Active Essay Writing: Encouraging independent research through conversation

Heather Taylor; Wendy Garnham; and Thomas Ormerod

Outline of case study/project

In an educational forum increasingly dominated by league tables and exam performance, students entering Higher Education are faced with a significant challenge of moving away from “spoon-fed recipes for success” to adopting “self-learning skills” (National Audit Office, 2002, p.15). Many enter university bringing a “reproductive” or “rote-learning” strategy with them, where learning is seen as a process of memorization (Wilson, 2018). Knowledge is seen as owned by tutors and learning is equated with “passive absorption” (Gamache, 2002, p.277).

The transition to a new form of “independent” learning, can be a major hurdle for many (Beaumont, O’Doherty & Flanagan, 2011) and contributes to a sense of alienation (Hernandez-Martinez, 2016) and failure (Haggis & Pouget, 2002). Lowe and Cook (2003) found that up to 21% of students in their sample reported difficulty with self-directed study that was greater than they expected and Haggis and Puget (2002) point to the “lack of preparedness” for learning in higher education. Academic difficulty has been cited by some (E.g. Tinto, 1996) as one of the most common reasons behind withdrawal from university education. Barefoot (2004) describes this as “Higher Education’s Revolving Door”. Essays are often rife with personal opinions or description which is at odds with the demands of the tutor for argument and analysis (MacLellan, 2004). Students focus on content is often at odds with tutors’ focus on argument (Norton, 1990).

The difficulty reported with essay writing assignments early on in a degree programme, contrasts with the views reported by students in the final years of their degree (Christie, Tett, Cree & McCune, 2016) where confidence in tackling essays is reported, suggesting a gradual process of accumulating knowledge and skills. The question then arises as to how such skills are promoted and developed in students.

Until recently, models of skill development relied on the deficit model (Wingate, 2007; Haggis, 2006). According to the deficit model, students are seen as lacking the competence to produce academic work of the standard required so courses and/or training is required to enable this gap to be filled. However, although study skills courses are frequently provided, these are often seen as generic and perhaps irrelevant to specific courses so are avoided (Durkin and Main, 2002). Hathaway (2016) suggests that such courses are resisted due to the impression they give that an institution feels that there is a problem with students’ linguistic abilities and Wingate argues against their use completely, given the implicit assumption that these are an additional “extra” to the basic course requirements rather than an integral part of the course itself.

Rawdon (2000) instead promotes the use of reflection and opportunities to develop a deep understanding of the learning process as a means of enabling students to become autonomous learners (Fazey and Fazey, 2001). As writing is essentially a social act (Rubin, 1998), it has been suggested that collaboration and the development of learning communities might be an effective means of achieving this (Matthews, 1996; Tinto 1998).

The active essay writing project was an attempt to move away from the concept of providing “support” for essay writing and instead to trial a transformative approach (Hathaway, 2016). Rather than expecting students to research their essay title and then attempt to extract their arguments from this, students were encouraged to generate their own thoughts and opinions about an essay title before using research to support, refute or justify these arguments. Such an approach transforms students’ thinking from “How do I summarise the research that already exists?” to “What arguments can I generate and is there any evidence to support or refute them?”. It allows students to bring their own experience and understanding to the task before moving them to a deeper level of understanding based on research evidence.

The project was trialled with a cohort of Foundation Year students studying a Psychology module that explored Applied Psychology specifically. At the beginning of the module, all students were given access to a document prepared by Professor Tom Ormerod which detailed an approach to essay writing that moved away from reading then writing, to thinking and planning before reading. This document underpinned the active essay writing activities that students were asked to try.

The “How to’’ Guide (in 10 easy steps)

- Modelling the process. Present students with a hypothetical essay question. Ask students to suggest three general themes/ ideas that might be useful to explore in answering the hypothetical question

- Give students a selection of essay titles and ask them to select one that relates to their interests.

- “The casual conversation”. Ask students to imagine they are in conversation with another person and the topic under discussion is their essay title. What sort of arguments might arise? If you present one argument, what might the other person say to contradict this? Is there any additional argument to be made in support of what you have said?

