7 Pakistan

Ceri Oeppen; Shahida Aman; Muhammed Ayub Jan; and Abdul Rauf

Country context

Since 1979 (the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan), and throughout the subsequent and ongoing conflicts and crises, millions of Afghans have been displaced to Pakistan. At its peak, in 1989, the registered Afghan refugee population in Pakistan was over 3 million (UNHCR, 2000).[1] Our research was conducted in the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, which borders Afghanistan (see Figure 1) and is home to just over half of all the Afghans in Pakistan (EUAA, 2022). Historically, there has been extensive mobility between what is now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Afghanistan (Dupree, 1973; Ghobadi et al., 2005; Haroon, 2007; Marsden & Hopkins, 2012). The de facto border (‘The Durand Line’) between Afghanistan and Pakistan was defined by British colonialists in 1893, and where it borders Khyber Pakhtunkhwa it divides an area where the majority ethno-linguistic group on both sides is Pashtun. Although there are people from all Afghan ethnic groups in Pakistan, the vast majority (86%) of registered Afghan refugees are Pashtun (UNHCR, 2023).

During the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan (1979-1989), Pakistan received millions of Afghans and served as a base for the Afghan mujahideen[2] to regroup and organise. Whilst the international community recognised the majority as refugees, that was only one part of their identity in relation to the resident population in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, as the anthropologists, Centlivres and Centlivres-Demont (1988, p. 144) pointed out at the time:

…rather than victims, accepted according to humanitarian law, one could perceive them [Afghan refugees] – at least in the beginning of that enormous migration – as beneficiaries of traditional hospitality offered by the Pakistanis of the NWFP [now, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa] to their brothers from the other side of the border. Indeed, it was not just any hospitality, but one dictated by the strict norms of the pushtunwali code of honour as practiced by the Pushtuns.

From this viewpoint, the image that these ‘refugees’ offer of themselves is not one of a mass of unarmed and helpless individuals, but one of organized groups seeking temporary shelter among kin.

This contemporary observation during the first decade of Afghan displacement to Pakistan illustrates well one of the key ideas behind the Protracted Displacement Economies (PDE) project more widely – that the representation of a clear ‘refugee’-‘host’, or ‘victim’-‘giver’, distinction is an over-simplification of most displacement-affected communities. To add to the complexity, Afghans fleeing the Soviet occupation also represented themselves in Islamic terms, as mohajir (ibid.).[3]

The conflict between the Soviets and mujahideen was a key theatre of the Cold War, and Western powers channelled huge amounts of aid (and weapons and other resources) to the mujahideen via the Gulf States and Pakistan. Despite the difficulties of exile many of our older research participants remembered this era as a very different time, at least in terms of access to aid. As one interviewee in Chitral said,

Afghans passed through a lot of distress and trauma. At one time there was some facilitation provided to us. It was the time when there were rations [food aid] available. However, when the mujahideen succeeded and the Soviet Union disintegrated we got into hardship because all the aid stopped.

Since the Soviet withdrawal in 1989, the conflict in Afghanistan has been through several variations: a civil war between mujahideen groups battling to fill the power vacuum left by the Soviets; the first Taliban rule (1996-2001); the US-led NATO occupation and related insurgency; and, most recently, the regain of power by the Taliban in 2021. Consequently, the Afghan population in Pakistan, and the Pakistani population and government responses to them, has evolved and changed. Whilst at various stages many hundreds of thousands of Afghans have returned to Afghanistan, others have been newly, or repeatedly, displaced. It is estimated that more than half of the Afghan population has ‘migrated’ since the conflict was first triggered by the Communist coup and killing of President Daud Khan in 1978 (Harpviken, 2009), predominantly to Pakistan, and Iran.

A fuller contextual account of the Afghan conflict(s) and related population displacement is covered elsewhere (see e.g., Dorronsoro, 2005; Gopal, 2015; Harpviken, 2009; Jamal & Maley, 2023; Monsutti, 2020; Safri, 2011), but this brief macro-level overview suggests a few key points. Firstly, there are socio-cultural (ethno-linguistic and religious) reasons why Afghans (particularly Pashtun Afghans) have been sheltered by the ‘local’ population in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Secondly, the geopolitics of the conflict in Afghanistan has led international and regional interest in providing aid and other support to Afghan refugees to wax and wane over time, with a significant drop-off after the Soviet withdrawal. Thirdly, the ‘global war on terror’ post-11 September 2001 has meant increased securitisation in the region and, relatedly, increased negativity towards Afghans (Mielke & Etzold, 2022; Safri, 2011). This has led to the increased control of the Afghanistan-Pakistan border, including 2,640km of border fencing, as well as the promotion of return migration and phases of deportations by the Pakistani government; including, at the time of writing, the deportation of over 800,000 Afghans (BBC News, 2025) since the launch in late 2023 of the ‘Illegal Foreigners’ Repatriation Plan’. Fourthly, the Taliban regaining power has seen new displacement from Afghanistan, as well as decreasing the likelihood of large-scale ‘voluntary’ return migration from Pakistan.

We turn now to the current situation of Afghans in Pakistan, an indication of population size, and the policy and regulatory frameworks shaping their living conditions. The umbrella term ‘Afghans in Pakistan’ encompasses Afghans living in a range of bureaucratic categories, including recognised refugees, undocumented and documented migrants. Additionally, the protracted nature of the conflict in Afghanistan (over 40 years) means there are likely more than 2 million people of Afghan origin, born in Pakistan, who may or may not have Afghan nationality documents, and are unable to access Pakistani citizenship.[4]

Whilst most Afghans in Pakistan might be recognised as refugees in a socio-cultural sense, not all are registered with the Pakistan authorities as recognised refugees with Proof of Registration (PoR) cards,[5] or identified as refugees by UNHCR. Other categories include those with Afghan Citizen Cards (ACC),[6] Afghans on business or visitor visas and undocumented Afghans. This mix of statuses means that secondary data on the population of Afghans in Pakistan must be estimated from multiple sources, including: Pakistan’s Commissionerate for Afghan Refugees (CAR), which is under the auspices of the Ministry of States and Frontier Regions (SAFRON); Pakistan’s National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA); the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR); and the International Organization for Migration (IOM). An additional secondary data source we found useful during the PDE fieldwork was Pakistan’s Basic Health Units (BHUs), which tend to have some of the most up-to-date data on Afghan populations at the local level.

According to UNHCR (2023), just under a third (31%)[7] of registered Afghan refugees live in the officially designated ‘Afghan Refugee Villages’ (refugee camps), which are – officially at least – only accessible to PoR card holders (ADSP, 2018). These ‘villages’ are managed by CAR, with support from UNHCR. Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) may only operate in them with CAR’s permission. Meanwhile, the majority of Afghans in Pakistan live in urban or peri-urban areas, including in and around Peshawar, Quetta, Islamabad and Karachi (Alimia, 2023).

