3 What’s wrong with traditional teaching? A case for transitioning to active and collaborative learning

Simon Twedell

Introduction

The University of Bradford has offered an undergraduate pharmacy programme for many years. The programme became modular in 1992, with each module situated within one of four disciplines, taught wholly by academics from these disciplines. The programme was delivered by an equal combination of large lectures and small-group classes. Subject content was delivered by lectures and applied in workshops, which were replicated for delivery to six cohorts. However, there was variable attendance in lectures (typically 50 per cent), and little preparation for the applied workshop activities, which were often used to redeliver content. Part of the problem was the way lectures were delivered; students were predominately passively listening and sometimes taking notes. If the subject content was not engaging or perceived as relevant or interesting, then some students were more likely to engage in side conversations with peers. Arguably, university policy to provide lecture notes to students in advance compounded the problem. Furthermore, the size of the cohort was an issue, it is easy to be anonymous in a crowd of 150–200 students. The final problem was the way in which content was used, with subject knowledge often taught in isolation, for example without effective alignment with programme outcomes. Subject content was chosen by individual academics, often without providing the context. In effect we were not motivating students to fully engage in their studies.

Learners are often motivated by personal connection to tasks (Oyler et al., 2016). When learning activities are embedded in meaningful contexts, personalised, or when learners are offered a choice of aspects of their learning contexts, then this increases learner motivation, engagement and the depth of learning (Cordova and Lepper, 1996). The programme team decided to optimise engagement through curriculum design, motivating students to study by using subject content that inspired them, captivated their interest, and ensuring they understood how this learning was important to both their programme and future careers.

What is engagement?

Fredricks et al. (2004), identify three dimensions of student engagement, albeit in school children:

- Behavioural engagement: students comply with behavioural norms, attend classes, follow the rules, and are not disruptive. Students contribute towards class discussions and participate in learning and academic activities.

- Emotional engagement: discernible affective reactions such as demonstrating interest, happiness, enjoyment, or a sense of belonging.

- Cognitive engagement: students are invested in their learning, go the extra mile, and seek out and enjoy challenges.

Trowler (2010) suggests engagement is a continuum, with positive behaviours that are productive or constructive at one end, and negative behaviours that can be disruptive, obstructive or counter-productive at the other. Trowler argues that between these poles could be a range or gulf of ‘non-engagement’ such as withdrawal or apathy (see Table 3.1).

Positive engagement with educationally purposeful activities, whether in-class or self-directed out-of-class, has been shown to lead to learning (Coates, 2005). Attendance research shows a negative correlation between the numbers of hours of missed classes and student performance, with low performers significantly more likely to believe classes did not benefit them, suggesting disengaged students (Hidayat et al., 2012).

Trowler’s (2010) continuum for individual learner engagement commences with ‘student attention’, where they are focused on the teacher or the task in hand. This moves to ‘student interest in learning’, students are now curious and connected with the subject. ‘Student involvement in learning’ is next; here students choose to become actively involved, perhaps through note-taking, or through peer discussion, suggesting a degree of ownership of their learning. The penultimate point is ‘student active participation in learning’ which could manifest as asking or answering questions, seeking further information or clarification, or constructing links with previous learning. Finally, ‘student-centredness’ may involve students in the design, delivery, and assessment of their learning, for example co-creating learning resources or assessment criteria. It may also involve giving students a choice of what or how to learn, for example providing electives or choice of assessments. Trowler is not advocating that all programmes should aim to be completely student-centred, only that this approach might be beneficial in engaging or empowering some students in parts of the curriculum.

|

|

Positive engagement |

Non-engagement |

Negative engagement |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Behavioural |

Attends classes and participates with enthusiasm |

Skips classes with no good reason or excuses |

Boycotts or actively disrupts classes |

|

Emotional |

Interest |

Boredom |

Rejection |

|

Cognitive |

Meets or exceeds assignment requirements |

Assignments late, rushed or absent |

Redefines parameters for assignments |

Rather than using large lectures and multiple repeated workshops, we sought a learning and teaching strategy that created order by engaging students in active learning in the classroom. The strategy needed to retain the benefits of small-group teaching, but be scaled for a large cohort of students, hence removing the need for multiple repetitive classes. This change would require a shift in our thinking as academics, from delivering ‘teacher-centred content’, to facilitating ‘student centred-learning’. Weimer (2002) sums up our belief at that time that learning was an ‘inevitable outcome of good teaching, and so we focused on developing our teaching skills’ (2002: xi). Staff development had tended to focus on skills for delivery rather than approaches to learning.

