11 Layers of interaction: Object-based learning driving individual and collaborative active enquiry

Object-based learning driving individual and collaborative active enquiry

Maria Kukhareva; Anne Lawrence; and Katherine Koulle

Introduction

Our ambition as educators is to support students in developing academic competencies and subject knowledge through facilitating conditions for deep and meaningful learning; through individual and collaborative enquiry; and through creating processes which build on students’ curiosity and creativity (see Alvarado and Herr, 2003; Hardie, 2015; Chatterjee et al., 2016).

In this chapter, we share our experience of designing and facilitating a pedagogical approach built around artefacts from our institutions’ special collections, with a view to promote active learning through exploration of objects and images. We are drawing on our reflections from a series of workshops: staff development events at University of Bedfordshire (UoB), and two national conferences; Playful Learning (Playful Learning, 2018), and the Active Learning Conference 2017 at Anglia Ruskin University (2018), which featured colleagues and students in our respective institutions (i.e. Foundation Level Business Studies; Final year undergraduate Education Studies; and Academic Writing for Postgraduate Music Education students). Here we share our practice in relation to the pedagogical method, Layers of Interaction, which underpins our design, and insights that transpired while facilitating these sessions and observing the dialogue between the participants and the artefacts.

Exploration through practice was our core aim: we wished to offer learners an alternative method of engaging with the discipline-related topic, including the underpinning academic skills, whereby the innovative element resided in introducing additional Layers of Interaction. In other words, we wished to introduce interactions with historic artefacts to facilitate activities, which would often be taught through the use of less complex methods, such as group or pair discussions. In so doing, we followed the core principles of the action research approach, to inform the steps of our exploration (cf. Somekh, 2006; McNiff, 2013). We then used participant feedback and our observations to inform our next steps, both in terms of feasibility of the method and further developments and adaptations.

Literature Review

There has been a growing recognition of the potential of special collections as catalysts, or ‘conductors’, of active learning in HE, stimulating both the sense of curiosity and playfulness, and responding to the expectations and demands of the specific discipline. Chatterjee et al. (2016) provide a detailed and convincing discussion on ways in which ‘multisensory’ interaction with objects facilitates active enquiry and meaning making in the classroom. Similarly, Hardie’s (2015) exploration of object-based learning offers activities that meet key learning outcomes and are engaging and entertaining at the same time. Both Chatterjee et al. and Hardie’s work are situated in a HE learning context and underpinned by museum education practice and literature, with discovery learning at its heart (see Bevan and Xanthoudaki, 2008; German and Harris, 2017). In our work, we draw on the idea that interaction with ‘unfamiliar’ objects can ‘surprise, intrigue and absorb learners’ and create rich learning (Hardie, 2015: 4), going beyond traditional ‘information-bearing materials’ in stimulating ideas and creative thinking (Chatterjee et al., 2016).

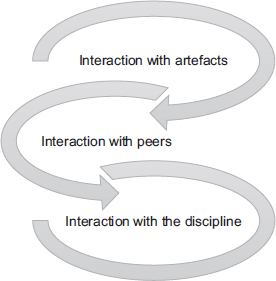

While exploration of, and interaction with artefacts from special collections is central to our pedagogical approach, we would like to draw attention to other interactions, which occur in parallel with learning through artefacts. Therefore, it may be useful to frame our pedagogical approach using three interaction ‘lenses’ namely:

- Interaction with the subject (enquiry-based learning)

- Interaction with artefacts (object-based learning)

- Interaction with peers (collaborative learning)

In Figure 11.1 we illustrate how these layers of interaction manifest themselves during a teaching and learning activity. Firstly, interrogating the objects (individually), then, continuing the dialogue with the artefacts as a group (collaboratively), and finally, connecting back to the discipline, or the discipline-specific outcome (knowledge, understanding, skill). The image illustrates how the interactions interlace during the teaching and learning activity, supporting and ‘fuelling’ one another. In fact, we argue that it is the interaction with the discipline that is being facilitated through the interaction with artefacts and with peers. This is an important distinction from the design point of view, as the method, and the activity will appear different to an activity participant or to an external observer, as opposed to how it will look to the facilitator. The next section explores each layer in more detail.

