Unit 13 Food: SDG2

Zero Hunger

Goal no. 2 of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development aims to end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture.

Click on the arrows to reveal more information about SDG2. You don’t need to remember everything you read – the main thing is to get an overview of this Goal.

Information and targets reproduced under the terms and conditions of United Nations websites. Copyright (2023).

A reminder that links in this e-book do not open in a new tab. If you click on any link to a webpage, click the back button in your browser to return here.

Key vocabulary

Check that you know the meaning and the whole word family of these key words before you begin the Unit. (NB there may be other versions of the word forms – these are the common forms in the context of SDG 2). Also notice some common collocations in bold in the ‘Why this goal? and ‘Targets’ sections above. Add any new words, word families or collocations that you would like to remember to your vocabulary book.

Verb Noun Adjective

To waste waste wasteful

To be/to go hungry hunger hungry

To nourish/be malnourished nutrition nutritional/nutritious

To be secure security secure

Introduction

In this final section of Develop Your English you’ll learn about the links between climate change and health. In this Unit you’ll find out about food insecurity in both Africa and America. Food insecurity is defined as a lack of consistent access to enough food for every person in a household to live an active, healthy life, and is higher among particular groups of people.

In your local context…

- These are the four major drivers and underlying factors that affect food security and nutrition in the world. Which of these is evident in your local context?

-

- Conflict

- Climate variability and extremes

- Economic slowdowns and downturns

- The unaffordability of healthy diets

- According to the World Health Organisation, 2019 820 million people worldwide are still going hungry, and reaching the target of zero hunger by 2030 is ‘an immense challenge’. How evident is this challenge in your context?

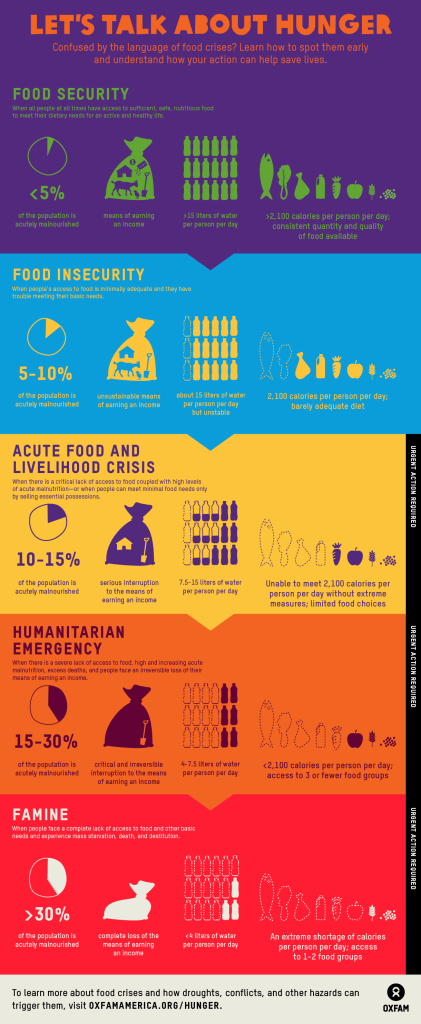

Data visualisation – Let’s talk about hunger

Read for main idea and for detail

Click here to see the infographic full screen.

Download the transcript here: Unit 13 infographic transcript

Reading – Ghana’s school feeding scheme is slowly changing children’s lives

Before you read – Prediction

- In this reading you’ll find out about a school feeding programme in Ghana, Africa. In which of the five sections on the infographic above do you guess the children and their families might fit in terms of food security?

- It’s easy to see why feeding hungry children leads to an improvement in their well-being, but can you predict why the programme also leads to improvements in educational attainment, and gender equality?

Read for detail

Ghana’s school feeding scheme is slowly changing children’s lives

Millions of Ghanaian children live in poverty. About one in ten – roughly 1.27 million – come from households that are so poor they can’t afford the amount and type of food that’s needed to stave off malnutrition.

