4 Developing an Active Learning curriculum aimed at improving engagement and retention in foundation year students on an extended degree

Nicky Milner

Introduction

To address poor engagement and retention in the foundation year of the extended medical sciences degree programme at Anglia Ruskin University (ARU), the curriculum has been redesigned to embed an active learning approach, Team-Based Learning (TBL), to provide formative feedback.

The work presented in this chapter forms part of an ongoing action research study, exploring the phenomenon of student engagement of students registered on a foundation year course which is shared with three separate awards. Starting in Semester 1 of the 2016/17 academic year, five successive interventions have been introduced at the start of each semester. Student feedback, collected from module evaluation surveys (MES) and course performance reviews have informed each subsequent intervention.

Themes emerging from MES collected prior to the first intervention identified a number of issues contributing to poor engagement and retention of students, such as a lack of formative assessment, and the need for personalised tutorial support. One intervention included the creation of a clearly structured online learning environment, which embeds regular team-based formative assessments that are aligned to the summative assessment. This enabled individual performance data to be obtained following completion of short individual tasks. A later intervention built on this through the creation of a Personalised Learning Log, which is completed by students and identifies areas where performance falls below the pass mark. The most recent intervention, introduced in Semester 2 of the 2018/19 academic year, is focussing on developing a strong sense of belonging through interdisciplinary learning and development of ownership of learning through student-led focus groups.

This chapter explores the pedagogy behind this curriculum redevelopment and considers the impact of mapping course and module learning outcomes to ensure that learning and teaching material is constructively aligned and that assessment has relevance.

Student feedback received from MES and student-focused committees, often identify concerns with factors include clarity and relevance of teaching material, teaching methods, and the layout and timely availability of course content on the university’s Learning Management System, Canvas.

In addition, student feedback from module evaluation surveys highlighted the lack of clear preparation for the summative assessments as an area that they wanted to be improved. This issue is particularly challenging in a course where students are registered on one of three different medical science courses.

The Foundation Year

For this chapter, the term ‘foundation year’ is used to describe a generic preparatory year in a four-year, extended degree programme, shared by three awards offered by the Faculty of Health, Education, Medicine and Social Care (HEMS): BSc (Hons) Medical Science, BSc (Hons) Pharmaceutical Science, and BSc (Hons) Applied Nutritional Science.

The foundation year, importantly, is not a Foundation Degree, which the QAA (2015) define as a combination of academic and vocational learning and require either ‘top up’ or entry to the remaining elements of the course to graduate with an honours degree. Nor is the foundation year a separate course to the three-year degree as, following successful completion of the foundation year, students seamlessly progress onto one of the three-year courses.

Students on the foundation year are often accepted with lower grades (i.e. 48 UCAS Tariff points – one A Level or equivalent) than the standard intake (i.e. 96 UCAS Tariff points). This results in the common problem of maintaining motivation in students with a range of different levels of academic ability. Personal support is needed to provide regular detailed, and often repetitive, academic support to weaker students, while stronger students frequently work at a quicker rate and get bored quickly.

Aims

The overall aim was to create a sustainable, inclusive learning environment with space for students to practice in preparation for their summative assessments, where learning activities are clearly aligned with the intended learning outcomes of each module and the course.

The purpose of the redesigned curriculum was also to create space in the timetabled sessions for consolidation of knowledge and exploration of topics being taught through additional practice and personalised academic support through greater interaction with students on a one to one basis.

A further aim of the curriculum redesign is to provide a learning environment which is flexible and accommodates students from across the spectrum of academic ability.

Thematic analysis of MES free-text comments collected after introducing more regular team-based formative activities, indicated that student experience was enhanced as a result of introducing more interactive activities where one to one academic support was provided. Examples of positive comments relating to increased motivation and use of a variety of formats for learning, such as online quizzes, crosswords and debates. Students requested more activities for practice when asked to identify areas for improvement. Overall, student feedback suggested that they were responding positively to the interventions.

In addition, the foundation year has a low retention rate caused by students withdrawing early due to poor academic performance. It was anticipated that the implementation of an active learning style curriculum would also address this issue.

According to student attendance data and anecdotal evidence from delivering sessions, attendance in class is poor in the foundation year. Gaining an insight into how students engage with their learning journey, particularly outside the classroom, will help influence the design of an effective curriculum to help students maximise their academic performance through enhanced engagement and support.

