDE project but through their networks and lived experiences.

On the second day they pitched their ideas for their films. They were all encouraged to share an idea and then the organising team discussed the ideas and what was most feasible to make in the short timeframe of the workshop. We asked questions about each idea related to access, logistics and the approach of the filmmakers.

The team from Bekaa was constrained by only being able to film in Beirut and its surrounding area, though all their contacts were in Bekaa. They did suggest some ideas but these were ultimately not feasible because of the access and approach required. Another team proposed shooting a short observational documentary with an elderly neighbour of one of the participants. However, consent from her family members was not forthcoming at such short notice – indicating the limitation of the very short timeframe of 10 days in which the workshops were convened.

It is interesting to note that all the ideas proposed by the participants came from their experiences or networks, for example, thinking of people they knew who worked in the aid sector, their neighbours whom they supported, or how people have created their own businesses to survive.

We chose three ideas for development and filming. The first followed the daily life of young boys collecting plastic in Shatila Camp, Beirut. This idea was developed through encouragement to think about the process of recycling, and not only the boy’s stories. This decision meant the group did not film interviews with the boys. Access to this story was made possible by a participant who lived in Shatila and saw these boys on a daily basis. Her brother bought plastic from them which was then sold to an NGO that operated an industrial plant recycling the plastic. The film captured the intricate ways in which informal livelihoods entwine with formal development interventions to produce place-based economies.

Cycles

A film by Anas Al Sheik, Nisreen Hazineh and Shawki Al Hallak

We have fallen and are trying to stand. We keep on going. The world keeps spinning and we spin along with it in search for our daily bread in the current economic situation. We have become like the pieces of plastic recycled and refined, we are spinning to find a better reality.

9:04 mins; Arabic with English subtitles, 2022.

The second film was an observational piece documenting a day in grocery shop in Saida. The grocery shop was run by a Syrian family, the family of one of our participants. His love of hip hop allowed him to convince his father to set up a music studio above the shop. We encouraged the filmmakers to make the film about the father and son’s relationship and what it means to pursue dreams in the context of displacement.

Cornershop Beats

A film by: Bassam al Khaled; Abdul Malik Al Ali; Saja Awad

In a family run grocery shop in Saida (south Lebanon), a father and son try to make their dreams come true.

7:47 mins; Arabic with English subtitles Arabic dialogue with English subtitles, 2022

The third and final film was originally meant to be about mutual aid and how one of the filmmakers supported his elderly neighbour. However, lack of access hindered the possibility of following that particular story. The filmmakers ended up filming it as an experimental vox pop asking strangers about what neighbourliness means. The impromptu interviews were conducted in Burj Hammoud, a neighbourhood adjoining Nabaa that is home to not only working-class Arab Lebanese and Syrian refugees, but also a longstanding Armenian community and an array of migrants from Eritrea, Ethiopia, the Philippines and Bangladesh to name a few. It became clear that many migrants from East Africa or South Asia on wakil (sponsored) visas were not keen to be filmed, so in the end the film was made up of Lebanese, Syrian and Armenian participants and not so much from other nationalities living in the same neighbourhood.

Neighbourhood of Creatures

A film by: Kareem Nofal; Raneen Alomar; Adnan Alghati

A reflective, unexpected documentary film made up of vox pops on the streets of Bourj Hamoud and Al Dawra in Beirut – asking passersby what it means to belong.

5:43 mins; Arabic with English subtitles, 2022.

The participants were very keen and eager to learn and brought their personal experiences to the workshop, which fed into the development of the film ideas. It was great to see how their ideas developed over the few intense days they spent together, going from the seed of an idea to a more developed film. At the public screening it was moving to hear what the films meant to the filmmakers, and how much more personal they were than expected; even when the film was not about them per se, the subjects were close to their hearts. Reflecting on the process, the Lebanon team felt that the filmmaking workshops should have preceded any other data gathering we did. The workshops provided an opportunity to delve deeply into what living and experiencing protracted displacement means in the economic lives of displacement-affected people. If sequenced during the first phase of research, the film workshops would have provided a grounded base from which to think about the design of other quantitative and qualitative tools.

