1 SCALE-UP at Nottingham Trent University: The adoption at scale of an active learning approach for diverse cohorts

Jane McNeil and Michaela Borg

Introduction

This chapter focuses on strategies to adopt Active Learning (AL) at institutional scale. There are several reasons why a strategic approach might be needed to expand the use of a highly regarded pedagogic approach, widely discussed, and with evidenced benefits (Freeman et al., 2014; Inge, 2018).

Firstly, AL is such a loosely-defined and widely-used term as to be rendered almost meaningless in terms of shared understanding of approach (Balz, 2018). This presents challenges for understanding its prevalence or assessing its benefits for students in any given context, and in addition, the rationale for its use is rendered opaque to students.

Secondly, AL techniques are observable at the level of classroom practice, but less so in terms of module and programme design. This tactical deployment might be unproblematic, except that it can present challenges in understanding how these pedagogies are supported within a programme team’s repertoire. For example, how they are used across and between levels of study, how they can be assessed for efficacy beyond the immediate context, and how their use relates to the overall learning, teaching, and assessment strategy of a programme.

Programme leaders comment that, for large cohorts of students, didactic approaches like lectures remain the dominant pedagogy, not because they are always preferred, but because of operational constraints and resourcing, which are often outside the programme team’s control.

The interest in creating learning environments that enhance learning and teaching has been widely discussed (Bothwell, 2015; Cotterill, 2015; McNeil and Borg, 2018). Although this is often described as a shift away from tiered lecture theatres towards flexible spaces to support a range of uses for collaborative, active and enquiry-based learning (EBL) approaches, the reality is less straightforward. Institutions face challenges in predicting and providing an appropriate range of learning and teaching spaces, in the right proportion, at the right time and location.

These considerations mean that, without planning and support, achieving and sustaining changes in pedagogy is challenging, whether for a single programme team, or an entire institution. Educational developers often share stories of pedagogic ‘lift and shift’, where investment in flexible spaces, engenders disappointment when the expected change in practice does not follow (see Brown, 2012). Similarly, lecturers share stories of being unable to introduce innovative pedagogies, because of space or organisational constraints (see Chism, 2002).

These challenges can be addressed by an institutional, strategic approach to AL adoption. The case described in this chapter used a community-based, voluntary and inclusive approach. This is not the only approach to educational change at scale, but it works well where programme teams are also engaged in their usual activities and where other institutional developments need attention. It affords academics control over the context for adoption, which is highly desirable not only as a principle, but also important in terms of achieving deeper and more sustainable change.

Desirable characteristics of a pedagogy for a strategic approach

An important consideration for a strategic approach is the choice of AL pedagogy. Selecting a specific approach has several benefits: it can be described and named, engendering higher confidence in a shared understanding. A supporting community can be developed around this, generating institutional visibility which aids discussions about resources needed to support programme teams.

The AL approach should be well-matched to the reasons for adoption, to the means and ends, with student learning and outcomes at the forefront. It should also accord with institutional values, or, if change to these values is sought, at least not be so far away as to be rejected.

It is also useful if the approach is already well-defined and well-described. A comprehensive framework and detailed guidance help lecturers adapting the pedagogy for their own context. Additionally, specifics about the design and practice of a given pedagogy are important in assessing its benefits (McNeil and Borg, 2018). Prince (2004) comments that the many ‘distinct approaches to [Problem-Based Learning] can have as many differences as they have elements in common’ (2004: 224) which creates a challenge in knowing which features afford benefit in a given context, and therefore which to use. Published evaluations of the approach in several settings are also useful for adoption, preferably using factors related to student outcomes (rather than only student satisfaction) and the same measures for comparability.

In addition, many perfectly sound educational developments are never adopted beyond the original innovators because they are simply unfeasible outside that context, or at scale (Serdyukov, 2017; Taylor, et al., 2018). A degree of pragmatism is needed in assessing whether an approach can be adopted given factors such as staffing, estate, timetabling, and contact time, and what might need to change to accommodate an approach at scale. These considerations should be evaluated alongside pedagogic efficacy when trialling approaches.