For the existing learning and teaching strategy to be effective, students had to assimilate knowledge from lectures before it was applied in workshops. However, students did not always have the time or motivation for this, and many of our lectures at the time were passive and content-heavy. Historically, we dealt with negative behaviours by trying to make lectures more engaging, for example by using audio-visual aids and technology. Others have used techniques such as ‘Peer Instruction’ to encourage and make use of peer-to-peer interactions during lectures. In this technique questions are embedded into lecture presentations for students to answer, increasing participation, dialogue and active involvement. Peer instruction has resulted in positive outcomes (Crouch and Mazur, 2001; Fagen et al., 2002; Lasryet al., 2008). However, it still requires students to attend class, be motivated to study content prior to the class, and actively engage in discussions with peers in the session. Gauci et al. (2009) found that active participation increased students’ motivation and engagement and that those who answered questions posed in class achieved better results than those who chose not to. In the learner-centred classroom, the role of the teacher shifts significantly from the knowledge expert who talks from the front of the classroom to one who enables and encourages students to explore, discuss and engage with subject content through well-designed exercises and assignments. However, it may be empowering for the teacher to encourage discussion and debate, or disempowering as they may feel they have less control, status or autonomy.

Blouin et al. (2008) call for a renaissance in education, arguing that didactic approaches are not effective because students are not held sufficiently accountable for their pre-class learning. They contend that because students do not read, study or learn the foundational facts sufficiently out-of-class, then too much class time is dedicated to content delivery rather than application. Whilst didactic approaches can be an efficient method of knowledge transfer, arguably they do not teach students to critically assess information to solve problems. Students may know a plethora of facts but Blouin et al. (2008) assert that graduates are ill equipped with the skills to use these facts to solve ‘practice-based problems’. In a follow-up paper, Blouin et al. (2009) make three recommendations for reform: rejecting the majority use of class time for factual transmission of information; challenging students to think critically, communicating effectively and developing skills in problem-solving; and designing curricula based on sound, evidence-based educational principles, (cf. Chickering and Gamson, 1999; Bransford and Ebrary, 2000).

van der Vleuten and Driessen (2014) argue that educational practice and educational research are misaligned and current practice relies heavily on content transmission. They suggest that curriculum designers should consider adopting evidence-based learning strategies that include elaboration, cooperative learning, feedback, mentoring and the flipped classroom.

We conducted a small study in 2011 to explore the experiences of educators and students using more traditional forms of teaching to inform the development of a new curriculum. The following describes the research question, methods, findings and conclusions from this study.

Methods

Research Question

What are educator and student experiences of using traditional methods of learning and teaching?

We chose to use qualitative research methods using a phenomenological approach to the design of the study to capture the lived experiences of academics and students as they engaged in traditional teaching methods. Following ethical approval, academic staff who had been delivering the Bradford MPharm programme for at least two years were invited to take part in a semi-structured interview. Semi-structured interviews allow for a set of questions to be asked of all participants with the researcher free to ask supplementary follow-up questions to probe deeper, clarify meaning, or to pursue an interesting or relevant line of enquiry (Robson, 2011). Sixteen of the 18 eligible members of staff participated. Following a piloted interview guide, the researcher explored academics’ experiences of traditional teaching to try to understand their successes and frustrations in engaging students in learning activities.

For the student view, nine fourth-year students took part in a focus group to explore their experiences of lectures and small group classes. The interviews and focus groups took place in a private room, lasted approximately 30 minutes, and were audio recorded to capture the words and paralanguage used.

The recordings were transcribed by the researcher and analysed inductively, with NVivo, using Thematic Analysis (Creswell, 2009). The themes were then interpreted and represented in the context of published work and presented with reflexive insight, as the researcher was an experienced academic, external to the programme but familiar with it.

Findings

The Staff View

The themes that emerged from the area of enquiry were student engagement and student learning.

Student engagement

When asked about their experiences of teaching most participants spoke of their struggles in engaging students in large classes, particularly lectures. The issues ranged from poor attendance and passivity through to noise and active disruption in lectures.

