Unit 7 Children and Young People: SDG1

No Poverty

Goal no. 1 of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development aims to end poverty in all its forms everywhere.

Click on the arrows to reveal more information about SDG1. You don’t need to remember everything you read – the main thing is to get an overview of this Goal.

Information and targets reproduced under the terms and conditions of United Nations websites. Copyright (2023). All rights reserved.

A reminder that links in this e-book do not open in a new tab. If you click on any of the links to a webpage, click the back button in your browser to return here.

Key vocabulary

Check that you know the meaning and the whole word family of these key words before you begin the Unit. (NOTE: there may be other versions of the word forms – these are the common forms in the context of SDG1). Also notice some common collocations in bold in the ‘Why this goal? and ‘Targets’ sections above. Add any new words, word families or collocations that you would like to remember to your vocabulary book.

Verb Noun Adjective

To eradicate eradication eradicable

To be poor poverty poor

To nourish nutrition nourished*

To be vulnerable vulnerability vulnerable

To be deprived deprivation deprived

*undernourished, malnourished

Introduction

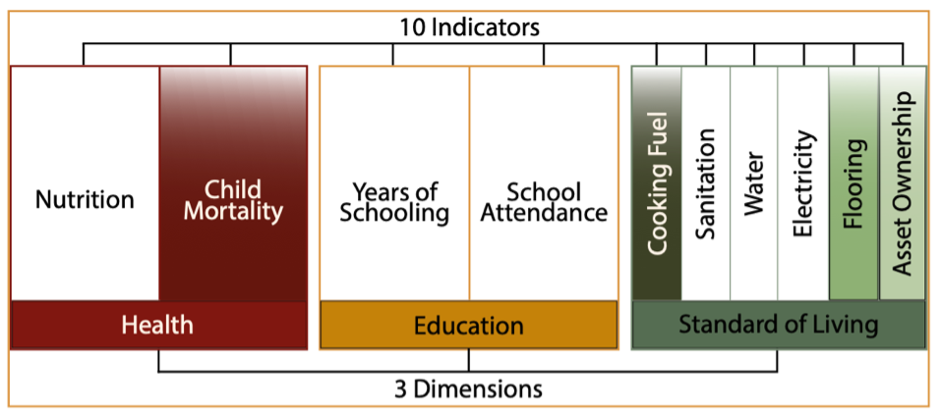

In Units 5 and 6 you considered the ways that various inequalities affect life opportunities for adults. In this Unit you’ll consider the life chances of children and young people. Children constitute half of the world’s poor. One in four children under the age of five, world-wide, has not grown to an adequate height for their age group. This demonstrates the levels of poverty and malnutrition that many young people live with. The global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) uses measures to assess deprivations in three dimensions of poverty in order to understand how health, education, and living standards intersect with one another and overlap, and to find out how many children are ‘multidimensionally poor’.

- What is your response to finding out that children constitute half of the world’s poor?

- Can you explain what the term ‘multidimensionally poor’ means (answer below)?

In your local context

- Which communities are multidimensionally poor?

- Is poverty or deprivation commonplace?

Data Visualisation – The global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI)

The MPI draws attention to ten indicators that affect children’s life chances that go beyond just income and reflect household features that shape children’s lives, such as whether anyone has five years of schooling. A person is identified as multidimensionally poor if they are deprived in one-third or more of the ten indicators. This captures how people experience different deprivations simultaneously.

- Read the infographic and answer the questions (Click the hyperlink in the title to see the infographic full screen).

- What are the 3 dimensions of poverty?

- What are the 10 indicators that affect children’s life chances that go beyond just income?

- How many indicators are there

- in the Health dimension?

- in the Education dimension?

- in the Standard of Living dimension?

Download Unit 7 Infographic transcript

2. Mari lives in Ecuador, South America, and is poor according to the global MPI. Read her poverty profile below and make notes about aspects of her life. Click on each section on the left-hand side, or use the blue arrow in the bottom right to move through the sections. Answers below.

Poverty profile: Mari, Ecuador

Mari lives with her family in a small town about a one-hour drive on a dirt road west of Cañar, Ecuador.

Mari, aged 10, is one of five children, of which four survive. She has a little brother aged 4, and two older sisters aged 16 and 17. All children have gone to school, and Mari is in 5th grade at a bilingual school.

Her family cultivates the land around their house for food but do not produce enough to sell, as they do not own much land. Her parents both go out to find work on other farms. But this is highly irregular. When they do work, they make about US$10–US$15 a day. In good times they find work about one week every month. The best estimate of the family income is US$675 a year.