SCALE-UP

SCALE-UP (Student-Centred Active Learning Environment with Upside-down Pedagogies) is an AL approach pioneered by Professor Robert Beichner at North Carolina State University (NCSU, 2011). Originally developed in Physics for Engineering students, SCALE-UP has been adopted in many disciplines, by over 200 institutions worldwide (Beichner et al., 2007). It integrates educational approaches in a novel way and combines pedagogy with a distinctive learning space design. Teaching is flipped ‘upside-down’, with conceptual material encountered outside the classroom, and class time devoted to discovery and application of ideas. Students may be involved in teaching their peers while the lecturer facilitates, asking questions and sending one team of students to help another. Students receive frequent formative feedback from peers and the lecturer. The classroom space is designed with round tables, shared whiteboards and laptops to facilitate discussion and group activity.

SCALE-UP is described in scholarly literature (Beichner and Saul 2003; Beichner et al., 2007; Gaffney et al., 2008). Table 1.1 summarises those features documented in the literature using the authors’ descriptive framework (McNeil and Borg, 2018).

It is therefore a highly accessible approach to adopt. There are also several published evaluations of the approach in different institutions (Prince, 2004; Dori and Belcher, 2005; Freeman et al., 2014; Foldnes, 2016) that use the same factors as Beichner et al. (2007), who found that students’:

- Ability to solve problems was improved

- Conceptual understanding was increased

- Evidenced better attitudes to study

- Failure rates were reduced

- Benefits were sustained in subsequent programmes

Beichner et al. (2007) also found that use of SCALE-UP addressed unexplained disparities in attainment for students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Overall, therefore, SCALE-UP is a good candidate for adoption, because it is a mature approach that is well-described, its benefits have been evaluated in different contexts, and a blueprint exists for space design and technology, as well as pedagogy.

|

A: Approach Overarching approach of the teacher or teaching team |

A1 Draws on Physics Education Research, Workshop Physics, Studio Physics, Peer Instruction, Interactive Lecture Demonstrations. |

| A2 Intention to ‘facilitate active, collaborative learning in large classes’ at two universities. | |

| A3 Agenda to improve outcomes for introductory, calculus-based physics for engineers, by making changes to curriculum, pedagogy and ‘classroom environment’. Space and pedagogy redesigned together, over several iterations. |

|

|

B: Design Planning decisions for learning and teaching |

B1 Highly structured design begins with defining ‘instructional goals’ for each class (objectives/outcomes). This is contrasted with limiting plans to topic coverage. Class sizes of 50–100 students with 2–4 instructors (lecturers and teaching assistants). |

| B2 Students undertake conceptual learning before class and the class itself is based on a series of 5–15 minute segments of activities, interspersed with short plenary discussions of findings. Typical activities are problem-solving and conceptual understanding. The design of the learning space is a characteristic feature of SCALE-UP. Students sit at large circular tables and work in groups of 2–4, with identified roles and sharing access to computers and equipment. Students show work to peers and seek and give feedback. Group composition is based on prior performance; each is comprised of a student from the top, middle and bottom third of assessment rankings. Students complete more challenging follow-up problems after class, to practice and to deepen their understanding. Detailed rubrics are used for grading lab reports. |

|

|

C: Practice Tactics and strategies in the classroom |

C1 Several Classroom management procedures appear significant in the success of the approach: Groups operate on contracts and there is a (rarely used) protocol for ‘firing’ members. Instructors find they get better at timing the tasks and managing the class with experience. |

Introducing SCALE-UP at Nottingham Trent University

Nottingham Trent University (NTU) was the first UK university to pilot SCALE-UP in an institutional, multi-disciplinary project, beginning in 2012/13. There were several motivations for this including developing use of AL across NTU. Active collaborative approaches offer benefits for development of employability-related attributes such as group working, and problem solving (Prince, 2004). Approaches related to EBL can share benefits associated with those pedagogies, such as encouraging curiosity and developing resilience. AL, therefore, aligns well with the goals of institutions like NTU, with its strong mission focus on access, social mobility and employability (NTU Strategic Plan). Thus promoting AL and supporting expertise is a major theme in educational development at NTU.

There were three main reasons why we decided to use SCALE-UP in a cross-institutional pilot study. First, the research underpinning the assertions of the benefits of SCALE-UP was persuasive. Beichner et al. (2007) presented data comparing the experience of 16,000 physics students at NCSU, and considered benefits in terms of learning outcomes, rather than simply student satisfaction. Further evaluations have been conducted in other institutions resulting in a convincing body of comparable evidence (Dori and Belcher, 2005; Beichner, 2008; Gaffney et al., 2008).