Issues worsened when lectures were used predominantly for content delivery. Cohort size and disruption were linked: as cohort size reduced, so did disruption. The question remains whether pedagogy or group size is the most important variable. Lectures used to be optional, and attendance during this time was often less than half, suggesting a high degree of disengagement. Students who did attend were positively engaged and there was little disruption. Those that choose not to attend presumably studied independently. It was only when lectures were made compulsory and attendance monitored that disruption increased.

Lectures are an efficient means of transferring knowledge to large groups and can stimulate interest, explain concepts, and direct learning. However, lectures are not particularly effective at teaching skills, changing attitudes, or encouraging higher order thinking. Large lectures encourage passivity with little opportunity to process and critically appraise new knowledge (Cantillon, 2003). Perceived relevance of content was also deemed an important factor in engaging students. Students needed to see the value in engaging with course concepts and understand the context of why they are learning particular subjects and its relevance to their future careers.

Some participants focused on classroom control to maintain order (Gibbs and Jenkins, 1992), this is what Biggs (1999) calls the first stage of teacher growth which focuses on ‘what the student is’ with blame of a poor lecture experience often placed on the students. My own early experiences were similar. I found that if the lecture was pure content delivery of a subject that was not particularly interesting, or to which students were unable to directly relate, they soon became bored and sometimes disruptive. Most participants did discuss strategies to increase engagement in lectures, usually by including some kind of activity.

Teachers who introduce interactivity into classes are moving into ‘Stage Two’ of teacher growth focusing on ‘what the teacher does’ with a clear focus on improving the process of teaching delivery, by embedding a video clip into a lecture, for example.

Audio-visual technology has been proposed to increase interactivity and enliven lectures. However, Fink (2004) argues that this strategy fails to address two major problems associated with large lectures: anonymity and passivity. Nonetheless, students may not always be actively thinking in a lecture, but they might learn the content after the lecture on their own, or revisit it in a future tutorial, or when preparing an essay or written assessment. When questioned about large group lectures most of the participants believed that they had limitations in terms of learning.

While most of the participants were not in favour of lectures there was no unanimous consensus. Two participants did enjoy lecturing on their subject:

I enjoy lecturing because I’ve been doing it for 25 years and I used to have 150 and that number wasn’t a problem for me (Participant 1)

Well I enjoy talking to the students, being the person who leads the lecture rather than having to facilitate (Participant 13)

The performance role of the teacher, holding an audience by telling them how much you know about your subject, can be very enjoyable for the teacher. Penson (2012), for example, argues that the ability to captivate the audience using humour and animations and breaking up the monologue with activities to reduce passivity can be an enjoyable experience for students and teachers.

My own journey as an academic took me through all three phases referred to by Biggs (1999). I initially designed my modules so that they were predominantly delivered by lectures and practicals. Essentially, lectures covered content and practicals focused on application and problem-solving. However, I found lectures turgid and passive for learners so I introduced activities and problems into lectures to engage them and show context. I later moved the entire content into student study guides that included reading, web-resources and activities that eventually replaced lectures allowing more time to apply knowledge in practical classes. Although I was unaware of the terminology at the time, I had effectively ‘flipped’ the learning. My problem at this time was motivating students to engage in pre-class study.

As programme leader, I presided over a programme with growing student numbers. The learning and teaching strategy for a programme of 70–80 students per year was less effective with 200 students. Lectures to 200 students became problematic as staff struggled to maintain order and create an effective learning environment. Small group workshops and practical classes became larger and required numerous repetitions, putting a strain on staff, rooms and timetables. It was time to stop trying to ‘impose order’ in the classroom and try and ‘create order’ with a new strategy.

Most participants expressed a preference for small group teaching arguing that attendance and engagement was greater, however small cohorts required multiple repetitions.

Two participants pointed out that lectures should have been for content delivery and workshops and practical classes for application. However, as students were not attending lectures, then workshops were increasingly being used for content delivery, which was ineffective and inefficient.

I’d always preferred the smaller group teaching to lectures. I always preferred to facilitate rather than just talking at them. However, students would come into tutorials still expecting to be taught, they expected you to deliver content to them rather than coming prepared with questions. And we had to repeat this six times (Participant 9)

One participant reported more success with taking a flipped approach to teaching.

What I did like were workshops where they had the topics in advance, they did a bit of work on the topics and we then had some sort of dialogue in the workshop. That seemed to engage them quite well and most of them were motivated to take part (Participant 6)

However, another participant commented that they forced the students to prepare in advance by checking their work and asking those that had not prepared for the classroom to leave. This is really another example of attempts to enforce order rather than create it.

