Case Study #3: The Political Ecology of the Garden (Education & Social Work)

In the northern part of Sussex campus, on the edge of the Downs, is the Sussex Forest Food Garden. There is a second-year elective module associated with the garden, rooted in a civic ecology model. Students design an aspect of the garden, which they then hand over to the next year’s cohort to plant. The module emphasises working with the land and communities – within and beyond the university – and fostering resilience through interrelationships between the natural world and collective human action. It makes space for student agency to respond to human-induced climate change and biodiversity loss, and embraces the uncertainty inherent in such a complex, contingent and indeterminate endeavour.

In Week 3, students are taught about interpreting the politics of landscapes, especially gardens. We use a chapter in Rebecca Solnit’s Orwell’s Roses (2021). As Solnit writes: “A garden is an ideal version of nature filtered through a particular culture […] A garden is what you want (and can manage and afford), and what you want is who you are, and who you are is always a political and cultural question. It’s true even of vegetable gardens – of whether you plant cabbages or chillies – though more so with pleasure gardens” (Solnit 2021). There is a lecture and a workshop.

#LECTURE. 1a. Landscape as language. A poem can be about a garden. Can a garden be about a poem? Anne Whiston Spirn writes in The Language of Landscape that landscape “contains the equivalent of words and parts of speech – patterns of shape, structure, material, formation, and function. All landscapes are combinations of these. Like the meanings of words, the meanings of landscape elements (water for example) are only potential until context shapes them. Rules of grammar govern and guide how landscapes are formed, some specific to places and their local dialects, other universal. Landscape is pragmatic, poetic, rhetorical, polemical. Landscape is scene of life, cultivated construction, carrier of meaning. It is a language” (Spirn 1998, 15).

1b. Landscape intertextuality. By exploring poetry, song, paintings, and other culture about landscapes, we can open up the landscapes themselves as forms of culture. And like other forms of culture, landscapes have embedded politics we can attempt to locate and debate. Solnit writes that “nature is political. So are gardens. Flowers. Trees. Water. Air. Soil. Weather.” (p.154). As the poet and “avant-gardener” Ian Hamilton Finlay writes, ‘Certain gardens are described as retreats when they are really attacks’ (cited in Solnit, p. 150). Finlay’s own installation-garden, Little Sparta, is intricately expressive, filled with hundreds of artworks including sculptural concrete poetry.

1c. Contextualising garden features historically. But Finlay’s Little Sparta may feel like an extreme case — a garden that practically sings its stories. How can we learn to decipher the other gardens, the ones that only whisper and murmur? Here we benefit from historicising. At first, a garden may feel like it’s just a mix of the unavoidable and the arbitrary. Things are the way they are because (a) that’s how they work best, or (b) because somebody happened to like them that way (or just didn’t care). Exploring the histories behind a few features can transform the garden as a whole, allowing meaning and potential meaning to pervade it through and through.

We focus especially on the C18th English garden. As the century began, stiff neoclassical formalism was going out of fashion among the landed elite. Nature was no longer seen as an unruly realm in need of taming. Instead, the work of landscape designers like William Kent and Capability Brown was praised for subtlety and sensitivity to nature’s existing beauties.

The ha-ha — a fence concealed in a ditch, creating a boundary, while preserving the illusion that the estate is continuous with the surrounding countryside — is a very neat illustration. More broadly, as Solnit writes: “The same kind of laborious earthmoving and outdoor plumbing as at Versailles might be employed, but to make serpentine streams and rolling terrain that hid the handiwork behind it. Nature was supreme except that English taste and money were her master.”

Such gardens did enact an aesthetic revolution, eventually feeding into the rustic spinneys and ruined hermitages of Romantic garden landscapes. But Solnit describes how these gardens also made a deeply conservative argument, that “English aristocracy and the social hierarchy were themselves natural, that the aristocrats’ power and privilege was rooted in the actual landscape, even as the humbler dwellers in the landscape were uprooted in the enclosure acts and driven to industrial labor in cities or to emigration.”

1d. Enclosures of the commons began in the Middle Ages. Raymond Williams writes: “Poets have often lent their tongues to princes, who are in a position to pay or to reply. What has been lent to shepherds, and at what rates of interest, is much more in question […] Sidney’s Arcadia [1593], which gives a continuing title to English neo-pastoral, was written in a park which had been made by enclosing a whole village and evicting the tenants” (Williams 1973). Between 1725 and 1825, as English landowners began to frame themselves as unobtrusive stewards of nature’s wisdom and beauty, they also appropriated around 6 million acres of common land. Uprooted, impoverished rural working class were driven to the industrialising cities.

Commons historian Peter Linebaugh describes a trinity of brutally transformative forces at the time: enclosure, slavery, mechanization. As Solnit writes, “There might be virtuous ways to love nature, but the love of nature is no guarantee of virtue” (156). She cites English Heritage (2013): “Both the merchants and the members of the British landed elite who were involved in the proliferation of country houses in the late 17th century (the latter to consolidate their status and the former to gain entry into that elite) increasingly utilised notions of gentility, sensibility and cultural refinement in part to distance themselves from their actual connections to the Atlantic slave economy” (in Solnit 2021, 163).