Stakeholder engagement

As part of our research design, we identified stakeholders as particularly important members of the community who could give us greater insight into the local economic dynamics in a country with high social tensions between the local community and the displaced population. Involving those stakeholders early on in the project was an important step to ensure their inclusivity in the process as a whole, and that their opinions, concerns and hopes about a healthier relationship between refugees and their host country would be included. To that end, we conducted throughout the project two rounds of stakeholder interviews with heads of municipalities, employees in municipalities, shaweesh (an intermediary whose role has expanded since the displacement of Syrians to Lebanon from organising Syrian seasonal farm labourers to including managerial responsibilities towards residents of any given informal tented settlement) in camps, business owners engaged in humanitarian aid economies, and financial institutions invested in refugee welfare, among others. Those one-on-one meetings were crucial to introduce them to the project, and to ensure their collaboration throughout the diverse phases of the research, as well as to ensure their voices are included. Towards the end of the project, we held a stakeholder meeting including those stakeholders, but also activists and members of the refugee communities, and academia, in order to present our findings, hear their recommendations, and plan ahead.

Overall, stakeholder engagement helped us to create a better research design and enhanced the quality of our findings. The stakeholders we spoke to had better knowledge about the needs, priorities and interests of those who are directly affected and participating in the displacement economy. They were also more familiar with the ins and outs of everyday life. Their input allowed us to design better questions that made sense in the local context and to create more effectively targeted interventions. They also helped us to ensure that the data collected was accurate and valid, and they had the perspective to see potential blind spots that researchers may have had.

The stakeholders we spoke to also acted as mediators within the community. Their inclusion in the research helped us create a sense of ownership, since they were directly involved in the project from the very beginning. This is particularly true since the project was responding to the needs and priorities of the refugees, and was community centered. Stakeholders’ important networks facilitated collaboration and partnerships with other experts and community elites.

The inclusion of those stakeholders also made it more likely that any interventions would be better accepted and have a more meaningful and sustainable impact. Furthermore, stakeholders themselves can be targets in the future for capacity building and empowerment, which can have a great added value effect in the community, now that we understand them better.

One point to note is that stakeholder inclusion can be ethical and socially responsible if done correctly. It is important to recognise that stakeholders carry their own authority locally and may direct research findings in specific directions and not others. It is important to conduct stakeholder consultations in ways that respect the autonomy, dignity and rights of the individuals and communities being researched to ensure that all voices are heard.

Key findings from Lebanon

Displacement-affected communities

Lebanon has a rich history of providing refuge and experiencing displacement, with various waves of refugees arriving throughout the years. The PDE research project focused on three selected regions: Nabaa in Beirut, El-Qebbeh in Tripoli and Bar Elias in the Bekaa Valley. Each region had its own unique characteristics when it came to integration, cohesion and tensions among the displaced population.

Understanding the dynamics of integration, cohesion, and tensions in each region requires acknowledging the complexities inherent within them. Factors such as historical context, economic conditions, and social networks play crucial roles in shaping these dynamics. By considering these multifaceted elements, we can gain a comprehensive understanding of the interplay between refugees and host communities, and the various challenges and opportunities that arise.

In Tripoli, the cohesion and integration of refugees stood out compared to the other regions. Strong bonds formed through kinship and intermarriage relationships played a vital role in fostering acceptance and integration. This close-knit network creates a sense of belonging and security for refugees, resulting in a more harmonious coexistence with the host community. Nabaa, on the other hand, faces challenges in achieving integration and cohesion. Despite its long history of hosting refugees and attracting economic migrants from diverse regions, the Nabaa area experiences heightened tensions amid the ongoing economic crisis and resource constraints. However, refugees and migrants were still drawn to Nabaa due to the presence of multiple organisations offering support and the potential for higher wages. The Bekaa region has the largest refugee population, with informal settlements scattered throughout. Despite the challenging living conditions, the Bekaa region exhibited a higher level of cohesion and integration. Even before the Syrian crisis, Syrian economic migrants had a significant presence in the area, fostering familial and trade relationships with the host community.

Findings from the oral history interviews

A total of 250 oral history interviews were conducted across three rounds, involving 150 participants from the research sites. The sample size was evenly distributed, with 50 participants from each site. The interviews included a balanced representation of male and female participants, with 63 males and 87 females, reflecting the population distribution within the sites. While the majority of interviewees were Syrians, there was also a small number of Lebanese participants in the pool.