Water, from a hose on an outside patio, is a short walk away, and Mari often helps by bringing it in. Mari lives in a house made of block with a dirt floor. She is interested in cooking and watches her mother in an outside kitchen. They cook with wood in a small rudimentary fireplace, but smoke does get in her eyes sometimes. Health care for children like Mari is now free at a health clinic in Shuya.

Mari’s house, like her life, is simple. It does not have a TV or radio or any electrical appliance. Naturally, they do not own a car or even a bicycle. The family is raising two head of cattle and two pigs for food although they are not in the best of health. She is especially fond of the family rooster and three hens. Mari is very quiet and shy, but from time to time a winning smile bursts through.

Profile, photo and infographic reproduced with kind permission from Alkire, S., Jindra, C., Robles, G. and Vaz, A. (2017). ‘Children’s Multidimensional Poverty: Disaggregating the global MPI’, OPHI Briefing 46, p. 7, Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI), University of Oxford. Copyright (2017). All rights reserved.

Reading – Growing up in poverty weakens later health – even if you escape it

Before you read

The text deals with the widespread problem of poverty. Does it surprise you to learn that in the UK, 30% of children are growing up in poverty? Or that more than half of these children are in households where one or both parents work, and poverty is on the rise even for children whose parents work in government-funded jobs? Is the situation similar in your context?

Read for main idea

In this text you’ll find out more about the link between poverty and health over the lifespan (the length of time that someone will live). Predict some of the things the text will say about this topic.

Scan the text (max 1 min) and see if your predictions were accurate.

Read for detail

Growing up in poverty weakens later health – even if you escape it

Poverty remains a widespread problem. In the UK, 30% of children are growing up in poverty. More than half of these children are in working households, and poverty is on the rise even for children whose parents work in government-funded jobs.

According to new research from the University of Geneva, these children may be at risk of poorer health in adulthood – even if they escape poverty later in life. This suggests that childhood adversity doesn’t just affect our choices, but also directly compromises the biological ability of our bodies to stay healthy.

Our childhood affects our health across the course of our lives. Stress, it seems, is a major contributor. While a life lived with financial, educational and social security and stability may not be free of worries, a disadvantaged childhood means more exposure to a number of difficult circumstances and events. These may include social tensions, domestic abuse, neglect, food and fuel poverty, unsafe or poor-quality housing, and separation from caregivers.

These life events understandably cause stress. Most of us will have personal experience of responding to pressure at work or a relationship breakdown with ice cream, cigarettes or alcohol, or giving the gym a miss. When facing financial troubles, the health benefits of vegetables can seem trivial to parents in the face of the time- and money-saving virtues of junk food. Feeling like you do not have enough food, money, time, or friends occupies the mind so that there is less space to focus on decisions with long-term pay-offs.

Experiencing these feelings over a long period of time (rather than the shorter-term stress experienced when applying for a job or studying for an exam) can make it increasingly difficult to make healthy choices. Over a lifetime, choices add up. But this latest research suggests that chronic stress impacts more than just our choices.

What doesn’t kill you makes you weaker

In the new study of over 24,000 people across 14 countries, researchers found that individuals, particularly women, of lower socioeconomic status in childhood had lower hand grip strength in older adulthood – a reliable health indicator, predicting the risk of frailty, disability, and death from cardiovascular disease and cancer in older age.

While health-related behaviours such as exercise, nutrition, smoking and alcohol consumption were partially responsible for this link, adults from poorer backgrounds had weaker grip strength even if their socio-economic status improved later in life. This suggests that a tougher start in life has a direct, biological and lasting effect on an individual’s ability to stay healthy.

We already know that children suffering from long-term stress build up higher levels of the stress hormone cortisol, making the body’s response to threats from the outside world change. Chronic stress in childhood is related to a host of diseases through mechanisms such as poorer mental health, changes in the body’s immune response to infection and injury, and increased blood pressure.

Now, we have evidence that growing up in poverty has a cumulative wear-and-tear effect on the physiological systems that govern how our bodies respond to our environment, permanently disrupting the ability of affected individuals to maintain good health in old age.

While more work is still needed to understand how early adversity affects our immune system and other physiological systems in later life, one thing is already clear. To make our society less stressed, happier and healthier, we need to recognise just how crucial a role hardship in childhood plays in determining an individual’s long-term health.

