15 Ecocentrism in Policy and Law

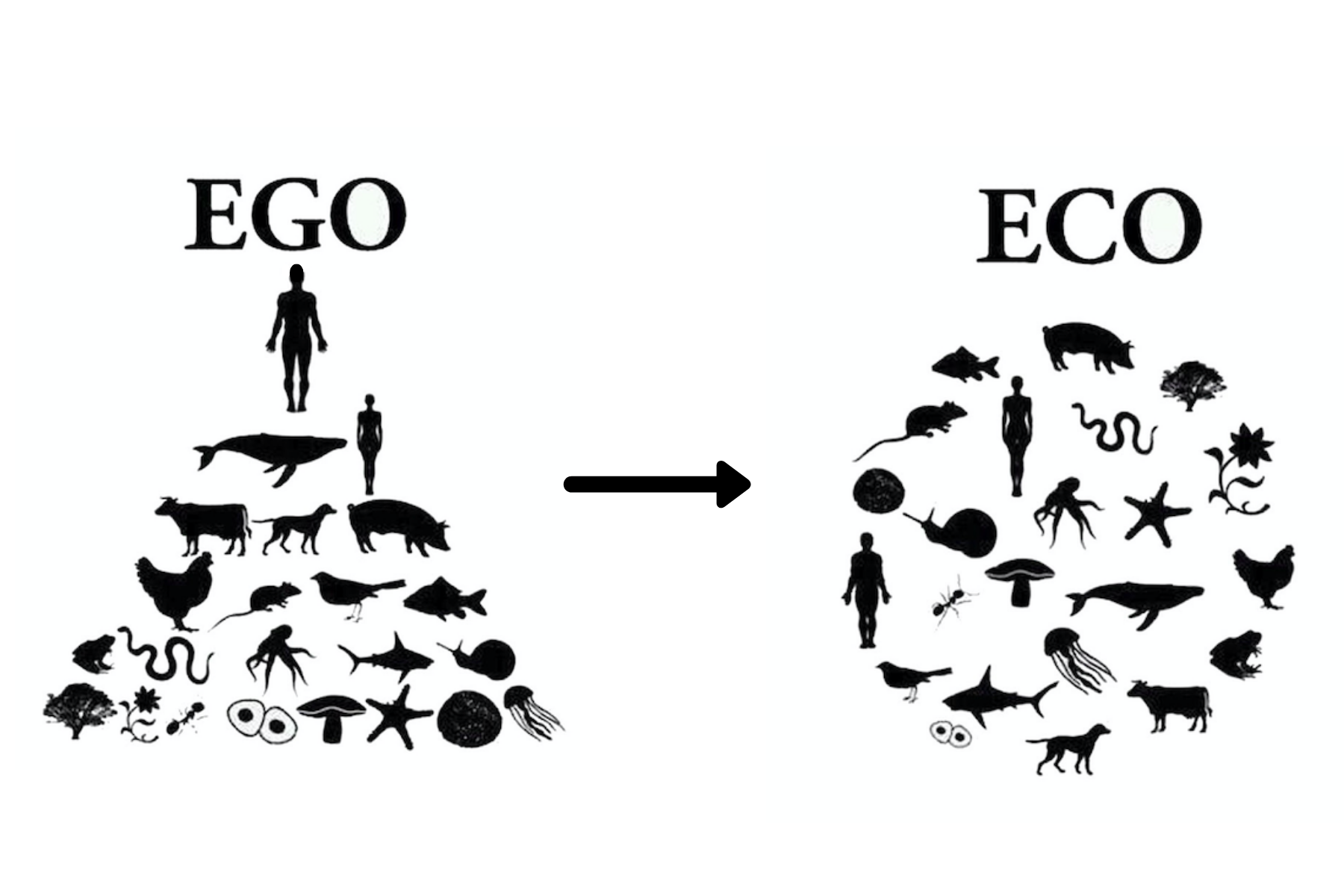

“This shift in perspective – from pyramid to web, from pinnacle to participant – also invites us to move beyond anthropocentric values and to recognise and respect the intrinsic value of the living world.”

