12 Using place to develop a culture for active pedagogy

Andrew Middleton

Introduction

This chapter reflects on the complexity of developing a culture of active pedagogy across an institution. It describes some of the initiatives led by the author in his central educational development role with responsibility for academic practice and learning innovation in a UK post ’92 university. It focuses on developments undertaken in the context of the institution’s strategic drive to develop ‘future learning space’ under the sponsorship of the Deputy Vice Chancellor.

The chapter uses an autoethnographic approach. Following the setting of context and an explanation of the methodology, five accounts of educational change and academic innovation are presented as vignettes; short stories about the future learning spaces work from the author’s perspective. The stories cover a two-year period which challenged diverse stakeholders to not only co-operate but work imaginatively, while embracing appropriate risk-taking to transform practices.

An analysis of the overarching story through this chapter has elicited three themes which form the concluding discussion. The first theme reflects on the conundrum of situated innovation as space or place. The second considers the tension between strategy and opportunity in developing active learning. Finally, co-production as an appropriate basis for active development for active learning in complex situations is considered.

Methodology

This study takes an autoethnographic approach. James (2015) argues for autoethnography as a methodology that elucidates practice and makes ‘explicit the deliberations, choices and motives that drive our actions and ‘theories in use’’ (p. 102). Autoethnography uses reportage from the reporter’s own personal and emotional life (Bloor and Wood, 2006). It is a form of self-narrative that places the reporter as the protagonist (Atkinson and Reed-Danahay, 1999). The methodology allows for critical reflection on rich and complex experience through introspection and dissolves ‘the boundary between the author and objects of representation’ (Butz and Besio, 2009: 1660).

Vignettes provide reportage in a short storytelling format and offer a useful qualitative approach for representing complex experience. Their use is realistic and provides a way to represent ‘fuzzy experience’; situations that cannot be clearly defined because their significance or meaning is dynamic, often being about change over time, with such episodes involving multiple people with multiple roles and drivers. Fuzzy experiences typify educational development which, due to their non-dualist nature, are typically inconvenient for researchers, though nevertheless highly significant to understanding activity and space.

While the stories reflect on work involving many people, a rationale for autoethnography is that ‘the writer is freed from the ethical dilemmas implicit in the attempt to represent any experience’ (Bloor and Wood, 2006: 18). However, no person’s experience can claim to be completely divest of the experiences and interests of others. Before I set out the vignettes, which feature many people as co-protagonists, I declare that, overall, this chapter is a story of good will, shared endeavour and co-operation and I acknowledge the professionalism of my colleagues. An overriding challenge for all of us was not whether, but how to work co-operatively and, as Vignette 1 reveals, we started from a position of disconnection. The other vignettes record how we moved towards a shared desire to connect and integrate our work which we understood to be a pre-condition for implementing an institution-wide shift from pragmatic pedagogic didacticism towards an ethos of active learning.

The voice of the chapter now changes as the story of developing a future-ready space for learning is recounted through the vignettes.

The story

Vignette 1: Silos and surprises

The email invited people to hear about the progress being made on plans for fitting out a new building for one of our faculties on our campus. As the institutional lead for academic practice and learning innovation, I was surprised I had not been alerted earlier about the construction of a new teaching facility. I wondered, “Who was representing the teaching and learning imperative in this development?”

I attended the meeting later that week with about seven others: the Estates Manager, two librarians, the University’s Head of AV and his colleague from IT Networks, a faculty-based project manager, and the University Head of Catering. They were discussing the detail of the social space; where the printers would be located and how this was already really determined by commitments made to the installation of conduits discussed many months ago. I wondered whether I should be there: decisions had been made, the technical language was impenetrable, and nobody was talking directly about teaching or learning even though every comment seemed to reinforce a naïve and shallow set of assumptions about what academics do and how learning happens.

I realised the pink boxes circumscribing an indecipherable central space on the plans for each floor were classrooms. The assumption, which was later confirmed for me, was that the lecturers would know what to do because the classrooms were standard classrooms. It was apparent that the plans had been signed off a while ago.

“Which academics have been involved in the design so far? How were the specifications drawn up?” I asked.

“We’ve tried to involve academics but they never turn up, and they can’t give us the answers we need.” Colleagues needed answers to technical questions. Academics either did not have a view, were not empowered to answer on behalf of others, or had no understanding of what the questions meant or why they might be important. Colleagues read this as an essential disinterest in the project, beyond the questions concerning their own office accommodation, with the exception of two specific space requirements to support Early Years Education and Science Education.