The argument that poverty and poor health are down to laziness or lack of willpower is itself lazy and too often thrown around. Poverty in early life affects not only how capable the mind is of making the right choices, but also how the body responds to adversity at a fundamental level. Far from being a resource drain, investing money in improving children’s quality of life could improve a range of health outcomes, and dramatically reduce the burden on a health-care budget stretched by the vast capital needed to care for older people.

Rock star Marilyn Manson got it right with the lyrics for Leave A Scar. What doesn’t kill you, in many ways, makes you weaker. Those who thrive amid deprivation do so in spite of, rather than because of, the difficulties they experience. Many less fortunate people will struggle to stay fit and well despite making healthy choices. We could do with providing them with a little more support, and a little less judgement.

NB This version of the article, with permission from the author, does not include the hyperlinks to supporting articles found in the original. Click the title for the full version of the text, published under a CC BY ND licence in The Conversation, which should be used for reference and sharing.

Grammar – Verb + dependent preposition

Read the 10 sentences from the text and note the multi-word verbs (verb + dependent preposition) in bold:

- Children are growing up in poverty.

- Children may be at risk of poorer health in adulthood.

- Their life may not be free of worries.

- Most of us have experience of responding to pressures.

- There is less space to focus on decisions.

- Over a lifetime, choices add up.

- Health-related behaviours were responsible for this link.

- A tougher start in life has an effect on our ability to stay healthy.

- Children suffering from long-term stress build up higher levels of cortisol

- Long-term stress is related to a host of diseases.

Infinitive form of the verbs:

- to grow up in (a particular way/state).

- to be at risk of (something).

- to be free of (something or someone).

- to have experience of (something).

- to focus on (something or someone).

- to add up.

- to be responsible for (something or someone).

- to have an effect on (something or someone).

- to build up.

- to be related to (something or someone).

Focus on verb + dependent preposition

Dependent prepositions are prepositions that depend on or must follow a particular verb. There are no grammatical rules to help you know which preposition is used with which verb, so it’s a good idea to try to learn them together. To help you do this, write new vocabulary in your notebook in a sentence or phrase.

Practice

Vocabulary – Adversity

The text deals with ways that poverty in childhood affects a person’s life chances across their whole lives, and that ‘those who thrive amid deprivation do so in spite of, rather than because of, the difficulties they experience’ (final paragraph). The verb ‘to thrive’ means that a child (or animal or plant) grows and develops well.

These words and phrases from the text are used to describe adversity, or things that make it difficult for a child to thrive. Match each term with the correct definition.

Pronunciation /æ/ and /ɑ:/

Hearing the difference between long and short vowel sounds, and being able to say them clearly, is one of the core pronunciation features which aid mutual understanding when a non-native speaker of English talks to another non-native speaker.

Focus on /ɑ:/ and /æ/

Long vowel sound /ɑ:/ e.g. hardship, start

- The most common spelling is ‘a’ (large, far) but there are others: heart, laugh.

Short vowel sound /æ/ e.g. had, adversity

- The most common spelling is ‘a’ (action, can).

NB There is variation in the way native speakers pronounce words containing these two sounds. The examples in this section do not vary, however.

Practice

Listening – Lockdown and young people living on the streets of Harare, Zimbabwe (4 mins)

![]()

Credit: The Conversation, Pasha 88. Ozayr Patel, Digital Editor. Licence: CC BY NC ND

Janine Hunter, Researcher, University of Dundee, UK; Lorraine van Blerk, Professor, University of Dundee, UK; Shaibu Chitsiku, Programme coordinator, Street Empowerment Trust, Zimbabwe

For many homeless young people living on the streets, lockdown and the COVID-19 pandemic made their situation worse. The city of Harare in Zimbabwe was no exception. Lockdown made it difficult for young people to find food and make money in the informal economy. Researchers set up a story map – a map with text, images and multimedia content – to hear children’s voices in three African cities: Accra in Ghana, Bukavu in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Harare in Zimbabwe.

In this Listening you’ll hear Janine Hunter and Lorraine van Blerk discussing the project, and Shaibu Chitsiku offering insights from Harare.

Before you listen

- Is homelessness a problem in your local context? Are many children homeless?

- Can you think of any reasons that might lead to children becoming homeless in Harare?

- Whose responsibility is homelessness?

Look at the word cloud created from the transcript. The most frequently used words (the biggest ones in the cloud) are: young (11), People (11), streets (9), food (7), lockdown (6). With the title in mind (‘Lockdown and young people living on the streets of Harare’) create a sentence that uses as many of these words as possible and predicts the main point of the listening.