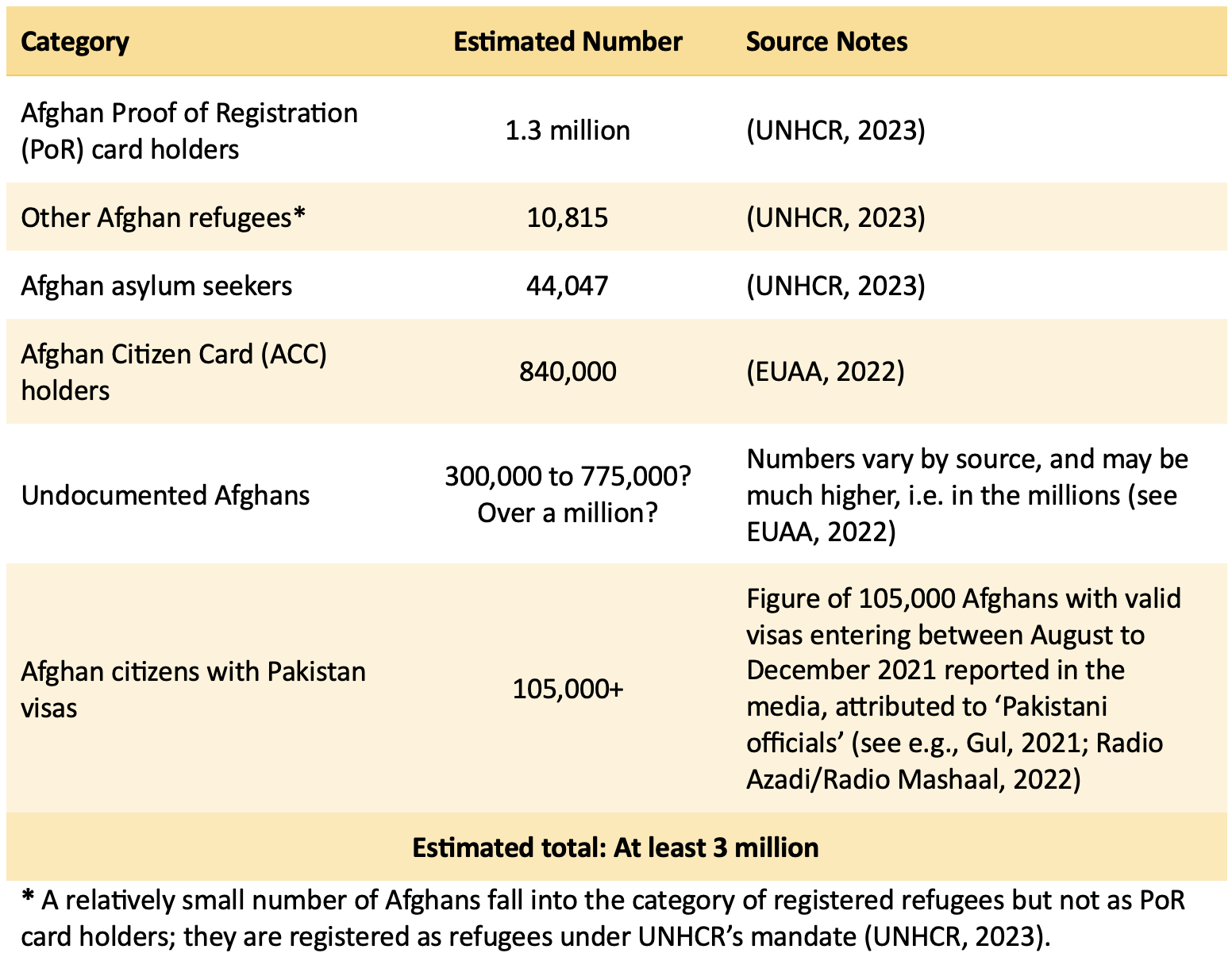

Table 1 gives an indication of the estimated size of the Afghan population in Pakistan – of at least 3 million people. Refugees, migrants and other precariously situated populations, including undocumented migrants, are notoriously difficult to accurately count, so these figures should only be seen as indicative. This is further complicated by limited data on numbers of new arrivals since August 2021. A senior CAR official estimated that around 300,000-500,000 had arrived but admitted that it was hard to know exact numbers because of undocumented border crossings and the limited data collection at the Spin Boldak/Chaman border crossing.[8] Research participants in Peshawar told the PDE team that many of the ‘new arrivals’ that had come to Peshawar since 2021 were Afghans who had previously lived in Pakistan and had either been deported, or returned, to Afghanistan in the preceding few years.[9]

Regulatory frameworks for Afghans in Pakistan

Although Pakistan is not a signatory to the UN’s 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, it has allowed UNHCR to operate within its borders and UNHCR was particularly active in the 1980s, alongside other international agencies, and then again in the last two decades, in relation to the facilitation of repatriation. Ultimately, the government of Pakistan is responsible for regulations relating to Afghans, but despite some previous efforts to establish one there is no refugee law per se in Pakistan.

CAR, operating under the auspices of SAFRON, is the main administrator of Afghan refugee populations in Pakistan, managing camps and coordinating access to education and healthcare, sometimes in partnership with UNHCR or NGOs. A detailed analysis of the regulatory frameworks and responsibilities shaping institutional responses[10] to Afghans in Pakistan is available elsewhere (see e.g., ADSP, 2018; Ahmad, 2017; Alimia, 2019, 2022; EUAA, 2022). Nevertheless, we highlight some key regulatory issues of relevance to the PDE project.

Most significant are the issues around naturalisation or other forms of legal residency (see Oeppen et al., 2023), which the majority of Afghans do not have. Despite the fact that most Afghans in Pakistan were born there (likely around three-quarters, see SAFRON/CAR/ UNHCR, 2012), the vast majority of Afghans are not able to naturalise their status in Pakistan. Although people born in Pakistan after 1951 are technically allowed to gain Pakistani citizenship, this has not included refugees (the Pakistan Citizenship Act, 1951).[11] A minority of those with significant financial and social capital resources have done so through business contacts and illicit means such as the forgery of documents. In 2018, the then newly elected Prime Minister Imran Khan stated that 1.5 million Afghans born in Pakistan would be able to apply for citizenship (Hashim, 2018), but this incited substantial criticism from sections of the public and opposition, including arguments that it was a cynical move on Khan’s part to hugely increase his (traditionally Pashtun) voter base (Barker, 2018; Wasim, 2018), and it was not put in to practice. With Khan’s removal from office in 2022 and his subsequent imprisonment it seems unlikely that this suggestion will be resurrected in the foreseeable future. In reality, the only group of ‘ordinary’ Afghans who are able to access naturalisation are Afghan women married to Pakistani citizens and subsequently their children (Alimia, 2019; The Pakistan Citizenship Act, 1951).

The implications of this lack of access to legal residency (let alone citizenship) are wide-ranging. Key implications relating to the PDE project include the reality that Afghans, as non-citizens, are not able to purchase land, property or businesses, limiting their ability to fully integrate economically, leaving them at higher risk of economic exploitation (and removing potential tax revenues for Pakistan). Government jobs (an important route to relatively secure economic status in Pakistan), even lower-level positions, are impossible for non-citizens to access. It was only recently, since 2019, that Afghans (with PoR cards) were legally able to have a bank account in their name in Pakistan, and even now many barriers remain that prevent access.[12]

Whilst in many ways the Pakistani authorities have been generous to Afghans living in Pakistan, giving land for refugee camps and granting at least partial access to free government education and healthcare, the fragile nature of Afghans’ residency, even after more than 40 years, means that Afghans are left in a precarious position. The waxing and waning (but ever-present) threat of expiring PoR cards, coerced repatriation and deportations leaves people in a limbo-like situation, with negative outcomes for mental and physical health and well-being.

Internal displacement in Pakistan

Whilst discussion of displaced populations in Pakistan tends to focus on Afghans, internal displacement is also a significant, albeit less visible, issue. The government only officially counts and records internal displacement in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, with a focus on the former Federally Administered Tribal Areas. The current internally displaced person (IDP) population there is estimated to be around 21,000 (IDMC, 2023), much lower than the million or so displaced in 2014 in response to conflict in North Waziristan. IDP populations elsewhere in Pakistan are likely dominated by those displaced by the 2022 floods – over 1 million are estimated to still be internally displaced in Sindh and Balochistan as a result (ibid.).

The research process

The fieldwork in Pakistan took place in three locations in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province – Peshawar, Haripur and Chitral (see Figure 1). In keeping with the PDE project’s overall methodology (see ‘Researching Protracted Displacement: The Protracted Displacement Economies Project’ chapter), it comprised a mix of quantitative and qualitative methods. These included:

- a large baseline household survey (n = 3,189 households), a sample of whose participants were also involved in:

- a follow-up panel survey (n = 598 households);

- qualitative semi-structured interviews (n = 272); and

- in-depth oral history interviews (n = nine);

- focus group discussions (12 groups);

- a 10-day documentary film-making workshop (six participants); and

- interviews and community meetings with key informants and stakeholders.

In this section we outline our fieldsite selection; our access and sampling process, including discussion of the challenges faced in data collection; and we provide details on the fieldwork conducted.

Fieldsite selection and community profiles

Figure 1 shows our three fieldsites: one urban (Tehkal, Peshawar); one refugee camp (Haripur Refugee Village); and one more remote, semi-rural mixed site (Drosh, Chitral). These three sites were chosen based on differing geographies and population characteristics, as well as different levels (and possibilities) of government and NGO involvement.

Tehkal, Peshawar

Tehkal is a peri-urban site of Peshawar District, which hosts a mixed population consisting of the local Khalil tribe members, internal migrants, IDPs and Afghan refugees. It is this mix that makes Tehkal an interesting case study of an urban displacement-affected community.

Haripur Refugee Village

Our second fieldsite’s population is almost all Afghan, as it is a refugee camp; this also means it has the highest current level of CAR and NGO involvement of our fieldsites, although this is still relatively low. The Haripur Refugee Village consists of three rural sites – Pannia 1, Pannia 2 and Padhana, near the city of Haripur. It hosts over 100,000 refugees, which makes it the largest concentration of registered Afghan refugees in a camp setting in Pakistan.[13] Most Afghans there are Pashtun, but there are also smaller groups of Hazara, Tajik, Uzbek and Turkmen Afghans.[14]

Drosh, Chitral

Our third fieldsite, Drosh, is mixed. Data was collected in the urban setting of the city of Drosh and two refugee villages (camps), adjoining Drosh, in the Lower Chitral District. The two camps were Kessu, with a recorded population of 1,049, and Kalkatak, with a population of 670 (CAR, 2018). These two camps are situated in the Tehsil (sub-division) of Lower Chitral known as Drosh. This fieldsite is an interesting contrast to Tehkal in Peshawar, as the Afghans (predominantly Pashtun) differ ethnically from the ‘local’ Chitrali population.

Sampling, access and data collection challenges in Pakistan

As discussed above, sources of secondary data vary and are not always consistent. To create a sampling frame for our baseline and panel household surveys, which subsequently formed the basis of our qualitative interviewee selection, we used a combination of information and data sources: 1) maliks (traditional community leaders responsible for sub-sections of populations at the neighbourhood level); 2) CAR offices in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and individual camp security offices working under the auspices of CAR; and 3) Basic Health Unit (BHU) data.

Whilst secondary data was useful in identifying the geographic boundaries of our fieldsites, we had to rely on the maliks’ and other key informants’ local knowledge of the households in their specific sub-section of the community at the micro scale, particularly in Haripur Camp, to create a systematic sample from that location. The non-uniform nature of settlements in our fieldsites, as well as cultural mores, meant that we could not just walk through a neighbourhood and survey every fifth house, but had to select a random sample from a list of households, created in discussion with each malik. In Haripur, it was particularly difficult to make out where one malik‘s area ended and another’s began, so this required daily ongoing negotiation; particularly as, in keeping with our own role in the protracted displacement economy, we paid participants for their time. Whilst increasingly common practice in academic research, paid participation combined with many participants’ limited understanding of academic research caused misconceptions and challenges – for example, people thought we were from an NGO or aid agency. Potential participants would approach us asking to be surveyed, explaining how they were poorer and therefore more deserving of taking part than people who had actually been selected for the sample. Conversely, sampled participants would direct us to other participants who they perceived needed the money more than them. Multiple explanations of sampling protocols and diplomatic discussions were required.