The narratives shared by the interviewees were significantly shaped by the evolving situation in Lebanon, particularly in relation to the daily challenges and future prospects discussed by the refugees. The first round of interviews took place in 2022, during a time when sustainable daily products were still subsidised and the Covid-19 situation was gradually improving. In the second round, conducted in January 2023, the interviews occurred amidst a period of heightened economic instability, with a steep increase in the exchange rate. During this time, the government decided to remove all subsidies, which further impacted the daily lives of the refugees. The third round of interviews, held in May 2023, coincided with a deportation campaign that created an atmosphere of fear and uncertainty. Throughout each period, the narratives provided insights into the direct impact of these circumstances on the daily lives of the refugees, as well as the adaptive strategies they employed in response to the challenges they faced.

After analysing the interviews, we classified the responses into seven distinct areas, focusing on various aspects related to the displacement economy. This categorisation allows for a comprehensive understanding of the economic dynamics and their effects on the lives of the refugees.

Housing

In the initial round of interviews, housing emerged as the primary concern for almost all participants. Ninety-seven per cent of respondents did not own their own housing. According to Lebanese law, refugees are not allowed to own any assets, and there are laws that limit the type of structures that refugees can live in. A remarkable 94% expressed that their greatest worry was the cost of rent, sharing negative experiences with landlords who imposed exorbitant charges and many shared experiences of discrimination. However, despite these challenges, a significant number of respondents maintained positive relationships with the surrounding community, particularly within the host communities. Relations may be better between Syrians and their low-income Lebanese neighbours who sometimes share resources to acquire basic services.

In the subsequent round of interviews, a majority of participants had relocated to inferior housing conditions in order to afford their rents. This highlighted the sacrifices made by refugees to meet their housing needs. During the third round, the prominence of housing as a topic decreased. Instead, there was a greater emphasis on finding places or neighbourhoods where Syrian refugees were more accepted, with specific attention given to the Nabaa region in Beirut.

Education and training

Education holds significant significance for Syrian refugees, particularly given the high illiteracy rate of around 90% in their home country. In the initial round of interviews, refugees expressed deep concerns regarding the quality of their children’s education. They were determined to secure access to education, whether through formal or informal means, along with vocational training opportunities for improved prospects. During the second round, economic hardships and a sharp rise in the US dollar exchange rate compelled many families to withdraw their male children from schools, aiming to alleviate financial pressures. In the third round, the fear of law enforcement targeting their parents resulted in a situation where numerous children, despite having the opportunity to attend school, were removed from educational institutions. This fear became a deterrent to their continued education.

The reputation of informal education centres was mixed, with slightly less than a third responding that they preferred informal education centres run by NGOs to public schools.

About a third of female respondents had received some form of vocational training compared to almost none of the male respondents. However, only five of the female respondents shared that their vocational training had helped them in their work, highlighting the ineffectiveness of vocational training that is not connected to work opportunities.

Reallocation and refoulement

The topic of relocation and refoulement underwent significant transformations through the three rounds of interviews. During the first round, it was a concern that occupied the thoughts of respondents. However, as we progressed to the final round, it transformed into a genuine and alarming threat. Approximately 50% of the respondents refused to participate in the interviews of the third round, and those who did were accompanied by their families out of fear of potential arrests on the roads or within the centres. This apprehension was heightened due to real actions taken by law enforcement against Syrian refugees, including cases of refoulement where some refugees were sent back to the Syrian border or handed over to the Syrian regime, resulting in the subsequent disappearance of some individuals. This shift underscores the escalating anxieties and uncertainties surrounding the issue of relocation and refoulement faced by the refugee population.

All Syrian interviewees were concerned about the possibility of being forcibly returned to Syria. These fears stemmed from a concern that they would be conscripted into military service or persecuted. Female respondents were worried about their husbands and sons being conscripted. Of those interviewed, only 24 had returned to Syria since their displacement. Ninety-two per cent of interviewees have a desire to be resettled in a county other than Lebanon although most do not understand the criteria the UNHCR uses to allow resettlement or travel. In general, most interviewees complained about the lack of clarity in UNHCR policies, with many stating that refugees have been cut off and reinstated without any apparent reason.

A low number of interviewees (13) were thinking of relocating illegally, and these were almost all young men. It is worth noting, however, that this question’s potential implications of illegality may have influenced responses.