Without proper food, children are prone to stunted growth or are underweight for their age. And their schooling suffers, too: research has repeatedly shown that children struggle to learn when they are not properly fed and nourished.

A school feeding programme introduced by the Ghanaian government more than a decade ago has gone some way to tackling the problem of hunger. The programme has reached millions of children – and it’s been proved to keep them in school far longer than their hungry peers. Now some more work is needed to make the project sustainable and to ensure it doesn’t constantly have to rely on donor funds.

Millions of children reached

The Ghana School Feeding Programme was initiated in 2005 by the country’s government in collaboration with the Dutch government. Its primary objectives are to increase school enrolment, attendance and retention among children in kindergartens and primary schools. It also, of course, aims to reduce hunger and malnutrition.

The programme started as a pilot project with ten schools, one from each of Ghana’s ten regions. This was later increased to 298 schools, reaching about 234,000 children in 138 schooling districts. In March 2016, it was reaching more than 1.7 million children every day – about 30% of all Ghanaian primary and kindergarten pupils.

Each day, children receive a hot, nutritious meal. This is made up of locally produced foods like rice, dried African locust bean seeds, African carp and sesame leaves, and of fortified food rations supplied by the World Food Programme. The rations include 150g of fortified corn-soy blend, 3g of iodised salt and 10g of palm oil per child per day.

There is also a second feeding category: girls in selected schools in Ghana’s three northern regions are given food to take home each time they attend school for 85% of the month. This food includes rice, maize, vegetable oil and iodised salt.

The ration programme for girls started in 1999 and has been gradually absorbed into the bigger school feeding programme. It has yielded remarkable results: girls’ enrolment in these selected schools has grown from 9,000 to 42,000 between 1999 and 2016. Retention rates have doubled to 99%. This scheme is essential in tackling gender disparity in education, particularly in northern Ghana’s food-insecure and deprived communities where girls’ education is not often prioritised by families.

Sadly the ration programme for girls is being slowly phased out – its managers believe their work is done given the huge spike in retention rates. Now the focus will be entirely on the bigger school feeding scheme, which has also been very successful. It has, according to my own research:

- increased school enrolment by 20%.

- reduced truancy and absenteeism.

- lowered school drop-out rates.

- improved individual academic performance and the participating schools’ overall performance.

These are all excellent, positive results. But there’s still work to be done.

Plotting the next steps

One of the biggest problems facing the programme is a lack of funding. It cannot be rolled out more widely because there just isn’t enough money.

Schools that aren’t currently part of the programme are struggling. A survey conducted in Ghana’s Sekyere Kumawu district found that non-beneficiary schools were actually losing pupils. The same study revealed that pupils were switching to the schools that offer the scheme in order to receive the benefits.

The government and stakeholders need to put mechanisms in place that will strengthen the existing programme, allow it to expand into other schools and make it sustainable. The government must wean the programme of its reliance on donor funds. It can learn here from the experiences of South Africa’s national school feeding programme, which is funded by the country’s National Treasury. This approach ensures that the government takes ownership of the programme and plans for its sustainability.

Policy will be important: the programme falls under Ghana’s National Social Protection Strategy, but should be bolstered with a strong legal and policy framework that clearly maps the way forward. This legislation should delineate the guidelines for implementation and institutional mechanisms to make sure the programme delivers what is necessary.

Finally, a robust monitoring and evaluation framework will be needed to ensure that the programme’s organisers learn from their failures and successes. This way adjustments can be made along the way so that Ghana’s children can keep getting the meals they need at school.

NB This version of the article, with permission from the author, does not include the hyperlinks to supporting articles found in the original. Click the title for the full version of the text, published under a CC BY ND licence in The Conversation, which should be used for reference and sharing.

Download the answers here: Unit 13 reading answers

Pronunciation /i:/ and /ɪ/

Hearing the difference between long and short vowel sounds, and being able to say them clearly, is one of the core pronunciation features which aid mutual understanding when a non-native speaker of English talks to another non-native speaker.