The volatile political situation, common in borderlands and displacement contexts, also caused challenges. Full official permissions and access letters (‘no objections certificates (NOC)) were required from multiple sources to access camps, and less official, but no less important, permissions were needed from community leaders in all settings. In Haripur, in particular, access was limited by security constraints. The camp security office kept track of movements into and out of the camp and collected information on our and our research assistants’ nationality, ethnicity and family background. The camp commander in Haripur limited our access by ensuring we left the camp by 3:30pm each day, meaning that the survey was usually conducted with participants of non-working age on behalf of their household.

The physical distances involved were also a challenge, particularly for female enumerators conducting surveys in Haripur (a three-hour journey each way from and to the University of Peshawar).[15] Facilities in the camp, such as (lack of) access to washroom facilities, as well as the heat and humidity also made it hard. Several situations beyond our control affected our ability to adhere to strict timings of data collection, not least Covid-19, but also an outbreak of Dengue fever, a flood in Haripur and monsoon-related floods closing roads to Chitral.

Accessing female respondents was another specific challenge of the fieldwork in Pakistan, which meant we reduced our plan of half the respondents to the survey being female, to one-third. Despite working with women enumerators, some potential women respondents refused to take part for reasons relating to purdah (culture of gender segregation and limited access of women to public spaces). Women in our fieldsites (particularly older ones) often had only limited education, if any, and had difficulties comprehending the purpose and nature of the survey as a piece of academic research, rather than the work of an NGO or aid agency. Female-headed households were very few, and certainly not enough for statistical comparative analysis.

The panel survey, which required surveying a random sample of participants from the baseline survey (see chapter 2), faced difficulties in relation to locating participants. The PDE quantitative lead, Dr Rajith Lakhsman, provided a sample and we tried to contact people via the mobile phone numbers given in the baseline survey. Whilst this worked for a small selection, inevitably it did not for the majority (particularly women respondents who had not given their mobile numbers for cultural reasons). Ultimately, we had to rely on gatekeepers and fieldsite visits to get in contact with the panel survey sample.[16]

Another challenge was the sensitive nature of some of the topics and themes of interest to the PDE project. For some survey questions about assets, debts and aid, answers were likely over- or understated, something which became clearer when doing the qualitative interviews. This may be have been because of confusion over our identity and the assumption that we might be able influence donors. For example, household assets, including remittances and NGO-related support, were likely understated in the survey, based on what we were later told in qualitative interviews. Embarrassment, potentially, also means that some participants declined to answer some questions, particularly about debt(s). Meanwhile participants were often keen to tell us about issues they faced that we did not directly ask about in the survey, such as the distances involved in fetching clean water and the lack of girls’ schools in Haripur.

Despite the challenges faced, we collected data on a large sample of the population of our three fieldsites, which would not have been possible without the hard work of our research assistants and enumerators, many of whom used their personal connections to help us gain access to gatekeepers and community leaders in the field sites. In a PDE blog post (Aman & Jan, 2021) we provided some more immediate reflections on the first survey experience.

Quantitative methods – baseline and panel surveys

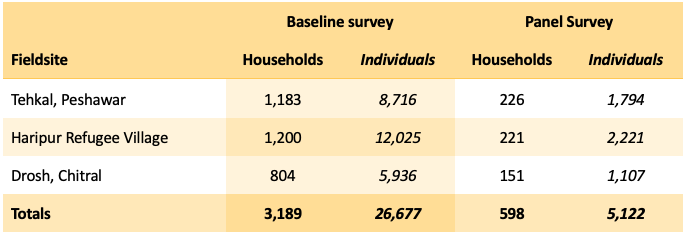

The baseline survey was conducted in late 2021 in Haripur and Peshawar, and the spring of 2022 in Chitral. The panel surveys were completed in all sites between April and June 2023. Table 2 provides the sample sizes for each survey, by fieldsite.

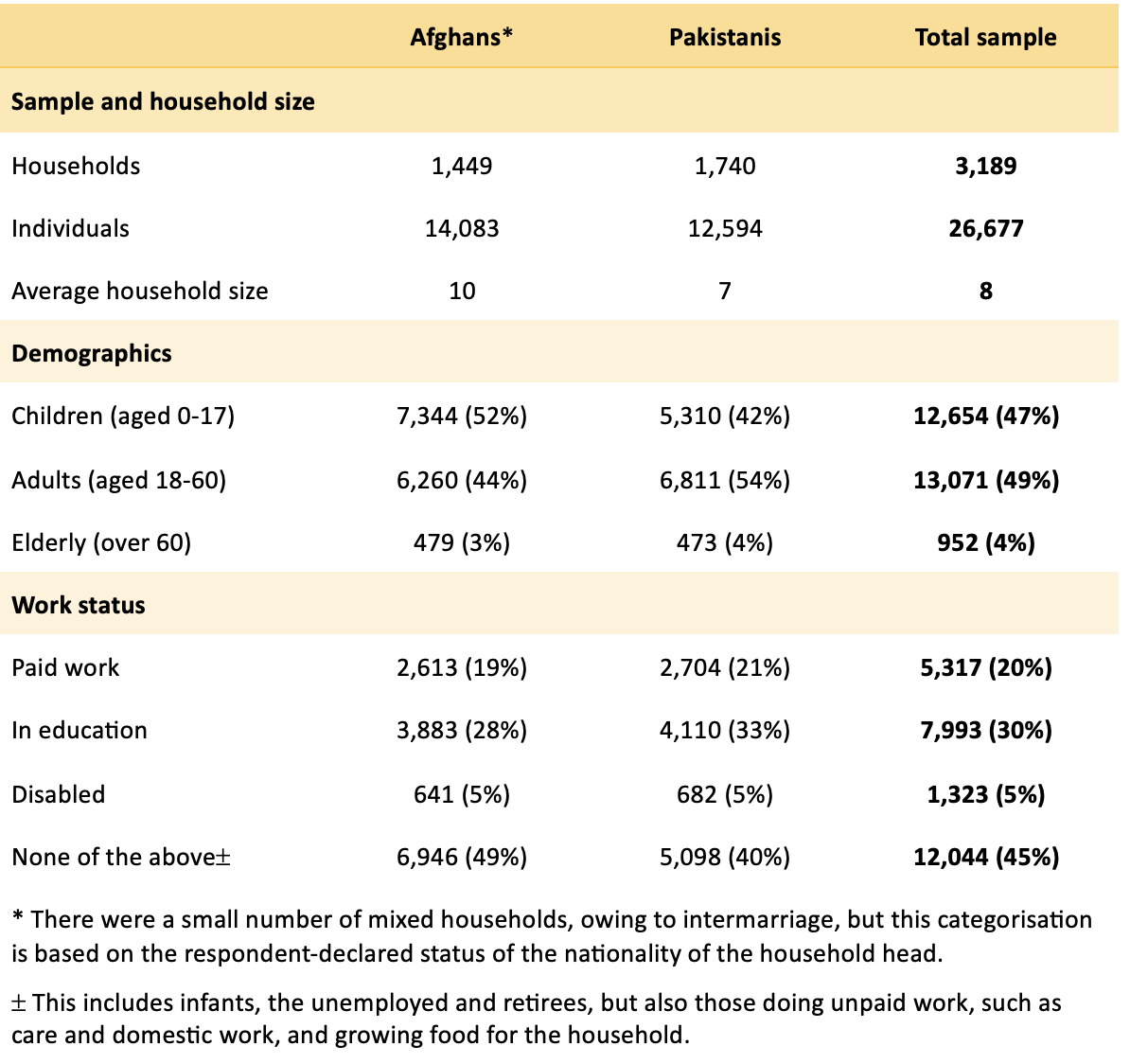

The proportion of female-headed households was extremely small, but in terms of survey respondents (answering the survey on behalf of their household) we managed to include 33% women in the baseline survey and 38% women in the panel survey. Of the 3,189 households surveyed in the baseline survey, 1,449 (45%) were Afghan households. Household rosters were conducted in the survey, and Table 3 gives some headline demographic data and work statuses for the individuals in households.[17]

At the aggregate level, the similarities between Afghan and Pakistani households are quite striking. However, there are some differences. Afghan households tend to be slightly larger, and consequently more likely to contain a larger proportion of children, and Afghan individuals are slightly less likely to be in work or education. Perhaps the biggest difference is education where, despite the Afghan sample representing 10% more children than the Pakistani sample, 5% more of the Pakistani sample are in education. These differences were confirmed by fieldwork observations and qualitative data collection.

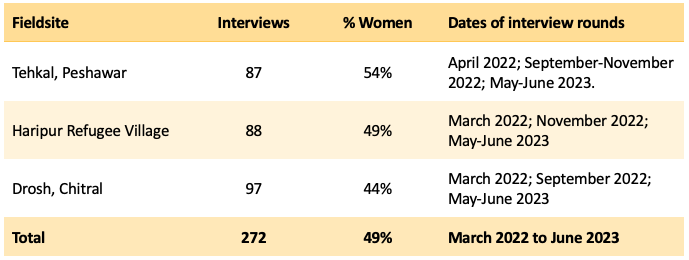

Qualitative methods – interviews and focus group discussions

A total of 281 qualitative semi-structured interviews were conducted across three rounds, completed in 2023, of which 49% were with women. Table 3 shows the sample sizes by fieldsite. Most interviewees were people who had also been participants in the survey, or members of surveyed households.