Despite this inauspicious introduction to what appeared to be an ill-conceived ‘new build’ project, the people I met that day were to become some of my closest colleagues for the next few years. My respect for their openness, courage and professionalism grew steadily. I soon learnt about their frustrations with academic disinterest and their appreciation of the opportunity a new build creates as a catalyst for innovation. I learnt how building developments do not pause for academics to learn about teaching innovation or for the moments in the academic year when they can give such questions the time they deserve.

As I left, I promised I would engage and represent the academic voice, one way or another.

Vignette 2: Creating a typology as a common opportunity

Initially I noticed that discussion about learning spaces at institutional level was demarcated by a culture of jargon, policies, and budgets which created a counter-productive ‘silo mentality’ that suppressed innovation.

As I began to talk in subsequent meetings of the Learning Spaces Operations group about the implications of their decisions for innovative pedagogy and the learner experience, a common desire to break through their deficit discourse blossomed. I had felt excluded by their jargon and I realised that a common project to develop a learning spaces typology would benefit everyone. More to the point, the institution needed a way to talk about its various classrooms and ensure that Timetabling, Facilities Management, AV refurbishment cycles, and IT Services had a way to interoperate. Works were not co-ordinated and clearly aspects of the teaching estate had suffered over the years by fits and spurts of investment in one area or the other. Classrooms were functionally and aesthetically incoherent due to the variety of new and worn out furniture, decoration schemes, and AV updates; works apparently carried out without logic. I realised that academics could not depend on a consistent offer. All concerned were open about their different approaches to managing refurbishment but felt they were determined by circumstances imposed on them. I realised that once a new build had been launched, it steadily decays in different ways at different rates. From a teaching and learning point of view, spaces were functional, but the estate spoke loudly of a lack of attention to academic and student belonging and this reflected poorly and unfairly on the institution’s attitude to learner engagement.

The task of creating the Learning Spaces Typology was challenging. Categorising room types proved nearly impossible. We agreed it would be meaningless to define too many types and we eventually agreed baseline descriptions for lecture theatres, small classrooms, large classrooms, PC labs, and specialist facilities including science laboratories and studios. The classrooms were sub-divided according to capacity. Capacity is a contentious matter because it is dependent on room configuration and student-to-floor-space ratio (Boys, 2011).

While developing the Typology, we introduced SCALE-UP, an active learning pedagogy in which students engage in problem-solving through structured group work framed in a specific classroom environment (Beichner, 2008). As other vignettes describe, we began to devise active learning facilities by developing our appreciation, and that of others, of whiteboards, floor space and technological components. However, we were trying to create a typological system while our understanding of its dimensions were still developing.

We never did get to the point of surveying every room against the Typology as we had intended. Our senior sponsor left before we got to that point, but we achieved a deeper understanding of what matters in designing, maintaining and supporting the teaching estate: an understanding of space and its relationship to learning along with a common language and stories about spaces for learning.

Vignette 3: Learning space walks in the twilight zone

Conversation, experience and space intersect around the act of walking. Walking creates a familiar, common space for forming trustful and confident relationships that can inform understanding.

Haigh (2015) considers the value of conversation as a context for professional learning. He had recognised how his most valuable professional development came from the just-in-time impromptu conversations he had with his colleagues. He analysed such conversations and identified serendipity, improvisation, parity, timeliness, contextuality, the use of storytelling, openness and trust as valuable features of conversational encounters. These values are also evident in third place theory (i.e. social surroundings other than Home (First Place) and Work (Second Place)) (Oldenburg, 1989), characterised by its neutrality and good conversation. While change projects often focus on processes, deep and lasting change is cultural and, with this in mind, I devised Learning Space Walks.

I have organised many learning walks designed to consider spaces for active and student-centred learning. The walks, taking two hours, run during the twilight zone between four and six o’clock, fittingly straddling the boundary marking the end of the normal working day and, by implication, normal working roles. The idea of twilight zone is both practical and symbolic, presenting the possibility of a deviant space in which more relaxed attitudes can create the right mood for walking together; it is a tacit boundary space shaped by a collective generosity to hang on at work for an extra hour in the day. The group, therefore, comes to embody a collective curiosity.

The Learning Space Walks use a co-created route. Walkers are each invited to nominate and make the case for a ‘viewpoint’ when they register to take part. As organiser, I select about five viewpoints and devise a useful route and discussion outline.