Figure 11.1Pedagogical method presented as layers of interaction

Interaction with objects

Object-based learning offers great potential for promoting individual enquiry, reflection, and knowledge construction; the latter is informed by prior learning experience. This approach echoes Piaget’s work (1976) on the interaction between subjects and objects. The subject enters into a dialogue with the object, and questioning and curiosity is encouraged and facilitated by the educator. The physicality and ‘multidimensionality’ of the objects and images play an important role too, as they invite curiosity, which is aided through haptic, visual and multisensory learning during the exploration process. Curiosity is particularly relevant to our work with special collection artefacts, and recent literature in the field of museum education has emphasised the potential for historical artefacts to act as an ‘agile’ tool (German and Harris, 2017), igniting creativity and enquiry in the classroom through the ‘unfamiliar’ (to students) knowledge they embody. Chatterjee et al. (2016) connect these features to Csikszentmihalyi’s (1988) concept of flow, whereby simultaneous engagement of cognitive, affective and psychomotor domains results in a state of immersion, which leads to higher cognitive processing and deeper learning. Falk and Dierking (2000) echo this discussion in their work on museum education and meaning making.

Interaction with peers

Individual interaction with the artefact, and the resulting reflection is subsequently followed by a series of peer interactions in small groups. We draw on Vygotsky’s (1978) socio-constructivist view of learning through interaction with others, whereby students develop their own understanding through collaborative activity with their peers.

We also expand the use of questioning in the style of Socratic dialogue (Paul and Elder, 2008), this time, in a social, collaborative context, with questions acting as drivers for developing critical thinking, reasoning, and own positionality, through verbal articulation (Vygotsky, 1978). In fact, literature on object-based learning suggests that interaction with objects frequently implies collaborative, socially situated activity. Brookfield (2012) advocates for group discussion as a social learning process, which creates space for exchange of critique, and therefore accommodates subjectivity (initial assumptions), and critical analysis (considering other views and incorporating them into own position). Further ‘deconstruction’ of the process of developing criticality can reveal such (emotional) dispositions as inquisitiveness and truth-seeking (see Facione et al. (1995); Giancarlo and Facione (2001), which links intellectual curiosity and criticality, echoing the discourse around object-based learning.

While the process of active learning is very much student-driven and student-centred (Chatterjee et al., 2016), the role of the facilitator is crucial for effective directing and managing of the dialogical process to support students in their interaction, by broadening and deepening the dialogue, encouraging reflection, reiteration, and the critical enquiry into the subject.

Interaction with the discipline

It may not be immediately obvious to participants that they are, in fact, interacting with the topic related to their discipline of choice, when they enter an explorative dialogue with artefacts and each other. Indeed, the main aim, and therefore, the overarching interaction occurs at the level of participants’ process of enquiry into an area of their field. In particular, the concept of open, ‘true inquiry’ (Banchi and Bell, 2008) is fitting here, whereby students are able to structure their own engagement (through questions) with the topic and formulate the results. Brown’s (2003) reference to enquiry-based learning as ‘inquisitive learning’, as opposed to ‘acquisitive learning’, is helpful here, as it draws parallels with curiosity and student-led process of construction of subject knowledge. Interaction with artefacts through peer collaboration is the pedagogical method that takes the participants beyond the immediate expectation of the teaching and learning approaches associated with the discipline. Scaffolded facilitation from one object to multiple, from direct to more open questions, welcoming complexity and multiplicity of opinions, and skilled questioning may help students ‘travel’ and cross the boundary between their preconceptions of the teaching method associated with their discipline of choice, and the method we present here. Dalrymple and Miller (2006) point to the importance of the pre-set learner identities, which can act as a ‘stumbling block’ for students who are invited to cross (expected) disciplinary boundaries to explore a previously unfamiliar and unexpected learning method. That said, by going beyond the (expected) discipline-specific approach, students arrive at a more meaningful, personalised and contextualised subject knowledge through the process of enquiry and discovery (see Bruner, 2009).

Designing the pedagogical approach

As mentioned earlier, our aim was to explore innovative teaching approaches which would provide students with an alternative way of connecting with subject-related material. It was important to create a learning environment that invites participants’ subjectivities and lived experiences, and builds on the latter, helping them navigate the process of enquiry, thus leading to a deeper, meaningful learning experience. We were also keen to use an approach that had potential to ignite participants’ sense of exploration and curiosity, and reinforce the enjoyable nature of critical and creative thinking.

