5 Planetary Boundaries & Doughnuts: Activity Seeds

-

Diverse economies

J.K. Gibson-Graham’s A Postcapitalist Politics (2006) and Handbook of Diverse Economies (2020) aim to construct a new language of economic diversity, by attending to the more-than-capitalist practices that already exist, and to their latent potentials. You could invite students to identify ways of coordinating action, allocating resources, etc., that exist outside markets and money (in the texts you’re teaching, or in their own experience). In what ways might these be part of extractivist capitalism nonetheless? How might they articulate alternatives? J.K. Gibson-Graham might be interestingly read with / against Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams’s Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work (2015), which is impatient with “[h]orizontalism, localism, nostalgia, resistance and withdrawal” (p. 48).

-

Safe operating spaces

Encourage students to think about how ‘safety’ — and related concepts such as risk, predictability, security, freedom — operate across various social, cultural, and historical contexts. “Security has become one of neoliberalism’s signature growth industries, exemplified by the international boom in gated communities, as walls have spread like kudzu” (Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, p. 20). “As the climate crisis has become increasingly difficult to ignore, many of the world’s most powerful state and corporate actors have shifted from a discourse of denial and scepticism to a discourse of securitization” (Thomas and Gosink, ‘At the Intersection of Eco-Crises, Eco-Anxiety, and Political Turbulence: A Primer on Twenty-First Century Ecofascism’). Choose a literary text or piece of media, and examine how it constructs (perhaps deconstructs) the boundaries between ‘safe’ and ‘unsafe.’ Here are a handful of critical texts that may say interesting things about safety (not all explicitly linked with sustainability):

- Beck, Ulrich. 1992. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. Theory, Culture & Society.

- Dupré, Denis, and Preston Perluss. ‘Mastering Risks: An Illusion: Truth and Tropes on Jeopardy’. Research in International Business and Finance 37 (1 May 2016): 620–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2015.12.001.

- Mythen, Gabe. 2021. ‘The Critical Theory of World Risk Society: A Retrospective Analysis’. Risk Analysis 41 (3): 533–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.13159.

- Collins, Patricia Hill. 2000. ‘The Power of Self-Definition’ in Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. New York: Routledge.

- anonymous refused. 2014. ‘For Your Safety and Security …’. Tumblr. 2014. anonymousrefused.tumblr.com/.

- Hanhardt, Christina B., Jasbir K. Puar, Neel Ahuja, Paul Amar, Aniruddha Dutta, Fatima El-Tayeb, Kwame Holmes, and Sherene Seikaly. 2020. ‘Beyond Trigger Warnings: Safety, Securitization, and Queer Left Critique’. Social Text 38 (4 (145)): 49–76. https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-8680438.

- Douglas, Mary. 1992. Risk and Blame: Essays in Cultural Theory. London ; New York: Routledge.

- Scoones, Ian, and Andy Stirling, eds. 2020. The Politics of Uncertainty: Challenges of Transformation. Pathways to Sustainability. Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY: Routledge.

- Wallace, Molly. 2016. Risk Criticism: Precautionary Reading in an Age of Environmental Uncertainty. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Levontin, Walton et al. 2022. Communicating Climate Risk: A Toolkit. AU4DM / COP26 Universities Network.

-

Data over time

The National Doughnuts dataset is an interactive tool that lets students compare data on planetary boundaries over time and across nations. (Unfortunately it only seems to go up to 2015). Here is a related article in The Conversation. There are also plenty of other tools and activities in the Doughnut Economics Action Lab database.

-

The Planetary Boundaries model: scope, use, and alternatives.

What are the benefits and drawbacks of the Planetary Boundaries model? What is this model for, and what is it not for? Challenge students to come up with alternative ways of formulating the same set of issues, e.g. focusing more on justice and intersectionality, and/or on theories of change.