I have organised walks explicitly for academics and for senior managers, but they are most effective with a mix of participants: a student walking with a Vice Chancellor or a member of the Estates team walking with a couple of academics. Questions or ideas are posed at each viewpoint and then the walkers set off again engrossed in discussion for the next 10 or 15 minutes. Few instructions are given. People know how to go for a walk!

I have observed how people normally walk and talk in groups of two or three. Clusters tend to overhear parallel conversations, and this leads to merging or exchanging behaviours. I look out for quiet people and my job, as host facilitator, is to bring them into conversational groups.

The viewpoints act as stimuli. We might visit a classroom suggested by one person who might say, “I wanted to bring us here to tell you about the day when I was teaching here and …” The conversations will pick up on the stimulus and by the time we reach the next viewpoint people may have wandered ‘off topic’ but into areas of mutual interest.

Finally, we will gather in a campus café or classroom to share and reflect on our meanderings. People are vested in hearing about what others discussed and how this was different to their own conversations.

Walking is a versatile active learning space. It has structure, but as an active space the structure is usefully loose. I have used walks to consider a variety of foci; not only learning spaces. I also have extended the approach by creating global ‘twalks’ in which co-created routes run in parallel across time-zones using social media to connect walking groups (Middleton and Spiers, 2019).

Vignette 4: Stand-up pedagogy and white-boarding

A few things came into focus at about the same time for me. I took a colleague, a professor well-known for his work on experiential learning, on a Learning Space Walk. Unusually, it was just the two of us. We had walked as members of a group a week or so earlier and this led to us wanting to take a closer look at one or two things. He showed me a classroom with no windows; a left-over space from some development. Nevertheless, it was regularly timetabled. “How did this happen?!”

We continued on our way and observed the ‘classroom litter’ in every room: that is, the inevitable broken chair, the disused Over Head Projectors, tables with wonky legs, and odd contrivances that had once had a purpose, though no longer. Every room was like this. We observed the plentiful whiteboards, many of which were not cleaned. We observed tables and chairs stacked perilously high. “Surely a hazard” we noted as we realised that this structure demonstrated how some tenacious academic had determinedly rearranged the room to suit their pedagogy despite the challenges.

At about the same time, I was emailed a photograph from a Maths lecturer who was visiting a South African university. The picture showed a line of mobile whiteboards arranged down the centre of a hall. Students were touring and interacting with the whiteboard wall. Another colleague in Maths explained how they got their students to work side-by-side at whiteboards on mathematical problems. I was working on the Typology and had begun to realise that wall and floor spaces, not just room capacity and technological infrastructure, were significant to active learning space.

The outcome of this was an initiative called Stand-Up Pedagogy (SUP). I explained my thoughts to my collaborators in professional services. Later the Estates and AV Managers surprised me by finding an unused teaching room. We took it off the timetabling system and I arranged for all the furniture and IT to be removed so that the space was bare, save for whiteboards, pens and erasers. It looked bizarre, but it implicitly communicated a pedagogic challenge. The overwhelming sense was of there being nowhere to hide. It signalled loudly that if you’re in the room you were expected to interact with the people and the whiteboards. I called for volunteer innovators from the academic community.

The project emerged as an unexpected opportunity and meant that I did not have time to properly plan and support it. There were technical obstacles too: the room could not be formally timetabled in case people were assigned to it unwittingly, yet the students in the SUP pilot had to be notionally assigned to another room to ensure something appeared in their schedule. This confused them. Further, we could find no adequate way of managing whiteboard pens and erasers. Standing for a full session could be tiring and we realised we needed to allow for students with disabilities by reintroducing three chairs. While it was not a perfect experiment, it was a useful start. We learnt a lot about the value of wall space in any classroom which led me to devising many active learning wall-based methods including collaborative drawing, concept mapping, myriad Post-It Note exercises, and gallery techniques. In turn, this led me to consider how floor space can be used to set out ‘crime scene’ scenarios, flip chart activities, photographs, and other objects for student interrogation.

Vignette 5: Flexible classrooms

As in SCALE-UP (see Chapter 1), the efficacy of flexibility comes from adjusting only specific pertinent variables. Fixed tables, for example, can create a strong foundation upon which interactivity can thrive. This principle applies to both teaching and the space it uses. SCHOMS, AUDE and UCISA (2016) highlight how flexibility introduces weakness to the physical design of space: wheels can fail on chairs, hinges on tables, and so on. Adaptation, rather than flexibility, is a more useful way of considering active spaces and active pedagogies.