Debt and mutual aid

In Lebanon, being a refugee often entails grappling with debt. During our interviews, all participants acknowledged having debts to stores, landlords or even relatives. However, as we delved deeper into the interviews through the three rounds, we uncovered a significant trend: amidst the intensifying crisis, there has been an escalating reliance on mutual aid and support networks among both refugees and host communities, primarily facilitated by their relatives and acquaintances. This interdependence plays a pivotal role, particularly as support from formal organisations becomes more limited and constrained.

Ninety per cent of respondents had some form of debt. The most common holder of debt was a landlord, a store or friend. Ninety-four per cent of respondents shared that the amount of aid they were receiving had decreased since the beginning of their displacement and that it had decreased to a point of scarcity.

Eighty-seven per cent of those interviewed stated that they would provide or ask for unremunerated help from relatives.

Only 19% of those interviewed were receiving remittances. Traditional modes of remittances do not form a regular part of the income of refugees and are only used in exceptional circumstances to pay debts or for medical procedures.

The worsening economic situation has pushed many refugees into precarious financial circumstances, leading to a reliance on informal networks of support. This mutual aid system involves individuals assisting one another through financial loans, sharing resources or providing practical assistance. It serves as a coping mechanism to navigate the challenges of debt and financial strain.

Healthcare and care

The issue of medical treatment is a significant concern for refugees, especially considering that 7% of the refugee population has some form of disability. Additionally, many respondents in the baseline survey reported being burdened with debts related to medical treatment costs. The findings from the first round of interviews aligned with the baseline data, highlighting the high costs of medical treatment and the reliance on NGOs and dispensaries for urgent medical needs. Ninety-seven per cent of those interviewed could not afford the medicine they needed. Eighty-six per cent of those interviewed shared that they were unable to eat properly, meaning they did not have access to meat, poultry or dairy products. Some respondents said they relied on their relatives in Syria to provide them with necessary medicines and some refugees even mentioned travelling to Syria for surgery because the costs were lower. This is risky, since doing so could jeopardise their eligibility for UNHCR assistance. In the second and third rounds of interviews, the issue of medical treatment became even more pronounced. Many respondents expressed that unless their condition was life-threatening, they would forego seeking medical care due to the exorbitant costs of consultations and medications.

Family care emerged as a prevalent practice across all three rounds of interviews, with women playing a significant role in providing care for individuals with disabilities, the elderly and young children. However, there were slight variations in the primary providers of care among the different regions.

Seventy-eight per cent of respondents are registered with UNHCR and some receive food vouchers and assistance. Yet despite registration, many refugees do not gain many or any benefits from UNHCR. A majority of interviewees shared that they had been denied admittance at UNHCR-affiliated hospitals. People who entered after 2015 do not receive any form of aid even if they are registered with UNHCR. Yet many register in the hopes that they may be reallocated. UNHCR cards have also been used as collateral or in order to obtain cash.

Thirty-five per cent of interviewees had someone in their family who needed constant care. Women are the primary actors in the care economy, and women’s household care includes childcare, housework and care for the sick.

Safety

Refugees in Lebanon initially experienced a welcoming and safe atmosphere upon their arrival but over time their situation underwent significant changes. The escalation of the economic crisis was accompanied by a growing sense of insecurity for refugees, as they were often blamed as the primary cause of the country’s economic and financial collapse.

The increasing feeling of insecurity among refugees became apparent throughout the rounds of interviews. In the first round, 54% of the interviewees expressed feeling unsafe in their neighbourhoods. This percentage rose to 87% in the second round, and in the final round, all of the interviewees expressed concerns about safety in their neighbourhoods and the country as a whole.

Fifty-six per cent of respondents reported a degradation in the security standards in their neighbourhood, with an increase in violence, tensions and hate speech. Most interviewees said they would not contact the police if they were being harmed because they had no trust in them.

Labour and savings

During the first round of interviews, refugees expressed a clear preference for finding employment opportunities to provide for their families. In fact, 72% of respondents in the first round identified employment as their primary source of income. Additionally, a significant number of respondents, approximately one in three, relied on their children’s labour to supplement their income. Unfortunately, many children were involved in high-risk forms of child labour, including garbage collection, begging, and engaging in electrical and construction work.