— Kate Raworth

One obvious criticism of the SDGs is that they are still fundamentally centred on humans (and in fact, on one particular vision of human flourishing, based on economic growth). Even conservation agendas are largely driven by the concept of ecosystem services which place extrinsic value on natural processes in terms of what they can do for us as humans. Intuitively, we need to think beyond human needs and place intrinsic value on other life forms and natural processes. Various philosophical and legal shifts are underway that do just that.

-

What is anthropocentrism? What is ecocentrism?

Most environmental law is anthropocentric (human-centred). That doesn’t mean it ignores nature. Human wellbeing depends on nature, so laws which protect humans may also indirectly protect nature.

Most policymaking takes a similar approach. Natural capital provides many benefits to humans. Monetary values can be assigned to these services, which assists policymakers making complex decisions. These benefits are sometimes called ecosystem services.

However, this anthropocentric approach is at odds with many Indigenous perspectives, as well as the overlapping discourses of Earth Jurisprudence and Rights of Nature. These approaches emphasise the intrinsic moral value of natural entities, rather than their value to humans. Yes, bees pollinate our crops which sustain our economies. But those bees and those plants also matter in their own right.

Sussex Spotlight: ‘Harmony with Nature: towards a new deep legal pluralism’

In this article Helen Dancer (School of Law, Politics and Sociology, University of Sussex) explores the “histories, ontologies and discourses that have shaped two contrasting approaches to human-Earth relations in debates and legal frameworks for sustainable development. Anthropocentric discourses of nature as service-provider underpin the dominant approaches within ecology and economics. Ecocentric discourses of Nature as subject are reflected in Rights of Nature movements, particularly in the Americas, and at an international level, in the United Nations Harmony with Nature Programme.” Dancer argues “a deep legal pluralism that both decentres anthropocentric thinking on the environment and decentres the state in the development of Earth law. This places responsibility for the environment and the equitable sharing of power at the heart of legal frameworks on human-Earth relations and recognises the diversity of ontologies that shape these relationships in law and practice.”

Dancer, Helen. 2021. ‘Harmony with Nature: Towards a New Deep Legal Pluralism’. The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law, 53 (1): 21–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/07329113.2020.1845503

-

What are ecosystem services?

Ecosystem services is an anthropocentric approach to land management and policymaking. Ecosystem services can be divided into:

- Provisioning Services: Water, fish, livestock, vegetables, fruit, medicines, timber, wood fuel, fossil fuels, etc.

- Regulating Services: Carbon storage, water purification, decomposition, pollination, erosion control, etc.

- Cultural Services: Recreation, spirituality, knowledge, beauty, enriched experience and imagination, etc.

- Supporting Services: The services that underlie these services. Habitats for biodiversity, photosynthesis, nutrient cycling, etc.

In this toolkit, we contrast the ecosystem services with ecocentrism. But we should be clear: advocates of ecosystem services usually don’t see themselves as indifferent to nature — quite the opposite! How would they answer their ecocentric critics? And how might the ecocentric critique develop in response? See Activity Seeds for more ideas exploring debates around ecosystem services.

-

What is Earth Jurisprudence?

What role does law play in ecological and social sustainability? How does nature relate to the law? How can our legal frameworks be improved to address environmental crises, and help us to live justly with animals, plants, insects, micro-organisms, rivers, mountains, ecosystems? How might legal controversies be ways into thinking through cultural presuppositions about the nature of nature? These are some of the questions explored by Earth jurisprudence, which seeks to recognise that humans as part of a wider community of beings, and that the wellbeing of every member of that community depends on the wellbeing of the Earth as a whole.