To test this, I argued for the development of a series of three rooms in the heart of our university to act as both a lab for the investigation of active learning and as a ‘showcase’ suite of adjacent classrooms. Each room had its own definite ‘built pedagogy’ (Monahan, 2002). I wanted to raise the visibility and debate around active learning.

Building on the sound relationships developed with AV colleagues, and having no budget beyond that available in their annual refurbishment programme, we established three different active learning classrooms (see Figures 12.1, 12.2 and 12.3), each nominally accommodating 36 students. We specified each room according to a different idea about active learning:

Lined with whiteboards, and without a dominant lectern, these ideas were mostly achieved through table configuration. I produced pedagogic guidance to encourage staff to adopt a range of active pedagogies and ran CPD workshops in each of the rooms to model white-boarding activities like listing, sorting, ordering and concept mapping in response to problem stimuli. Mostly, however, the sessions afforded an opportunity to ponder on ideas and take a few risks together; to discover that learning objectives can be met by involving participant learners as collaborators and even co-conspirators in an active learning experiment.

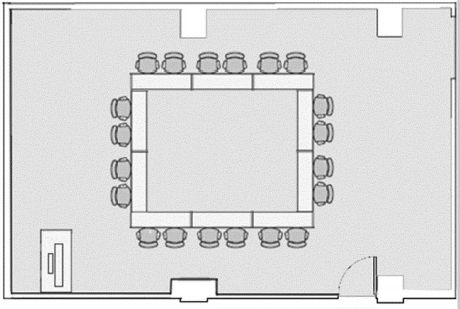

Tables in the Boardroom were set out as a single open box shape. We made use of the narrow desks that had been in the room previously, where they had been set in rows. Immediately it became clear that the possibilities were quite limited. People sitting next to each other can converse and everyone can pay attention to the facilitator touring the room, but every interaction required the participants to turn. Even people sitting opposite each other would have to shout to be heard.

Figure 12.1 The Boardroom

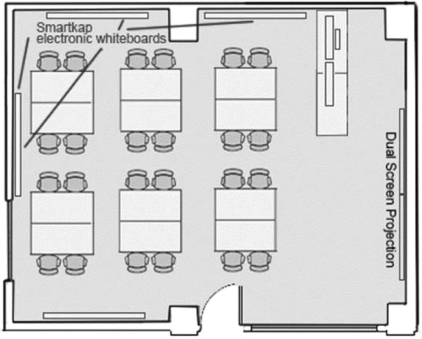

Figure 12.2 The Project Studio

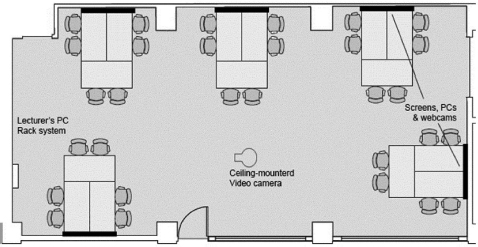

Figure 12.3 Media-enhanced team-based learning

The seating plan itself, proposed to model formal meetings for employability purposes, had little learning value. The room started to make sense, however, when the facilitator set problems. Groups, defined by the four sides of the box, could swivel their chairs around to the whiteboards and the constraint of the layout was immediately released as the groups set to work on writing or drawing-based problem activities. Whiteboard photographs, animations and video commentaries of concept maps were made using smart devices.

In the Project Studio, dual projectors could present information from two sources side-by-side. Again, whiteboards lined the walls, and additional SmartKap boards were installed to capture drawings to personal devices. This time the desks were laid out in six large islands surrounded by plenty of floor space to give project groups space to browse their whiteboard work. All of the rooms featured light, stackable chairs which made it easy to use or dispense with them. In this case the large groups organised themselves around table-based tasks using flip chart paper, spreadsheet data, or other sources of information brought into the room by the project teams, their tutor, or a guest. All rooms had digital visualisers and in the Project Studio information, objects or drawings created at earlier project stages could be presented alongside current work to show progress for self-reference or to external participants such as employers or clients for authentic feedback.

The cost of acoustic treatment, microphones, video cameras, mobile whiteboards, and multiple-screen projection made the installation of the Media-Enhanced Team-based Learning room more expensive, but it was still put together within the normal refurbishment budget by reconfiguring existing furniture. Acoustics were further controlled using mobile whiteboards, one side of which was covered in green screen textiles so that teams could produce overlay backgrounds on the videos they produced. A ceiling mounted video camera, capable of following movement, was installed for capturing role play or performances.