As the interviews progressed into the second round, there was a noticeable increase in the number of children involved in the workforce. This trend reached its peak in the third round, driven by factors such as the ongoing arrest campaign and the restrictions faced by adult men in terms of movement and employment opportunities. Moreover, employers became more hesitant to hire undocumented refugees, exacerbating the reliance on child labour for economic survival.

As time went on, the living standards of refugees significantly declined, and none of the interviewees reported having any form of savings or the ability to sustain themselves for the upcoming month.

Interviewees shared that prior to the 2019 economic and financial crisis in Lebanon, they had a ‘good’ standard of living. Since then, two-thirds of respondents had lost their savings, either because of Covid-19 or because of the financial crisis. Almost all respondents were unable to save any money, and 87% shared that they could not afford to go out and visit relatives.

Differences between sites

In addition to the common challenges faced by all refugees in each of the sites, there were unique features that distinguished the sites from one another. In Bekaa, most refugees live in camps and are more reliant on aid than in the other locations. The residents of the camps are less skilled, and most are employed in agriculture. Women play an outsized role in the Bekaa region, both as household heads and as agricultural labourers. There are the fewest employment opportunities in Bekaa, potentially because of the rural location of the site.

Nabaa being located in the capital of Beirut is the beneficiary of a number of feedback loops that improve levels of social trust and mutual aid. Because of its location, most of the training programmes take place in Nabaa. Refugees there have higher levels of education, and higher levels of mutual aid and care. Similarly, the central location also allows more refugees find work in the NGO sector, although the cost of living in Nabaa is higher than in the other two sites. There is a broader network of mutual aid and social trust and unlike in the other sites where money lending takes place between relatives, friends also lend each other money.

Tripoli differs from the other sites because kinship and intermarriage between refugees and the host community are more common. Tripoli also has the lowest rate of school enrolment for children.

Feminist economies and mutual aid

There is a distinct division between the themes addressed by men and women in the transcripts. Women’s transcripts tend to cover food insecurity more often than men, as most of them oversee the nourishment of the family. Furthermore, these transcripts also tend to expand more on health issues and relate to the entire family. We found that women highlighted sharing their problems, experiences and providing comfort as a form of mutual aid among them, while providing comfort was not necessarily recognised by men as a form of mutual aid. Men’s transcripts focus on the economic situation, the struggle to find a suitable job and earn enough money.

Women are the primary caregivers in the three sites; this includes young women taking care of domestic work and providing care to siblings, as well as older women who take care of their grandchildren. Interviews show that, as women start working in part-time or full-time paid jobs, they either continue to undertake unpaid care work or transfer this work to other women within the household. In Nabaa, the workload and responsibility of care tended to be transferred to young women. In Tripoli, older women claimed to take on these responsibilities for their daughters. However, in Bekaa, women reported working in paid jobs and looking after their families simultaneously. This redistribution of care among women is problematic as it perpetuates the gendered division of labour and reinforces gender norms and expectations, while men are expected to focus on paid work outside the home.

Interviews also showed that women who work in part-time jobs are often overburdened as they are still responsible for significant amounts of unpaid care work and have less time and energy for other activities. Moreover, as there is an expectation for women to take on these diverse responsibilities, they tend to prefer flexible jobs that are often low paid and labour intensive. A woman in Bekaa shared:

I work in the field. I pick up vegetables. I work at night and in the early morning before my kids wake up, I go with my neighbours to work.

The concerning aspect of this dynamic is that the unequal division of unpaid care work emphasises the vulnerability of women who have an irregular migration status, economic difficulties and/or disabilities. In comparison with men, these women may face even more barriers to access support services and may have fewer resources to rely on when they are providing care.

Women also suffer from internal and external social stigmas against work. In Tripoli, women who rely on female relatives for childcare feel guilty for not having enough time to spend with their children. In all three sites, there are women who have declined or left jobs to care for their children.

There is a potential for the desperation caused by the dire economic situation to disrupt traditional gender roles by allowing women to enter the labour market. As a 61-year-old male interviewee from a conservative rural background in Aleppo province now residing in the Bekaa stated:

I am against the idea of women working, but the situation made me accept the idea.

Unfortunately, in many cases women take on the double burden of doing unpaid work at home and doing undervalued work outside of the house.