Listen for main idea

Play the audio here.

(Or access The Conversation podcast and listen from the start to 4.25mins).

Listen to the introduction (0 – 1.36 minutes) then pause the audio and answer the questions:

- How many young people were involved in the project ‘Growing up on the streets’?

- What is the basis of the project/what do the researchers believe about young people?

- The researchers chose ‘story maps’ as a way of enabling young people to tell their own stories to global audiences. What are ‘story maps’?

Listen for detail

Before you listen to the rest of the podcast read the list of changes the young people experienced in their lives during the period of lockdown in the Covid19 pandemic. Play the rest of the audio and as you listen click any changes that you hear Hunter and van Blerk mention. You can stop and start the audio to give yourself time to do the task.

Download Unit 7 listening transcript

Research

Click the link to access the story map for the ‘Growing up on the Streets’ project. The project is in 10 chapters that look at a key aspect of life most important to street children and young people:

- Shelter

- Building assets

- Resilience

- Keeping safe in the city

- Health and wellbeing

- Support of friends

- Making a living

- Enough to eat

- Plans for the future

- Time to play

Choose ONE of the 10 chapters by using the buttons on the left-hand side of the screen and find out about the life of street children and young people by reading the information and watching the video. Write a short summary of what you found out (100 – 200 words).

Writing

In this Unit you’ve learned about the way poverty affects the life chances of many children and young people. In Allam Amin’s story we see him using his experience to support citizens in disaster situations and look after the health of displaced families in Indonesia.

Read Allam’s story and write a response to it that incorporates what you know about opportunities and life chances as they relate to SDG1 No Poverty. Write about:

- Allam’s experience as a child that led to him becoming a humanitarian worker.

- Life chances of children and young people who grow up in areas struck by natural disasters.

- Allam’s model of planning for disasters, and his efforts to deal with poverty.

- Any other topic relevant to the life chances of children and young people and SDG1.

‘I Know It Saved Lives’: What Growing up near an Active Volcano Taught One Humanitarian Worker about Preparing for Disaster

Allam Amin is a humanitarian worker who supports some of Indonesia’s most vulnerable people during emergencies and relief projects by coordinating logistics and supply chains for essential items like medicine, shelter and dignity kits. “I am used to disasters,” Allam says. “I grew up in eastern part of Indonesia and there was a volcano that regularly erupted.” When he was just a boy there was a major eruption that forced his family to flee. “I remember the panic in this small town,” he says. “The whole community moved to the next island all at once.”

Growing up near an active volcano when he was young, he dedicated most of his time after school to projects distributing medical equipment to regional health networks for emergency preparation. When a series of disasters hit Indonesia early in his career, Allam shifted to use his logistics skills in humanitarian response.

He explains that the health of displaced families shall always be the priority in a disaster response plan, and he abides to this principle at all times. The model of planning Allam worked on has been woven into national preparedness plans that support health districts across the country.

“We need to come up with the idea of working closely with counterparts and donors to make sure that this capacity is available any time of the year,” he says. Allam says a smart logistics system will have dynamic digital inventory that manages stock and storage with life-saving efficiency.

Department of Economic & Social Affairs Statistics Division (2022) ‘Bringing Data to Life: SDG impact stories from across the globe.’ Available at: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2022/SDG2022_Flipbook_final.pdf

Speaking – Poverty in America

- Work with a partner and choose one of the discussion topics available here about poverty in America. Click on the module you have chosen and read the information. There are additional resources on the right-hand side which you are welcome to watch/read/listen to as optional input. Discuss the information you find.

- Work in larger groups and share the information you have gained, and your response to it.

A reminder that if you have access to the internet and are studying by yourself without other people to practice your spoken English with, you can use artificial intelligence (AI) to gain fluency practice. See here for instructions and prompts.

Here is a prompt related to this Unit:

‘Let’s have a dialogue about the link between poverty and health. Tell me some of the effects of early poverty on a person’s health, and I will ask you some questions about it.’

Looking Ahead to Unit 8

In Unit 8 you’ll look at the levels of access to education that children have in various parts of the world and find out more about the lives of young refugees.

- Do you have refugees in your country?

- Where have they arrived from?

- Does your government make them welcome?

- Do their neighbours make them welcome?

- What is your view on whether countries should welcome refugees or not?

Use the menu bar on the left-hand side of the screen to access Unit 8