Literature review

Student engagement has been widely covered in the literature (Kuh, 2001; Mann, 2001; Healey, Flint and Harrington, 2014). Thomas (2012), in particular, reports on some interventions which promote the need to develop a sense of belonging through inclusive and participative engagement. Successful interventions which achieved this, such as active learning which provides prompt feedback, interactions between students and staff and collaborative activities, help improve retention and success in the early stages of a course. This highlights the importance of the design of the course to help students become more engaged learners so they are effective and successful beyond their studies into employment.

Many students do not always understand the value of attending class and often prefer to be selective about when they attend campus to study. Newman-Ford et al. (2008) listed some reasons for absenteeism including ‘assessment pressures, poor lecturing, inconvenient timing of the lecture … poor quality of [the] lecture … low motivation, stress … work overload … [and] work commitments’ (p.700). Kuh, Gonyea and Palmer (2001) also list increased travel costs to university, a reduction in the number of students living on campus, the need to support families and cope with living costs, as contributory factors to non-attendance.

Another factor which has an impact on retention is the students’ sense of belonging, as this has been shown to improve student motivation, engagement and promote active collaboration which all help foster creativity through sharing knowledge and ideas within peer groups. Building a sense of belonging and partnership through the creation of an active community with clear identity are therefore important factors in improving student engagement (Thomas, 2012).

Both the academic curriculum and the wider environment within the academic institution must provide an environment designed to support an effective learning journey for students, and reinforce the need to continue learning outside the classroom. To successfully engage with their course, students must also be motivated, able to attend university, and actively participate in their studies (Fredricks, Blumenfeld and Paris, 2004).

These students may still engage with their studies, however, through learning from lecture material at home, albeit with limited, or no, interaction with academic staff or peers. However, much of the valuable learning occurs during participation in class activities where new knowledge can be created and academic staff can ensure that students adequately understand key topics. Non-attending students also lose the opportunity to develop graduate attributes and employability skills such as networking, digital literacy, team working, and oral communication skills.

Poor engagement can result in early withdrawal, and student retention is a critical issue in Higher Education (HE). The Higher Education Academy (2015) Framework for student access, retention, attainment and progression in higher education clearly states that ‘Students cannot learn or progress unless they are engaged’ (2015: 1), highlighting engagement as a phenomenon which underpins student success.

Students who engage with an effective active learning environment have an additional opportunity to engage in meaningful dialogue with academic staff and their peers, which helps encourage engagement with a learning task and promotes regular attendance through an enhanced experience (Zhao and Kuh, 2004).

Active learning is a pedagogically sound teaching approach and is now used widely across various subjects in the HE sector. Research has shown that active learning can improve engagement and academic performance (Prince, 2004; Gibbs, 2018). Here, timetabled classroom sessions offer lecturers an opportunity to enhance their style of teaching so that the time is used to clarify knowledge, provide feedback and create meaningful discussion.

As Prince (2004) explains:

Active learning is generally defined as any instructional method that engages students in the learning process. In short, active learning requires students to do meaningful learning activities and think about what they are doing (2004: 223)

Modern active learning pedagogies have been developed around student-led participative learning, rather than the over reliance on more passive methods such as ‘sage on the stage’ lectures with minimal student involvement in learning activities.

One active learning method which has been shown to improve academic performance and engagement is TBL (Michaelson, 2001; Koles et al., 2010). TBL was designed to address these issues specifically and utilises the positive aspects of peer-assessment and accountability (Michaelson and Sweet, 2008). TBL has been shown to be effective across a range of subjects including microbial physiology (McInerney and Fink, 2003), pharmacology (Zgheib, Simaan and Sabra, 2010) and engineering (Najdanovic, 2017).

A key element in TBL is team activities which poses a challenge for academic staff since student feedback traditionally reflects a negative approach to group work (Moraes, Michaelidou and Canning, 2016) particularly when linked directly to summative assessment (Willcoxson, 2006; Chapman et al., 2010; Cilliers, Schuwirth and Adendorff, 2010; Crossaud, 2012). Nevertheless, TBL has been shown to improve student satisfaction with learning in groups (Clark et al., 2008).

One of the challenges of TBL is the time required to produce relevant active learning material for each session. Creating meaningful, constructively aligned, active learning exercises is time consuming, but this has been shown to enhance engagement and academic performance. Failure to do so can result in reduced student engagement, which negatively impacts student attendance, confidence and motivation (Enfield, 2013; Arnold-Garza, 2014; Tolks et al., 2016).