1e. We finish by jumping forward and exploring George Orwell’s relationship with gardening. “The source of his self-regenerative power lay in his joy in the ordinary, common experiences of day-to-day existence and particularly of contact with nature” (George Woodcock, Orwell’s friend, cited in Solnit, 46).

#WORKSHOP. Writing the Sussex Forest Food Garden. If landscapes can be interpreted, then they can also be written. “Landscape architects, gardeners and architects have been ‘writing’ landscape stories since the early days of civilization” (Alon-Mozes, 2012, 31). This session aims to support and inspire students to decide what they want to do, and what they want to say, with the Sussex Forest Food Garden. It is in three parts:

- 2a. Identify the political & cultural in landscape stories

- 2b. Identify potential themes for the Forest Food Garden landscape story

- 2c. Consider uncertainty in garden designs (both in the terms of metaphor and natality)

2a. In small groups, students discuss the Spirn quotation from the lecture: “Landscape is scene of life, cultivated construction, carrier of meaning. It is a language.” (Spirn 1998, 15). They come up with examples of landscape as language, and feed these back to the whole group.

We use these as springboard into a discussion of metaphors. Plants provide us ‘with metaphors and meanings and images, with stems, offshoots, grafts, roots and branches, information trees, seeds of ideas, fruits of our labor, cross-pollinations, ripeness and greenness, and with the symbolic richness of the things we do to our domesticated plants: weeding and pruning, sowing and reaping, and so much more’ (Rebecca Solnit, 2021, p. 126). Students are invited to explore these, and suggest more of their own.

‘ll faut cultiver notre jardin’ (Voltaire). Within sustainability discourse, gardening metaphors are common. But by now it’s clear that gardening is not just one thing! Different gardens have different politics. So if we do accept a role as the planet’s gardeners, this raises as many questions as it answers, as Clark and Munn (1986) point out: “What kind of garden do we want? What kind of garden can we get? The first of the questions—’What kind of garden do we want?’—ultimately calls for an expression of values. The values on which we have based this study—the kinds of garden we want—are suggested in our choice of title: The Sustainable Development of the Biosphere. The common sense meaning of ‘sustainable’ is a good first approximation of our intended meaning. We seek to distinguish gardening strategies that can be sustained into the indefinite future from those that, however successful in the short run, are likely to leave our children bereft of nature’s support.”

2b. Experiment with designs inspired by literary texts.

In pairs, students are asked to spend about fifteen minutes doing the following:

- Read one of the three texts (Louise Glück’s ‘Nostos’, Danielle Legros Georges’s ‘Lingua Franca with Flora’ and Michael Rosen and Helen Oxenbury’s ‘We’re Going on a Bear Hunt’).

- Identify one or two themes to translate into a garden design.

- Sketch a rough garden design that incorporates these themes (focusing on the themes, not the literary texts).

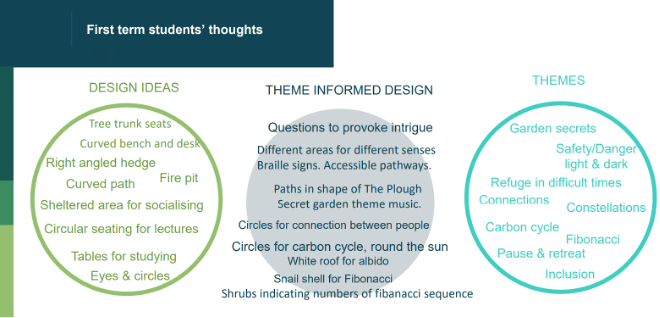

2c. Identify themes for the Forest Food Garden ‘landscape story’.

Again in pairs:

- Think of narratives / themes that you feel already exist or should be included in the landscape story of the FFG social areas and perennial shrub planting.

- Write each theme on a separate Post-it.

- When competed, place your Post-its on the wall.

- Then we all come together as a group to cluster, discuss, and agree on key themes.

Thoreau writes in Walden (1854): “Why concern ourselves so much about our beans for seed, and not be concerned at all about a new generation of men? We should really be fed and cheered if when we met a man we were sure to see that some of the qualities which I have named, which we all prize more than those other productions, but which are for the most part broadcast and floating in the air, had taken root and grown in him. Here comes such a subtle and ineffable quality, for instance, as truth or justice, though the slightest amount or new variety of it, along the road. Our ambassadors should be instructed to send home such seeds as these, and Congress help to distribute them over all the land.”

Conclude the session by bringing these themes together with the theme of uncertainty. How do we design for and with uncertainty?

“Emancipation is also knowing that one cannot place one’s thinking into other people’s heads, that one cannot anticipate its effect. I’ve said what I have to say, and people will make of it what they will . . . I never say what should be done or how to do it. I try to redraw the map of the thinkable in order to bring out the impossibilities and prohibitions that are often lodged at the very heart of thought that imagines itself to be subversive” (Rancière, 2007, 269).

Perpetua Kirby