- Ask students to narrow down the arguments into two or three “themes” or groups.

- Using the hypothetical essay question, model the process of adding structure to an essay. Identify a minimum of one “for” and one “against” argument for the topic and model how to structure this into a meaningful response using either a mind-map, infographic, flow diagram, or similar.

- “The geographer’s dream”. Encourage students to create a structure for their own essay.

- Using the hypothetical essay question, model how to research peer-reviewed journal articles and books to identify relevant and appropriate evidence.

- “Sling your hook!”. Ask students to use the tools demonstrated in step 7, to help them research evidence for their own essay structure.

- “Let the story flow”. Ask students to take some of the arguments, now with evidence, from the hypothetical essay title and put them in a logical order to give the idea that there is not one correct way of using the information obtained.

- Model the process of moving from structure plan to finished product. Show an example paragraph for instance and demonstrate how the structure plan translates into the finished product. Ask students to work their way through their structure plan, now with evidence linked, to produce their final written response.

What we did

This project began when we recognised students’ confusion and anxiety around not knowing where to begin with their essay assignment. Some students were attempting to read everything on the general topic of their chosen essay title and were getting lost in not knowing what was and wasn’t relevant to consider. Other students were realising the unachievable nature of this task, and thus giving up at the first hurdle and opting to not read anything at all. Ironically, the latter pupils probably had the right idea! While it might make sense at A-Level to read a given chapter and then write an essay based largely on regurgitation of that chapter, that is not what is expected at University. In the same vein however, while university assignments often require students to read and write about peer-reviewed research, it would not be possible (or practical) for them to read everything available on a certain topic before beginning to write their assignments. Increasingly there is a need to train students in how to avoid plagiarism and this is easier when they are freed from the onus of engaging in huge amounts of reading and then having to decide how to use that in an original format. As such, we presented students with the alternative they had not yet considered.

Step 1

We began by presenting students with a hypothetical essay question; in this example we used the question ‘’Is dog man’s best friend?’’. This was selected as it was distinct from the core content of the module so could not give any student a particular advantage in their planning and preparation for the assessment. In their seminar groups they were asked to help their tutor come up with three general themes that could be used to help answer this question. Students came up with a variety of different themes including ‘’people’s feelings towards dogs’’, ‘’usefulness of dogs’’ and ‘’factors associated with owning a dog’’. We then asked students to come up with potential arguments that could support or refute the idea that dog is man’s best friend, within the themes they had suggested. With some prompting from the tutors, students were able to come up with some potentially relevant arguments and counter-arguments. For example, for the theme of ‘’factors associated with owning a dog’’ students suggested benefits of dog ownership such as them offering companionship and helping to keep their owners active, as well as potential drawbacks of owning a dog such as cost and time commitment. The emphasis here was on getting students to generate thoughts and have confidence in their own ideas before the opportunity to read academic articles and feel constrained by what they had read, had set in.

Step 2

Students were asked to look at a selection of essay titles, all of which had relevance to the key content of the Spring Term course, a module on applied psychology, and to identify the one that they were most interested in taking forward as their summative assessment topic.

Steps 3 and 4

At the following seminar, students were asked to sit in pairs or small groups of three and hold what we called the “casual conversation”. Students would take it in turns to ask each other their essay question and assist them with prompts and follow-up questions to identify general arguments they could consider as well as viewpoints for and against these. They were asked to imagine that the conversation was about their essay topic and they had to identify as many different ideas and arguments as possible, similar to what had been modelled in step 1 for the hypothetical essay question. Towards the end of this seminar, students were asked to use the information and ideas gained from the conversation, to identify two or three key themes or groups of arguments to use in their essay. At this stage, it was again emphasised to students that they should not be engaging in any reading around this topic yet as the purpose of the activities was to generate their own thoughts, opinions, arguments and ideas without constraint.