Transcripts reveal a pattern of undervalued and unrecognised paid labour performed by women. Their work is often seen as mere ‘assistance’ instead of a legitimate source of income. This perspective enforces gender-based inequality and fails to recognise the valuable economic contribution of women to the household. This unequal power dynamic within households has significant implications for women’s economic empowerment, making the situation in Tripoli, the site with greater numbers of women working in full-time jobs, a particularly interesting issue to analyse.

Gendered violence

Women in all three sites experienced forms of gender violence. Among these were being denied their right to education and health, being physically beaten by their partners and close relatives, and experiencing diverse forms of sexual violence such as unwanted sexual advances, harassment and physical contact. These cases were more prevalent in Bekaa (most interviews related to gender violence were done by a single researcher.

How does the market work in protracted displacement economies?

Displacement-affected communities in Lebanon struggle with job insecurity as formal jobs and business opportunities are impacted by displacement. Limited opportunities in the formal economy push Syrian labour and enterprise into informal and less documented aspects of the economy. The effects of which have been well documented elsewhere. Less understood is the impact on other members of the displacement-affected community – those already resident. As one grocery store owner in the Bekaa told us:

Even Lebanese citizens bought from markets owned by Syrians because they had cheaper prices. I tried to decrease my profit, but it wasn’t beneficial at all. I have a family and my mother lives with me. We have high expenditure. We own cars, we pay for electricity and many other expenses. In Lebanon, there is a law that prohibits people from owning businesses, but no one abides by it, and law enforcement does not intervene. These markets do not have permits and do not pay taxes either. Unlike us, who must pay taxes and rely solely on our businesses for income, all of their profits go directly into their pockets.

This, along with the financial crisis that has diminished the purchasing power of those who earn Lebanese pounds, has led communities to frequently resort to transactions of labour for goods and services rather than relying on monetary compensation. Respondents in Bekaa tended to work in precarious daily jobs, that include agriculture and manual labour, through which they often get access to housing. These tend to be informal jobs that entail physical effort and are performed in harsh conditions. Meanwhile, in Nabaa and Tripoli, interviews were performed mostly with Lebanese and Syrians that ran businesses or engaged in formal employment.

Syrians in Lebanon face numerous employment challenges, including restrictions on their ability to work, high job insecurity, unequal pay for doing the same jobs as Lebanese citizens, and limited access to certain occupations. This situation, in turn, has forced people to constantly move within Lebanon to access job opportunities and, in some cases, has separated families. In all cases, refugees are unable to cover household needs using salaries alone. They must also rely on diminishing international aid from UNHCR, WFP and other aid agencies to survive. A 38-year-old woman in Tripoli told us:

If the UNHCR cut me off from the programme and stopped giving me funds, it would be a disaster. I won’t be able to pay my debts anymore. Also, I would have to borrow more money, and I wouldn’t be able to pay my older debts.

From the perspective of the individual, the protracted displacement economy is defined by the low availability of income-earning opportunities (which are insufficient when found), high levels of labour competition, and a fierce competition over a limited and poor stock of housing.

The presence of Syrian refugees has significantly impacted Lebanon’s labour market, resulting in increased competition for low-skilled jobs and widespread informality, exploitation and inadequate working conditions for both Lebanese and Syrian workers. In Bekaa, for example, the labour market has undergone a transformation as a result of the new legal barriers faced by Syrians to work and operate businesses, leaving Syrians in a situation of vulnerability. As a shop owner in Bekaa stated:

Syrian employees typically earn lower wages and work longer hours than the Lebanese.

Because of the high supply of labour and insufficient pay, refugees are in chronic and pervasive debt. Interviewees in all sites have stated that the limited money they earn from work, international aid (only for those recognised as ‘refugees’), or the Lebanese government (only available to Lebanese), is spent on basic needs such as food, healthcare, gas and the private electric generators. There is no record of money being spent on leisure, while there are some cases of respondents saving or investing in business. As the prices in the country have escalated, basic services within the household have become the main expenditure. Any additional expenses, such as chronic medical treatments or paying smugglers to travel abroad, are significant financial burdens. Most interviewees are caught in a cycle of work and debt, which consists of borrowing from relatives and friends or using credit to meet basic needs and repay debts when they receive a stipend or secure a day job.