Cormac Cullinan has influentially suggested that the laws of the universe constitute a ‘great jurisprudence’ which is ‘neither right nor wrong’; an ‘Earth jurisprudence’ would be a set of legal theories ‘to a large extent derived from, and consistent with’ this ‘great jurisprudence’. Peter D. Burdon writes:

“In contrast to anthropocentric legal philosophies, Earth Jurisprudence represents an ecological theory of law. Central to Earth Jurisprudence is the principle of Earth community. This term refers specifically to two ideas. First that human beings exist as one interconnected part of a broader community that includes both living and nonliving entities. Further, the Earth is a subject and not a collection of objects that exist for human use and exploitation. […] This principle does not deny the moral status of human beings or claim that all forms of non-human nature have moral equivalence with humanity.8 Instead, it seeks to shift our focus away from hierarchies and asserts that all components of the environment have value. It takes the wellbeing or common good of this comprehensive whole as the starting point for human ethics.” (Burdon 2012)

-

What are Rights of Nature / environmental personhood?

Rights of Nature are an important aspect of Earth Jurisprudence. Non-human living entities have the moral right to exist and to thrive—so shouldn’t they be able to turn to the courts for justice, just like people can? Environmental personhood is now emerging in some jurisdictions. This designates certain environmental entities (for example an animal, a species, a river, an ecosystem) the status of a legal person. For example:

Fluvial ecosystems have been at the heart of some of the most emblematic cases pushing forward the frontier of what has been called a ‘rights revolution for Nature’ […] This ‘revolutionary’ shift is displayed, for example, by the case of the Whanganui River in New Zealand, whose legal personhood was recognized through a legal entity called Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) Act 2017 New Zealand. […] Similarly, there is the case of the Atrato River, located in Colombia, which was recognized in 2016 as an entity with legal personhood and the right to be protected, conserved, maintained and restored. (Charpleix 2018)

It’s easy to get confused about legal personhood, and the headlines often don’t help (“Should rivers have the same rights as humans?” “Science shows dolphins are people too!” — that kind of thing). Put simply, legal personhood just means possessing one or more legal rights. You don’t have to be a human to be a legal person — corporations have long been legal persons. As Steven Wise put it, some years ago: “Some people think we’re trying to get human rights for chimpanzees. We’re not. We’re trying to get chimpanzee rights for chimpanzees.”

A closely related concept is legal standing for nature, which means giving environmental persons the ability to litigate their grievances in court. But a river can’t appear in court—can it? Environmental personhood generally assumes that humans will act as guardians.

One criticism of this approach is that environmental persons may become vulnerable to lawsuits themselves.

Sussex Spotlight: The UK Earth Law Project

The UK Earth Law Judgments Project (Helen Dancer and Bonnie Holligan) addresses a critical global issue in a way that is new for the UK. Following in the footsteps of feminist judgments projects, and the recent Wild Law Judgment Project led by Australian scholars, the project reimagines important UK legal judgments from a range of perspectives within the field of Earth Law.

-

How do natural entities benefit from legal personhood? Are there other ways of protecting them?

Being a legal person doesn’t entail human rights (to life, to dignity, etc.) or anything resembling them. So by itself, legal personhood for natural entities will not necessarily curb exploitative treatment. It would depend on the precise nature of their rights, among other factors.

On the other hand, natural entities can (and already do) enjoy many legal protections without being legal persons. For example, in UK law animals are not persons. Animals are property. However, that does not mean owners can mistreat them. They are protected by animal welfare legislation (Animal Welfare Act 2006, and previously the Protection of Animals Act 2011). Animals that are “under human control” are protected from “unnecessary suffering.” It is also a legal offence to fail to provide care for an animal you are responsible for, including suitable food and water, and the chance to follow “normal behaviour.” The recent Animal Welfare (Sentience) Act 2022 legally confirms the sentience of a wide range of animals. Then there are criminal offences for polluting, and laws obliging environmental impact assessments. Do such laws acknowledge the intrinsic value of non-humans? This is an open question you could explore with students.

So why is there such excitement around Rights of Nature? Well, they don’t exist in a vacuum. These recent developments belong to the wider ecocentric movement (or set of movements). In this sense, they seek not only to transform statutes or introduce new precedents, but rather fundamentally to transform the cultural and ethical grounding of that law — to unleash fresh forms of reasoning and new structures of feeling to ripple through the law in ways that may be difficult to foresee. Do students see real revolutionary potential in the Rights of Nature movement? If Rights of Nature are increasingly recognised, how might extractivist power dynamics attempt to adapt?