Step 5 and 6

In the next seminar, we modelled the process of adding structure to our hypothetical essay arguments. We used the dog example, to show how the arguments could be organised in the form of a mind-map to show the outline of the essay. Students were also introduced to infographics as an alternative way of organising the arguments. Following this, they were given the opportunity to have a go at structuring the arguments identified using one of these (or a similar) method. The idea is that at this point, students have not begun to read around the topic. They are simply constructing a meaningful narrative that incorporates their own thoughts and opinions and has a sense of logical structure to it. The structure itself should serve as a starting point for reading and research.

Steps 7 and 8

The next task (for both the tutor and the students!) was to independently find reliable research evidence to support their arguments and counter-arguments. In the seminar, we demonstrated some of the ways that reliable research evidence could be identified using library search tools and tools such as Web of Science and Google Scholar. As part of this modelling process, we emphasised to them how to determine whether a reference is credible and how to reference these sources correctly as well as how to use appropriate search terms.

We advised students to spend no longer than half an hour trying to find research evidence for each argument, suggesting that if they could not find anything within this time frame, then it was possible that no such evidence existed. We emphasised that not finding evidence for every single potential argument they had considered was not an issue, and just to use what they could find to help them think up other potentially relevant arguments and counter-arguments to find evidence for. We also advised students not to read too widely. Their task was simply to find one piece of evidence for each of their arguments and to summarise it on their Mind Maps or structure tool used; at this stage they did not need to know all the ins-and-outs of a piece of research, they just needed to know that research existed (or didn’t) to back-up their proposed arguments.

Step 9

While students had been collecting evidence for their own essays, their tutors had been doing the same for the hypothetical essay question of ‘’Is dog man’s best friend?’’. In the students next seminar session, they were presented with each of these pieces of evidence on separate pieces of paper and asked to work in small groups to arrange them in a way that facilitated a logical sense of flow. There were two key purposes of this activity. Students who come straight to University after studying A-Levels often seem to think the only way to present for and against arguments in essays is to dedicate the first half of their essay into ‘for’ arguments and the second half of their essay into ‘against’ arguments’ (or some paragraph-by-paragraph variation of this). While this technique is helpful for ensuring a balanced essay, this way of presenting information does not necessarily lend itself to a seamless sense of flow and can seem rather rigid and disjointed. Secondly, when identifying more than one theme, we envisaged that students would similarly get stuck in presenting their essay content one theme at a time and this activity enabled us to show students how the overall flow of information was important.

Once students had completed the activity, tutors went around to each group and asked them to explain what order they thought the arguments should be presented in. The tutor then presented them with their own ideas for how they thought the essay could be structured and emphasised that there is not necessarily one ‘’right’’ way of doing this – in fact students and tutors often had arguments presented in a slightly different order – but rather, if the arguments flow into each other, then the job is done correctly.

Step 10

Once students had completed the above activity and realised that they need not be restricted in structuring their evidence in order of argument type or theme, we asked them to independently structure the pieces of evidence for their own essays. We explained to them that in doing this they could see if/ where points and pieces of evidence were unable to flow into each other. We explained that this could be due to certain pieces of evidence not fitting the general narrative of their essays (and hence they might wish to consider dropping these pieces of evidence) or due to insufficient evidence being presented and thus they could use this knowledge to find additional evidence to bridge the gaps.

In doing this, students had a ‘bare bones’ outline to follow for writing their essays. Their next job was to flesh out the skeleton, with important details of research, and further evidence-based interpretations to make for a well-rounded, evidence-based and highly-focused piece of writing. Again this was modelled with example paragraphs for the “dogs” essay title. Students could then use the planning and preparation to guide their own writing for their actual assessed essay.

