A Tango for Learning: An innovative Experiential Learning format using Embodied Learning

Margarita Steinberg

Outline

This chapter presents a method for investigating complex situations through the medium of movement. This method is inherently inter-disciplinary, as it uses a format that originated in a practice for teaching improvisational dance (Argentine Tango). It lends itself particularly well to exploring the interpersonal aspects of any discipline practice (e.g. the study of International Development) and also of teaching practice.

The format fosters experiential learning that can complement and enrich text-based learning. An exploration of potential uses for learning about International Development highlighted how creating an embodied representation of the concepts and dynamics under consideration created a new level of personal understanding. One student commented “I had read that the effort to coerce a community group by a government agency can inadvertently create a drain on the agency, but that had remained an abstract concept for me. Having attempted to coerce a partner to move while they were not cooperating, in this format, has given me a vivid, visceral sense of what that paragraph in the textbook had been talking about.”

Creating tangible embodied expressions of theoretical concepts is one use of the format. Another application is for investigating situational problems and devising potential solutions that draw on more than formalised data and instead integrate information on interpersonal, emotional and intra-personal aspects as well. This may be particularly relevant to disciplines such as Business and Leadership, and also all of the Humanities. The format has particular affinity with the themes of teamwork, problem solving, and enhancing interpersonal skills. Interactions between tutors and students, within groups and teams, larger-scale configurations at organisational level, and more abstracted notions, such as the relationship between a company and its founder, can all be investigated using this format.

In this type of application, the goals of the session would be:

- Making available information about aspects of a situation, increasing awareness of the emotional, interpersonal and intrapersonal elements present

- A way of devising and testing options for future action

This chapter is aimed at readers interested in learning both a technique for embodied interactive learning and some of the theory that underpins it. The examples reported are largely drawn from situations where participants are reflecting on workplace relationships that are not functioning optimally. These are chosen to

>illustrate the general technique in a way that most people can appreciate, but are not intended to signal a limit to the scope for applications of the technique.

This chapter is organised into three main sections. First, there is a brief introduction to various theories that have a bearing on interactive embodied learning. The idea here is to point the reader to more detailed sources on these theories, but not to cover the theories themselves in great detail. The next section is a practical guide to conducting a particular kind of interactive embodied learning, based on the physical interactive movement of the participants themselves. The final part of the chapter offers some thoughts about the value of this approach derived from a workshop conducted at the 2nd annual Active Learning conference at the University of Sussex in June 2018.

Interactive Embodied Learning

Any interpersonal situation will involve, at the basic level, at least two autonomous agents and a connection, their shared context. This is reflected in the configuration taught initially in this format – two people with a point of contact. The configuration is also relatively undemanding on the co-operation skills of the participants, in movement terms, which makes engaging with the format more accessible.

Argentine Tango danced improvisationally qualifies as a dynamic complex system. Briefly, a dynamic complex system is composed of autonomous agents, and exhibits four key attributes: diversity, connectedness, interaction and adaptation (Rickards, 2016). This underpins its affinity for modelling other dynamic complex systems and situations, and for exploring phenomena such as distributed leadership. Interpersonal intelligence (insight into what is going on between us and other people) and intrapersonal intelligence (insight into how we’re operating inside) has been demonstrated to be enormously important in the workplace, as well (Wilber, 2000).

Deep learning is required to change how people act. This is particularly true for changing how people act in challenging situations. Hence in education today we need learning formats that can foster personally meaningful learning that impacts the short-term and the long-term evolution of a person’s conduct. The approach presented in this chapter, therefore, seeks to move away from a focus on declarative knowledge (which is readily available in the modern environment) or on right-or-wrong answers (which are insufficient for negotiating complex challenges with an emphasis on needing to generate new solutions), and towards promoting deep learning resulting in functioning knowledge, to use a distinction formulated by Biggs (see e.g. Biggs and Tang, 2011).

Precursors & situating this approach

Active Learning approaches

Bloom (1956) refers to the three learning domains of knowledge, skills and attitudes (KSA), also known as Knowledge-Skills-Self. The learning format presented in this chapter addresses all three levels, in particular its embodied nature binds these three levels together through the experiential format.