It would also be fair to say that we share a ‘learning development’ approach, whereby an explicit importance is placed on the way students learn, as well as on the way students reflect on their own learning and knowledge construction. In other words, it was also our aim to bring students’ application of their academic competencies (i.e. criticality, creativity, information literacy), as well as their reflection on this process to the forefront of the learning process; to give shape to something that can be perceived as too abstract, and therefore may be difficult to grasp and apply. As authors and learning developers, we also come from different disciplines and backgrounds; this allowed us to develop three ‘strands’ of student learning: information and research literacy; narrative construction and research skills; and criticality in postgraduate academic writing.

The practice discussed here represents an amalgamation of developments that took place at a number of development and teaching events over an eighteen month period. The inspiration for our engagement comes from exposure to the object-based learning methodology, and its unique potential to invigorate the learning experience. Links to museum education and its underpinnings served as another foundation block for our exploration. The sentiment around universities’ special collections being underutilised resonated with us and presented an opportunity to both enrich our students’ learning and raise the profile of special collections and their value – not just historical, but also pedagogical.

As this is a practice-driven and practice-based exploration, elements and principles of action research were particularly useful to us, in terms of informing our approach and mapping out the steps. We naturally fall into the educator-researcher role, which would allow us to observe potential areas for experimental teaching and learning design, carry out the activity, make changes and inform further professional and learning development (cf. Somekh, 2006; McNiff, 2013). Of course, alongside the valuable position and the insights that the role of educator-researcher bring, it was paramount that we are aware of, and account for potential vulnerabilities such as awareness of own position, and how this subjectivity may be affecting the course of the exploration, as well as students’ subjectivities and input.

Conversations with archivists and librarians curating special collections in our respective institutions (Bhimani, 2018; UoB, 2018) ensured that a shared understanding was developed around the use of special collections as an aspect of active learning methodology. This iterative dialogical process involved different areas of expertise, in this case, museum education/historical canon and academic writing, information literacy and research skills; with the involvement of subject specialists at key points (i.e. Education Studies; Music Education; Business Studies).

Before the method was adapted for student learning, however, several staff development workshops were delivered, aimed at our teaching and academic support peers. In these events, each involving 10–15 participants, the methodological ‘formula’, grounded in object-based learning was offered to participants, whereby they went through the process of interaction with the artefacts and each other, approaching the activity through the lens of their own field of expertise. These development sessions served as a pilot and helped shape the method and the activity, and to consider possible adaptations and raise interest in the method as well as the special collections.

Participants in the staff development sessions were asked to explore artefacts from the UoB Physical Education archive and subsequently consider how similar activities could be used in their practice. Sufficient time was given to discussion around theoretical frameworks underpinning the activity (e.g. active leaning; object-based learning; discovery learning, enquiry learning), to ensure that the conceptual pedagogic understanding was developed, alongside the skill of facilitating and adapting the method for specific subject areas and topics.

In terms of design, each session followed a specific set of development steps: collaboration with our institution’s special collections colleagues to identify relevant and suitable collections and co-design activities; collating and grouping of artefacts relevant to the students; development of scaffolded explorative activities to support interaction with the objects and peers.

We worked on developing this activity with several groups of students that ranged in level and subject, across two institutions. The number of students ranged from 15–30 per session, allowing us to explore the approach in a range of contexts and group size. At the University of Bedfordshire, for example, we worked with students at Foundation and Undergraduate level. The three groups of Foundation Year Business students (ages between 16 and 18, 30 in each group) used the method as a way to engage with academic literature, through interrogation and questioning of a range of academic material. At the same institution, we also offered this approach to two groups of final year Education Studies students (30 students per group). These students were starting their dissertation project and used the method to practice formulating a research question and building a critical narrative.

At the Institute of Education, the method was used to explore criticality in the literature review process with Postgraduate Music Education students (20 students in 2017; 25 in 2018).

Facilitation of the approach

Participants were invited to interact with artefacts from our institution’s special collections (Bhimani, 2018; UoB, 2018): images, texts, historical records, physical objects. Sessions were staged to incorporate and build each of the three layers of interaction: interaction with objects, interaction with peers, and interaction with the discipline. Initially, one or two objects were explored and interrogated by participants, through consideration of a number of questioning prompts, and the subsequent objects were revealed to stimulate further questioning and exploration, both individually and in small groups. This culminated in an activity where students were asked to draw conclusions about the origin of the artefacts and interpret links between artefacts and what they represented.