Our main challenge came from various people persistently reorganising the room into rows. This was due to the limitations of the institution’s timetabling system to specifically target and timetable ‘trained’ academics, the regular use of the high-profile rooms for non-teaching events, and because cleaning staff struggled to accept the design or follow the laminated instructions I posted to describe the layout! The opportunity to develop the space was fortuitous, but it became evident that our original request to maintain the space and offer a continuous programme of CPD through a continual staff presence was critical.

However, we learnt a lot and this work led to me developing a Flexible Classroom Policy that committed the University to a default of cabaret style settings for all pool classrooms, and etiquette for leaving classrooms in a good state and reporting breakages.

Analysis and discussion

Three themes are explored through the following analysis of the vignettes that reflect the need for change in the management and pedagogic adoption of active learning.

Space or place

The first vignette introduces the conundrum of needing to create space and manage its maintenance while not being able to predict its meanings as a locus of personal and communal academic endeavour; its sense of academic place. This conundrum is evident in all the vignettes in different ways.

The collaborative development of the Typology aimed to address this conundrum. On reflection, the challenge of producing it came from attempting to map the active learning as a lived experience (place) to a formal conception of its use (space).

In the third story, the idea of place is central in the idea of the conversational learning walks. Conversation epitomises the idea of active learning in spatial terms: walking and talking is a means of creating place and identity through the act of goal-orientated and open-ended learning.

Similarly, in Stand-Up Pedagogy, the physical space is devoid of the typical bland constraints that usually interfere with the natural inclination of people to interact and think together communally. This contrasts with a space like SCALE-UP, for example, where special fixtures (tables, repeater screens, etc.), people and problems, create a special sense of structured place in which the facilitator and learners value navigating and negotiating their learning.

In the fifth story, a series of active learning rooms is created. While some rooms worked better than others, overall the outcome of the experiment confirmed that the configuration of a space directly shapes and informs our understanding of, and readies us for, active learning. If place is understood as space in which a learner can shape their own response to a dynamic situation and active learning is defined by its accommodation of challenging possibilities, space and place need to be at the forefront of thinking about the design of active learning. In effect, the space creates a scaffold of possibilities.

Navigating strategy and opportunities

The second theme explores the tension between strategic direction and emerging opportunities in educational development and active learning.

The story began by recognising and grasping the opportunity to challenge assumptions about the ‘new build’ project. It turned out that my intervention to represent the pedagogic perspective was welcome. My colleagues knew what they did not know, but not how to involve the pedagogic voice in what they perceived to be the mundane matter of facilities development. They had assumed that academics are experts in pedagogy and leaders in academic innovation and were unaware of inhibitors to academic innovation including role, experience, future outlook, time and process.

Creating a typology explicitly valued the diverse perspectives, experience and professional qualities of the mixed stakeholder group. Its production was opportunist, establishing a common ground for learning about spatial complexity together.

Using devices to facilitate conversation is also an important dimension of active learning. A walk is a device designed to foster serendipity through shared and overheard conversations. It is formal and strategic in its planning, but otherwise informal and opportunistic in its execution. Walks are intrinsically deviant in their learner-centredness, implicitly encouraging boundary-crossing behaviours being loosely scaffolded around the use of viewpoint stimuli. A schedule of questions on a theme coupled with landmarks establishes enough of an active learning space for challenging individuals and their co-walkers.

As with learning walks, active learning in Stand-Up Pedagogy is loosely framed by the device of the space: a room containing only people, pens, problems, purpose and a sense of place. While the intended experiment could be said to have failed due to practicalities, the outcome of the Stand-Up Pedagogy experiment was a deeper understanding of active learning as co-production through loose scaffolding, and its impact was on the design of other facilities.

Perhaps the most salient outcome of exploring the tension of strategy and opportunity is revealed in the exploitation of the 5-year refurbishment cycle as a basis for developing the active learning classrooms. We proved a lot can be achieved through simple reconfiguration and academic support.

An opportunity emerged from all of these vignettes, and other innovations, as they revealed examples of transition, liminality, boundary crossing and connectivity, thereby disrupting binary conceptions and perceptions of space. Opportunities are made, so in all these stories agency, trust and co-operation play a key role.

