22 Degrowth and Postgrowth

Modern economies are based on the theory of economic growth, but indefinite growth is not feasible in a finite planet. Degrowth and postgrowth are overlapping philosophies that recognise the need for profound socio-ecological transformation. There is indeed a limit to growth, so planetary boundaries and social wellbeing must be protected to avoid or limit possible tradeoffs. (See Doughnut Economics illustration under Theme 1 for more).

Degrowth is a movement to reduce the environmental impact of human activities, and tends to focus on reorganising patterns of economic activity, to reduce unnecessary human consumption, production, pollution, infrastructure creation, resource use, and trade. For example, some degrowth transitions to reduce pollution can aim to cap CO2 emissions, cap resource use and extraction, suspend new infrastructure, such as new nuclear plants, dams, and highways, promote organic farming, and tax activities known to destroy the environment to reduce waste generation (Cosme, Santos, and O’Neill 2017).

Proponents of “green growth” claim that we can decouple economic growth from environmental degradation, saying that indefinite economic growth eventually will become possible without crossing planetary boundaries. Degrowth and postgrowth advocates argue that this is not possible (or at least, not possible quickly enough to prevent irreversible ecological catastrophes).

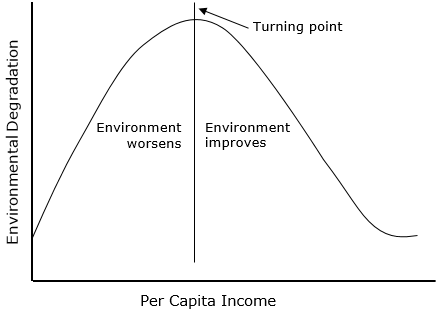

Sometimes the green growth argument visualises the Environmental Kuznets Curve. This claims that a country’s economic development initially leads to a deterioration in the environment, but after a certain level of development has been reached, it can afford to produce in more environmentally friendly ways. At this point, decoupling supposedly takes place. Even from the perspective of climate change alone, there are two big problems with this argument:

- 1) It probably isn’t true — the empirical evidence is mixed at best. Some countries, including the UK, do appear to have decoupled GDP growth from carbon emissions. But this is partly because the UK has deindustrialised. Many manufactured goods (and food, and other resources) are now imported. This strategy wouldn’t work for the planet as a whole.

- 2) We’ve got a tight carbon budget for limiting global warming to well below two degrees. Even if economic development really were reliably characterised by the environmental Kuznets curve, there is not enough capacity to keep pursuing fossil-driven development for a few more years. Global carbon emissions need to peak and start to fall right away.

Degrowth is a transformative initiative that proposes a reduction in production and consumption for wealthy nations, a reduction in material throughput reflected in prudent lifestyles and lean economy. Degrowth is also often connected with proposals to use alternative economic indicators (“Beyond GDP”), to measure what is really valuable, rather than using GDP growth as a proxy for all policy success. Think of degrowth as a practical reaction in support of climate and environmental justice. The target is to reduce the ecological impact of economic development, decrease economic inequalities, and improve the overall well-being of humans.

However, degrowth proposals have been criticised on the grounds that they do not apply to developing countries or countries in the Global South, considering their high levels of deprivation, inequality and conventionally slow economic growth rates. In reality, many developing countries are not willing to give up on economic growth as much as they yearn for ecological protection. In recent years, more work has been done to join up degrowth with decolonial work and postdevelopment theory. In this sense, degrowth challenges the standard development paradigm from a social as well as an ecological standpoint — observing the double-edged nature of development, which can both improve quality of life for many people in the short term, and yet further neocolonial power relations.

Irrespective of existing debates, the motive for degrowth is to improve quality of life and advance environmental sustainability. Degrowth emphasises changing priorities of society from economic growth and production to a society based on sustainability, wellbeing, concern for environment and co-operation.

