10 A tale from the north: Moving away from formal learning spaces to active learning spaces

Moving away from formal learning spaces to active learning spaces

Auðbjörg Björnsdóttir and Ásta Margrét Ásmundsdóttir

Introduction

This chapter gives a review of the transformational process of moving from formal lecture rooms to active learning classrooms at the University of Akureyri (UNAK) from 2014 to 2016. UNAK is located in the Northern part of Iceland, with approximately 2,000 students. It was established in 1987 to offer university education, encourage research, development and innovation in rural areas of Iceland, and to tackle the problem of ‘brain drain’. The University has been leading in the teaching of distance and campus-based students in Iceland for 20 years. In recent years, the University has moved towards flexible learning models, with the focus on shifting from traditional lectures to more flexible and innovative teaching and learning. The Centre for Teaching and Learning (TCTL) at UNAK, was established in 2015 to support this initiative, and one of their first projects was the creation of developmental classrooms, with the aim of turning them into active learning classrooms (ALCs) over time.

Our example of the process of moving from a formal classroom to an ALC, took place in a first-year course, General Chemistry, in the Department of Natural Resource Sciences. This course had high attrition of around 30 per cent, low attendance, a failure rate of 40–50 per cent, and low student satisfaction according to course evaluation. After the instructor had used ‘flipped classroom’ teaching for a year, student satisfaction increased compared to the previous year, but student attendance remained low. The failure rate on the final exam was still around 40–50 per cent. In this review, we address the different obstacles we faced in the process, the importance of using flexible classrooms, and the importance of cooperation with key faculty staff and students. Students taking the course were surveyed and the results related to the ALCs are reviewed.

Literature review

Active Learning Classroom (ALC) is the term often used to describe a student-centred, technology-rich learning environment at the University of Minnesota (2019). ALCs are a modification of the SCALE-UP room layout (Student Centred Active Learning Environment with Upside-down Pedagogies) (Brooks, 2011). The SCALE-UP project started as a reform movement in the 1990s at North Carolina State University (2011) to change the teaching of large introductory physics courses by reworking the layout and technology of the classroom where these courses were being taught. These new learning spaces consisted of round tables with laptop connectivity for students, and good access to lab equipment. In addition to restructuring the learning spaces, the pedagogical approach and teaching material were amended to facilitate cooperative learning, in-class problem solving, and increased instructor-student interaction (Beichner et al., 2007).

Other projects such as Technology Enabled Active Learning (TEAL) at MIT (2019) and Transform, Interact, Learn, Engage (TILE) at the University of Iowa (n.d.), plus the before mentioned ALC at the University of Minnesota, have been modelled on SCALE-UP (Baepler et al., 2014). Numerous evaluations of learning, using both substantial quantitative and qualitative data, have been conducted in parallel with the curriculum development and the classroom design efforts accompanying the SCALE-UP projects. The findings can be summarised as having shown an improvement in students’ problem-solving ability, an increase in students’ conceptual understanding, better student attitudes, and a significant reduction in failure rates, especially for females, minorities, and at-risk students, who generally do better in later courses (Beichner et al., 2007).

The ALCs at the University of Minnesota feature large round tables that can seat nine students; each table is linked to a panel display screen. Students can project content on to those screens from laptops located on their tables. There is an instructor station, from which instructors can display content via projector screens, and control the feeds to the student display screens. There are wall-mounted glass marker-boards around the perimeter of the room (ALC Pilot Evaluation Team, 2008).

A study at the University of Minnesota was performed where two sections of the same course taught by the same instructor were compared, the only difference was the learning environment for each section. The two different learning environments were an ALC and a traditional classroom. The results of the study showed that, when all factors, apart from the learning space, were kept constant, students in the ALC section outperformed students in the traditional classroom in terms of student learning (Brooks, 2011). The advantages of working in ALCs include increased learning gain and students reporting high satisfaction with the learning environment. However, these spaces can present some teaching challenges, including a room with no front or focal point; noise and other distractions that may impact individuals with certain learning disabilities; and a need for expertise in the technology.