The staging of the sessions and ‘layering’ of interaction were underpinned by the principles of ‘Socratic questioning’ (Paul and Elder, 2008) and the ‘think-pair-share’ format (Millis et al., 1995), a practice that promotes reflection and higher-order thinking through both individual reflection and group interaction. The use of Socratic questioning encouraged students to ‘dig beneath the surface of ideas’ (Paul and Elder, 2008: 36) and students in turn used Socratic questioning and dialogue to establish an ‘additional level of thinking’ and ‘powerful inner voice of reasoning’ (Paul and Elder, 2008: 36). In this way, critical thinking and reflection were embedded in the learning process and developed through the three layers of interaction.

Pedagogic practice informed by museum education and object-based learning offers students an opportunity to practice creative and critical enquiry and participant-led exploration into the subject matter. As Hardie (2015) suggests, teaching built around object-based enquiry can achieve the educator’s ultimate ambition: make the learning engaging and fun, while ‘hitting’ the learning outcomes. Using special collections not only gave us an extra dimension of engagement and tapped into the ‘curiosity’ domain of discovery-based learning, but also added value by broadening the learning experience and opening a ‘window’ into previously unexplored aspects of the university, and the related context and history. As facilitators and workshop ‘designers’, our task was to invite students to digress from direct interaction with the discipline by taking a detour to fully engage with the objects, individually and in groups, to develop and share subjectivities, and to notice commonalities and differences. Lastly, and very importantly, our task was to lead students through the process of ‘skill transfer’ (Gibbs, 2014) whereby the process of object-based learning enquiry would be deconstructed and applied to the enquiry into the discipline. Hence, the ‘sweet spot’ is where the critical and creative aspect of the dialogue with an artefact can be noticed and made more tangible through articulation; this newly visible creative and critical thinking can then be used to broaden and deepen interaction with the subject knowledge.

Findings

As outlined above, we aimed to use participant feedback on how they found the method, to be able to develop our thinking and practice further. Although the development and testing of the method was framed from the outset as an exploration into pedagogical practice, we used core principles of action research, such as initial reflection on an existing issue, constructing a response or action, collecting evidence via feedback and observation, and introducing further re-iterations following post-event reflection (McNiff, 2013). Thus, we used participant discussions and feedback, and our own observations to inform our reflection, as well as the next steps in method development.

While keen to capture participants’ views on the use of the pedagogical method, it was equally important to strike a balance between encouraging feedback and not contributing further to what could be described as ‘survey fatigue’. Using ‘post-it note pedagogy’ (Quigley, 2012) to collect students’ views and generate discussions served as a simple and effective solution (Peterson and Barron, 2007).

Feedback from the sessions echoed our reflections and helped us draw conclusions about the participants’ engagement, motivation and interaction with this learning method, providing us with a direction for further development. Considering the innovative nature of the method, and the potential challenge of engaging with something unexpected, the choice was made to capture a relatively surface ‘layer’ of students’ perceptions through post-its. Therefore, we asked our students to respond to three questions: (a) ‘What did you enjoy the most?’ (b) ‘What did you enjoy the least?’, and (c) ‘what did you find most surprising/unexpected?’ While the first two questions would help us ascertain the key aspects of the method, as well as the direction for future improvement, the third question was grounded in the ‘curiosity’ and the ‘discovery’ learning aspect of the methodology. We were also equally keen on getting a quick view of ‘what worked’ and what could be done better/differently, as learners were engaging with not only a new, but unexpected approach to learning and to the discipline.

Overall, student feedback was consistent with reflections and verbal feedback from staff development events and conference workshops; key themes in feedback from all participants were also supported by our observations.

Interaction with objects

The majority of the feedback from participants across all subjects and levels of study indicated that they enjoyed handling, investigating and exploring the objects and their history. When reflecting on what we observed, all three facilitators also agreed that the excitement in the room increased when engaging and interacting with the objects, creating an engaging learning environment. The positive feedback on working with the artefacts supports the idea that learning through interaction with objects promotes effective learning, plus development of knowledge and skills that go beyond the immediate subject (see Falk and Dierking, 2000; Piaget, 2007; Gibbs, 2014; Hardie, 2015; Chatterjee et al., 2016; Maybee et al., 2016).