Flipped learning is an approach which requires students at arrive at class having completed a pre-session activity. During the class, students engage with interactive problem-based activities within their group (e.g. TBL team). To work effectively, students must prepare for the session beforehand (Michaelsen, Knight and Fink, 2004).

TBL is designed to follow a set process where students complete a short individual Readiness Assurance Test (iRAT), where scores are collected. This is immediately followed with a team Readiness Assurance Test (tRAT), which generates debate, discussion and competitive environment, which demonstrably showcases the students’ learning behaviour and understanding of key topics related to the module.

To provide students with a supportive and engaging environment conducive to success, assessment needs to be constructively aligned to the module and course learning outcomes (Biggs, 2003). This constructivist approach to learning underpins active learning strategies. When the learning activities are designed using this approach, students have been shown to engage more deeply with their studies (Biggs, 2003).

A constructivist approach was, therefore, selected for the curriculum design to create a learning environment, which allowed space for students to obtain formative feedback, engage with one-to-one discussion with an academic tutor, and to identify the relevance of the teaching to the assessment. The need to emphasise learning as a journey was considered when designing the underlying curriculum structure. The result of this was to embed pre-session and post-session activities into the curriculum.

Methodology

An action research approach was selected for this study. Student feedback was obtained through routine course evaluation data, on a semester basis. This feedback was used to help inform the next development. A natural, cyclic process was in place because of the structure of the academic year (semester-based course) and related feedback mechanisms. Curriculum focus groups are in the process of being implemented. The aims of these groups will be used to create space for staff and students to discuss their experiences with the foundation year curriculum, which will support the design and development of each academic year in their four year course.

Course content is delivered face-to-face, on a semester-based model, with a total of six modules, which are two 30-credit modules (one per semester) and four 15-credit modules (two per semester). Consequently, there are six MES responses for each academic year. In addition, student representatives present a report at Student-Staff Liaison Committee (SSLC) meetings (held each semester), on what they want to keep, change, and stop or start doing on the course. These data are used to inform curriculum enhancement for the next delivery.

SSLC data is qualitative, and staff engage with the student representatives and other academic and support staff, at the meetings. MES data provides mixed data, with module satisfaction measured using Likert scales and free-text comments. The free-text section enables students to provide feedback, allowing them to expand on their quantitative responses. When combined with analytical data from the Student Engagement Dashboard, this information was used to inform the development of an effective curriculum which supports improvements in engagement and retention through developing student ownership of the course, which leads to academic success, and progression towards the final award.

Student feedback from these key points in the academic year, provided qualitative data, which was used to inform each intervention (see Table 4.1).

Intervention 1

In response to student feedback from MES in Semester 1 of 2016/17, Intervention 1 focused on improvements to the structure of the course material on the Virtual Learning Environment (VLE). This involved the introduction of short pre- and post-session learning activities for each timetabled session, such as videos and articles relating to the topic being covered. Weekly sessions for each module were clearly identified on the VLE and the topics related to the summative assessment criteria. In class, students worked in teams on shared problem-based activities and practice questions for assessments.

|

Academic Year |

Semester |

Intervention |

Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2016/17 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

2 |

1 |

Introduction of short pre- and post-session learning activities |

|

2017/18 |

1 |

2 |

Introduction of Topic Block Model |

|

|

2 |

3 |

Introduction of discussion groups and writing workshops |

|

2018/19 |

1 |

4 |

Introduction of Personalised Learning Log |

|

|

2 |

5 |

Introduction of interdisciplinary learning, and student-led focus groups |

Qualitative data derived from the 2016/17, Semester 2 (Intervention 1) MES was largely positive, with students commenting that “group work was interesting and challenging”, and the space being created through regular team-based activities meant that the “pace of [the] course fits all learning styles and is engaging for people that are both struggling and people that are advanced”. However, students wanted more “one to one tutorials”, “more practice” and “more group work”.

Intervention 2

This feedback led to the creation of the Topic Block Model (Intervention 2) (Semester 1, 2017/18). Regular short Canvas quizzes were introduced to test knowledge of, and engagement with, pre-session learning activities. It was clear from active participation in class that many students were engaging with the preparatory material. More one-to-one discussions were provided through fortnightly team-based formative assessment tasks (Week 2 of each repeating unit in the Topic Block Model).