Twelve focus group discussions (four female, eight male) were held, to further discuss issues raised in the surveys and interviews. Four were held in each fieldsite.

Interviewees were asked if they were willing to participate in follow-up interviews and a small sample (three women, six men) of those who agreed were chosen to participate in more in-depth oral history interviews. These participants were chosen by a sub-committee of PDE researchers from across the partner countries based on a combination of factors, including the participant’s story-telling abilities, their life situation, and our efforts to reflect a mix of locations and experiences. These interviews will form the basis for long-form narrative accounts of people’s experiences of being part of a displacement-affected community.

Production of documentary films

The 10-day filmmaking workshop taught by Dr Yasmin Fedda was held from the 26 April to 5 May 2023 in Islamabad, with filming taking place in and around Peshawar. Six emerging filmmakers (three women, three men) were selected after a competitive application process attracted over 30 applications, predominantly from the Peshawar area, but also from Quetta, Lahore and Islamabad. The successful participants were chosen on the basis of a mix of skills and experience; five were Pakistani and one was Afghan.[18] None of the participants had professional filmmaking experience, but one was a wedding photographer (stills photography), three were studying journalism and therefore had some experience making short films for coursework, and all had been involved in making short films on their mobile phones for vlogging and/or TikTok, Instagram, etc.

In teams of three the filmmakers made two films, summarised in Figure 2. Both films movingly represent key themes of the PDE project. In Comrade Obaid (Zeb et al., 2023) a young Afghan talks about how he’s made a living, supporting his family; but also his frustrations at not having the same rights as Pakistani citizens, and how that – combined with family responsibilities – means he misses out on the opportunities his Pakistani peers might have. The Labour of One’s Own Hand is Beautiful (Nisar et al., 2023) illustrates how an Afghan man can have a successful business, employing both Afghans and Pakistanis, but cannot own it himself, because he is not a Pakistani citizen.

The Labour of One’s Own Hand is Beautiful

A film by: Zala Nisar; Ihteram Khan; Wasiullah Khan

The coal industry in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, is a site of economic activity and migration. An Afghan businessman works in partnership with his Pakistani friend and creates labour opportunities for locals and Afghan refugees alike, despite not being able to own the business himself.

6:47 minutes; Pashto and Dari with English subtitles

Comrade Obaid

A film by: Atif Zeb; Khush Bakht; Roshana Waqas

Obaid is a teenage jack of all trades. Coming from an Afghan refugee family living in Peshawar, he navigates the challenges of being outside his homeland, supporting his family, and finding a sense of belonging.

6:13 minutes; Pashto and Dari with English subtitles

Stakeholder engagement

Throughout the project, we worked closely with relevant stakeholders, both formally and informally. These stakeholders included civil servants working in CAR and other relevant departments, NGO representatives, community organisers, maliks, elders, religious representatives and camp officials (see also ‘Displacement-affected communities’ below). Our two largest public-facing events were international conferences on the theme of protracted displacement in Pakistan held in May 2023 and May 2024. At these we were able to share findings from the project, including showing the documentary films. An interesting aspect of this was showing selected films from other countries in the PDE project and discussing their similarities and differences with those made in Pakistan. We also held smaller stakeholder meetings at key stages of the project: prior to fieldwork whilst we were developing the survey and interview questions, and later on to share initial findings for feedback and discussion, and to present more formal analysis of our findings. Throughout the project, we had less formal discussions with stakeholders as part of the ongoing negotiation of access to research participants and fieldsites.

Key findings from Pakistan

Displacement-affected communities

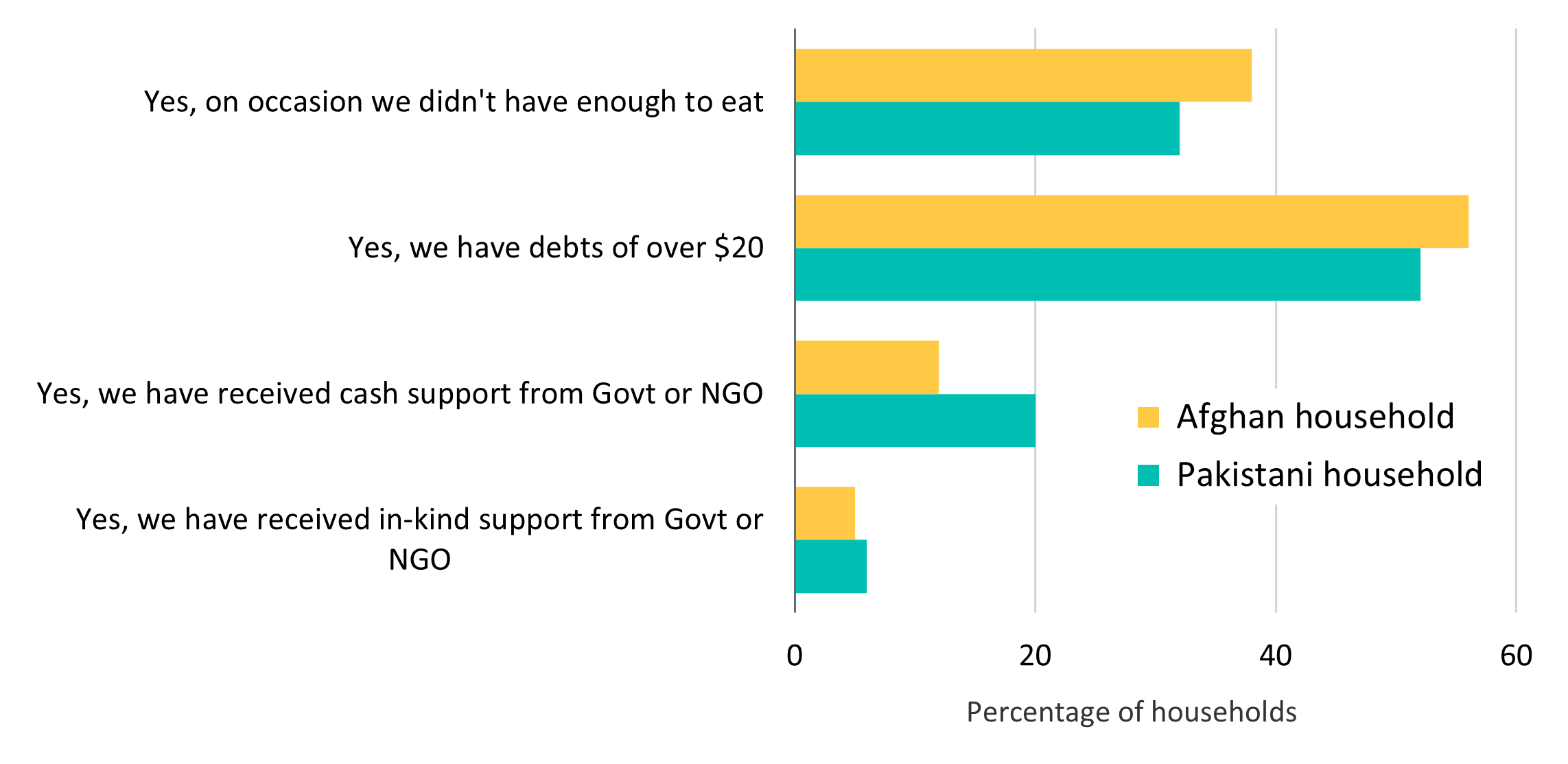

Our baseline survey demonstrates the relatively similar experience of marginality and precarity amongst both Afghan and Pakistani households in our fieldsites. For both sub-samples, around a third have not had enough to eat on occasion in the previous year; just over half are currently in debt; and only a tiny proportion have received any support from a government or non-governmental organisation in the previous year (see Figure 2).

Alongside these similarities of experience of precarity, the clearest socio-cultural indication of a displacement-affected community, rather than separate ‘hosts’ and ‘refugees’, in all three fieldsites, is the institution of gham khadi. During times of gham khadi, neighbours will provide food and sometimes money, often labour (e.g., childcare or preparing food), as well as emotional support. It was evident in all our fieldsites and often brought up as an example of good neighbourly relations – participation in gham khadi was seen as a defining feature of a good neighbour. Conversely, not participating in gham khadi was seen as an indicator of a lack of integration between groups.

Gham khadi creates a social network that nourishes the bonds of solidarity across the refugee-local divide. All the residents of a locality attend gham khadi and support each other emotionally, materially (money and food), and physically (through the provision of labour). The participants of gham khadi include not only relatives, neighbours, friends but mere acquaintances and co-workers from near and far. Interestingly, these occasions blur the boundary, even if temporarily, between host and refugee and create a bond of solidarity and care. Gham khadi provides a platform through which brother/sisterhood, solidarity and humanitarianism are carried out. The concept of gham khadi is anchored in cultural and religious principles and narratives. It also establishes the principal of reciprocity and mutuality. This is an area where the broader themes of the PDE project clearly intersect.