Focus on /i:/ and /i/

Long vowel sound /i:/ e.g. equal, hungry

- The most common spelling is ‘ee’ or ‘ea’ (green, each) but there are others: receive, be, even, security.

Short vowel sound /i/ e.g. promise, nutrition

- The most common spelling is ‘i’ (listen, quick, politics, promise), but there are others: women, busy.

Function – Talking about setting up and running a programme

In Unit 9 you learned the word ‘robust’ to describe a business enterprise. Can you give a definition for that term? Do this quiz to see how many terms associated with setting up and running a programme that you read in the text (Ghana’s school feeding programme is slowly changing lives) you can remember. Click the ‘start’ button, then for each of the 9 sentences click the option (A or B) that is a synonym for the part of the sentence in bold that relates to setting up and running a programme.

Practice

Listening – The racial hunger gap in American cities and what to do about it (5 mins)

![]()

Credit: The Conversation Weekly podcast. Associate Breaking News Editor and Co-Host, and Gemma Ware, Editor and Co-Host. Licence: CC BY ND

Before you listen

- You’ll hear a leading expert on food insecurity, Prof Gunderson, talk about food insecurity in the US. Can you remember the definition of food insecurity from the infographic at the beginning of this Unit?

- In America food insecurity is much higher for black people and American Indians than it is for white people. What do you think might be some of the reasons for this?

- Look at the word cloud created from the transcript. The most frequently used words (the biggest ones in the cloud) are: food (29), insecurity (18), rates (10), areas (7), Americans (7), cities (6). With the title in mind (‘The racial hunger gap in American cities) create a sentence that uses as many of these words as possible and predicts the main point of the listening.

Listen

Play the audio here

(Or access The Conversation podcast and listen from 4.39mins to 9.47mins).

Download the answers here: Unit 13 listening

Download the transcript here: Unit 13 listening transcript

Vocabulary – Consequences of hunger

In Unit 7 you learned that growing up in poverty weakens later health. Read the two extracts below that talk about this – one from the text (Ghana’s school feeding scheme) and one from the listening (The racial hunger gap in American cities). Use the context to help you work out the meaning of any of the words/phrases in bold that you have not come across before.

‘Without proper food, children are prone to stunted growth or are underweight for their age. And their schooling suffers, too: research has repeatedly shown that children struggle to learn when they are not properly fed and nourished’.

‘Improving food security is a no-brainer. People who don’t get the food they need have more problems with depression and other mental health issues. Seniors have lower nutrient intakes, and children have higher rates of anaemia. Young children with severe malnutrition usually have poor mental development’.

Practice

There is plenty of research that demonstrates this link between hunger and adverse physical health and mental health in school-age children. Other adverse effects include:

- Mental health issues: depression, stress, anxiety, behaviour problems.

- Physical health issues: stunted growth, underweight or obesity, anaemia, tiredness or hyperactivity, chronic illnesses such as diabetes, asthma, eczema, and epilepsy.

- Mental development: impaired learning, poor emotional regulation, and decreased productivity.

Create a profile of a girl whose well-being has been impacted by the Ghana School Feeding Scheme.

- Create details such as name, age, family situation, details about her school, friendships, etc.

- Describe the level of food insecurity she and her family suffer and use some of the above terms to describe how this has impacted her well-being (mental health, physical health, mental development).

- Describe the positive impact that the scheme has had on her and her family.

If you are learning in a classroom, present your profile to another pair of students when you have finished, using some of the terms you have learned.

Writing

In this Unit you’ve learned about food insecurity and seen how effective a school feeding scheme can be. Rosibel Quintero and Isabel Sánchez, two indigenous women in Panama, have also tackled the issue of hunger among school children and their story illustrates the considerable impact local community schemes can have.