The use of debt and barter is premised on social trust and is necessary for enabling transactions in the protracted displacement economy. While this fulfils a key need in the market, it is not without its limitations. Respondents have reported losing money from extending credit and facing difficulties in ordering merchandise as suppliers and landlords demand their payment in ‘fresh dollars’.

Finally, the largest and most stressful expenditure for refugees is rent. Relationships with landlords are often stressful and leasing behaviour can be unpredictable. Housing experiences vary across sites. In urban areas, interviewees directly deal with the person leasing their housing. In the more rural area of the Bekaa region, most refugees live in camps, and housing is managed by a shaweesh, an intermediary between distant landowners and camp residents. Most transcripts show that the shaweesh frequently mistreats workers and overcharges them for services and goods in the camp. In some camps, labour in the fields is sometimes traded for permission to reside in the camp, which has been deemed exploitative by some of the respondents.

Tensions between host and refugee communities

The 2019 financial crisis exacerbated and intensified tensions between Lebanese and Syrian labourers and shop owners. The relationship between host and refugee communities is complicated, with examples of both cruelty and discrimination, as well as solidarity.

For example, competition for market share between shop owners in all sites is high. The overall problem, as stated by the shop owners, is that customers from various nationalities, including Lebanese, Syrian, Palestinian and Ethiopian, have reduced their consumption. Shop owners claim people are unable to buy goods as they did before.

Because of their networks in Syria, Syrian shopkeepers are able to provide lower prices and bring cheaper products from Syria. This can cause resentment, and in Nabaa, Syrian shop owners who work illegally are being reported to Lebanese authorities. At the same time, Lebanese shop owners in the Bekaa take advantage of the availability of Syrians because they can pay them lower wages.

However, conversely, there are also examples of continued solidarity. When Syrian shop owners are confronted by authorities in Nabaa, in order to avoid closure, the legitimate Lebanese owner or a close Lebanese associate or friend often steps forward to claim ownership of the business averting a confrontation. In the Bekaa region, shop owners also hire Syrian workers to attract other Syrian customers. This is a noteworthy trend as shop owners claim that Syrians tend to shop at establishments run by other Syrians. A Lebanese grocery store owner in the Bekaa spoke of their positive experience of hiring a Syrian employee:

When you hire a Syrian, his relatives and friends will shop at our market.

Syrian refugees in Bekaa have access to a monthly UNHCR stipend. By hiring Syrians, customers become familiar with the shop owner, spend their stipend at their store, and can buy on credit when needed. In return, shop owners can keep their businesses running, attract regular customers, and introduce Syrian products to their shops to meet demand. This approach has enabled businesses to continue operating despite the drop in sales caused by the financial crisis.

The changing availability of aid and worsening economic situation have also fed into inaccurate perceptions about refugees by the host community. There is still a pervasive idea among Lebanese residents that refugees are better provisioned than they are. The lack of clarity around the way aid is distributed has accentuated differences between ‘refugees’ and ‘host’ communities. Registered refugees receive support for a limited amount of time from UNHCR and the WFP. This help consists of money (UNHCR) and food boxes (WFP) and was highlighted as the main resource respondents from Syria used to cover living expenses. Amid this situation and the ongoing crisis in the country, Lebanese citizens claimed those recognised as refugees were receiving more support and opportunities than them. Often the level of social assistance and protection Syrians are eligible for is exaggerated by local Lebanese residents in the same neighbourhoods. A 67-year-old shopkeeper in the Nabaa neighbourhood of Beirut told us:

Foreigners living in our country have more money and they can spend more than the Lebanese. The Syrians and the Palestinians receive funds from international organisations, and they can spend more. They receive money in dollars, they do not have to pay for schools or medicine or hospitals. They can afford to buy more than the Lebanese. They buy meat and chicken more than once a week.

Sustainability

The sources of hardship for members of the displacement-affected community are common to both Lebanese and Syrian refugees, as well as members of other nationalities that are part of the displacement economy. The framework of displacement-affected communities offers a more inclusive and comprehensive perspective compared to the typical refugee versus host community dichotomy. While the traditional framework focuses on distinguishing between two distinct groups, the displacement-affected communities approach recognises that both refugees and host communities are impacted by displacement and face various challenges.

The framework allows a more comprehensive understanding of the situation in displacement-affected communities and enables more productive interventions. Displacement affects both refugees and host communities in multiple ways. They may experience strain on resources, increased competition for jobs, pressure on public services and social tensions. Recognising these shared challenges helps foster empathy, understanding and collaboration between different groups.