The Topic Block Model – A novel active learning curriculum

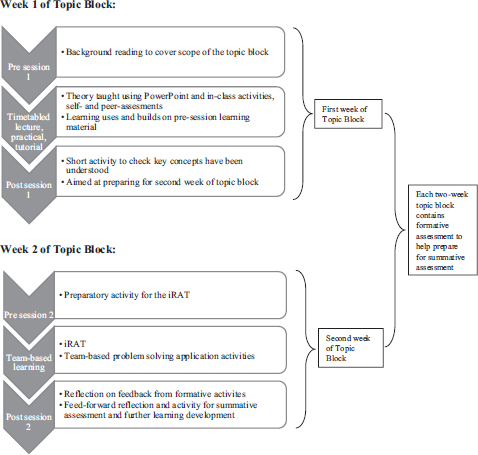

The first stage of the project was to redesign the foundation year curriculum of the extended medical sciences degree programme. The new design includes adapted elements of TBL to help address poor engagement and retention. A novel course structure, the Topic Block Model, was created to provide flexible delivery content using active learning methods. Six topics are identified in each module which form the focus for learning activities over a two-week period called a Topic Block (see Figure 4.1). The advantages of this design are that it helps with consolidation and extension of knowledge and understanding through the creation of space. The interactive sessions within the Topic Blocks allow for peer instruction to occur. Course content is reinforced through active learning methods, particularly in Week 2 of the Topic Block.

The timetabled sessions are varied according to the module and usually have a mixture of lecture and practical sessions supported by workshops, seminars and tutorials. Each timetabled session is reinforced using a short post-session learning activity, such as an online quiz to check understanding of concepts relating to the topic covered in the session. The motivation for designing this format was to improve student engagement by highlighting the learning journey as being a continuous thread of activities in which all students should immerse themselves to maximise their chances of success.

Feedback from the MES indicates that students are engaging with their assessments early, which is also shown by an improvement in assignment submission rates. It was noted that in the 2017/18 and 2018/19 academic years, first time submission rates for assessments in all foundation year modules was higher than the previous year (>95 per cent, n=18; and >90 per cent, n=16 respectively), suggesting that students were engaging with their assessments earlier and obtaining feedback through engagement with regular formative activities. This phenomenon will be explored in more depth at a later stage.

Figure 4.1 The Topic Block Model

Student feedback indicated that while the amount of one-to-one tutorial support was good, several students wanted to “go into more depth when talking about topics” and wanted to explore more topics.

Intervention 3

To create a space in which to stretch students, so they could explore a greater range of topics and maintain motivation, extra-curricular activities were implemented as part of Intervention 3 (Semester 2, 2017/18). These included discussion groups and writing workshops, where students could expand their knowledge and gain more one-to-one support with academic writing and understanding of course topics.

Semester 2 MES data demonstrated that students who engaged with these activities found them beneficial, with comments including “excellent and well structured”, and “Great tutorial support for the essay writing workshop”.

Intervention 4

The second focus of the project involved identifying those students at risk of failing module assessments or being withdrawn from their course due to academic failure. Students and academic staff have access to the university’s Student Engagement Dashboard which collates engagement data in three key areas: access to Canvas; ‘tap-in’ data for attendance in class, and; use of the University Library. These data help academic staff and students gain a perspective on how an individual student is engaging with various aspects of their studies. Whilst these metrics are useful general indicators of engagement, they do not provide data on personal academic performance during the teaching period (and before summative assessments are completed). This data, when combined with the general engagement data, offers a greater opportunity to intervene positively, with students who are at risk of failing module assessments or being withdrawn from their course due to academic failure.

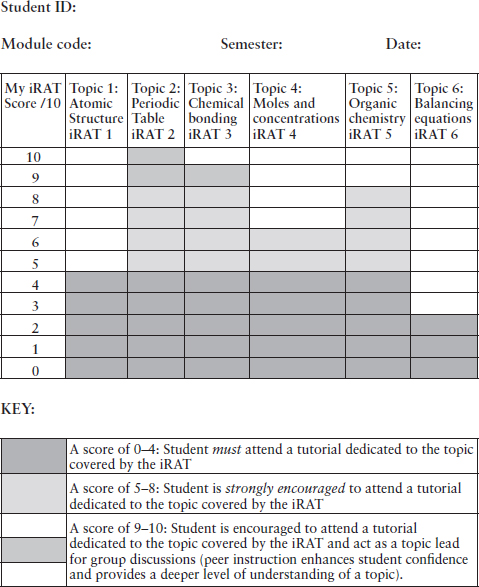

Intervention 4 (Semester 1 2018/19), therefore, concentrated on implementing tools which helped students take greater ownership of their learning and academic progress. Using regular in-class formative tests for each topic provided a structure for recording the performance of an individual in a system which enabled students to easily identify whether they needed to seek additional academic support in real-time. The Personalised Learning Logs were created and students were encouraged to make use of them.