The second reason was the appeal of EBL. Many benefits have been reported for EBL approaches (Healey and Jenkins, 2009; Spronken-Smith and Walker, 2010), but, although EBL has a long history, for many lecturers and students it represents a new technique. SCALE-UP can function as an accessible introduction to EBL: assisting lecturers making a transition from didactic and discursive forms, and scaffolding students’ enquiries. SCALE-UP can draw on a number of EBL modes, from closed problems to more open enquiry. However, under Levy’s (2009) conceptual framework, SCALE-UP largely operates in the staff-led domains of identifying and producing. Nevertheless, the challenge of using EBL methods with large cohorts is that it can be expensive, whereas SCALE-UP can be used successfully in class sizes of around 100.

This potential of SCALE-UP for use in large classes presented a third opportunity. In many HE institutions, lectures continue to dominate as the mode of large group teaching. NTU programme leaders frequently suggested that the substantial use of lectures was not always because it was the preferred way of teaching, but because spaces for large groups tended to be built to accommodate that type of teaching. SCALE-UP offered the opportunity to challenge the dominance of lectures, change the assumptions around space design for large groups, and, perhaps, to disrupt didactic modes of teaching.

Lecturers who volunteered for the pilot reported similar motivations, alongside other interests. The most frequent reasons cited in interviews included:

- Lectures were perceived to be ineffective

- Wishing to use technology in the classroom

- Attracted by the SCALE-UP rooms

- Opportunity to further develop EBL

- Student engagement

- Trying a new teaching approach

- Opportunity to teach the whole cohort

Hence SCALE-UP provided a focus for an institutional project around learning and teaching. From the start there was an ambitious and deliberate plan to pilot at scale and to use a strategic approach that included an extensive evaluation to build a case for further development.

Strategic pilot to wide-scale adoption

The appeal of the SCALE-UP approach was useful both in securing institutional agreement to pilot it, and the subsequent expansion.

Stage 1: Start up and pilot study, 2012/13

There are many ways to introduce a pedagogic development, with different degrees of formality, including sharing good practice and hoping for adoption, small-scale experiment and roll out, professional development programmes, and policy mandates. For SCALE-UP, we decided on a one-year pilot to test its benefits and to evaluate its feasibility in business terms. It was a highly visible project, working only with volunteers, with a goal of 30 lecturers from as wide a spread of disciplines as possible. We judged this would improve the chance of adoption spreading afterwards, and allow assessment of the approach in different disciplinary contexts. We were aware this approach carried increased risk and created challenges for evaluation. However, the limitation in more risk-averse approaches is that they often are not taken up, are not sustained, or fail to jump from initial development to wider adoption (Taylor et al., 2018). Our goal was to start a movement as well as trial a pedagogic approach.

In the event, we recruited academics on 37 modules, in Levels 4 to 7, across seven schools and 13 subjects: Art and Design, History, Education, Law, Sociology, Social Work, Criminology, Computer Sciences, Business Studies, Forensic Microbiology, Sports Science, Physics, and Academic Literacies.

We used a collegial approach to recruitment, development and evaluation, with town meetings to plan, agreements on data sharing and ethics, workshops to learn the approach, and support from educational developers throughout. The latter initially extended to in-room support. We also decided on an inclusive approach and support any way that a lecturer wanted to introduce SCALE-UP. Thus a variety of contexts and practices could be accommodated and it was hoped that this would encourage wider participation in the project, allowing colleagues to experiment with the approach to the extent that they deemed appropriate. This meant, for example, that while some pilots converted their whole module, others used SCALE-UP in selected sessions only.

Consequently, four classrooms were re-designed to create two SCALE-UP spaces, featuring large, round tables, which support collaborative working and create an egalitarian feel and a less formal atmosphere (Gaffney et al., 2008). Circulation space and lines of sight are also important, given that one lecturer works with up to 100 students. Each group was provided with laptops and portable whiteboards, and each room also had two or three displays with screen-casting facility (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 SCALE-UP room at NTU

Evaluation of the pilot

Given that many of the US studies focused on STEM subjects, the institution-wide evaluation assessed whether SCALE-UP would transfer to a UK context, and tested its efficacy across disciplines. The potential and feasibility for expansion of SCALE-UP were also assessed, along with the conditions needed for successful adoption, such as teaching strategies, resources, equipment, rooming and scheduling.