By shifting the focus from a binary division to a broader understanding of displacement-affected communities, it becomes possible to promote social cohesion and integration. Instead of viewing refugees and host communities as separate entities, efforts can be made to foster mutual support, cultural exchange and shared spaces.

Displacement affects individuals and communities differently, and vulnerabilities can exist within both refugee and host communities. By adopting a displacement-affected communities framework, it becomes easier to identify and address the specific needs and vulnerabilities of all affected populations, regardless of their status.

This is particularly true of the patterns and dynamics of unpaid care work and paid work by women. Shifting the framework of analysis away from nationality opens up insights into the importance of women’s day-to-day activities in the displacement-affected economy. It also highlights the continuing and changing power dynamics in families brought about by economic hardship.

Recognising the value of care work remains crucial in protracted displacement contexts. By providing additional support in the form of healthcare and education, the impact of displacement on carers can be alleviated. This can include alternative care arrangements, such as redistributing care with a partner or agreeing on community-based care services. Women’s experiences in protracted displacement settings reveal accentuated dynamics of gender inequality that determine their participation in the economy – their stories must be heard by and visible to their families, the state, the market and the non-profit sector.

Host communities often possess valuable local knowledge, resources and networks that can contribute to the well-being and resilience of both refugees and themselves. Recognising this can lead to more effective interventions and strategies that leverage the strengths and capacities of all members of the displacement-affected communities.

Finally, the dichotomous view of refugee versus host feeds into harmful narratives about refugees in the host community and can perpetuate stereotypes and stigmatisation. Lebanese interviewees continue to accept the narrative that refugees are an economic burden. This is convenient for the political elite in the country, who can shift blame to refugees for a host of endemic problems in the country that they are responsible for. A more inclusive framework, looking at the displacement-affected community as a whole, combats narratives of blame and opens up opportunities for drawing on common resources.

It is important to note that while the concept of displacement-affected communities provides a more holistic approach, it does not negate the specific protection needs and rights of refugees. It simply broadens the lens to recognise the complex dynamics and interdependencies among different groups affected by displacement.

The humanitarian anchor

Our research on displacement-affected communities has highlighted numerous examples of sustainability, demonstrating how community members invest in and support each other in both financial and non-financial terms. These examples showcase the resilience and resourcefulness of displaced communities in challenging circumstances.

In terms of financial sustainability, we observed instances where community members established their own businesses or engaged in entrepreneurial activities. These initiatives not only generated income for individuals but also contributed to the local economy and provided employment opportunities for others within the community. We witnessed the creation of small-scale enterprises such as shops, market stalls and artisan workshops, which allowed community members to sustain themselves and their families. One Syrian who acted as a camp shaweesh in the Bekaa told us:

Being knowledgeable in agriculture, I rented land from a Lebanese landlord. I started with Armenian cucumbers, cultivated crops and sold the harvest, utilising my expertise to determine suitable land. The venture proved profitable, with earnings reaching US$10,000 each season. We also employed several other Syrian workers during this time.

In addition to financial aspects, non-financial sustainability practices are prevalent among displaced communities. Individuals come together to support each other through informal networks, sharing resources, knowledge and skills. This collaborative approach allows community members to address their immediate needs, such as food, shelter and healthcare, while also fostering a sense of solidarity and belonging. This sense of community extended beyond displacement-affected localities and reached out to diaspora actors located beyond countries neighbouring Syria. Research has shown the formation of associations, community groups and support networks where individuals provide assistance to one another. A 50-year-old Syrian craftsman in Tripoli told us:

For a period of approximately two to three years, I was actively involved with an organisation of 10 to 12 individuals from Homs, Syria. Our collective initiative stemmed from witnessing the plight of Syrian families within the region. Generous Syrian traders, particularly those residing abroad, supported our cause by providing essential items such as milk, bread, clothes and financial assistance.

There was also mutual assistance between different displaced populations – notably Palestinians and newly displaced Syrians. A 22-year-old woman told us:

My mother, who worked as an art teacher, selflessly volunteered at a mosque in al Baddawi [a Palestinian refugee camp in Tripoli]. Although my mother did not receive any financial compensation, there were instances when she would be gifted food baskets as a token of gratitude.