The aim of the logs is to provide bespoke support in ‘real-time’ through self-assessment of personal academic performance, and to alert staff to the possibility of academic failure.

Students record their iRAT scores from Week 2 of the Topic Block in their log. Figure 4.2 shows an example Learning Log for a student who has achieved a satisfactory level of understanding of Topics 2 and 3, is encouraged to request some help with Topics 4 and 5, and must seek assistance with Topics 1 and 6.

Figure 4.2 Example Personalised Learning Log

The Personal Learning Logs highlighted those students who needed individual (personalised) tutorial support to address topics where they have performed below expectation.

Take up of the logs was challenging when student attendance was poor and as a result, we are working with students through curriculum focus groups to identify how we can utilise them in future personal tutorial sessions.

Intervention 5

Intervention 5 (Semester 2, 2018/19) built on Intervention 4 and explored ways that students want to use the Personalised Learning Logs. In addition to academic performance, confidence was also measured through the iRAT and tRAT process. This was designed to improve engagement with learning through building greater awareness of retention of knowledge through deeper learning practice.

With in-class activities constructively aligned to the module assessment, teaching staff had the opportunity to provide regular formative feedback through dialogue with the students in the classroom. This created the opportunity for feedback to be provided, in the session, in the form of whole-class (e.g. mini-clarification lecture), team-based (e.g. discussion around an activity) and individual feedback (e.g. directed reading to support an area of additional academic support).

Working in teams reinforced the requirement for students to be accountable for their learning, and encouraged them to improve their engagement outside the classroom (i.e. engaging with pre-session learning and peer-led activities). Student feedback from MESs administered following Interventions 2 and 3 reflected an improvement in student motivation and evidence for a greater level of independent study. MES comments included, “I found this module to be challenging which is what I felt I needed to engage my mind and also to push me to find what my limits are” and “concentrate on one topic at a time,” and “helps me understand more”. Evidence suggested that students were feeling motivated to research outside the classroom more, with comments such as, “I enjoyed this module as it was very research based. I enjoyed finding out about different diseases”.

To strengthen engagement generally, monthly student-led interdisciplinary discussion groups and writing workshops were introduced. The discussion groups enabled students to explore the wider curriculum through topical discussions, and to meet other students from public health, medical and science courses from across the faculty.

These sessions also support students to build self-confidence through active participation in discussions and debates. The writing workshops provide an opportunity for students to access additional assessment support through engagement with their assessments early in the semester. The sessions are facilitated by a course tutor and students work independently on an activity of their choice, for example, a draft summative assignment or a formative activity, such as writing an abstract. Student attendance and engagement in the discussion groups has increased with time and consequently these have been continued and now form part of the structure of the curriculum through the introduction of a site on Canvas. There are currently 44 participants registered on the new site, which has increased from an average of six students in 2017/18.

Conclusion

This study explores the phenomenon of learning behaviour in students registered on a shared foundation year in three extended medical sciences degrees. Student retention, attainment, and attendance in foundation years across ARU have been highlighted as areas where improvement is needed. To address these issues, an active learning curriculum was developed through successive interventions, introduced on a semester basis.

Student feedback from module evaluation data helped inform each intervention. Throughout the study, student feedback demonstrated improvements in their engagement had been made to the curriculum. These included a Topic Block Model which enabled regular formative team-based assessments to be used to support academic performance. A more personal, timely system of identifying at risk students has been introduced through the design of Personalised Learning Logs.

Next steps and planning

The interventions introduced in this study have drawn on aspects of TBL, such as iRAT and tRAT, collaboration with a shared problem, and generation of active discussion, and following evaluation, aims to formally introduce TBL modules into the curriculum in the 2019/20 academic year. The next step of this study is to set up curriculum focus groups, where students will work in partnership with course leaders, to evaluate the effectiveness of the teaching methods and the value of using Personalised Learning Logs as a tool for monitoring student engagement and success. This will result in the creation of a toolkit to provide guidance for academic staff who wish to design active learning curricula to improve engagement and retention in other courses.

References

Arnold-Garza, S. (2014) ‘The flipped classroom teaching model and its use for information’, Communications in Information Literacy, 8 (1), 7–22.