-

Mapping our preconceptions

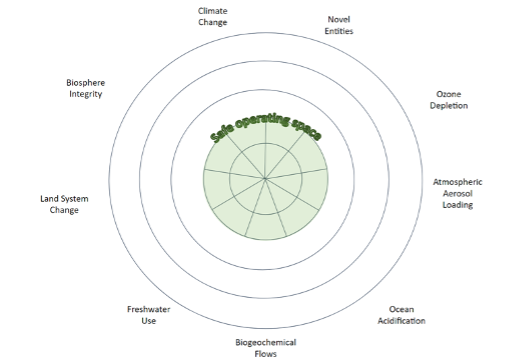

How are ideas about environmental degradation generated, circulated, transformed? Planetary boundaries are pretty important, so why isn’t there greater public awareness? Experiment with inviting students to share preconceptions (e.g. “Nine boundaries have been identified, what do you think they are?”) — reassuring them that ‘wrong’ answers are exactly what we’re interested in for this exercise! For example, a recent study compared students and scientists’ “conceptions on socioeconomic growth within planetary boundaries” in order to “develop instructional guidelines for teaching based on these findings” (Lampert, Niebert, and Wilhelm 2021). Students incorrectly identified population growth as the primary cause of environmental degradation. Students could fill out a blank diagram to estimate the relative seriousness of different issues:

6. Systems thinking

Explore emergence, tipping points and interventions by pointing to examples from the texts and media you’re teaching, and/or create exercises and games to illustrate these principles. Emergence, in a nutshell, is when a system exhibits behaviours, because of the interactions of its parts, which would be difficult or impossible to foresee just from examining the parts on their own. A tipping point is when a system crosses a critical threshold such that its behaviour rapidly reorganises. There are various online tools, like Loopy, that students could use to construct models of systems. Could you use it to create a model of a poem, a film, a novel? Why, why not? What happens when you try?Meadows, Sweeney and Martin-Mehers’s The Climate Change Playbook (2016) contains some teaching inspiration. One activity (‘Triangles’) has players walking around slowly, each player trying to establish themself equidistant between their two ‘reference point’ players — one chosen at random, one who is the same for the whole group. The activity can illustrate that unpredictable complex behaviour can arise from simple rules (how long will the system take to reach an equilibrium?), and also that not all interventions are equal — stopping the universal reference point has a much bigger impact than stopping any other player.

-

Historicise systems thinking

Students could also explore the history, politics, culture and aesthetics of these concepts In this toolkit, we generally like “systems thinking” — it is a flexible and empowering framework, which reminds us that we cannot rely on simplistic distinctions between society and nature, and it is a way for arts and humanities students to explore issues in model construction that doesn’t require heavy maths. Then again, systems thinking also has its own politically and ethically complex history. Systems theory and systems thinking emerges from an intellectual mix that includes Operations Research shaped by WWII and Cold War funding priorities (see e.g. RAND Corporation, The Cowles Foundation, Macy Foundation Conferences, American Society for Cybernetics, MIT Sloan System Dynamics). Its interest in feedback loops and emergence can be traced back through neoclassical economics and classic political economy, including Adam Smith’s invisible hand and self-interested butcher, brewer, and baker, and Bernard de Mandeville’s “Private Vices, Public Virtues”. Philosophy and literary and cultural theory also offer many resources for critiquing systems thinking. As West et al. point out, “sustainability researchers are increasingly drawing on scholarship from the ‘relational turn’ in the humanities and the social sciences to propose a paradigm shift for sustainability science: away from focusing on interactions between entities, towards emphasizing continually unfolding processes and relations” (West et al. 2020).

-

Interconnections

Students are randomly assigned dimensions of the doughnut to portray. They mingle with the other dimensions and discuss possible interconnections. See the DEAL database for a full activity description. Alternatively, get students to use an online tool to build their own models of trade-offs and complementarities.

-

Check out Earth Overshoot Day

– a simple concept that reminds us that we are living beyond our means. Ask students to read through the solutions suggested to #moveTheDate and discuss which they feel more and less empowered by: https://www.overshootday.org.

-

Browse the resource table for more ideas

E.g. Sustainability Exchange, DEAL.