The protracted nature of displacement from Afghanistan to Pakistan means that although the role of UNHCR and other refugee-related authorities (particularly CAR) are still significant in some ways for some people, international humanitarian actors are not a major influence or contributor in people’s day-to-day lives. It is, perhaps, more important to think about the so-called ‘informal’ authorities (including social structures and hierarchies) that shape displacement-affected communities. There are certain intermediaries in all three fieldsites who are situated within and between the authorities and the displacement-affected communities. Some prominent intermediaries identified in our fieldsites include mesharan, maliks, elected representatives, social welfare actors, community mobilisers, landlords and aristocratic landlords (in Chitral). These intermediaries provide social and political leadership that is activated to settle disputes in communities, to mobilise people for social support in times of crisis and, in the case of maliks and mesharan, to provide the much-needed sense of belonging to a clan or tribe in situations of uprootedness and displacement. There is also some indication in our qualitative data that they act as intermediaries to connect refugees and their goods and services to the informal and formal markets. These entities are institutionalised historically through cultural norms and social practices.

These intermediaries also serve as channels through which authorities such as government institutions, INGOs and NGOs negotiate and manoeuvre their way to reach out to displaced people for the provision of aid and other services. Many of them are also key gatekeepers and stakeholders for researchers, including us. Despite the multifaceted role played by these intermediaries, their authority is also contested due to controversies related to their effectiveness in displacement settings; we observed this in Chitral and Haripur. In Chitral, both camp and city intermediaries are under fire; some are considered corrupt and/or inefficient. The more influential maliks are more vocal, have better resources (financial and social capital) and are closer to the authorities. Maliks in the camps are linked to the camp authorities via a ‘community mobiliser’ facilitated by CAR, who tries to balance the needs of the communities and the authorities. In the city of Drosh, Chitral, some of the most influential intermediaries are also the Shahzada (landed aristocrats), as are the landlords in Tehkal, Peshawar.

As discussed in ‘Regulatory frameworks for Afghans in Pakistan’ above, sociocultural and economic interlinkages between Afghanistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa are long-standing. There are some interesting findings relating to marriage across the three fieldsites. Intermarriages between Afghans and ‘locals’ are more prominent in Chitral than in the other two sites, which is perhaps surprising because Afghans – predominantly Pashtun – are ethnically different from Chitralis. However, they have integrated well through learning the local language, attending schools outside the refugee camps, and developing work-related friendships. Our qualitative interviews suggest these marriages are mostly Afghan men marrying into so-called ‘lower class’ Chitrali families. Some poorer Chitrali families think that hardworking Afghans will provide well for their daughters. However, respondents reported that some of these marriages were love marriages. There are also instances where Afghans have married into families where they had familial relations before their migration. Many Afghans in Chitral were previously living close to the border on the Afghan side, unlike in Haripur, where Afghans have covered long distances to reach Haripur.

Very protracted displacement has also created opportunities for economic integration within the displacement-affected community. Previous research already suggests Pakistan’s construction and transport sectors have heavily benefitted from migrant labour, including Afghans (Grare & Maley, 2011; Margesson, 2007), particularly in the physically demanding labour of manual handling of construction-related work and the loading and unloading of vehicles in fruit and vegetable markets (Collective for Social Science Research, 2005, 2006). Other more recent studies suggests Afghans’ major contribution in cultivating and irrigating agricultural lands that were once barren, thereby contributing directly to reducing food insecurity in the country (Baloch, 2022; Notezai & Baloch, 2022), something confirmed by our interviewees.

Whilst socioeconomic integration is high, political integration (and formal financial integration) faces many structural barriers (see also ‘Regulatory frameworks for Afghans in Pakistan’ above). Access to banking is severely restricted, and our data suggests that this also restricts remittance transfer through formal channels, leaving those receiving remittances from abroad, or sending remittances to Afghanistan to rely on hawala or hundi money transfer mechanisms. Our research confirms that refugees’ economic contributions are predominantly in the ‘informal economy’ because of the significant constraints to their involvement in the formal side of the economy. Refugees have created niches in agricultural and economic activities. In some specialised sectors, they have carved out a particular function, such as butcher shops, bread making, soup stalls, Afghani burgers and others. Often the knowledge they used to do this was developed during previous experiences in Afghanistan. Their contribution to the agricultural sector in all three sites stands out. They are working to cultivate land via informal land tenureship arrangements, or as daily wage farm workers. In all the three fieldsites, Afghan refugees have been cultivating locally owned land for generations.

Afghan participation in economic life has, however, also generated tensions with the ‘locals’. Our qualitative data suggests Pakistanis, especially from the urban and peri-urban sites of Tehkal, Peshawar, resent the economic penetration of Afghans in businesses. Therefore, there is a veiled (and at times open) criticism towards Afghans seen to be taking over businesses, especially in urban spaces. However, being Afghan and not having access to legal residency status also disempowers them in workspaces, restricting access to professional employment and formalised business ownership.

Feminist economies and mutual aid

Feminist economics challenges us to consider the role of the many labours and activities that support social provision and social reproduction, alongside the creation of economic capital via paid labour (see PDE Project, 2021a). The following quote from an Afghan man in Haripur Refugee Camp gives an indication of some of the activities we investigated in relation to feminist economies and the linked concept of mutual aid (see PDE Project, 2021b):

One of my brothers who died before migration had a son. I raised him, arranged his marriage, and currently, I am supporting him along with his children. A few days ago, he had a medical condition, in which he had to go through surgery. He is a poor person, having no money for food. The cost of his surgery was Rs. 40,000 [US$140]. Then I arranged another doctor for him in Haripur who did the same surgery at the cost of Rs. 20,000. I gave him Rs. 10,000 and the rest was arranged by my [other] brother.

This man’s household’s care for his nephew (or de facto son) and his children, both in terms of raising him but also supporting him in adulthood, is an example of mutual support within a family. Below, we give further examples of this kind of support both within families and tribal/clan groups but also between neighbours and friends, including those that cross nationality-based identities (Afghan-Pakistani).

Women’s work

In both Pakistan and Afghanistan, public space, and thus paid work outside the home, is heavily male dominated. Our qualitative and quantitative data suggests that gender and socio-economic position intersects with refugee identity to make life particularly challenging for Afghan women. Culturally and socially, most of the care work is women’s domain, and Afghan women are also even more culturally restrained than Pakistani women and Afghan men when it comes to seeking employment outside the home. The vast majority of the work women do is unpaid labour, but we did find some examples of paid work, predominantly inside the refugee camp fieldsites (Haripur, and Kessu and Kalkatak in Chitral).

Inside the camps, some women are generating small incomes through home-based artisanship or crafts, such as sewing clothes, embroidery, quilt-making, wool weaving, and in some parts of the camps, carpet weaving. Women face a disconnect between their skills (sometimes imparted by NGOs) and potential middlemen, and the market. Whilst a small number of refugee men in camps did have bank accounts, none of the women did. Whilst there are some women appointed by CAR as community mobilisers in the camps, their refugee status intersects with their gender to make them vulnerable to harassment from their Pakistani male supervisors, and some interviewees suggested this was particularly the case if they had to report to them outside the camp in offices located in cities and towns.

Our qualitative and quantitative data suggests that mental health issues abound for Afghan women. This has knock-on economic effects as health-related expenses are a major cause of debt. For Afghan women in our survey, 57% of those in debt cited health and medical reasons as their main reason for going into debt. This is particularly evident in Haripur, where 69% of indebted households said health-related expenses were the main reason for going into debt.

Despite these challenges, women are contributing to local economies, sometimes indirectly, in addition to the more obvious contribution of caring and domestic work that enables other household members to engage in paid labour. In all our fieldsites small home-based work, such as preparing food to be sold by their male relatives, is most common. In the Uzbek area of Haripur Camp, women’s higher end skills such as carpet weaving are visible. In urban areas, some Afghan women also operate their own beauty businesses in bazaars. Some women also work in low-level jobs in NGOs, IGOs or as teachers at local, mostly camp, schools. Our qualitative data suggests some NGOs have offered trainings to women to start home-based work (sewing clothes), but such opportunities are sparse and usually do not come with either the tools to continue the work or with training in the skills needed to connect participants to local markets. Research participants also complained of a lack of market awareness from the NGO facilitators as to what goods and fabrics would be saleable in their local contexts.

Mutual aid and support

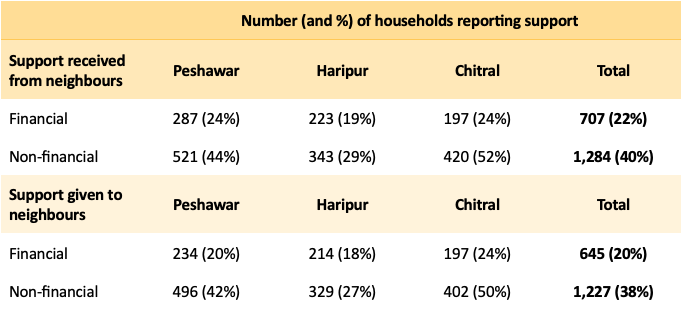

Our research shows the importance of neighbours as the main source of support within displacement-affected communities, alongside relatives and shopkeepers (these categories are not necessarily mutually exclusive) across all three fieldsites. Table 5 shows the numbers and proportions of households in our baseline survey that report giving and receiving support from neighbours over the last five years. The non-financial support (primarily food) is around double that of the financial support, and the figures suggest that at the aggregate level, at least, giving and receiving is reciprocal.

Conversely, support from organisations such as NGOs is low (and primarily financial), and survey respondents who received it were predominantly from the ‘local’ Pakistani population, rather than displaced people. Both financial and non-financial support is predominantly irregular (in terms of timing), whatever source it comes from.