Teaching in ALCs requires time, effort and, for some, a new approach in teaching. Teachers need to take the time to study the room because the setup is not traditional, and possibly reconsider their teaching methods to, for example, incorporate active learning into their teaching. Due to the lack of a front or focal point in the classroom, teaching that relies heavily on lecturing is not suitable for an ALC (Baepler et al., 2014).

These findings and the set up for the ALCs were considered in the designing of the UNAK’s ALCs.

Transformation process

The process of moving a traditional lecture room to an active learning classroom at UNAK, took around three years. This transformation began in 2014 when a teacher started to change the first-year mandatory General Chemistry course at the Department of Natural Resource Sciences, from traditional lectures to flipped learning. The reason for this change was that the course had around 30 per cent dropout, low attendance, around 40–50 per cent failure rate, and low satisfaction among students according to course evaluations. Flipping the classroom, as the name indicates, means that students study the course content at home, often by listening to lectures or watching videos that the teacher has submitted on the internet, and do the ´homework´ in class with support from the teacher. The time spent in class is spent entirely on problem solving activities and discussions. Students are engaged for the entire time, either as individuals or in groups, and the teacher has much more time to offer one-to-one support to individual students (King, 1993; Lage et al., 2000; Bergman and Sams, 2012).

During the first year of flipped learning in the chemistry course, few students attended, and therefore did not make full use of the learning material available to them. According to the course evaluation, student satisfaction increased significantly, but the failure rate was about the same as the previous year. Following this, the instructor started working with the newly established TCTL to improve the course, with the aim to increase student attendance, participation and learning. In the second year, it was therefore decided to change the assessment in the course from individualised to collaborative assignments in an attempt to improve these three factors. Students still had access to all the material beforehand and were invited to attend class to work on the collaborative assignment with the help of the instructor.

Before students came to the classroom, the setting of the room was changed from lecture-based to group-based. The tables were grouped together so that they could accommodate up to six students. The underlying notion was to give students a clear message of the collaborative group work that was expected to take place in the classroom as they entered. The instructor had to arrange the room before the class. During that second year, the instructor had to get permission to rearrange the room from the instructors that were teaching in the classroom before and after.

This change improved students’ attendance dramatically compared to the previous year, from less than 30 per cent to over 70 per cent of the campus-based students. The failure rate on the final exam for this second year of transformation was similar to the previous year at around 40–50 per cent. It is difficult to compare failure rate on the final exam between years in this course, as the final exam is not standardised.

As the change in classroom set up had resulted in such a positive effect on student attendance, the TCTL applied for changing the setup of the classroom to an ALC before the end of the second year. The Management Board at UNAK granted TCTL permission and funding to change the classroom to an ALC. The classroom was then modified by setting up six big tables, each with six chairs and by each table there was one 55-inch (140cm) panel screen and a whiteboard. There was also a projector and a teaching station located in the middle of the classroom with a computer for the instructor. During Fall 2016, before the start of the third year of the course, the ALC was setup and ready to use.

However, the process of changing the classroom was not initially supported by all university staff. The obstacles were institutional, conservative, and teacher-centred impacts. Institutional challenges included convincing supporting staff, especially those in charge of scheduling classrooms for academic staff, and custodial staff that the classroom was changing. Even though the permission to change the setup of the classroom had been granted, the cleaning staff would often arrange the classroom to the original setup, and classes with traditional lectures would be scheduled in the classroom. An example of the conservative teaching attitude at UNAK was that some academic staff thought it was a petty task to try to change the classroom, while others pointed out that classrooms at UNAK had always been that way (i.e. lecture-based), and therefore they should not be changed.