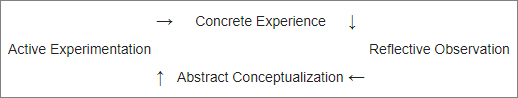

Guided Discovery Learning and Experiential Learning inform the practical shaping of this learning format. In particular, David Kolb’s (1984) Experiential Learning Model illustrates the sequence of steps used:

The details of how this conceptual model was applied are discussed in the How-To guide section.

Creative practice

Translating from one idiom into another, or into a different medium, is an accepted practice in the creative arts as an approach to exploration. In Drama this approach might inform the task to re-tell a novel as a script for a five-minute silent movie. Translating situations (which people generally describe using language) into an embodied medium takes them out of familiar narratives and prompts a fresh look.

Embodied cognition

This learning format involves a type of embodied cognition. Briefly, one type of embodied cognition can use physical representations of what is being thought about (an example of this might be chess, where the figures and the field represent two warring states and the terrain of battle). In contrast, this format uses the participants’ bodies and movements metaphorically to represent the characteristics of a specific situation, in order to explore its dynamic properties and the options for action. To flesh out what this might mean in practice, consider the example of a founder of a community interest company (CIC) exploring the dynamics of leading his organisation. To model this scenario, one person could represent the founder and the other his organisation. The gesture and movement versus each other would model the characteristics of the interaction. On another occasion, a participant wished to model their current workplace situation versus her line manager. The interpersonal experience would be expressed in movement, creating an opportunity to recognise aspects of the situation that had not yet become apparent to the person in the situation.

The field of psychology

The psychology modality of Gestalt (see e.g., Koffka, 1935) posits that our sense of a situation contains a lot of information in a diffuse format that Gestalt refers to as ‘the Field’ or ‘ground’. To make that information more available to our conscious awareness, an expression needs to be found (referred to as ‘the Figure’) using the medium of any sensory sense, visual, auditory, etc. Once that information about the interpersonal and intrapersonal aspects of a situation is available to our conscious awareness, expressed in a metaphor or symbol, we can work with it in a more intentional manner. Even simply recognising what they already knew in some way commonly triggers an ‘aha’ moment for people. The learning format presented here focuses on expressing the information in the field through the medium of movement or gesture. Constellation work (Cohen, 2006), originally developed by the German psychotherapist Bert Hellinger for family therapy, and Systemic Coaching, similarly work with spatial expressions of relationships. The learning format presented here takes this into a more dynamic direction, which readily permits not just an expression of the current situation as perceived by the participants, but also options for acting within the situation, facilitating devising a course of action to introduce change.

Systems and eco-systems

The familiar metaphor of organisations as machines is losing ground with an increasing recognition that an eco-system comes much closer to describing the properties of a community of living entities (Bragdon, 2016). Tangible, personally relevant exploration of the dynamics of eco-systems is therefore relevant for anyone who is, or is preparing to be, functioning within an organisation – which is to say, the majority of those attending schools, colleges and universities.

Dynamic Complex Systems

Modern complexity theory began in 1960’s with the work of Edward Lorenz, an MIT mathematician and meteorologist (see e.g. Lorenz, 1963). A subset of complexity science investigates dynamic complex systems, described by James Rickards (2016) in his book ‘Road to Ruin’:

A dynamic, complex system is composed of autonomous agents. What are the attributes of autonomous agents in a complex system? Broadly, there are four: diversity, connectedness, interaction and adaptation (Rickards, 2016, page 11)

Many natural and human systems exhibit these characteristics, with one example being the traffic systems in a city. The complexity arises from the varied nature of the agents participating in the system (diversity), each acting within a shared context (connectedness) yet each making decisions based on their individual take on the situation (autonomy), with each action taken potentially influencing the decisions that other agents will make in the wake of it (interaction and adaptation).