Observations of group dynamics reinforced the idea that facilitation of meaningful transfer of learning requires skilful facilitation and contextualisation for level of study, discipline, group size, and composition. For example, staff members and postgraduates responded quickly in deconstructing the core principles of the activity, which could then be applied to other contexts (e.g. the process of creative exploration, critical thinking and evaluation, synthesis); they recognised the skill of transfer as one of the aims of our methodology design. In comparison, the Foundation cohort needed more time and scaled instruction to establish the connections between the process of object-based learning and application of the related skills and processes to the discipline-related task that followed. The Foundation groups were also larger in size than others, which affected facilitation and pace of the session.

Students at the higher level of study and, even more so, teaching staff would be more familiar with the language and expectations of HE learning, both in terms of discipline-specific knowledge and associated learning approaches and competences. Therefore, the facilitation for earlier levels of study, in our case, Foundation, would ideally include a more gradual scaffolded instruction, possibly through a series of sessions, which would allow more time for setting the context and building familiarity with a breadth of learning approaches to their discipline of choice. The Foundation students did enjoy working with the ‘unusual’ and ‘old’ artefacts as much as other groups, stating that the opportunity to physically handle the objects and learn something about them was a pleasantly surprising element of the activity. This view is supported by the feedback from other groups, where participants found the objects and the associated history and meaning surprising and unexpected (Hardie, 2015; Chatterjee et al., 2016), and participants reiterated this in response to the question ‘what did you enjoy the most?’ For facilitators, this means that once the sense of engagement and level of familiarity is established, facilitation can move towards capturing the understanding of the knowledge and processes encompassed in the activity, and how they can be transferred to the interaction with the discipline.

Participants’ enjoyment of the object-based learning aspect of the activity also meant that the most common answer to the question ‘what did you enjoy the least?’ was ‘not enough time’. Despite sessions varying from one to two hours, it was clear that every section of the activity could have been allocated more time, whether exploring the objects, engaging in the discussion, and deconstructing and applying the skills and processes utilised during the interactions. This would need to be taken into consideration in methodology design and facilitation. Factors that play an important role are familiarity with processes and practices in HE, group size, and the subject-related task that requires transfer of skills, competencies and processes practised through object-based learning.

Interaction with peers

Written and verbal feedback suggest that collaboration was not only perceived as enjoyable, but also as a method that helped explore the objects in more depth, and thus helped generate ‘interesting ideas’. Both students and staff expressed the view that ‘sharing the questions with others’, and ‘sharing analytical experiences’, helped them stay engaged with the activity and ‘think outside the box’; the latter suggests the appreciation of, and perhaps slight surprise at, own creativity. Some participants made similar comments in response to the question ‘what did you find most surprising/ unexpected?’ Our observations matched participant comments; the objects created lively discussions and held participants’ attention. Participants were keen to share their views with others and were interested to hear alternative interpretations and commentary from others. These messages echo the literature on interaction with others (Vygotsky, 1978) and group discussion as a means for facilitating energetic, engaging and meaningful learning (Brookfield, 2012).

We would like to emphasise the fact that capturing different ways of thinking, and therefore, learning, was central to our method; this is something that would come through most clearly in the interaction with peers. The activity design aimed to highlight and make more tangible how we observe and interpret differently depending on background and perspective, which was confirmed in the student feedback. In the staff development sessions, participants demonstrated high levels of autonomy; they were constantly reflecting and considering when and where they could adapt and utilise the activities in their own teaching. Their feedback was similar to reflections of the postgraduate group: both could see the value in the techniques for their own practice and skill development. In comparison, the Foundation group found more structure, guidance and reassurance helpful to ‘stay’ with the process of exploration and go deeper into their own observation and reflection. Some of their feedback was more descriptive and brief than that of higher level participants. Reasons for this may reflect the expectations imposed by the discipline (i.e. Business Studies rather than Education), as well as the level of study (i.e. Foundation rather than final year, and postgraduate). This observation creates an opportunity for a deeper exploration into how this method aligns with different disciplines.