Student Learning

The second theme focused around student learning and how effective traditional methods were: is it students’ responsibility to engage with the lecture content, or is it academia’s responsibility to create the optimal conditions for learning to occur? Perhaps creating the right conditions will help students better engage with course content and lead to improved learning.

The majority of staff participants did not perceive that students gained sufficient understanding of the content from lectures in order to apply this effectively in subsequent small group classes, although there were contrasting views:

I don’t think they learned anything in a lecture, they never came prepared, even if you asked them to they’d never do it, well maybe a few keen ones would. The majority wouldn’t have a clue what was in the last lecture. You can tell that when you ask questions from the week before. I wouldn’t assume that they are reading anything after the lectures either (Participant 13)

I think learning definitely takes place in a lecture. I covered some knowledge-based topics that were hard for them to follow and put in a lot of time and research to focus on the difficult point they would not understand … My lecture notes were fully comprehensive and understandable to people who didn’t attend my lectures … Lectures do the job and are definitely the most efficient way of doing it (Participant 14)

Two teachers did manage to engage their students in lectures and created comprehensive notes for them to read afterwards, possibly to try to compensate for poor lecture attendance, although arguably this could contribute to poor attendance. One teacher, however, saw it as their role to provide opportunities for students to learn in lectures and that is where their responsibility ended. Students were then free to choose to attend or not. Their argument was that it was not their role to provide multiple opportunities for students to learn based on their individual learning preferences. The following participant sums up one of the problems with this approach:

Looking at the exam answers, I think a lot of students took notes in lectures but didn’t do much with them until the time of the exam so learning did look as if it was a bit superficial (Participant 8)

In my experience, lectures can be used to provide context to explain the relevance and importance of concepts and content to future learning and future roles beyond graduation and correct any misunderstandings or answer questions. However, they should involve activities and peer discussion, be interactive, engaging, interesting and include dialogue and discussion between students and between students and teachers. My most successful and engaging lectures in a traditional curriculum came at the end of the module. Here students were not given any new content, instead they applied their learning from the module to solve authentic problems in pairs, and this was followed by discussion of the answers or solutions provided.

The Student View

The fourth-year students had experienced numerous lectures and were able to reflect on their experiences. From a student perspective the experiences of lectures were mixed. Some benefited from them, others did not. The general consensus was that they wanted a blended approach with some lectures, particularly where there were difficult concepts, and perhaps some podcasts to refer back to. Some students did identify that lectures did not motivate them to study the material again until close to the exams, however others were sufficiently motivated to pick up a book afterwards.

In response to staff and student feedback, we introduced a new learning and teaching strategy for the MPharm programme that focused on active and collaborative learning, and was scalable to reduce the need for multiple, repetitive small group workshops.

The innovation

In 2012 we introduced a new MPharm programme delivered predominantly by Team-Based Learning (TBL), a structured approach to the flipped classroom with an incentivisation framework to optimise individual pre-class preparation and in-class engagement, discussion and decision-making.

Sibley et al. (2014) described TBL as:

a special form of collaborative learning using a special sequence of individual work, group work and immediate feedback to create a motivational framework in which students increasingly hold each other accountable for coming to class prepared and contributing to discussion (2014: 6)

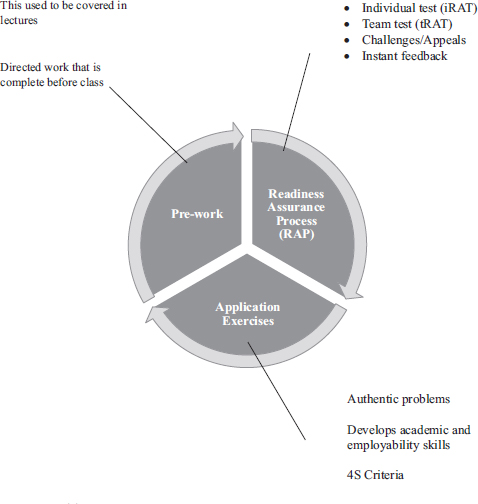

TBL shifts the focus of classroom time from conveying course concepts by the teacher to the application of course concepts by student learning teams (Michaelsen et al., 2002). TBL is made up of a number of phases.

Team Formation

At the start of the semester, teachers allocate students to permanent teams of five to seven students, with diverse resources, who work together for the entire semester or year. Bruffee (1993) suggests an optimal group size for collaborative decision-making is five or six. Teams may lack the intellectual resources with fewer than five and more than seven may results in sub-teams forming and a reduction in functional coherence.