A number of disciplines are currently using complexity science to investigate fields as diverse as economics, climatology, ecology and social systems (see e.g. The Health Foundation, 2010). It is a particular strength of the learning format presented in the chapter that it facilitates modelling and investigating dynamics within a complex dynamic system. Once I realised that an Argentine Tango dance event qualifies as a dynamic complex system, the possibilities of the learning format for exploring phenomena such as distributed leadership became a point of fascination for me.

Complex situations and the focus on ‘what could be’

This learning format fosters a nuanced exploration of complex situations and systems, and focuses on “what could be” rather than “how it ought to be” (the last tends to engage our expectations, whereas the first keeps us focused on discovering). Because of the relational nature of the format, it is most readily understood initially by applying it to real-life examples.

The founder of a CIC (mentioned earlier) began this process by putting into movement terms his experience of leading his organisation. He started out by taking the role of himself, with another person representing the CIC organisation. The founder’s portrayal in movement of his actions included a lot of jerky movements, which he described as “somewhat erratic and swinging from tight control to periods of uncertain focus when I would be tempted to launch lots of initiatives without a clear objective because I was feeling panicky and overwhelmed”. He then took the role of his organisation to get a feel for what it might be like to be on the receiving end of such lead input.

Rather than offering a prescription for ‘a better way’ of approaching his organisation (an equivalent of ‘how it ought to be’ input), the learning format facilitates an exploration of options, with the aim of showing respect for the person’s autonomy and for their greater awareness of the nuances of their particular situation. The CIC founder explored how he might prefer to interact with his organisation (‘how it could be’). He considered how he might adjust his stance, first trying out in movement terms the option of allowing himself to pause until he was clear on the next step. Finding this an appealing option, he then converted the new approach into his situation, by determining to treat his periods of wavering focus as an opportunity to reconnect with the intended outcomes for the next time period, rather than generating additional tasks which previously had reflected his temporary sense of confusion.

Preparing to run the workshop

You will need to have some minimal practical experience of leading and following, so that you can provide a demonstration to the group. A few minutes with a volunteer to help you try the instructions for yourself ahead of hosting the workshop would be ideal. Follow the instructions for setting up a connection, agree on the role you’ll try first, then swap. Reporting on your personal experiences exploring this format can be very encouraging to the learners at the workshop.

The “How to” Guide

The rhythm of the work: doing and reflecting

Active learning “involves students in doing things and thinking about the things they are doing” (Bonwell, C. & Elson, J. 1991). This is further refined by working through the stages of the Kolb Experiential Learning Model (see section on Active Learning Approaches). The sequences described work through two learning cycles (more details to follow). The sequence of activities that the participants are guided through could in addition be mapped using the revised Bloom taxonomy stages as:

Understanding -> Applying -> Analysing -> Creating (Learning Cycle 1) ->

Creating -> Applying -> Analysing -> Creating (Learning Cycle 2).

Outline (What happens)

Learners are guided to connect with their personal perspective vis-à-vis a situation they’d like to explore (or introduced to the elements of a discipline the session will focus on). They temporarily set this aside in order to gain an initial experience of the learning format. They are then guided to use the learning format to model the situation they are considering, and reflect on what the modelling process had revealed for them. Learners are guided to build up connections between the symbolic model and the real-life situations/discipline-based concepts being explored throughout.

Preliminary preparation

In order to set up personally relevant material for the Active Experimentation phase later on in the session, it is suggested that participants are initially asked to jot down several interpersonal situations that they would be interested in gaining a fresh perspective on. These would optimally involve two people, reflecting the shape of the activity to come.

Demonstration

Figure 3: The author demonstrating the Butterfly Lead.

A demonstration by the tutor is recommended as the first step, to introduce the practical aspect of the learning format. This involves the tutor pairing with one person (optimally someone with at least some prior experience of the format) to demonstrate setting up a connection (see below) and moving around as a unit. The participants are asked to clear a space where the demonstration can take place.

Experience at previous workshops suggests that it is best to demonstrate two kinds of connection, one involving minimal physical contact, and one that does not involve any physical contact at all. This provides the participants with options that are acceptable to them, and thus enhances the inclusivity of the activity.