Interaction with the discipline

As mentioned earlier, it is the interaction with the discipline and the discipline-related skills which constitutes our ultimate aim, which we arrive at through two additional layers of interactions. Subsequently, this process facilitates the transfer of relevant skills, competencies and processes. Some participants saw the connection between ‘playing detective’ and ‘writing down questions about the photos’ and therefore engaging with principles of discovery and ‘inquiry-based learning’ (Brown, 2003), and helping them with ‘bouncing ideas’ and ‘breaking down’ the process of ‘analysing a lot of data or literature’. Reflection and the opportunity to understand the subject in greater detail, as simulated through the process of object-based learning, were also mentioned. Parallels can be drawn here with students’ self-contextualised learning (Bruner, 2009).

Again, responses differed between Foundation, final year, and Postgraduate students, and practitioners. The Foundation group attempted to synthesise the information from the objects but seemed to find it more difficult to transfer those skills and processes in analysing literature. The final year and postgraduate groups were more adept at synthesising the objects and could express their own subjectivities, as well as explore different perspectives respectfully. They seemed to have fully understood the benefit of being curious when researching objects, one response even stated that they enjoyed being a ‘detective’ with objects about their subject that they never knew existed. We varied our questioning facilitation accordingly, to support the groups in their exploration. Following this thread, it is unsurprising that the professional participants were considering the approach and its transferable application, demonstrating high levels of autonomy and freedom.

Similarly, although with slightly less autonomy, Education Studies cohort feedback indicated that they valued the creative, interesting and unexpected nature of the session. They viewed the session as an opportunity to both reflect on their own perspectives and visual literacy skills, and to think creatively about connections between objects. They also enjoyed thinking creatively about the session process and how they could adapt and amend the session to support their own practice – something that we hoped would happen.

The Foundation Business Studies students liked that the session gave them the opportunity to question as well as learn new analytical skills. They required more scaffolded facilitation to see the wider uses of the skills they were utilising; that said, participants eagerly immersed themselves in the interaction with the objects. They embraced the opportunity to be creative in their interpretations of possible connections between images.

The MA Music Education group expressed appreciation of the fact that the session allowed them to be reflective and practise their criticality, making connections in new and innovative ways, and structuring the process of their enquiry. They responded well to our invitation to exercise creative expression and freedom of interpretation beyond what they would normally be used to. Parallels can be drawn here with Banchi and Bell’s (2008) ‘true inquiry’, where students scaffold their own engagement with the topic.

Conclusion

The pedagogical approach presented here facilitates creative engagement with the discipline through a layer of interactions, grounded in object-based learning, collaboration, discovery and enquiry learning. As our practice and participant feedback demonstrates, exploring physical artefacts from special collections at the level of both individual and group activity provides participants with opportunities to identify approaches, processes and skills that are necessary for acquiring discipline-related knowledge and understanding. Such important and often abstract concepts such as critical thinking and analysis, creativity and exploration, and synthesis, can become more tangible as processes and competencies. This deconstruction and reconstruction of the process of interaction with the objects, and then the application of the reconstructed process, requires participants to develop what Gibbs (2014) describes as ‘skill of transfer’.

Feedback and observations suggest that groups of different levels of study may require a varied amount of support and facilitation. In particular, it was clear that this method is most effective when sufficient time is allocated for exploration of the artefacts, discussion and linking back to the discipline and learning outcomes. Peer interaction and skilful dialogic facilitation from practitioners also play a vital role in how effective the process and the outcome are.

References

Alvarado, A.E. and Herr, P.R. (2003) Inquiry-Based Learning Using Everyday Objects Hands-On Instructional Strategies That Promote Active Learning in Grades 3–8. London: SAGE.

Anglia Ruskin University (2018) Active Learning Conference 2017. Online. www.anglia.ac.uk/anglia-learning-and-teaching/cpd-opportunities/events/active-learning-conference-2017 (accessed 7 March 2019).

Banchi, H. and Bell, R (2008) ‘The many levels of inquiry’. Science and Children, 46 (2), 26–9.

Bevan, B. and Xanthoudaki, M. (2008) ‘Professional Development for Museum Educators: Unpinning the Underpinnings’. The Journal of Museum Education, 33, 107–19.

Bhimani, N. (2018) UCL Institute of Education Special Collections: Rainbow. Online. https://libguides.ioe.ac.uk/specialcollections/rainbow (accessed 12 December 2018).