Evaluation design decisions were influenced by the context of the pilot as generating data across so many modules required a high level of coordination, for example, despite a limited budget. Wherever possible, therefore, we used data which were generated for other purposes. Furthermore, the inclusive approach to recruitment meant that there were mixed approaches to the use of SCALE-UP. We therefore developed a typology to identify and group modules:

- ‘SCALE-UP lite’ indicated that the module tutor(s) adhered to the core principles of SCALE-UP and followed most, if not all, of the characteristics of the approach. All of the year-long modules were described in this way.

- ‘SCALE-UP hybrid’ denoted modules that adopted all the principles and most of the characteristics of SCALE-UP, but did not use the approach in all sessions; thus other principles of learning and teaching influenced teaching on the non-SCALE-UP sessions.

The half-year modules taking part in the project were quite evenly split between SCALE-UP lite and SCALE-UP hybrid. No modules in the first year of the project committed to full SCALE-UP throughout the entire module.

Overall, the findings were cautiously positive. Evidence suggested that conceptual understanding was improved through engagement with SCALE-UP, attributed to higher levels of interaction between peers, the opportunities to ask questions, and greater engagement with learning materials. Most pilot module leaders and students were positive about the impact of SCALE-UP on students’ problem solving abilities. In contrast to US studies, which found that attendance averages were improved (Beichner, 2008), NTU attendance data did not indicate any difference from non-SCALE-UP modules. Module tutors judged that factors influencing attendance (either positively or negatively) were largely similar for SCALE-UP and non-SCALE-UP modules.

Student satisfaction data for the SCALE-UP modules were positive with high module satisfaction ratings. However, in detailed feedback students reported mixed views of SCALE-UP, with strikingly polarised reactions, particularly to group-work.

For overall grades, a comparison suggests that SCALE-UP did have a positive effect on attainment. More than half of the modules saw a notable improvement in grades in comparison to the previous year. However, no conclusions for failure rates could be drawn from this study due to limited comparative data.

Module tutors reported that preparation for SCALE-UP teaching took longer than anticipated in many cases, as it required the rethinking of module content and redesign of activities and resources. Some colleagues felt this was a useful opportunity to reflect on their practice.

In general, the technology was used as envisaged, with each group of three students sharing a laptop to find information, view learning resources, create material, and present their work. Students also brought their own devices.

The pilots allowed identification and resolution of challenges associated with combining multiple technologies and multiple users, and the screen-casting system, for example, was refined over several iterations. SCALE-UP produced a noisy classroom environment and voice augmentation provided for lecturers was later extended to students.

Lecturers and students identified the rooms as one the greatest benefits of the project, describing them as inspiring spaces and highly useful for collaborative learning. The room layout, and the round tables, allowed lecturers to engage with students more easily than in traditional rooms. The small whiteboards were also considered very useful, and were used by students in creative and problem-solving activities, and for presenting to the class.

Some comments from module tutors included:

The main thing with SCALE-UP is capturing how students learn, because I think years and years of evidence have shown us that students don’t learn the way we teach so what we need to do is start teaching the way they learn and that’s what SCALE-UP does

[B]eing able to interact with students is better than just standing in front of them talking, and it did really reinforce that, particularly going back into the lecture theatre … I have been trying to keep some of the principles

I have turned the curriculum upside-down

And from students:

At first I did not like [it] but as time went on I enjoyed it and [it] always kept people engaged

I would have preferred to have a more traditional lecture

I like that I am not just spoken to for an hour and that’s it

I feel more enthusiastic coming to these sessions

Stage 2: Expansion

The pilot was judged a success, not simply because the evaluation findings were sufficiently encouraging to gain institutional support to continue, but also because the project had generated widespread positive feeling about SCALE-UP. After the first year, adoption expanded quickly, and more SCALE-UP rooms were built, with demand often outstripping accommodation.

This success can be attributed to several factors:

- The impetus started with the pedagogy: we selected one that was right for the institution at that time, and we confirmed academic colleagues’ interest in it, before proceeding.

- We were relentless in promoting the project: attending committees, sending newsletters, talking about SCALE-UP everywhere. As part of this drive, Robert Beichner was invited to speak, and we invited academic and professional service decision-makers to meet him. He also hosted workshops for the project participants.

- There was genuine support from senior leaders, the Library, Estates, Information Services, Timetabling and Academic Administration.

- We changed both business process and pedagogy.

- We evaluated both operational feasibility and educational outcomes and ensured the evaluation report was circulated to all stakeholders.

- We provided considerable support for academics.