The successes (what worked well)

From our perspective, many things appeared to go well. Students who appeared invariably confused and anxious at the prospect of reading everything ever published on the given topic of their essay title, were able to realise that doing this was neither expected or encouraged by their tutors. A-Level education arguably taught many of these students to read first, write second but fails to consider the overwhelming scope for reading in Higher Education, while neglecting the pivotal element of thinking! As such, we redirected students towards a new way of producing essays, namely thinking and discussing before reading and writing. Such an approach enabled students to take a personal interest and investment in their writing as it offered a means of showing that their own values and opinions are valid and worthy. The move away from the idea of a “model answer” or a “correct response” was refreshing for both students and tutors and this was reflected in much of the feedback received from students in their end of term review. When asked what they had most enjoyed about the seminars for this module, students’ responses included:

“I like the ideas which are brought up and how we are encouraged to think outside of the box, able to present any idea without restriction”

“The support for creativity in writing the essay”

“I’m finding that it is supporting the way I would normally write an essay so it is not shocking or scary”

Another key benefit of this project was that both the students, and us as tutors, could monitor their progress. It is probably quite common, especially as students progress through their University careers, that they are given an essay topic at the beginning of a term and the next time tutors hear of this essay is when they are marking it at the end of term. While this approach is arguably fine for those students who are already well-established in their Higher Education studies, for those who have either not written a university-style essay before or not written in this style for some time, more structure and support are needed. Breaking the essay preparation down into stages, as we did, not only enabled us to monitor our students progress and to realise when and where they were getting stuck, it also enabled students to identify if they were ‘’keeping up’’ with the work. This can be very useful to new students, as while they might be informed of when to attend lectures and seminars, and what reading they should do in preparation for these, they are less likely to be guided around what assignment work they should complete and when. The success of this project was reflected in students’ ratings of the seminars for this module at the end of the term. In 2017-18, where traditional essay writing practice was used, 60% of students rated the seminars as either “Great-really enjoyed them” or “Most were engaging and some were useful” with 4.6% saying they did not enjoy the seminars at all. In 2018-19, with the active essay writing project in place, 75% rated the seminars as “Great” or “most were engaging” and not a single student said they did not enjoy the seminars at all, even though a greater proportion of students completed the survey.

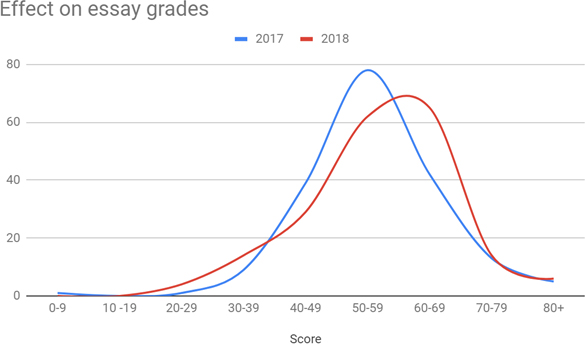

Lastly, the biggest success seemed to be that we received some fantastic essays that really raised the bar in terms of what we assumed our students were capable of. Some of the essays we marked were of excellent and even outstanding quality; with students thinking outside of the box and drawing relatively novel conclusions from the research they presented, while also producing work that flowed well and was immensely engaging to the reader. In terms of overall performance, the effect on summative assessment scores was interesting. Although we have to remember we did mark these which is potentially an issue, we did so as blind markers and sticking strictly to the detailed mark scheme so the potential for bias was minimised in this respect. As far as the extreme ends of the mark scheme were concerned, the active essay writing project appeared to have little effect. However, it was towards the middle of the mark scheme that students benefited the most. Whereas the previous year, the most common score was in the range of 50, for the term in question, the most common score was in the range of 58-60, suggesting an upward shift of scores.

The unexpected difficulties (what went not so well)

It would be naïve to call it unexpected, however one of the key difficulties we faced was students not completing preparatory work on time. The project is deliberately set in pre-determined stages. As such, for a student to fully benefit from each seminar and lecture dedicated to the essay assignment, it was important that they had completed the previously-set work in advance of the subsequent sessions. While tutors are unable to dictate what students do outside of lessons, two possible solutions exist to grant tutors better control of students’ time management. Firstly, we could try to set more time aside within lessons for students to complete essay preparation work. If this were not possible, another option would be to set formative deadlines where students could submit work for feedback, which might motivate them to keep up-to-date with the work they are set. An alternative explanation is that we did not allow them enough time to complete this work in the first instance. Seeing as tutors completed the work alongside students for the hypothetical essay questions, this explanation seems unlikely, however in future we may wish to begin essay preparation work earlier in the term, giving longer for students to complete each stage, to see if this is beneficial.