Brookfield, S. (2012) Teaching for Critical Thinking: Tools and Techniques to Help Students Question Their Assumptions. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Brown, P. (2003) ‘The Opportunity Trap: education and employment in a global economy’. European Educational Research Journal, 2 (1), 141–79.

Bruner, J.S. (2009) The Process of Education. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

Chatterjee, H., Hannan, L. and Thomson, L. (2016) ‘An introduction to Object-Based Learning and Multisensory Engagement’, in H. Chatterjee and L. Hannan (eds), Engaging the Senses: Object-Based Learning in Higher Education. London: Routledge, 1–18.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1988) ‘The Flow Experience and its Significance for Human Psychology’, in M. Csikszentmihalyi and I.S. Csikszentmihalyi (eds), Optimal Experience: Psychological studies of flow in consciousness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 15–35.

Dalrymple, J. and Miller, W. (2006) ‘Interdisciplinarity: a key for real-world learning’. Planet, 17 (1), 29–31.

Facione, P., Giancarlo, C, Facione, N., and Gainen, J. (1995) ‘The disposition toward critical thinking’. Journal of General Education, 44 (1), 1–25.

Falk, J. and Dierking, L. (2000) Learning from museums. London: Rowman and Littlefield.

German, S. and Harris, J. (2017) ‘Agile Objects’. Journal of Museum Education, 42 (3), 248–57.

Giancarlo, C, and Facione, P. (2001) ‘A look across four years at the disposition toward critical thinking among undergraduate students’. Journal of General Education, 50 (1), 29–55.

Gibbs, G. (2014) 53 Powerful Ideas all Teachers should know About: Transferable skills rarely transfer (Idea Number 3, May 2014). Online: https://www.seda.ac.uk/resources/files/publications_147_3%20Transferable%20skills%20rarely%20transfer.pdf (accessed 17 December 2018).

Hardie, K. (2015) Innovative pedagogies series: Wow: The power of objects in object-based learning and teaching. Online. https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/system/files/kirsten_hardie_final.pdf (accessed 17 December 2018).

Kukhareva M., Lawrence, A. and Koulle, K. (2018) ‘Creative pedagogies: using objects and images to promote active learning Workshop – supporting material’. Paper presented at Active Learning Conference 2017, 12 September 2017. Online.

https://www.anglia.ac.uk/-/media/Files/Anglia-learning-and-teaching/Active-learning-conference/Creative-pedagogies—Kukhareva,-Lawrence-and-Koulle—supporting-resource.docx?la=en&hash=4C4D30DDFEA6157A9F462A3B27CAA771 (accessed 22 March 2019).

Maybee, C, Doan, T. and Flierl, M. (2016) ‘Information Literacy in the Active Learning Classroom’. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 42(6), 705–11.

McNiff, J. (2013) Action Research. 3rd Edition, London: Routledge.

Millis, B., Lyman Jr., F.T. and Davidson, N. (1995) ‘Cooperative structures for higher education classrooms’, in H.C. Foyle (ed) Interactive Learning in the Higher Education Classroom. Washington, DC: National Education Association, 204–23.

Paul, R. and Elder, L. (2008) ‘Critical Thinking: The Art of Socratic Questioning, Part III’. Journal of Developmental Education, 31 (3), 34–5.

Peterson, E., and Barron, K.A. (2007). ‘How to Get Focus Groups Talking: New Ideas That Will Stick’. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 6 (3), 140–4.

Piaget, J. (1976) The Grasp of Consciousness: Action and Concept in the Young Child. Cambridge: Harvard University Press

Piaget, J. (1926; 2007) The Child’s Conception of the World. Washington, DC: Rowman and Littlefield.

Playful Learning (2018) Playful Learning Programme 2017. Online. http://conference.playthinklearn.net/blog/programme17 (accessed 7 March 2019).

Quigley, A. (2012) Post-it note pedagogy. The confident teacher. Online. www.theconfidentteacher.com/2012/12/post-it-note-pedagogy-top-ten-tips-for-teaching-learning/ (accessed 8 December 2018).

Somekh, B. (2006) Action Research: a methodology for change and development. Maidenhead: Oxford University Press.

University of Bedfordshire (2018) Bedford Physical Education Archive. Online. https://lrweb.beds.ac.uk/libraryservices/using-the-library/archive/special-collections/bedford-pea (accessed 12 December 2018).

Vygotsky, L. (1978) Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.