- We used a community approach, with voluntary participation, and many opportunities to share ideas. This created a peer support network for SCALE-UP and also established good conditions for sustainable educational change.

These factors are very similar to those identified in a review of 21 successful SCALE-UP implementations in the US (Foote et al., 2016). These authors reported ‘enabling factors’ including administrative support; being able to evidence success; funding for room modification, teaching resources and staffing costs; interacting with and visiting other, more experienced SCALE-UP users; a start-up team with multiple members; a culture that supports active teaching; enthusiastic champions; and, educational development support.

The evaluation identified pedagogic and operational considerations for expansion. For example, further guidance for new adopters was developed, initially around preparing students for SCALE-UP, group management and assessment design, which was then developed into a full handbook (McNeil et al., 2017). Operational adaptations were made, particularly regarding room and technology specifications, and academic workload planning.

A significant benefit of the project has been developing the dialogue between different support departments around learning spaces, and a general raising of the level of understanding about how teaching rooms shape and influence pedagogy. This has inspired a major change to the assumptions for planning the estate, and what Fisher and Newton (2014) described as ‘next generation learning environments’, are now routine features of teaching and study spaces. There has also been a marked increase in interest in related pedagogies such as flipped learning and enquiry approaches. To develop this interest, we supported an institution-wide project encouraging staff to increase student interaction in lectures.

This project aimed at influencing ‘mainstream’ practice for large group teaching and capitalised on the success and enthusiasm for pedagogic innovation that followed in the wake of SCALE-UP. In managing the growth in SCALE-UP alongside the development of suitable estate, we experimented with the use of SCALE-UP teaching strategies in non-SCALE-UP rooms, and the use of ‘pop-up’ SCALE-UP rooms (i.e., hybrid spaces which are set up to mimic a SCALE-UP space on some days of the week). These tactics and their wider benefits are reflected in Knaub et al.’s (2016) discussion of variations in space design in SCALE-UP in US classrooms, which they term ‘productive customisation’ (2016: 20). Similarly, Soneral and Wyse (2017) compare the impact on student grades and satisfaction of a classic room with a ‘mock up’ or low-tech version, finding little difference.

Scaling up even further

For the four years following the initial pilot (i.e. 2013/17), adoption of SCALE-UP at NTU increased organically year-on-year. We maintained a high profile and invited interested colleagues to contact us. An opportunity for a more strategic approach to growth arose in 2017 from a government-funded project to adopt at scale approaches which smaller studies had shown to address barriers to student success. With partners University of Bradford and Anglia Ruskin University, the Scaling Up Active Collaborative Learning project (2017/19) undertook further expansion of SCALE-UP alongside an evaluation of the efficacy of the approach to address unexplained disparities in student progression. The strategy for wider adoption focused on programme-level adoption. The rationale was based on our experience that the most successful SCALE-UP work occurred when a course team worked together to plan and implement the approach on several modules (rather than in isolation), as part of a programme-wide learning and teaching strategy. There were several challenges in our existing, collegial approach to expansion of SCALE-UP. From the beginning, we suspected that SCALE-UP adopters tended to be those innovative colleagues, who had a good understanding of pedagogy, and were already receiving positive feedback from students. As adoption expands, individual lecturers might need more support. Increasing demand on support that wider adoption requires is a significant consideration and required a move from a bespoke approach, to creating workflows and an end-to-end process that is more manageable at scale. This change represents a considerable cultural shift for educational developers.

Andrews et al. (2011) investigated the impact of AL when used by ‘typical instructors’ rather than education specialists, and reported that it cannot be assumed that the use of AL is itself going to result in learning gain as some practice may be ineffective. Our 2012/13 pilot found that colleagues’ use of SCALE-UP showed considerable variation. Currently we are investigating the impact of the ‘breadth’ and ‘depth’ of adoption, and the influence of practitioner experience. So, for example, we are analysing the extent to which a set of identified SCALE-UP components is used in a module, and the number of SCALE-UP sessions used across a module. Together with student feedback, these data should help us to gain a nuanced picture of SCALE-UP use.

Characterised from the beginning by a strategic approach to recruitment and awareness-raising and a collegial approach to development and engagement, SCALE-UP at NTU has grown substantially from a pilot of 37 modules to large-scale adoption, whereby around fifty per cent of programmes use an element of the approach.