Using co-production to address complexity

Finally, the development of active learning spaces requires an ethos of co-production. The story begins with the problem of a lack of effective conversation in which the self-defeating use of jargon and indecipherable plans reinforces organisational divisions; a point also demonstrated in the second story in which the act of co-producing the Typology was as valuable as the Typology itself. It led to a professional trust that became powerful later in our collaborations.

Learning walks, in the third vignette, epitomise co-production. Walking and talking together involves a natural flow of people weaving in and out of conversation in ways that create rich possibilities and understanding. Learning walks, therefore, can be thought of as an organic form of active learning. Having just a few waymarks along with some common knowledge, interest, curiosity and purpose is enough to scaffold a deep learning conversation.

Stand-Up Pedagogy and white-boarding are co-productive forms of active learning in which learning is an outcome of people, pens, problems, purpose and place.

In the final vignette, each of the rooms was conceived to promote co-production as a basis for learning. In all cases, co-productive activities were achieved, although the Boardroom configuration demonstrated how easily co-production is disrupted by inadequate seating. The whiteboards in each of the rooms, however, proved how students can learn by physically writing and drawing together as the basis for forming understanding by ‘working out’ their thinking together through their collective representation of knowledge and ideas.

Conclusion

Effective active learning spaces embody a sense of place in which a co-operative ethos is a prerequisite for successful learning. Active learning is scaffolded through the provision of enough structure to support individual and collective self-direction, which is often both goal-oriented and open-ended. Knowledge is complex, interpreted and ecological, yet traditional learning systems cannot easily accommodate difference and may be responsible for the struggle that some students endure. An active and co-operative learning space, however, is intended to be learner-centred, accommodating different values, motivations and ecologies more easily.

As with active learning, the vignettes show how the complexity of designing spaces for learning is best resolved through co-production in which conversation supports rich, imaginative thinking.

Recommendations for the development of active learning space

- In learning space development, ensure that the value of all stakeholders is accommodated through an ethos of co-production and purposeful conversation.

- Ensure the academic voice is present, informed and a leading influence on the design of spaces for learning.

- Situate development as a strategic matter requiring ongoing investment through alignment to the business priorities for learner engagement and retention, and the need to address outcomes relating to the future graduate.

- Be clear about the meaning of flexibility in the design of active learning space and how incorporating just enough structure can facilitate both goal-oriented and open-ended learning at the same time.

- Model active learning and space in academic and professional services CPD programmes.

- Design for the dynamic and pedagogic rhythm and flow that distinguishes active learning.

References

Atkinson, P. and Reed-Danahay, D. (1999) ‘Auto/ethnography: rewriting the self and the social’. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 5 (1), 152.

Beichner, R. (2008) The SCALE-UP project: A student-centered active learning environment for undergraduate programs. An invited white paper for the National Academy of Sciences, September 2008. Online. http://physics.ucf.edu/~bindell/PHY%202049%20SCALE-UP%20Fall%202011/Beichner_CommissionedPaper.pdf (accessed 10 April 2019).

Bloor, M. and Wood, F. (2006) Keywords in Qualitative Methods. London: SAGE Publications.

Boys, J. (2011) Towards Creative Learning Spaces: Re-thinking the architecture of post-compulsory education. London and New York: Routledge.

Butz, D. and Besio, K. (2009) ‘Autoethnography’. Geography, 3 (5), 1660–74.

Haigh, N. (2005) ‘Everyday conversation as a context for professional learning and development’. International Journal for Academic Development, 10 (1) 3–16.

James, J. (2015) ‘Autoethnography: a methodology to elucidate our own coaching practice’. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring, Special 9, (June 2015).

Middleton, A. and Spiers, A. (in print). ‘Learning to twalk: An analysis of a new learning environment’, in C. Rowell (ed), Social Media in Higher Education: case studies, reflections and analysis. Open Book Publishers.

Monahan, T. (2002) ‘Flexible space and built pedagogy: Emerging IT embodiments’. Inventio, 4 (1), 1–19. Online. http://www.torinmonahan.com/papers/Inventio.html (accessed 10 April 2019).

Oldenburg, R. (1989) The Great Good Place: Cafés, coffee shops, community centers, beauty parlors, general stores, bars, hangouts, and how they get you through the day. New York: Paragon House.

SCHOMS, AUDE and UCISA (2016) The UK Higher Education Learning Space Toolkit: a SCHOMS, AUDE and UCISA collaboration. Universities and Colleges Information Systems Association. Online. http://www.ucisa.ac.uk/learningspace (accessed 10 April 2019).