The qualitative data from Pakistan shows that there is considerable evidence of mutual aid and care in all the sites investigated in this study. These instances of mutual aid and care are multiple and varied. Our interviews suggest that one of the most significant mechanisms by which reciprocal support is practised between neighbours and friends is through the activities related to gham khadi (see also ‘Displacement-affected communities’ above). It may seem odd to refer to such occasions as a source of mutual support, and we suspect it was not always ‘captured’ as such in the quantitative data, but the frequency at which they happen means they are a significant part of reciprocal community support and sharing of resources. Mutual support is extended almost mandatorily on these occasions in all three fieldsites. Providing food is most common but in relation to Afghans’ funerals, especially in Haripur, clan members will also collect cash contributions to help the aggrieved family and to cook and distribute food on a large scale for the guests gathered for condolences.

A young man in Haripur describes aspects of gham khadi, as well as mutual support more generally:

People support each other in many ways. Mashallah, the people living here are ghairati khalaq. In marriages and in times of grief, people support each other thoroughly. Additionally, in all sorts of crises, people support each other…

Similar activities are described by a woman in Peshawar:

We sometimes ask [our neighbours] for some household items such as tomatoes etc. And they do help us. Similarly, Mashallah if they need our help, we do cooperate with them. Besides, on the occasion of joy or sorrow, we offer our help to each other. We bring them tea or a meal. Similarly, they also come to our house and help us.

And a man in Chitral:

People do support each other. They help each other in burying the dead. For three days they provide food for the guests of the bereaved family. It is our custom… In weddings, people do the same. They are one [united] in gham [sorrow] and khadi [joy].

And many others expressed similar sentiments. In some parts of Haripur refugee village and the urban area of Drosh, Chitral, social welfare organisations have been set up to collect regular small monthly contributions from every family in the neighbourhood for spending on such occasions. Support is not limited to the provision of cash or food but also includes physical labour provided by men and women on such occasions, such as meal preparation and grave digging. For the most part, the younger members of the clan or neighbourhood would attend to the guests, cook a meal on a larger scale inside or outside homes, and prepare guesthouses for people coming to give condolences from outside the neighbourhood. An Afghan man in Haripur explained the cultural requirements and expectations associated with a death, as follows:

In this camp, most of the people live in their clans. For example, the Utmankhel tribe lives in this camp near my house. They are from Nangarhar [eastern Afghanistan]. There are about 400 families of the Utmankhel tribe living in this camp. They manage their funerals and marriages collectively with unity. In the case of gham [sorrow], their tribesmen collect the money and serve the guests and relatives of the bereaved family. They provide food and space to the guests. They also help each other in other matters, like in case of an emergency or illness but that is not done in an organised [formal] manner.

However, these kinds of support do not just occur within tribal groups. A man living in Drosh, Chitral, explained how help was given and shared between Afghans and Chitralis:

We help each other both physically and in terms of finances as well. We give financial support, according to our capacity, to those who need it for arranging gham khadi events. We also take food items for them when we visit. Sometimes we buy them rice and oil and sometimes we buy them sugar… We go to the graveyard and help in making the grave for the departed soul. We also serve their guests in the hujras [male guesthouse and gathering space]. We bring meals for the guests… we visit patients and ask about their well-being. We take fruits with us. We have this kind of relationship with Chitralis.

These networks create bonds of solidarity across the ‘refugee-local’ binary because the residents of a locality provide support to each other based on their spatial proximity and sense of neighbourliness. Support is also provided from those further afield, but this is sometimes limited. For example, people from outside the neighbourhood or clan often attend gham khadi gatherings without bringing any food or cash – they provide emotional support on such occasions.

Participating in gham khadi is an indication of the integration of neighbourhoods and communities and interlinks with support of other kinds, as illustrated by this Afghan woman interview in Peshawar:

Well, they [the neighbours] are very good. Some time ago, the son of the landlord warned us to vacate the place [house]. I along with my daughters were crying about what could happen! Though I knew this neighbourhood, I was worried… but they helped me! I am surrounded by Pakistanis mostly. I am familiar with them and participate in their gham khadi.

Other types of mutual support come from a shared history and experience of displacement. We observed many examples in relation to new arrivals from Afghanistan after the Taliban regained power in August 2021 who were supported and often housed by Afghans who had been in Pakistan for much longer. This was particularly the case in the Haripur fieldsite, which has seen many recent arrivals since 2021. One woman in Haripur camp described how she had helped new arrivals, and it had given her pause for thought as to what her family had achieved since arriving in Pakistan.

There are many families who have migrated just recently from Afghanistan… I am sure you will cry at their condition. They have nothing to eat here. We gave them household items. We have been trying to help them somehow; they have come here with literally nothing. Many of these families have no way to work or earn… So, looking at them we have been feeling grateful that thankfully we have got something to earn our bread and butter here at least.

We also observed examples of Afghan refugees helping Pakistanis who had been internally displaced, as a man displaced to Peshawar described:

A person who happened to be my cousin from Kandahar [Afghanistan] and living in Hayatabad [Peshawar] brought carpet and mattress for beds and other things to our home because he himself went through this experience of being a refugee… There was another friend who brought all the foodstuff in a vehicle and put it in front of our house.

Within displacement-affected communities, even those with very limited financial resources found ways to provide support in other ways, for example via access to land or firewood. An Afghan man in Chitral told us how people in Chitral had provided vital support, despite not having much to give:

These people are very poor people themselves. How would they support us? We are still thankful because they allowed us to collect wood from the mountains they own. They had nothing to offer us. At the very beginning they would offer us food when we came to the camps. But they have no money and limited resources so they could not offer much. We have taken their timber and grazed the grass, and they have never objected to that. We still do that.

The shared history and familial ties that cross the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan explain some of the empathetic feelings between Afghans and Pakistanis despite some of the tensions outlined above in ‘Displacement-affected communities’.

Mutual support via loans

Mutual support is also very prominent in the form of people providing loans to each other. Both qualitative and quantitative data refers to mutual support provided through debts in times of crisis. Friends, relatives and shopkeepers provide loans often without setting the date of repayment, and largely interest-free. Eighty percent of debts reported by households were owed to friends and family; only 5% of survey respondents had ever taken out a loan from a formal financial institution. Many research participants told us that they themselves are owed money, often for more than five years, but they know that their debtors are not able to repay them, and that that will continue for an unknown period. Despite this they do not press them for repayment. The rationale from the lender is usually that these people are unable to return the debt, and it is unethical to demand repayment. However, such concessions also bind the debtors to the lender in a moral bond. These kinds of mutual obligation towards each other (lender-debtor) require care and mutual support because both parties strive to survive through a patron-client bond. The lender cannot lend more if the debts are not returned, and the debtor cannot get more debts in the future if this bond is broken.

Financial debt and loans can also intersect with other forms of capital and labour, such as unpaid or in-kind work and repayment, as illustrated by a woman interviewee in Chitral:

We have many Afghan immigrants living side by side. We ask them to come and help us out in our daily household work. For example, during some family celebrations, mostly women come to our families. Even their men come and help us in timber logging. On the other hand, if they need any financial help, we try to support them. If they need any money, household items or clothes, they come asking for help and we help them. It is not that they come every day, it is when they need help in a week or a month.

Despite the leniency given by many lenders, it is also recognised that eventually debts should be repaid, and social pressure in the form of reminders is eventually applied to the debtor, as an Afghan shopkeeper in Haripur described:

The majority of them pay their debts, we give them time and do not press them to pay in that interval of time, but for those who do not pay [for a longer period], we remind them again and again, nothing more. Some people have been in debt to me for years. The range of the debt varies. It ranges up to Rs. 25,000 and Rs. 30,000 [US$85-120]. In the case of [borrowing for] weddings, it reaches one lakh even [US$350].

There was awareness that some debtors simply could not afford to repay what they owed, at least in the near future. As an indebted interviewee in Chitral explained, ‘There is pressure [from lenders] but they know we are helpless, how can we return money when we have barely enough to eat?’ The expectation is that when debtors do earn or otherwise gain some money, they will service the debt to the extent they are able. Of course, problematic indebtedness was also very visible in our data, and that is discussed more in ‘Sustainable economies in displacement-affected communities in Pakistan’ below.

Like non-financial support, loans do occur across familial and tribal affiliations, as a man in Haripur explained,

Yes, they [friends] do help each other. Of course, as I told you my friend is Kharoti by tribe. He is from Kunduz, and I am from Samangan, but we are friends. He sends me money whenever I need it. I will repay him the Rs. 500,000 [US$1,740] he gave me as a loan. He gave it to me for my child’s education and marriage.

They are also given between Afghans and Pakistanis, as an Afghan businessman in Chitral explained:

Alhamdulillah, with the local people we have a very good relationship… I don’t want to mention all kinds of support I give to the local community [Pakistanis] because Allah won’t like it. However, whenever those people [Pakistanis] need any help, the locals look towards me, and I do it happily. Last night, one of my best friends who is in Qatar, his mother came to me and asked me to give her Rs. 30,000 [US$100] because she needed it. So, in the morning I went to her and gave her Rs. 30,000 and told her to return it whenever she found some extra money. We have a very good relationship with the locals. In the same manner, they also give us loans.

However, as another man in Chitral explained, different types of relationships result in different types of repayment relationships:

There are Afghan shopkeepers who have big shops. We have borrowed from them… People have borrowed from Pakistanis as well. But I have personally borrowed from Afghans. They give you more time to return the debt… When I earn Rs. 1,000 [US$3.5], I spend Rs. 500 rupees on family and return Rs. 500 to the shopkeepers.