Pedagogic innovation: factors in widespread adoption

The SCALE-UP project at NTU is different from many educational development projects in two main ways:

- It has been institution-wide from the start: many developments around pedagogy never make it beyond one or two subject areas

- There are lots of examples of universities developing new spaces for learning and teaching, but not seeing changes in teaching practice subsequently

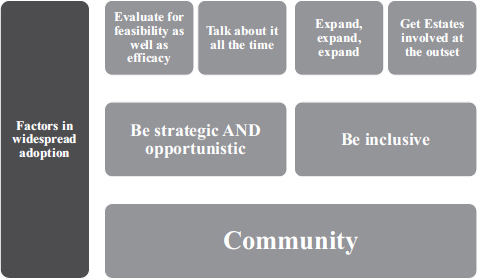

Figure 1.2 shows the model we used for the wide-scale adoption of a SCALE-UP at NTU.

It is crucial to develop a community of staff and students around the innovation, and while it is easier to engage colleagues if the approach is inclusive, it is important to understand how it is being adopted and adapted in different disciplines. A typology of use can help both dialogue around educational development support and evaluation. Evaluation is crucial and must address business feasibility as well as educational benefits of use, to engage colleagues from different areas of the university, and different levels of seniority. Evaluation is central to building a case for the impact, and to getting the message out into the broader university community. This engagement should be expansive, and include academic colleagues, the Students Union, colleagues in Estates, Timetabling, and Information Systems, for example, and, as SCALE-UP has a particular classroom design, early engagement of colleagues in Estates is crucial.

Figure 1.2 Model for wide-scale adoption of a pedagogy: SCALE-UP room, NTU (McNeil, 2018)

An important element of maintaining momentum and achieving widespread adoption of SCALE-UP is to continually expand and recruit new lecturers. At NTU, this involved working with Timetabling to create a process around identifying colleagues who might want to do SCALE-UP and then getting them into the right room. As we have grown, we have also worked with tutors to adapt SCALE-UP to work in a wider range of contexts and spaces. This helps community building and balancing estate development need versus availability. In addition, we have generated spin-off projects including using AL in lecture rooms with over 100 participants. In other words we have been both strategic and opportunistic in developing SCALE-UP at NTU.

References

Andrews, T.M., Leonard, M.J., Colgrove, C.A. and Kalinowski, S.T. (2011) ‘Active learning not associated with student learning in a random sample of college biology courses’. CBE-Life Sciences Education, 10 (4), 394–405.

Balz, D. (2018) The World Language Teacher’s Guide to Active Learning Strategies and Activities for Increasing Student Engagement. Second Edition. London and New York: Routledge.

Beichner, R.J. (2008) ‘The SCALE-UP project: A student-centred active learning environment for undergraduate programs’. Commissioned Paper, National Science Foundation. Evidence on Promising Practices in Undergraduate Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) Education Workshop 2, Washington DC, October 13–14, 2008. Online. http://sites.nationalacademies.org/dbasse/bose/dbasse_080106 (accessed 4 March 2016).

Beichner, R.J. and Saul, J.M. (2003) Introduction to the SCALE-UP (student-centered activities for large enrollment undergraduate programs) Project’. Proceedings of the International School of Physics, Varenna, Italy. Online. http://www.ncsu.edu/per/Articles/Varenna_SCALEUP_Paper.pdf (accessed 9 December 2018).

Beichner, R.J., Saul, J.M., Abbott, D.S., Morse, J.J., Deardorff, D.L., Allain, R.J., Bonham, S.W., Dancy, M.H. and Risley, J.S. (2007) ‘The Student-Centered Activities for Large Enrollment Undergraduate Programs (SCALE-UP) Project’. Reviews in Physics Education Research, 1 (1). Online. http://www.per-central.org/items/detail.cfm?ID=4517 (accessed 9 December 2018).

Bothwell, E. (2015) ‘Lecture theatres should be ditched for ’21st-century teaching spaces’’. Times Higher Education, 15 October 2015. Online. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/lecture-theatres-should-be-ditched-21st-century-teaching-spaces (accessed 9 December 2018).

Brown, J.S. (2012) ‘Learning in and for the 21st Century’. Symposium and public lecture. National Institute of Singapore, 21–22 November 2012. Online. http://www.johnseelybrown.com/CJKoh.pdf (accessed 9 December 2018).

Chism, N.V.N. (2002) ‘A tale of two classrooms’. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 92, 5–12.