Social cohesion supports learning because group members bond together through regular interaction, and consequently want both team and individuals to succeed. Furthermore, Slavin (1996) argues that learner interactions increase achievement through cognitive processing:

Students will learn from one another because in their discussions of the content, cognitive conflicts will arise, inadequate reasoning will be exposed, disequilibration will occur, and higher quality understandings will emerge (1996: 49)

Cognitive psychology suggests that for knowledge to be retained and related to previous learning, it needs to be restructured or elaborated (Wittrock, 1986). Similarly Fosnot (1996) describes learning as requiring ‘invention and self-organisation on the part of the learner’ (1996: 29). Slavin (1996) goes on to suggest that ‘one of the most effective means of elaboration is explaining the material to someone else’ (1996: 50).

Preparation Phase

Students prepare for class by individually studying course content in advance. This may include learning resources and activities created by the teacher, or signposting students to other sources such as textbooks, podcasts, video clips, and web resources. Most often it is a combination of both original and curated content. Preparatory work should be contextualised to show the relevance of the learning to the degree and to future roles beyond graduation.

Readiness Assurance Phase

Engaging with the preparatory work is incentivised by the Readiness Assurance Process (RAP). Students initially take a short, graded but low stakes individual Readiness Assurance Test (iRAT) on their learning from the Preparation Phase. This is immediately followed by an identical team-Readiness Assurance Test (tRAT) whereby students repeat the test again as a team and receive immediate feedback. Teams are actively engaged in discussion during the tRAT, often learning from each other and sometimes competing with other teams. Results are available to teachers to facilitate an informed discussion on any key concepts with which students may have struggled. Teams can also challenge a question or answer, and are encouraged to do so, with the aim of revisiting content and further developing their critical thinking skills.

The purpose of the RAP is that assessment drives learning. Assessment shouldn’t only be used to measure student learning at the end of a course or module but should be used during it to support the learning process. Assessment-as-learning (Schmitz, 1994) includes six essential criteria which form part of the TBL RAP. Maddux (2000) suggests that using assessment-as-learning as an on-going iterative process can be of benefit when using the following six criteria. These are:

- The inclusion of clear learning outcomes

- Allowing multiple performances

- Having explicit criteria

- Use of expert judgment

- Providing productive feedback

- Use of self/peer assessment

Application Phase

Teams are now ready to apply their new knowledge to solve authentic and challenging problems. Problems should be authentic and relevant to the learner, with fellow learners and teachers providing guidance to scaffold learning (Davies, 2000). Applications are designed to create discussion and make a team decision, which they publically defend. Teams are asked to justify and elaborate on their answers in a teacher-facilitated debate. Application exercises follow the ’4S’ design criteria (Sibley et al., 2014). Learners work on ‘significant’ and authentic challenging problems relevant to their discipline; all teams work on the ‘same’ problem so go through the same learning experiences, which makes later class discussion richer. Teams are forced to make a ‘specific choice’ or collaborative decision, which they later justify by presenting their argument and rationale. Finally all teams ‘simultaneously’ reveal their decision at the same time to publicly commit to their decision; this further motivates task engagement and prevents answer drift. Learners engage in regular team and class discussions, to enable deeper understanding of course content.

Since the implementation of TBL in 2012, we have evaluated our deliveries which provided us with conclusive evidence that TBL as active learning approach addresses the challenges we encountered in the previous lecture-focused deliveries of the MPharm programme (cf. Nation, Tweddell & Rutter, 2016; Nelson & Tweddell, 2017; Tweddell, Clark, D. and Nelson, 2016; Active Collaborative Learning, 2019).

Figure 3.1TBL Unit Diagram

Conclusion

This research has shown that most of the educators in the study had experienced Trowler’s (2010) characteristics of non-engagement and negative engagement when lecturing to large numbers of students. This seemed to be more problematic when lectures were used to deliver one-way content and was exacerbated by growing student numbers, and the introduction of compulsory attendance. Some educators experienced some success in enhancing positive engagement in lectures through the use of interactive tasks and technology. However, lectures were mostly being used to provide content to be applied in subsequent small group workshops. For this to work effectively, learners must revisit the content between the lecture and the workshop and this was not happening, so workshops were being used for content delivery. Students did see the benefit of having some lectures, particularly when the concepts were difficult to grasp. A small minority claimed to be motivated to study after a lecture, although most were not.