Connection involving minimal physical contact

The connection between two partners can be through the fingertips of one partner resting lightly on the back of the hand of the other partner (this is based on a practice in Eastern martial arts sometimes referred to as ‘Butterfly Lead’, designed to train sensitivity and responsiveness).

Connection that does not involve any physical contact

If either of the partners within a pairing prefers to avoid direct physical contact, an intermediary object can be introduced that acts as a conduit for the exchange of information within the partnership. Objects such as a cup or a pencil readily lend themselves to this purpose: two people each holding one end of a pencil are connected spatially, and will receive information about their partner’s movements. Other objects can be pressed into service, with preference given to those that would not pose a risk of injury, i.e. fragile or sharp objects ought to be avoided.

Moving collaboratively

It warrants stating explicitly to the learners that the goal of the interaction is to jointly maintain the connection while their ‘unit’ negotiates moving around in the space. Unlike competitive formats, this one very much prioritises collaboration.

Instructions on leading and following

Repeated experience with the format has revealed the minimum necessary instructions to allow people to get started in practice.

Guidance for those about to play the leading part, aka ‘leaders’

- Expand your awareness to encompass the larger entity you’re going to lead to move, a new unit of the two people in your pairing. This bears some similarity to the switch from driving a car to driving a truck: the enlarged dimensions of your unit have to be borne in mind, you need to recognise moments when you will need to change speed or direction earlier, before they affect your partner, as well as keeping yourself safe.

Also, since you’re the primary determinant of where and how your pairing will move, you need to keep some of your attention on the developments in the space around you, so that you can pick a safe path of travel. You bear the primary responsibility for the safety of both the partners (and, by extension, of everyone else in the room) – so it is recommended that you have a clear view on your intended direction of travel at all times, so that you can see conditions ahead. - Move yourself, rather than attempting to move your partner. You will quickly experience that your partner will move themselves to maintain the connection.

- A reminder that one of your goals is to maintain connection with your partner. This means that you may need to change pace and slow down if your partner is having trouble keeping up with you, etc. Your task is to make moving together safely as easy as possible for both of you.

Guidance for those about to play the following role, aka ‘followers’

- As your partner moves around, it is easiest if you move in response swiftly, rather than delaying until the connection is strained and in danger of rupturing. This applies to taking a step to maintain distance as much as to rotating round to keep your partner roughly in front of you.

The optimal range of distance is indicated by a comfortable bend in both arms involved in the connection (yours and your partner’s): a fully outstretched arm indicates the distance is getting too wide, and a sharp bend at the elbow indicates that the distance is collapsing and likely to cause discomfort. - Agency of the ‘follower’ role

It is entirely possible that you will be aware of an impending collision or an approaching obstacle before your lead is. It is in the interests of your pairing for you to take action to prevent collision, i.e. slow down or stop; your lead will need to adjust to your action, which is likely to protect them, as well. Although your role is dubbed ‘the follower’, there are active contributions you can make, and this one related to safety is the first and most important.

Learning Cycle 1

Figure 4: Participants practicing the Butterfly Lead at the 2nd Active Learning Conference, University of Sussex

Initial Concrete Experience

Active experience with the format is introduced by pairing people and instructing them to set up a point of contact. It is worth reminding participants to establish within their pairing whether a connection with or without physical contact is agreeable to both parties. (At a previous workshop which only demonstrated connection using physical contact, one participant exited immediately after the first practical exercise; their swift exit was later revealed to be caused by their discomfort with the physicality of the learning format).

The pairings also need to agree who is going to play the lead first (partners will swap roles within the pairing, so that each participant gets to experience both roles within the partnership).

Between one and two minutes is sufficient duration for the initial experience. Playing a music track on low volume in the background is optional. There is no requirement for the participants to pay attention to the soundscape in the space, other than sounds that might alert the participants to an impending collision. It is helpful to suggest that people refrain from talking until after the active experience, however.