It is interesting to note that even in conditions where the entire neighbourhood is very poor, the lending of money continues. Even a small amount of money lent amplifies in value and serves as a good example of mutual care. In a very poor neighbourhood of the Kalkatak Camp in Chitral, one interviewee said:

If there are three to four people in a family who work, then such families can usually afford to lend small amounts of money to others. But those who have [only] one member to work, may not. Also, people lend you small amounts. They do not give you hundreds of thousands to invest in businesses.

Even if someone is in debt themselves, they may also lend smaller amounts of money to others in times of need, as a man in Haripur, who had told us he was in debt to the sum of Rs. 1,700,000 (US$5,900), said: ‘Yes, if someone asked for money and I have money available I may give him Rs. 2,000 or 3,000 [US$7-10].’

As discussed above (see ‘Feminist economies and mutual aid’), a key reason for taking on debt is health-related crises; lending money for medical expenses is just one way that mutual support is evident in health emergencies; other forms include providing references, accompanying sick people to hospitals further away, and sharing medicines and other remedies where available.

Mutual support to gain access to work

Mutual support also takes the form of information regarding work opportunities and making relevant introductions to employers, as appropriate. Friends, relatives and neighbours inform each other about the availability of daily wage work in the labour market. Several respondents told us that they let their friends and relatives know whenever they see a relevant opportunity. This sharing of information is crucial in the types of economies where we conducted fieldwork. For example, respondents from Kalkatak Camp told us that when they are doing construction labour in Drosh and they hear that the construction contractor needs more labour, they quickly inform their friends and relatives in the camp: ‘Of course, if someone gets a work opportunity he may take along other friends from the camp if there is a need for additional labour, I would do the same.’ Respondents from Haripur Camp shared similar experiences.

Similarly, relatives and young friends help each other out by sharing information about migrating abroad for work and sending remittances back home. Several respondents in Haripur expressed that they were helped by friends and relatives to prepare to migrate abroad (predominantly to the Middle East and Europe). Mutual support extends beyond borders, and young Afghans who migrated abroad found much in common with young Pakistanis who had also migrated via the same routes. As an Afghan in Haripur explained, when he was in the UK he was closer to the people from Pakistan than other people from Afghanistan and he worked with Pakistanis in a fried chicken take-away shop. He is still in touch with his Pakistani friends in the UK and they encourage him to come to Europe again but he said he ‘couldn’t muster the courage to travel on those dangerous paths again’.

Sustainable economies in displacement-affected communities in Pakistan

Work and business relations in the displacement-affected community

Although formal work or business partnerships are rare (particularly in Chitral and Haripur) work-related networks are developed amongst and between Afghans and Pakistanis. These networks are essential to pass on information related to work, gain access to work and exchange goods and money. These networks may include buyers and sellers, landlords and tenants, co-workers, and debtors and lenders. Our qualitative data suggests such networks of relationship across boundaries: Pakistani/Afghans, Pashtun/non-Pashtuns and between different tribe and clan groups. Pakistani landlords will lease out their lands to Afghans for years, building a strong relationship that lasts decades. Despite some disagreements on the price set as an annual rent on the agricultural land, there are rarely serious conflicts amongst landlords and tenants.

In Chitral, agricultural lands have become more valuable since the arrival of Afghans. This is because Afghans regularly grow vegetables that produce more profit than previous land usage. These vegetables are also available to the Chitrali (Pakistani) population at a fair price, whereas previously vegetables were brought from areas of Pakistan further south, which was not only costly but sometimes impossible during winter because the main road was closed. Similarly, the formerly barren or unused lands near the camp of Haripur and in the outskirts of Peshawar were made into productive arable land by Afghan refugees over decades. These Afghan labourers enabled the growing of crops such as wheat, corn and vegetables. These activities often resulted in a close relationship between the Pakistani landlords and their Afghan tenants, which contributed to social and economic integration; friendships have developed across ‘refugee-host’ divisions. Similarly, co-workers in the labour market developed a sense of comradeship as well as competition. Co-working friends pass on information related to work opportunities, help negotiate wage with contractors, develop investment partnerships, and provide loans to each other in times of crises.

Afghan refugees from Haripur Camp work in construction-related labour in Haripur city and beyond. One such labourer who worked for a Pakistani family for some time shared his experience:

He [a Pakistani] told me that I was like a brother to them… Since then, I have been working for their family. They have a big family and every one among them calls me for their work. They keep me happy.

Often these networks do not remain strictly work related and they may grow into social relationships through friendship and intermarriages. These networks are reinforced and strengthened through the practice of gham khadi. Moreover, these networks are often used in relation to obtaining support beyond work-related matters. Examples from our data include a landlord in Chitral providing a reference to an Afghan so they could gain access to a government service; a Pakistani co-worker helping an Afghan co-worker to access a hospital service through a reference and get an approval for establishing a medical laboratory; and an Afghan businessman bailing out a fellow Pakistani businessman caught at a police checkpost near camp.

These networks indicate that there is economic integration of refugees in the host society. However, this does not mean that there is the same level of integration across all the sites, or that economic and social integration is always equally strong. In Chitral, social integration is higher than Haripur and Peshawar. Haripur Camp is still an isolated site inhabited by a huge Afghan refugee population, which is strictly controlled by camp authorities. Although there is some social and economic interaction with the Pakistani population living around the camp, most of the social interactions of Afghans living there take place within the camp. Moreover, despite some integration across the host-refugee division, the strongest bonds of network (clan, neighbourhood and friends) are still within the respective communities of (Afghan) refugees and (Pakistani) hosts. There are occasional doubts and apprehensions between communities and there is a clear expression of identity markers, such as ‘refugee’ and ‘local people’ in the everyday language of the displacement-affected communities.

Income, employment and social mobility

From the baseline survey, it is it is clear that employment, agriculture and rent are the top income sources for people in the displacement-affected communities we researched in Pakistan. Reported remittances were very low (less than 3% of households recorded receiving them). Although the qualitative interviews suggest this is an understatement, they also suggest that for most families any remittances received were a supplemental income ‘top-up’ in times of need or in response to a significant life stage event, rather than a substantial component of household finances.

Employment undertaken by respondents is diverse. It ranges from daily wage work (e.g., in farm work or construction) to skilled work, and in the case of Pakistani respondents, government work. There are limited opportunities for employment-related upward mobility for Afghans owing to a lack of appropriate education, issues in legal ownership of businesses and property, and dissipating public support in the context of protracted displacement and the government’s deportation discourse.

In Pakistan, the formal labour market is challenging for Afghans because of several factors related to their refugee status and identity. Firstly, the refugee-related humanitarian INGOs and NGOs sector, which employed Afghans in Pakistan in the 1980s, shrunk significantly after the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan. Now, even what limited formal employment there is in the camps (e.g., teachers and vaccinators at the BHUs) are increasingly being filled with Pakistani employees. Secondly, Afghans are denied government jobs, which are only open to Pakistani citizens. Thirdly, before the launch of the computerised smart PoR cards in 2021, Afghan refugees were not allowed to legally rent properties or businesses in Pakistan or open a Pakistani bank account.[19] Most affluent Afghan families consequently own properties and do business in the name of trusted Pakistani friends, colleagues or business partners. Relatedly, most remittances are sent through informal money transfer systems, such as hawala or hundi networks. Fourthly, the challenges of accessing good quality education[20] are an obstacle to Afghans gaining upward mobility, especially in the professional fields. Only around 7% of the Afghans surveyed were in professional high- or mid-level paying jobs, or low-to-middle-income technical, clerical support or skilled machine operating job categories (compared to 19% of Pakistanis in our sample).

Even in the so-called ‘informal economy’, which is where most Afghans are employed, we observed an increasing negativity and resentment felt by Pakistanis towards Afghans conducting small businesses (e.g., roadside stalls and other micro-enterprises), which is perhaps linked to the growing deportation discourse in Pakistan. A narrative of Afghans being willing to do ‘anything’ labour-wise, and having taken over small business niches that would otherwise be available to Pakistanis, was apparent in our qualitative data.

The possibility of onward migration

In the context of continued instability in Afghanistan, a hostile discourse and threat of deportation from the Pakistani government, and the lack of opportunities for upwards social mobility, it is not surprising that some Afghans (young men, in particular) are considering onward migration to the Gulf or Europe. An Afghan businessman in Haripur told us:

One of my nephews and my own son came to me and told me that I should send them to Europe because we are in a lot of debt, and we cannot repay it through other means. At first I refused but later I agreed.

He described the various agents who had demanded more and more money at various points of the journey, the new debts he had taken on as a result, and told us that ultimately his son and nephew’s journey to Europe had cost him Rs. 3 million [over US$10,000]. The options for regularised international migration are extremely limited (for both Afghans and Pakistanis), as a younger man in Haripur explained:

Yes. I am trying to go abroad through legal channels. However, if I cannot go there legally, I may think of going through illegal channels because my financial conditions are slowly deteriorating. My father is getting older, and I must provide for my family… I do have relatives in Europe. But it is difficult to get there these days. My father is well placed in Saudi Arabia, Alhamdulillah. He is asking me to join him there, but due to visa issues, I cannot join him right now.

In the qualitative interviews it became apparent that the people most likely to be actively considering migration further afield were educated young men who were frustrated about the disconnect between their educational achievements and future job prospects and earning potential. This was apparent amongst both Afghan and Pakistani interviewees, but was particularly felt by educated Afghans who knew that as they were not Pakistani citizens they would never be able to access the employment security (and related social respectability) of a government job.