As a result of the findings, a blended approach was proposed; this could include some non-compulsory lectures for those that benefited from them which, if recorded, could be accessed on demand. Some focused lectures do probably still have a place in undergraduate education as they are a useful tool to set the context for the subject content, revisit previously learned concepts that may be important to new learning, and provide an opportunity for students to hear from a subject expert. The lecture experience for students and staff is improved when the student numbers are smaller and when there is some form of interactivity between student and teacher and between students, and therefore involving some form of active learning. Arguably, lectures should not be compulsory and if students wish to watch a recorded lecture at a time of their convenience, or independently self-study the content, then this may develop their skills as independent learners. However the learning that takes place in lectures is not always optimal and data from the focus groups suggests most students are not sufficiently intrinsically motivated to self-study or prepare for subsequent classes designed for application, higher-level thinking and problem solving.

As a result of these findings, TBL was introduced as the main learning and teaching strategy. Staff reported better attendance, attainment, engagement and interaction in classes with mostly positive feedback from staff and students about their experiences.

References

Active Collaborative Learning (2019) Addressing barriers to student success. Scaling Up Active Collaborative Learning for student success. Final Report 28 October 2019. Nottingham Trent University: OfS project site. Online. https://aclproject.org.uk/draft-scaling-up-active-collaborative-learning-for-student-success-report/ (accessed 15 January 2020).

Biggs, J. (1999) ‘What the Student Does: teaching for enhanced learning’, Higher Education Research & Development, 18, 57–75.

Blouin, R.A., Joyner, P.U. and Pollack, G.M. (2008) ‘Preparing for a Renaissance in pharmacy education: the need, opportunity, and capacity for change’, American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 72 (2), 42.

Blouin, R.A., Riffee, W.H., Robinson, E.T., Beck, D.E., Green, C., Joyner, P. U., Persky, A.M. and Pollack, G.M. (2009) ‘Roles of innovation in education delivery’, American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 154.

Bransford, J. and Ebrary, I. (2000) How People Learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Bruffee, K.A. (1993) Collaborative learning: Higher education, interdependence, and the authority of knowledge. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Cantillon, P. (2003) ‘Teaching large groups’, BMJ, 326 (7386), 437.

Chickering, A.W. and Gamson, Z.F. (1999) ‘Development and adaptations of the seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education’, New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 1999 (80), 75–81.

Coates, H. (2005) ‘The value of student engagement for higher education quality assurance’, Quality in Higher Education, 11 (1), 25–36.

Cordova, D.I. and Lepper, M.R. (1996) ‘Intrinsic motivation and the process of learning: Beneficial effects of contextualization, personalization, and choice’, Journal of Educational Psychology, 88 (4), 715–30.

Creswell, J.W. (2009) Research Design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA; London: Sage.

Crouch, C.H. and Mazur, E. (2001) ‘Peer instruction: Ten years of experience and results’, American Journal of Physics, 69 (9), 970–77.

Davies, P. (2000) ‘Approaches to evidence-based teaching’, Medical Teacher, 22 (1), 14–21.

Fagen, A.P., Crouch, C.H. and Mazur, E. (2002) ‘Peer instruction: Results from a range of classrooms’, The Physics Teacher, 40 (4), 206–09.

Fink, L.D. (2004) ‘Beyond small groups: Harnessing the extraordinary power of learning teams’, Team-Based Learning: A Transformative Use of Small Groups in College Teaching, 3–26.

Flipped Learning Network (2014) ‘What Is Flipped Learning ? The Four Pillars of F-L-I-P’, Flipped Learning Network. Online. https://flippedlearning.org/definition-of-flipped-learning/ (accessed 24 June 2014).

Fosnot, C.T. (1996) ‘Constructivism: Theory, perspectives, and practice’, Constructivism: A psychological theory of learning. New York: Teachers College Press, 8–33.

Fredricks, J.A., Blumenfeld, P.C. and Paris, A.H. (2004) ‘School Engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence’, Review of Educational Research, 74 (1), 59–109.

Gauci, S.A., Dantas, A.M., Williams, D.A. and Kemm, R.E. (2009) ‘Promoting student-centered active learning in lectures with a personal response system’, Advances in Physiology Education, 33 (1), 60–71.

Gibbs, G. and Jenkins, A. (1992) Teaching Large Classes in Higher Education: how to maintain quality with reduced resources. London: Kogan Page.