Degrowth Proposals

-

Income and wealth redistribution both within and between countries

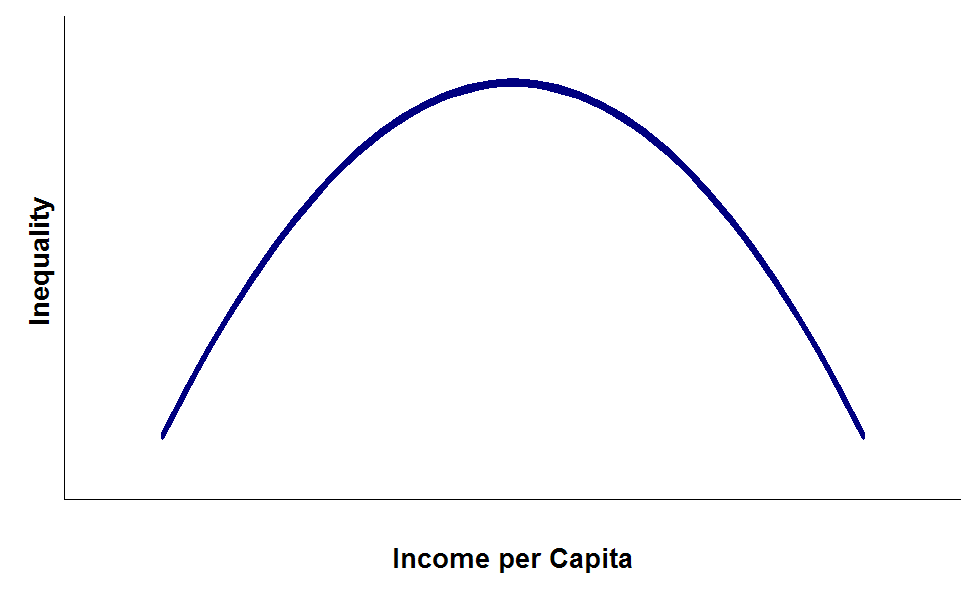

Policy proposals on the redistribution of wealth and income within and between countries tend to focus on four major domains, namely socioeconomic opportunities, equity, access to goods and services, and global governance (Cosme et al., 2017). Various forms of Universal Basic Income (UBI), also known as citizen’s income, have been proposed and piloted. These propose to delink income from wage employment to cushion individuals from uncertain market dynamics. Delinking the basic or citizen’s income from wage employment promotes access to goods and services, especially the socially important ones like food and healthcare. However, UBI is also controversial for many reasons, including the risk that it will be used to shrink public sector services. Furthermore, introducing maximum pay ratios or salary caps is likely to promote equity in wealth and income redistribution. Another strategy is reducing the size of companies to promote equity in income and wealth distribution whilst allocating differentiated responsibilities to the Global North and Global South. This is in line with feminist scholars advocating for the need to remain gender and geographically sensitive when implementing degrowth policies at a global level while paying attention to governance.

But differences in payslips is only a small part of the story. Income from capital (owning property, stocks and bonds, etc.) is currently a far more powerful driver of inequality. Reform of the finance sector, often including a strong progressive wealth tax, is also part of many degrowth programmes. There are other ideas such as promoting job sharing among the populace, reducing the number of working days in a week to guarantee work opportunities for everyone. Thus, redistributing wealth and income between and within countries centres around socioeconomic opportunities, equity, global governance, and access to goods and services.

-

Reduce environmental impact of human activities

As a concept that has transitioned to a movement, degrowth advocates propose reducing the environmental impact of human activities. This includes reducing unnecessary human consumption, pollution, infrastructure creation, production, resource use, and trade. For example, some of the proposals to reduce pollution aim to cap CO2 emissions, promote organic farming, and tax human activities known to destroy the environment. Kallis (2011) proposes the need to reduce overconsumption by regulating advertising, suspending new infrastructural development activities, putting caps on CO2 emissions, creating a strong and progressive tax system that targets environmentally damaging activities, mitigating large-scale and resource-intensive production, banning nuclear output and other activities that heavily damage the environment, regulating resource use and extraction, and putting more investment in sources of renewable energy. Along similar lines, Hall (2011) proposes regulating the tourism industry to protect the environment and incentivise local production and consumption. Therefore, policy proposals on environmental protection as a primary goal of degrowth primarily focus on reducing consumption and production, regulating resource use and extraction, curbing pollution, and enhancing trade’s social and ecological efficiency.

-

Transition from a materialistic to a participatory and convivial society

What might a convivial and participatory society be like? Advocates tend to focus on four major topics, namely: free time, democracy and participation, voluntary simplicity and downshifting, and community building, education and value change. No surprise here, because reducing working hours for everyone as proposed in the category of ‘Income and wealth redistribution’ will promote free time. Free time is a significant social indicator of quality of life, since it reduces dependence on economic activity. Apart from free time, degrowth crusaders suggest that people might embrace frugality to lower overconsumption and overindulgence. Because human livelihoods are interdependent, frugality and voluntary simplicity may pose risks: in practice, some people make their basic living by supporting the overconsumption of others. While frugality and efficiency are inseparable within the degrowth landscape, frugal lifestyles need to be voluntary, but policies that facilitate or encourage frugality are welcome.

Another proposal under this theme is the need to promote political participation, for example by creating caps on political and electoral spending. Other ways of promoting democracy and participation within a degrowth framework include creating democratic institutions tasked with advancing degrowth proposals, and making these democratic institutions independent. Democratisation of workplaces is another aspect of promoting political participation. Overall, there is consensus among degrowth scholars on a convivial and participatory society within a degrowth framework. Recommendations range from investing in socially important public welfare sectors, to enhancing value change and increasing investment in restoring and strengthening local communities.

Finally but most importantly, degrowth advocates propose the need to introduce and incentivise educational programmes on the ecological limit of the planet and sustainability strategies that can be adopted to reduce the risk of exceeding this limit … without forgetting the need to preserve and promote traditional language, techniques and knowledge as a way of community building.

4. Degrowth and postgrowth

Degrowth and postgrowth have a lot in common, and sometimes the terms may be used interchangeably. One way of looking at postgrowth is as a recent effort to rebrand, reboot, and refocus degrowth (since degrowth is by now a somewhat broad and heterogenous movement). Tim Jackson distinguishes degrowth and postgrowth quite strongly in his influential Prosperity without Growth (2009 and 2017):

The dilemma of growth has us caught between the desire to maintain economic stability and the need to remain within ecological limits. On the one hand, endless growth looks environmentally unsustainable; on the other hand, degrowth appears to be socially and economically unstable. […] [W]e need convincing macroeconomics for a ‘post-growth’ society. One in which neither economic stability nor decent employment rely inherently on relentless consumption growth. One in which economic activity remains within ecological scale. One in which our ability to flourish within ecological limits becomes both a guiding principle for design and a key criterion for success. […] [D]egrowth advocates have no problem at all accepting the first horn of the growth dilemma: that growth is unsustainable. But they tend to deny the validity, or at least diminish the importance, of the second. Degrowth is not necessarily the same thing as negative growth, argue its advocates. And so it doesn’t have to lead to instability. But this isn’t an entirely satisfactory answer – in part, because it gives us too little to go on in building a post-growth macroeconomics.

In Doughnut Economics, Kate Raworth suggests “growth agnosticism” rather than degrowth.