Informality as an opportunity and constraint

Livelihood-related economies in Pakistan’s displacement-affected communities are operating predominantly in the so-called ‘informal’ sector. Therefore, people working in those economies are subject to both the advantages of relative flexibility, but also the potential of labour exploitation. This is not just an issue for Afghans but also for Pakistanis in the neighbourhoods we surveyed. However, for Afghans, their lack of legal citizenship compounded and intersected with their situation as inhabitants of marginalised neighbourhoods (see also the film ‘Comrade Obaid’, described in Figure 2). This put them in an unequal position when it came to negotiating employment and business; in relation to his experience of business-related negotiations, an Afghan man in Haripur explained that ‘because of our refugee cards, we’re subordinate to Pakistanis’. More generally, Afghan interviewees told us how their position meant they avoided disputes in business (and life more generally) wherever possible, as they knew that any legal proceedings would not be in their favour. Because Afghans in Pakistan are not allowed to own businesses and property (see Section 1.1.1), Pakistani friends and business partners lending their names to official paperwork were a necessity for business success. In the majority of cases, this was key mechanism of mutual support, but it does also create a substantial financial liability risk if there were to be a falling out between friends, for example.

Both Afghan and Pakistani interviewees were well aware of the power hierarchy their different citizenship statuses created, and that Afghans constituted an important source of cheaper, more pliable labour than their Pakistani counterparts, as a Pakistani man in Peshawar told us:

Well, the primary reason for hiring Afghan migrants for low-skilled jobs is that they demand lower wages compared to local daily wagers. Secondly, one finds it far easier to work with them as subordinates as compared to local people because they would never be in a state of challenging one’s authority, while local people are quite troublesome.

In the context of the recent economic downturn and rising inflation, particularly during and after the Covid-19 pandemic, the presence of Afghans as a cheap labour force (presumed to be undercutting local workers) has been an issue of public concern and debate in Pakistan, even whilst many still recognise the important economic contributions Afghans have made to Khyber Pakhtunkhwa since the 1980s (see also Alimia, 2022).

Conclusion

According to the World Bank, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in Pakistan has the lowest per capita income of the Pakistani provinces, and has clusters of extreme and relative poverty (Malaga Ortega et al., 2025; World Bank, 2013). The province’s location, bordering Afghanistan, means its communities have been significantly shaped by displacement from Afghanistan for over 45 years. Our data suggests that for most of our research participants, whether Afghan or Pakistani, their economic lives are challenging, and that mutual care and support – the sharing of resources, whether food, care, labour, information about job opportunities, or in some cases, money – is integral to their day-to-day survival. However, whilst both Afghans and Pakistanis in our fieldsites faced economic challenges, Afghans’ economic situations intersected with their political status as non-citizens, putting them in an inequitable position in relation to their Pakistani neighbours. Whilst this has a minimal effect on their day-to-day lives, it does have a substantial impact on their ability to plan and invest in their (and their descendants’) lives in Pakistan, which also affects their emotional well-being. At the time of writing, this sense of instability and insecurity has been made worse by the latest phase of deportations from Pakistan to Afghanistan under the 2023 ‘Illegal Foreigners Repatriation Plan’. These deportations interplay with an increasingly negative public and media discourse towards Afghans in Pakistan, in keeping with the anti-migrant/refugee public discourse in many countries’ contemporary domestic politics. Despite all these challenges, the presence of Afghans in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa has contributed to positive changes in relation to the introduction of new types of agriculture and business models (particularly around food production and transportation), and the contributions of Afghan labour to the development of cities such as Peshawar has been well-documented (see Alimia, 2022).

During various phases of the Afghan conflict, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa has received differential amounts of external resources and political interest from the international community, including significant amounts of humanitarian aid for Afghan refugees in the 1980s, and increased securitisation in the context of the post-2001 ‘global war on terror’ . However, the main sources of support for people affected by displacement have primarily been found between Afghans and between Afghans and Pakistanis. Afghans and Pakistanis in these displacement-affected localities cannot rely on consistent external assistance. At the time of writing, the presence of the international aid community in relation to displacement-affected localities in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa is minimal: of the over 3,000 households we surveyed, fewer than 20% had received any cash support from either an NGO or the Pakistani government in the previous 12 months, and this proportion would be even lower if not for the cash support some received following the Covid-19 pandemic.

There are long-standing Afghan refugee populations in Pakistan, and their socio-economic integration has been facilitated by ethno-linguistic similarities and solidarity between the predominantly Pashtun Afghan and Pakistani populations on both sides of the Durand Line. The shared cultural practices associated with gham khadi provide a significant way in which solidarity and humanitarianism are carried out in these displacement-affected communities, which are anchored in cultural and religious principles about what it means to be a good neighbour, operating in reciprocity and mutuality. Whilst initial support to displaced people in Pakistan might be shaped by cultural norms around hospitality, sympathy (and often, shared ethnicity/religion), ongoing support via the practices of gham khadi and neighbourliness smooth at least some of the challenges faced by those living in displacement-affected localities.

References

ADSP. (2018). On the Margins: Afghans in Pakistan. Asia Displacement Solutions Platform/DANIDA. https://adsp.ngo/publications/on-the-margins-afghans-in-pakistan/

Ahmad, W. (2017). The Fate of Durable Solutions in Protracted Refugee Situations: The Odyssey of Afghan Refugees in Pakistan. Seattle Journal for Social Justice, 15(3), 591–661.

Alimia, S. (2019). Afghan Refugees in Pakistan. Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. https://www.bpb.de/themen/migration-integration/laenderprofile/english-version-country-profiles/292271/afghan-refugees-in-pakistan/

Alimia, S. (2022). Refugee Cities: How Afghans Changed Urban Pakistan. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Alimia, S. (2023). Rethinking Durable Solutions in Peri-Urban Areas in Pakistan. Asia Displacement Solutions Platform/Samuel Hall. https://adsp.ngo/publications/adsp-expert-commentary-2-rethinking-durable-solutions-in-peri-urban-areas-in-pakistan/

Aman, S., & Jan, A. (2021). Reflections on survey methods in a refugee village in Pakistan. (November 16). Protracted Displacement Economies. https://www.displacementeconomies.org/reflections-on-survey-methods-in-a-refugee-village-in-pakistan/

Baloch, H. K. (2022, July 20). The Afghan refugees turning barren soil into fertile land in Balochistan. The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/asia/south-asia/afghan-refugees-agriculture-balochistan-b2125492.html

Barker, M. (2018). Pakistan’s Imran Khan pledges citizenship for 1.5m Afghan refugees. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/sep/17/pakistan-imran-khan-citizenship-pledge-afghan-refugees

BBC News. (2025). Afghans hiding in Pakistan live in fear of forced deportation. (March 3). BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cgl00ler0rno

CAR. (2018). Camp Wise Afghan Refugees Population in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Commissionerate for Afghan Refugees (CAR). https://www.scribd.com/document/551322320/Afghan-Refugees-Camp-Population-in-KP-March-2018 and http://kpkcar.org/images/docs/Afghan%20Refugees%20Camp%20Population%20in%20KP%20March%202018.pdf

Centlivres, P., & Centlivres-Demont, M. (1988). The Afghan Refugee in Pakistan: An Ambiguous Identity. Journal of Refugee Studies, 1(2), 141–152. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/1.2.141

Collective for Social Science Research. (2005). Afghans in Karachi: Migration, Settlements and Social Networks (Case Study Series). Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit. https://www.refworld.org/reference/countryrep/areu/2005/en/26999

Collective for Social Science Research. (2006). Afghans in Peshawar: Migration, Settlements and Social Networks (Case Study Series). Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit. https://www.refworld.org/reference/countryrep/areu/2006/en/9126

Dorronsoro, G. (2005). Revolution Unending: Afghanistan, 1979 to the Present (J. King, Trans.). Columbia University Press.

Dupree, L. (1973). Afghanistan. Princeton University Press. https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691643434/afghanistan

EUAA. (2022). Pakistan—Situation of Afghan Refugees: Country of Origin Information Report May 2022. European Union Agency for Asylum. https://euaa.europa.eu/news-events/euaa-publishes-report-afghan-refugees-pakistan

Ghobadi, N., Koettl, J., & Vakis, R. (2005). Moving Out of Poverty: Migration Insights from Rural Afghanistan [Social Protection and Livelihoods]. Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit. https://areu.org.af/publication/515/

Gopal, A. (2015). No Good Men Among the Living: America, the Taliban, and the War Through Afghan Eyes. Picador.

Grare, F., & Maley, W. (2011). The Afghan Refugees in Pakistan (Fondation Pour La Recherche Sratégique). Middle East Institute.

Gul, A. (2021). More Than 300,000 Afghans Flee to Pakistan Since Taliban Takeover of Afghanistan [News]. (December 16). VOA. https://www.voanews.com/a/more-than-300-000-afghans-flee-to-pakistan-since-taliban-takeover-of-afghanistan-/6357777.html

Haroon, S. (2007). Frontier of Faith: Islam in the Indo-Afghan Borderland. Hurst.

Harpviken, K. B. (2009). Social Networks and Migration in Wartime Afghanistan. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230234208

Hashim, A. (2018). Pakistan PM pledges citizenship to refugees. (September 17). https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/9/17/imran-khan-pledges-citizenship-to-afghan-and-bangladeshi-refugees