Hidayat, L., Vansal, S., Kim, E., Sullivan, M. and Salbu, R. (2012) Pharmacy student absenteeism and academic performance, American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 76 (1), 8.

Khanova, J., Roth, M.T., Rodgers, J.E. and Mclaughlin, J.E. (2015) ‘Student experiences across multiple flipped courses in a single curriculum’, Medical Education, 49 (10), 1038–48.

Lasry, N., Mazur, E. and Watkins, J. (2008) ‘Peer instruction: From Harvard to the two-year college’, American Journal of Physics, 76 (11), 1066–69.

Luscombe, C. and Montgomery, J. (2016) ‘Exploring medical student learning in the large group teaching environment: examining current practice to inform curricular development’, BMC Medical Education, 16 (1), 184.

Maddux, M.S. (2000) ‘Institutionalizing Assessment-As-Learning within an Ability-Based Program’, Journal of Pharmacy Teaching, 7 (3–4), 141–60.

McLaughlin, J.E., Griffin, L.M., Esserman, D.A., Davidson, C.A., Glatt, D.M., Roth, M.T., Gharkholonarehe, N. and Mumper, R.J. (2013) ‘Pharmacy student engagement, performance, and perception in a flipped satellite classroom’, American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 77 (9).

Michaelsen, L.K., Knight, A.B. and Fink, L.D. (2002) Team-Based Learning : A Transformative Use of Small Groups. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Moffett, J., Berezowski, J., Spencer, D. and Lanning, S. (2014) ‘An investigation into the factors that encourage learner participation in a large group medical classroom’, Advances in Medical Education and Practice. Abingdon: Psychology Press.

Nation, L., Tweddell S. and Rutter, P. (2016) ‘The applicability of a validated team-based learning student assessment instrument to assess United Kingdom pharmacy students’ attitude toward team-based learning’. Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professions, 13 (2016), 1–5.

Nelson, M. and Tweddell, S. (2017) ‘Leading Academic Change: Experiences of Academic Staff Implementing Team-Based Learning’. Student Engagement in Higher Education Journal, 1 (2), 100–116.

Oyler, D.R., Romanelli, F., Piascik, P. and Cain, J. (2016) ‘Practical Insights for the Pharmacist Educator on Student Engagement’, American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. Alexandria, 1.

Penson, P.E. (2012) ‘Lecturing: a lost art’, Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning. Elsevier, 4 (1), 72–6.

Robson, C. (2011) Real World Research: A Resource for Users of Social Research Methods in Applied Settings. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Sander, P., Stevenson, K., King, M. and Coates, D. (2000) ‘University Students’ Expectations of Teaching’, Studies in Higher Education, 25 (3), 309–23.

Schmitz, J. (Ed.), (1994) Student Assessment-as-Learning at Alverno College. Milwaukee, WI: Alverno College Institute.

Sibley, J., Ostafichuk, P., Roberson, B., Franchini, B. and Kubitz, K. (2014) Getting Started With Team-Based Learning. Sterling, Virginia: Stylus Publishing.

Slavin, R.E. (1996) ‘Research on Cooperative Learning and Achievement : What We Know, What We Need to Know’, Contemporary Educational Psychology, 21, 43–69.

Trowler, V. (2010) Student Engagement Literature Review, Higher Education Academy.

Tsang, A. and Harris, D.M. (2016) ‘Faculty and second-year medical student perceptions of active learning in an integrated curriculum’, Advances in Physiology Education. Bethesda, 446–53.

Tweddell, S., Clark, D. and Nelson, M. (2016) ‘Team-based learning in pharmacy: The faculty experience’. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning. 8 (1), 7–17.

van der Vleuten, C.P.M. and Driessen, E.W. (2014) ‘What would happen to education if we take education evidence seriously?’, Perspectives On Medical Education, 3, 222–32. Online. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24925627 (accessed 10 April 2019).

Weimer, M. (2002) Learner-centered Teaching: Five key changes to practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Wittrock, M.C. (1986) Handbook of Research on Teaching: A project of the American Educational Research Association. New York, NY: Macmillan; Collier-Macmillan.

Wong, T.H., Ip, E.J., Lopes, I. and Rajagopalan, V. (2014) ‘Pharmacy students’ performance and perceptions in a flipped teaching pilot on cardiac arrhythmias’, American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 78 (10).