Another issue is that some students appeared resistant to the change in approach to essay writing. Some students found it difficult to comprehend how they could think up themes and arguments without reading widely first. It must be said that not all our essay question options lent themselves as well to the model as others, however it was not impossible to think up general themes and potential arguments even for the least-well-known topics. One of the barriers to our new approach was the reliance that students had had instilled in them, on model answers.

Whilst we had some outstanding essays, we also had a considerable number of essays that appeared to be of A-Level standard. Many followed the traditional argument/ counter-argument structure with little attention paid to whether points flowed in a logical order and a lot of points and arguments were made without citation to any relevant research evidence and/ or based largely on opinion. Some essays not only followed the A-Level structure, but also the A level curriculum, citing outdated studies from text-books instead of peer-reviewed research evidence to support the contemporary essay questions students were assigned. As such, it may be naïve to think that one term of teaching is enough to help all students successfully transition from further education to meet the needs of higher education assignments. That being said, it appears that some students were fully ready to make this transition, with excellent outcomes, and even for those who did not fully meet the challenge, this can be considered as a first step in the leap between secondary and university education and expectation.

References

Barefoot, B. O. (2004). Higher education’s revolving door: Confronting the problem of student drop out in US colleges and universities. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 19(1), 9-18.

Beaumont, C., O’Doherty, M., & Shannon, L. (2011). Reconceptualising assessment feedback: a key to improving student learning?. Studies in Higher Education, 36(6), 671-687.

Christie, H., Tett, L., Cree, V. E., & McCune, V. (2016). ‘It all just clicked’: a longitudinal perspective on transitions within university. Studies in Higher Education, 41(3), 478-490.

Durkin, K., & Main, A. (2002). Discipline-based study skills support for first-year undergraduate students. Active learning in higher education, 3(1), 24-39.

Gamache, P. (2002). University students as creators of personal knowledge: An alternative epistemological view. Teaching in higher education, 7(3), 277-294.

Fazey, D. M., & Fazey, J. A. (2001). The potential for autonomy in learning: Perceptions of competence, motivation and locus of control in first-year undergraduate students. Studies in Higher Education, 26(3), 345-361.

Haggis, T. (2006). Pedagogies for diversity: Retaining critical challenge amidst fears of ‘dumbing down’. Studies in Higher Education, 31(5), 521-535.

Haggis, T., & Pouget, M. (2002). Trying to be motivated: perspectives on learning from younger students accessing higher education. Teaching in higher education, 7(3), 323-336.

Hathaway, J. (2015). Developing that voice: locating academic writing tuition in the mainstream of higher education. Teaching in Higher Education, 20(5), 506-517.

Hernandez-Martinez, P. (2016). “Lost in transition”: Alienation and drop out during the transition to mathematically-demanding subjects at university. International Journal of Educational Research, 79, 231-239.

Krause, K. L. (2001). The university essay writing experience: a pathway for academic integration during transition. Higher Education Research & Development, 20(2), 147-168.

Lowe, H., & Cook, A. (2003). Mind the gap: are students prepared for higher education?. Journal of further and higher education, 27(1), 53-76.

MacLellan*, E. (2004). How reflective is the academic essay?. Studies in Higher Education, 29(1), 75-89.

National Audit Office (2002) Improving Student Achievement in English Higher Education. Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General, HC 486. London: The Stationery Office.

Norton, L. S. (1990). Essay-writing: what really counts?. Higher Education, 20(4), 411-442.

Rawson, M. (2000) Learning to Learn: More than a Skill Set. Studies in Higher Education, 25 (2), pp. 225–238.

Wilson, J. D. (2018). Student learning in higher education. Routledge.

Wingate, U. (2007). A framework for transition: supporting ‘learning to learn’in higher education. Higher Education Quarterly, 61(3), 391-405.