Option to act as observers

The option for participants to act as observers during a segment of the workshop, or for the entire session, is useful to posit early on in the workshop for a number of reasons. It enhances the inclusivity of the format, by accommodating those who would hesitate to get actively involved in an embodied exercise.

The second reason is that observers can actively contribute to the learning in the group, and this needs to be stated explicitly. Observers are in a position to perceive what participants may be too preoccupied with their immediate tasks to pick up on. The phenomenon of our scope of attention being limited, and potentially diminished by a high-priority preoccupation is described in the book ‘Scarcity’ as ‘mental bandwidth tax’ (Mullainathan & Shafir, 2013).

A third reason for someone to act as an observer for a portion of the workshop might be an odd number of participants. It is suggested that the tutor avoid making up the numbers by participating, as this limits their ability to recognise moments when they may need to intervene or give additional input. Instead, the ‘odd’ person can swap in with another if they wish to get some direct experience of at least some of the session.

Caveat: Although the option to act as an observer is useful, the learning from active participation is cumulative. This may make it harder for learners to join in later, without the benefit of personal experience of the earlier stages.

Dealing with collisions

If you observe that a lot of collisions are taking place, this is likely because people are prone to turning most of their attention to what is happening in their pairing. While understandable, this diverts their awareness from what is happening outside the space their pairing is occupying. This is a very natural response to the intensity of a first experience, and participants need to be reassured of this. Two prompts in combination reliably diminish collisions. The first is to point out that this activity is not a race, and the objective is rather to develop greater sensitivity and subtlety in coordinating with one’s partner. The resulting gentler pace allows people to notice their surroundings more readily, which sets up the second prompt reminding the participants, and in particular the leaders, to turn a greater portion of their attention to the changing available space around them. With the enhanced awareness of their environment, groups tend to harmonise their movements more readily. At this point, the tutor can also point out that a larger community is being enacted, an ‘us’ larger than the pairings, uniting everyone in the space in a ‘whole’, an entity operating on another level, which is also amenable to investigation and reflection (more on this later).

Initial Reflective Observation

After you’ve called an end to the initial experience, prompt the members of each pairing to discuss with each other (small groups discussion) how they have found the experience, and share any observations on what had gone as they’d expected and what had surprised them. This permits each participant to learn both from their own and their partner’s observations. The findings can then be pooled in a brief plenary discussion, which is also an opportunity to bring in those who had acted as observers, to make sure that they are included in the session.

Swapping roles

Participants have another go at the same activity, now playing the role their partner had played initially (for expedience, rearranging partnerships is delayed to a later stage). Re-stating the instructions for the leading and following roles is warranted here, as people would have previously focused on the detail they needed for the most immediate task they were preparing for. In addition, you can also invite each pair to swap tips they’d generated from the experience they’d just had (thus further validating the learning they had already generated).

Again, an experience between one and two minutes is sufficient, and should be followed by a discussion within the pairings and then expanded into a brief plenary, as before.

Additional Reflective Observation

If the larger community of the whole group is of interest, you can invite people to comment on the dynamics of the entire room.

Abstract conceptualisation

To assist with abstract conceptualisation, this is the point where a brief analysis of the system each pairing had represented can be offered, as two autonomous yet inter-dependent agents and an interface/connection point. This is relevant as preparation for the next task, which will ask the participants to design an experiment of their own.

Active Experimentation (preparation)

The participants are now asked to work in groups of three (mixing up the previous pairings) to generate up to 20 configurations of connection. The tutor can offer prompts that configurations of connection can involve different modes of contact: different parts of the body can be involved (e.g. elbows), different intermediary objects can be considered, no-contact connection could be devised etc. (see also Appendix A: Worksheet for generating 20 connection configuration, at the end of this chapter).

It is useful to encourage the learners to go beyond discussing concepts for configurations, and actually test out what they are envisaging. This activity can also be used as an opportunity to incorporate those who had acted in the observer role earlier, as there is scope for people to participate in group work without needing to enact the embodied experiment.

Once the initial ideas within each group have been explored, they can consider some prompts provided in the accompanying worksheet (see Appendix A) to stimulate further investigations. Once the time allocated for this activity has elapsed, the groups are asked to share the configurations they had devised (up to three configurations from any one group).