Progress was only made when the Managing Director at UNAK issued an email to supporting staff that announced that the classroom was now a flexible classroom overseen by TCTL. Nevertheless, during the first semester after the ALC setup, there were still requests to use the room as a lecture room. TCTL staff were firm on the ALC setup and that it could not be changed, and no exceptions were made. All scheduling of the classroom had to go through TCTL. Instructors could request to use the classroom, but the idea behind the ALC was then explained to them by TCTL staff, who discussed if their way of teaching really was adapted to the ALC idea. The fact that ALC is informed by research helped to convince some of the staff who were not sure why the TCTL had changed the classroom. Other staff who had been using active learning, and especially cooperative learning in their classes, were very accepting and supportive of the changes being made to the classroom. A list of faculty members from all three faculties at UNAK, who stated that they were willing to use the ALC, was crucial in convincing the Management Board to support giving jurisdiction over the classroom to TCTL. Figure 10.1 shows the classroom in 2014 and 2015 when it was still a traditional classroom. Figure 10.2 shows the room after its transformation to the ALC in 2016.

Figure 10.1 Classroom before transformation to ALC, 2014 and 2015

Figure 10.2 Classroom after transformation to ALC, 2016

Methodology

Two surveys were used to collect data from students in the General Chemistry course: pre- and post-instruction. The surveys were administered during the first semester after using the ALC in 2016 and then repeated in 2017. The pre-instruction survey was used to gather information on students’ personal status, scholastic preparation in the subject, attitude and expectations for the course. The post instruction survey gathered information on students’ experience of the different aspects of the course, their estimation of their own performance so far, and their experience with the ALC. The instruments used included 19 items for the pre-survey and 27 items for the post-survey, 16 of the items were the same for both surveys. The pre- and post-surveys were created in 2015 by the teacher and a TCTL staff member skilled in survey design. When ALC was used in the course, items were added to the post-survey to collect data on students’ perception of the use of ALC.

|

# |

Item |

Response Type |

|---|---|---|

|

1 The effect of ALC on: i. Interaction with the instructor ii. Interaction with other students iii. Group performance iv. Collaboration in the group v. Understanding on the course material vi. Engagement in class vii. Wellbeing in class |

5-point response scale: 1) Very positive effect 2) Positive effect 3) No effect 4) Negative effect 5) Very negative effect |

|

| 2 |

Please list positive and negative aspects regarding the ALC |

Open-ended |

| 3 |

How could the ALC be improved? |

Open-ended |

To understand student’s perception of the use of ALC, three questions on the post instrument were related to the ALC (see Table 10.1). The first question used a 5-point Likert scale (Very positive effect, positive effect, no effect, negative effect, very negative effect) to measure the effects the ALC had on seven areas of teaching. Two additional questions were open ended, one of which asked students to list positive and negative aspects about the ALC, and the other asked students to suggest how the ALC could be improved.

Findings

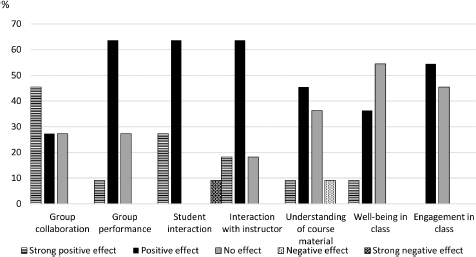

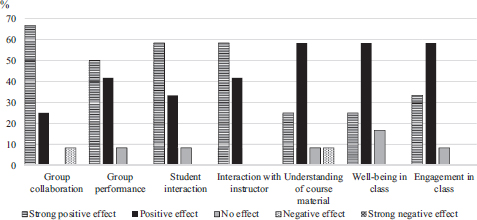

Figure 10.3 shows the results of the survey made at the end of the 2016 course. The total number of students in the class was 14 at the start of the semester, however two dropped out, and 11 of the 12 students who were still on the course participated in the survey, giving a response rate of 92 per cent. Figure 10.4 shows the results of the 2017 survey. The total number of students in the class was 22 at the start of the semester, however seven dropped out, and 12 of the 15 students who were still on the course participated in the survey, which resulted in a response rate of 80 per cent.