Biggs, J. (2003) Aligning Teaching and Assessment to Curriculum Objectives, (Imaginative Curriculum Project, LTSN Generic Centre).

Chapman, K.J., Meuter, M.L., Toy, D., and Wright, L.K. (2010) ‘Are Student Groups Dysfunctional? Perspectives from Both Sides of the Classroom’, Journal of Marketing Education, 32 (1), 39–50.

Cilliers, F.J., Schuwirth, L.W., Adendorff, H.J. Herman N. and van der Vleuten, C.P. (2010) ‘The mechanism of impact of summative assessment on medical students’ learning’, Advances in Health Science Education, 15: 695. Online. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-010-9232-9 (accessed 25 March 2019).

Crossuard, B. (2012) ‘Absent Presences: The Recognition of Social Class and Gender Dimensions Within Peer Assessment Interactions’, British Educational Research Journal, 38 (5), 731–49.

Enfield, J. (2013) ‘Looking at the impact of the flipped classroom model of instruction on undergraduate multimedia students in CSUN’. TechTrend, 57 (6), 14–27.

Fredricks, J.A., Blumenfeld, P.C. and Paris, A.H. (2004) ‘School Engagement: Potential of the Concept’, State of the Evidence Review of Educational Research, 74 (1), 59–109.

Healey, M., Flint, A. and Harrington, K. (2014) Engagement through Partnership: students as partners in learning and teaching in higher education. The Higher Education Academy.

Kuh, G.D. (2009) ‘The National Survey of Student Engagement: Conceptual and Empirical Foundations’, New Directions for Institutional Research, Spring 2009, 141, 5–20.

Kuh, G.D., Gonyea, R.M. and Palmer, M. (2001) The Disengaged Commuter Student: Fact or Fiction? National Survey of Student Engagement, Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research and Planning. Online. http://www.nsse.indiana.edu/pdf/commuter.pdf (accessed 30 March 2019).

Mann, S.J. (2001) ‘Alternative Perspectives on the Student Experience: Alienation and Engagement’, Studies in Higher Education, 26 (1), 7–19.

McInerney, M.J. and Fink, D. (2003) ‘Team-Based Learning Enhances Long-Term Retention and Critical Thinking in an Undergraduate Microbial Physiology Course’. Microbiology Education, 4, 3–12.

Michaelsen, L.K., Knight, A.B. and Fink, L.D. (Eds) (2004) Team-Based Learning: A Transformative Use of Small Groups in College Teaching. Sterling: VA-Stylus.

Moraes, C., Michaelidou, N. and Canning, L. (2016) ‘Students’ attitudes toward a group coursework protocol and peer assessment system’. Industry and Higher Education, 30 (2), 117–28.

Najdanovic, V. (2017) ‘Team-based learning for first year engineering students’. Education for Chemical Engineers, 18, 26–34.

Newman-Ford, L., Fitzgibbon, K., Lloyd, S. and Thomas, S. (2008) ‘A large scale investigation into the relationship between attendance and attainment: a study using an innovative, electronic attendance monitoring system’. Studies in Higher Education, 33 (6), 699–717.

Prince, M. (2004) ‘Does Active Learning Work? A Review of the Research’. The Research Journal for Engineering Education, 93 (3), 223–31.

Thomas, L. (2012) Building Student Engagement and Belonging in Higher Education at a Time of Change: A summary of findings and recommendations from the What Works? Student Retention and Success Programme. HEFCE, Higher Education Academy, and Action on Access.

Tolks, D., Schäfer, C., Raupach, T., Kruse, L., Sarikas, A., Gerhardt-Szép, S., Kllauer, G., Lemos, M., Fischer, M.R., Eichner, B., Sostmann, K. and Hege, I. (2016) ‘An introduction to the inverted/flipped classroom model in education and advanced training in medicine and in the healthcare professions’. GMS Journal for Medical Education, 33 (3), 1–23.

Willcoxson, L.E. (2006) ‘It’s Not Fair! Assessing the Dynamics and Resourcing of Teamwork’, Journal of Management Education, 30 (6), 798–808.

Zgheib, N.K, Simaan, J.A. and Sabra, R. (2010) ‘Using team-based learning to teach pharmacology to second year medical students improves student performance’. Medical Teacher, 32 (2), 130–35.

Zhao C.M. and Kuh, G.D. (2004) ‘Learning Communities and Student Engagement’. Research in Higher Education, 5 (2), 115–38.