Learning Cycle 2

This learning cycle starts with the participants already equipped with a direct personal experience of the format and some conceptual understanding of its elements and capabilities. Learning Cycle 1 worked through the first four steps of the Bloom Taxonomy map. This is approximately related to the Kolb Experiential Learning Model in the following way:

Understanding -> Applying -> Analysing -> Creating (Bloom)

Concrete Experience -> Reflective Observation -> Abstract Conceptualisation -> Active Experimentation (Kolb)

Learning Cycle 2 is going to ask the participants to take their learning into new territory by starting with creating. This learning cycle starts by asking the participants to review the situations they had listed during the preliminary preparation and, within their groupings (they can stay with the same people as in the previous step), to choose which scenario they are going to model using the format. The participants are now equipped to exercise judgement on which scenario might lend itself better to consideration through the metaphor of movement. The person bringing the scenario to the group (the scenario holder) provides a detailed description to their group of the two people (the agents) involved and how they are behaving in the scenario and the flavour of how they are interacting with each other (the connection). The tutor can provide support to each small group in turn in considering the properties of each agent in the scenario and the physical movement that would best express the qualities of the connection as described by the scenario holder. The configurations generated during the previous activity can act as a resource of options to consider. This is the initial step (Creating) in the sequence outlined earlier.

This is often the stage when a sense of emerging clarity gets commented on by a participant. The participant who was disconcerted by a lack of steer from her line manager expressed a sense of relief at simply finding a way to name or voice what she had found so troubling: a shift from receiving clear guidance (which she portrayed by hands placed by the representative of the manager on the ‘subordinate’s forearms) to a “hands off” approach (portrayed by a shift to the ‘manager’s’ hands being applied on their partner’s back and then removed completely). The physical situation of the ‘lead’ person standing behind their follower and removing all contact palpably conveyed how “at a loss” the recipient of such a management approach might feel.

Once the design of their experiment is ready, the groups are instructed to carry out their embodied scenario in practice. One person in the group can act as an observer, or pairs within each group can take turns to run multiple repeats of their experiment. The groups can then discuss (among themselves and with the tutor) any observations on the model they had devised and implemented.

At this point, the element of Time (Abstract Conceptualisation in Learning Cycle 2) is pointed out: the experiment so far modelled a ‘how it is’ interaction between the agents. The participants are now asked to consider how the interaction could be changed over time, either by changing the behaviour of the agents, changing the connection configuration, or both. This introduces the element of dynamics, i.e. how things change over time. The participants have already explored a range of connection configurations they can now draw on. This can be supplemented by a worksheet listing some options for agents’ behaviour (see Appendix B: Worksheet on Options for interacting dynamically).

Groups can test a number of options for the development of the scenario over time, using different adjustments at each iteration, with a particular emphasis on the situation holder’s agency. To illustrate, the participant who had modelled her situation with her line manager would, at this point, be invited to test options for adjusting how she operated in the scenario. Thus, she could try turning around to look at the ‘manager’ to gain a stronger handle on the situation, or taking the lead by making contact herself, or expanding the horizons of enquiry etc.

The conclusion to the process would be to translate back into situational action the options discovered through the embodied exploration. This anchors the personal relevance of the learning process: the scenario holder now has new options for future action, as well as a visceral experience of how situational dynamics can be changed. A plenary discussion of the whole group’s experiences over Learning Cycle 2 can be hosted at this point.

Learning Cycle 3 (optional)

More advanced models using this format can consider situations involving more than two agents. A systemic-level model can express in embodied terms a situation involving, for example, an entire department in an organisation, or a larger group / community, e.g. a Student Society.

Creative medium

The capabilities of this learning format are open-ended, and it is best approached as a creative medium. This is to say that, rather than asking what it can or cannot do, it seems more useful to wonder how a given brief could be met and encouraging creative thinking to explore how an embodied representation could be devised for what you’re seeking to include, in the spirit of open-ended enquiry.