Figure 10.3The effect of the ALC on factors of teaching and learning (Fall 2016)

Figure 10.4 The effect of the ALC on factors of teaching and learning (Fall 2017)

Responses to the open questions were similar for both years. Students were asked to list positive and negative things regarding the ALC, most of the responses were short and positive, such as, “it’s perfect, no need to change it” or they mentioned that they liked the change that had been carried out within the room. Also, some students mentioned that it facilitated group work: “It is very good to have one ‘base’ for each group. It facilitates communication in a circle rather than sitting in two seats rows in a traditional classroom”. In terms of technology, students mentioned that the panel screens made it easier to observe calculations being performed in the classroom. There were two negative responses, one regarding the chairs in the room. The other one was about group members who did not attend, and therefore the students did not use the room as much.

The other open question asked how the classroom could be improved, but students did not make many suggestions. Some students said the chairs were uncomfortable, and others mentioned that a wider range of connections, like HDMI, should be available to connect to the panel screens. Other students noted that it was difficult to connect their laptops to the panel screens. Students also mentioned that the whiteboard should be used more by the groups and the teacher.

Discussion

The results from the survey for students taking the course in 2016 indicate that students experienced positive effects of the ALC in relation to communication between students, and also between students and the instructor. Additionally, the majority of students felt that the ALC environment had a positive influence on the efficiency of the group work. Some positive effects were reported in relation to collaboration in the group, wellbeing in class, students’ understanding and willingness to participate. The results from the same survey from students taking the course in 2017 show more positive effects of the ALC classroom than the year before. More than 50 per cent of the students reported very positive effects in relation to communication between students, and between students and the instructor, the efficiency of the group work, and the collaboration in the group. The survey also shows the positive effect regarding wellbeing in class, understanding and willingness to participate. Overall, the students reported a positive or very positive experience of ALC, with 2017 being more positive than 2016. However, this is not surprising since technology in the ALC had been improved by, for example, the addition of cables to connect to the panel screens for the second year.

The open responses from both the 2016 and 2017 surveys were positive, in that they highlighted how the ACL facilitates group work and overall students were satisfied with the changes made in the classroom. In addition, students were given the opportunity to criticise the change and to come up with suggestions for improvement in the classroom. Their short and positive responses indicate that they liked the changes made to the classroom and that they did not have any further suggestions or comments.

Conclusion

The results support the transformation from the traditional classroom to the ALC. Nevertheless, as Baepler et al. (2014) stated, teachers that use the ALC have to be prepared to allocate time and effort, and be ready to try new approaches. Instructors need to take the time to familiarise themselves with the classroom because of its non-traditional setup and embrace new opportunities that might require them to reconsider their teaching methods. The ALC is not suitable for delivering traditional lectures due to the lack of a front or focal point.

The transformation of the traditional classroom to an ALC, was an interesting journey that started in 2014 with a Chemistry instructor flipping her classroom and later adding collaborative assignments. The process was more challenging than expected, as there were technical problems, ongoing negativity from some of the teaching and support staff, an under-estimate of both the cost and the complexity, and it took longer than expected to set up the ALC. However, the importance of having data to support the utilisation of the ALC was instrumental in convincing the teaching and administrative staff to transform the classroom. Having collected our own data from those who have used the classroom in support of the usage of the ALC, will make it easier to continue with transforming more classrooms to ALC in the future.

The transformation of the traditional classroom to an ALC is only one of several pedagogical developments that have taken place at UNAK in recent years. This is part of the ongoing professional development for academic staff in adjusting their teaching styles to match the mode of flexible learning offered at the University.

The ALC supports and contributes to the flexible learning model offered at UNAK, and students can access learning material, and online content, and communicate with their teacher. On some occasions, however, students must come to campus to meet other students and the teachers. During these on-campus sessions it is important to practice active learning, and the ALC is ideal for that. The frequency of student visits to campus varies between departments and subjects, but in the case of Chemistry, students could attend class for active learning sessions almost every week.