Read Rosibel and Isabel’s story and write a response to it that incorporates what you know about health and well-being and SDG2 Zero Hunger. Write about:

- The problem of hunger in this local context.

- How United Women of Bonyic tackled the crisis.

- The long-term benefits of the project.

- Any other topic relevant to the challenges of hunger and SDG2.

Challenges and Leadership: Naso Tjër Di Women Reinvent Themselves to Face the COVID-19 Crisis

In the Bocas del Toro Province of Panama, two indigenous women, Rosibel Quintero and Isabel Sánchez, founded the United Woman of Bonyic (OMUB) to develop and manage community gardens. Seeing some children faint during class because they were not physically suited for the long-distance travel to school, Rosibel Quintero and Isabel Sánchez believed that the OMUB could be a solution to malnutrition among children and created a small vegetable garden at the school.

“At the time, we did not have universal scholarship or opportunity network subsidies for families, not milk and nutritional foods that kids have at school today provided by the authorities. Still, we didn’t want to see more children weak at the school”, said Rosibel Quintero, President of OMUB.

After 17 years of effort, their dream of a garden had grown into a small natural lodge for tourists with a vegetable garden containing cucumber, cacao, lettuce, plantain, tomatoes, cilantro, yam and other traditional crops. It also generated income to support the pursuit of university studies.

Due to disruptions to the tourist industry during the pandemic which left the women without income and resources, the community resumed community vegetable gardens, adding new crops with financial support of a small donations program from the United Nations Development Programme. They were able feed their children during the pandemic from the community gardens and saved enough to buy cell phone cards for children to continue their schools virtually.

Department of Economic & Social Affairs Statistics Division (2022) ‘Bringing Data to Life: SDG impact stories from across the globe.’ Available at: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2022/SDG2022_Flipbook_final.pdf

Speaking

Read the summary and answer the questions below:

SDG2 Summary

Nature provides direct sources of food and a series of ecosystem services (e.g. pollination, soil formation, nutrient cycling, and water regulation) supporting agricultural activities and contributing to food security and nutrition.

Increasing world population and changes in consumption patterns put pressure on the environment creating the need to produce food for an additional two billion people by 2030, while preserving and enhancing the natural resource base upon which the well-being of present and future generations depends. This is important considering that unsustainable expansion of agriculture has created serious environmental problems such as soil erosion, water pollution through agrochemicals, and emission of greenhouse gases.

Climate change and `natural` disasters such as droughts, landslides and floods greatly affect food security. Disaster risk management, climate change adaptation and mitigation are key to increase harvests quality and quantity.

Reproduced with kind permission of the UN Environment Programme. Copyright (2023). All rights reserved.

- At this moment, which countries are affected by famine?

- Can you identify any links between climate change and food security in those regions, or in your own local context?

- Are there any solutions to food insecurity, and the way it negatively affects the well-being of people in both developed and developing countries?

- What is your opinion of the fact that food insecurity is much higher for some racial groups than others?

- Can you give a definition for the words in bold above?

A reminder that if you have access to the internet and are studying by yourself without other people to practice your spoken English with, you can use artificial intelligence (AI) to gain fluency practice. See here for instructions and prompts.

Here are some prompts related to this Unit:

- ‘Let’s have a dialogue about food insecurity. Let’s talk about [insert name of country] and people going hungry there. Tell me your ideas and give me lots of opportunities to respond.’

- ‘Let’s have a dialogue about the racial hunger gap in America. How can you explain the gap? Tell me your ideas and give me lots of opportunities to respond.’

- ‘Let’s have a dialogue about how hunger or poor nutrition can affect a child’s development. Tell me your ideas and give me lots of opportunities to respond.’

Looking Ahead to Unit 14

In Unit 14 you’ll be looking at the issue of food waste.

- Do you live in a context where edible food gets thrown away?

- Is food insecurity an issue for you or your community?

- Do you know of any initiatives designed to reduce food waste in your local context?

Use the menu bar on the left hand side of the screen to access Unit 14.