Cotterill, S.T. (2015) ‘Tearing up the Page: Re-thinking the Development of Effective Learning Environments in Higher Education’. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 52 (4), 403–13.

Dori, Y.J. and Belcher, J. (2005) ‘How Does Technology-Enabled Active Learning Affect Undergraduate Students’ Understanding of Electromagnetism Concepts?’ The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 14 (2), 243–79.

Fisher, K. and Newton, C. (2014) ‘Transforming the twenty-first-century campus to enhance the net-generation student learning experience: Using evidence-based design to determine what works and why in virtual/physical teaching spaces’. Higher Education Research & Development, 33 (5), 903–20.

Foldnes, N. (2016) ‘The flipped classroom and cooperative learning: evidence from a randomised experiment’. Active Learning in Higher Education, 17 (1), 39–49.

Foote, K., Knaub, A., Henderson, C.R., Dancy, M. and Beichner, R. (2016) ‘Enabling and challenging factors in institutional reform: the case of SCALE-UP’. Physical Review Physics Education Research 12 (1)

Freeman, S., Eddy, S.L., McDonough, M., Smith, M.K. Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H. and Wenderoth, M.P. (2014) ‘Active learning boosts performance in STEM courses’. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111 (23), 8410–5.

Gaffney, J.D.H., Richards, E., Kustusch, M.B., Ding, L. and Beichner, R.J. (2008) ‘Scaling Up Education Reform’. Journal of College Science Teaching, 37 (5), 18–23.

Healey, M. and Jenkins, A. (2009) Developing undergraduate research and inquiry. York: Higher Education Academy. Online. https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/developing-undergraduate-research-and-inquiry (accessed 9 December 2018).

Inge, S. (2018) ‘Student satisfaction ‘unrelated’ to academic performance – study’. Times Higher Education, February 12, 2018. Online. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/student-satisfaction-unrelated-academic-performance-study (accessed 10 October 2018).

Knaub, A.V., Foote, K.T., Henderson, C., Dancy, M. and Beichner, R.J. (2016) ‘Get a room: the role of classroom space in sustained implementation of studio style instruction’. International Journal of STEM Education, 3(8).

Levy, P. (2009) Inquiry-based learning: a conceptual framework. Centre for Inquiry-based learning in the Arts and Social Sciences, University of Sheffield. Online. www.cur.org/assets/1/7/ISSOTL-Sheffield.pdf (accessed 9 December 2018).

McNeil, J. (2017) ‘Pedagogies without borders. Strategic adoption of teaching models across contexts, disciplines and cultures’. Advance HE Annual Conference, Teaching in the spotlight: Learning from global communities, 4 July 2018, Manchester, UK.

McNeil, J. and Borg, M. (2018) ‘Learning spaces and pedagogy: Towards the development of a shared understanding’. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 55 (2), 228–38.

McNeil, J., Borg, M., Kennedy, E., Cui, V., Puntha, H. and Rashid, Z. (2017) SCALE-UP Handbook. Second Edition. Nottingham: Nottingham Trent University.

Prince, M. (2004) ‘Does Active Learning Work? A Review of the Research’. Journal of Engineering Education, 93 (3), 223–31.

North Carolina State University (2011) ‘Scale-Up’. Online. http://scaleup.ncsu.edu/ (accessed 25 March 2019).

Office for Students (2017) Scaling Up Active Collaborative Learning for student success project 2017–2019: Addressing Barriers to Student Success programme. Online. https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/promoting-equal-opportunities/addressing-barriers-to-student-success-programme/nottingham-trent-university/ (accessed 17 December 2018)

Serdyukov, P. (2017) ‘Innovation in Education: What Works, What Doesn’t, and What to do about it? Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning, 10 (1), 4–33.

Soneral, P.A.G. and Wyse, S.A. (2017) ‘A SCALE-UP Mock-Up: Comparison of Student Learning Gains in High- and Low-Tech Active-Learning Environments’. CBE Life Science Education, 16(1), 1–15.

Spronken-Smith, R. and Walker, R. (2010) ‘Can inquiry-based learning strengthen the links between teaching and disciplinary research?’ Studies in Higher Education, 35 (6), 723–40.

Taylor, C., Spacco, J., Bunde, D.P., Zeume, T., Butler, Z., Bort, H., Maiorana, F. and Hovey, C.L. (2018) ‘Propagating the Adoption of CS Educational Innovations’. Proceedings of ITiCSE 2018, Larnaca, Cyprus, June 2018.