Next steps and future planning

The next step at UNAK is to support and develop the ALC further, by adding more ALCs and develop this mode of study so it can also serve the students at a distance. That work has started with the addition to the Chemistry class, which allows distance students to participate in class via a telepresence robot called Beam® (Suitable Technologies, Inc., 2018). Beams have been used at UNAK, with both staff and students, since Fall 2017. The Chemistry teacher has, for example, participated in the ALC from Norway through a Beam. The use of Beams at UNAK opens up new and exciting opportunities for both staff and distance students who want to participate in the ALC.

Another project underway at UNAK is the use of portable ALC stations. The three portable ALC stations currently available at UNAK each include a stand with a panel screen with a computer, and an 80 x 120cm (31 x 47 inches) whiteboard. The present ALC can seat 36 students, but it would be ideal to increase this number to 60–70 students. The Nursing course at UNAK, for example, has 60 students. The idea is to transform the main hall, which can seat around 180 students, so that it can accommodate approximately ten portable ALC stations. The main hall already has portable tables and chairs, so should be easy to rearrange the tables to form the ALC arrangement.

The introduction of flexible learning, the transformation of a classroom into the ALC, and the use of telepresence robots, would not have taken place if it were not for the support of the Management Board at UNAK. The Management Board made the decision to offer financial support to flexible learning at UNAK in 2015, which led to the formation of the TCTL. The TCTL supports academic staff to adapt to more innovative teaching methods, and is responsible for the transformation of the learning spaces at UNAK.

References

Baepler, P., Brooks, D.C. and Walker, J.D. (eds) (2014) ‘Active Learning Spaces’, New Directions in Teaching and Learning, 137. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Beichner, R., Saul, J., Abbott, D., Morse, J., Deardorff, D., Allain, R., Bonham, S., Dancy, M. and Risley, J., (2007) ‘Student-Centered Activities for Large Enrollment Undergraduate Programs (SCALE-UP) project’, in E. Redish and P. Cooney (eds), Research-Based Reform Of University Physics, (1–42). College Park, MD: American Association of Physics Teachers.

Bergman, J. and Sams, A., (2012) ‘Flip your classroom: reaching every student in every class every day’. International Society for Technology in Education, 19–29.

Brooks, D.C. (2011) ‘Space matters: The impact of formal learning environments on student learning’. British Journal of Educational Technology. 42 (5), 719–26.

King, A. (1993) ‘From sage on the stage to guide on the side’, College Teaching. 41, 30–5.

Lage, M.J., Platt, G.J. and Treglia, M. (2000) ‘Inverting the Classroom: A Gateway to

Creating an Inclusive Learning Environment’. The Journal of Economic Education. 31 (1), 30–43.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2019) TEAL – Technology Enabled Active Learning. Online. http://icampus.mit.edu/projects/teal/ (accessed 10 April 10, 2019).

North Carolina State University (2011) Student Centered Active Learning Environment with Upside-down Pedagogies. Online. http://scaleup.ncsu.edu/ (accessed 10 April 10, 2019).

Suitable Technlogies, Inc. (2018) beam®. Online. https://suitabletech.com/ (accessed 10 April 10, 2019).

University of Iowa (n.d.) TILE. Online. https://teach.uiowa.edu/tile (accessed 10 April 10, 2019).

University of Minnesota (2019) Teaching in an Active Learning Classroom (ALC). Online. https://cei.umn.edu/teaching-active-learning-classroom-alc (accessed 10 April 2019).

University of Minnesota Active Learning Classrooms Pilot Evaluation Team (2008). Active learning classrooms pilot evaluation: Fall 2007 findings and recommendations. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota. Online. http://dmc.umn.edu/activelearningclassrooms/alc2007.pdf (accessed 10 April 2019).