In the practical guide section of this chapter, I have limited the situations that participants were to reflect on to those involving just two individuals. This was a pragmatic decision, and does not represent a limit on the applicability of this learning format. The situations to be explored could equally involve more than two individuals, or the interaction of groups rather than individuals, or indeed the interaction between one set of ideas and another. Examples of these generalisations beyond two individuals include the example mentioned earlier of dynamics between a government body and a minority group in a state, or even the interplay between the individual needs of a learner and the demands of sequential teaching of a discipline.

To give an indication of some of the more expansive options, other elements of a system, beyond two agents and a point of connection, can be included in the model, building on the metaphor of an eco-system. The context in which a system operates could be modelled. As an example, the ‘landscape’ in which the agents act could include representations of obstacles restricting free flow of activity; the ‘climate’ (supportive/distrustful etc.) could be represented, for instance, by a soundtrack conveying a particular pace or mood. Conflicting messages within a system could be portrayed by a soundtrack setting one pace and ‘someone in charge’ clapping at a different speed, or giving instructions to speed up against a background soundtrack broadcasting a steady pace, and so on.

To illustrate, the participant considering her options for changing the nature of the relationship with her line manager could also expand the scope of the exercise to model how the whole department was configured, which could help identify previously unrecognised options or resources. In this example, the participant could add elements to represent the context in which her line manager operated and the constraints that emanated from the current situation at the department level. In embodied terms, a physical barrier could represent the limitations on the manager’s scope for action, or their movements could be ‘hampered’ or they could be given an additional task, representing some concern that was drawing their focus away from engaging with this colleague. In real life, this exploration played a part in the participant determining to negotiate a change of contract which shifted her into a different section of the department under separate line management. The inclusion of the previous manager’s context had elucidated that there was limited scope for how that manager could re-engage with the situation holder, and so pointed towards seeking a new position within the department. The greatest gain from undertaking this exercise was a shift from a sense of bafflement and impasse to a direction for action.

The successes (what worked well)

All participants to date have succeeded in grasping the metaphor of an embodied expression of an interpersonal situation. They were able to translate situational information into movement (concrete to symbolic) and convert options discovered through movement into action in the real-life scenario under consideration (symbolic into concrete). All participants have succeeded in leading and following in the dynamic environment, once a personally acceptable connection configuration was settled on. All participants succeeded in devising an embodied expression of a specified situation.

Some participants commented that their initial hesitation and apprehension at the embodied nature of this format gave way to feelings of excitement at the visceral sense of discovery they experienced. Others commented on enjoying connecting their pre-existing declarative knowledge to the more personal embodied experience.

The unexpected difficulties

A greater challenge has been found in the tension between an academic setting, with an attendant association of a minimum of embodied interaction, and an embodied relational learning format. This tension was exemplified by one participant opting out of the workshop after the initial concrete experience had concluded. Expanding the range of options for contact (e.g. through intermediary objects) and the option to act as observer may reduce the discomfort for some participants. It ought to be acknowledged, however, that it is still possible for the focus of attention on the emotional and interpersonal domains to trigger discomfort for some participants. If further accommodations prove insufficient, the person may need to sit out this session.

Concluding thoughts & looking ahead

The importance of addressing the affective aspects of the learning process and of functioning within society cannot be overstated. This work aims to contribute to an evolving body of practice creating innovative approaches to facilitating learning in such areas as team working, leadership and organisational development. I would be interested in developing further inter-disciplinary applications using this format in other arenas.

References

Biggs, J. & Tang, C. (2011). Teaching for Quality Learning at University, Open University Press.

Bloom, B. S., Krathwohl, D. R. & Marisa, B. B. (1956). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The classification of educational goals., New York, NY, USA, David McKay Company.

Bonwell, C. & Eison, J. (1991). Active Learning: Creating Excitement in the Classroom.

Bragdon, J. H. (2016). Companies that Mimic Life, Saltaire, UK, Greenleaf Publishing.

Cohen, D. B. (2006). “Family Constellations”: An Innovative Systemic Phenomenological Group Process from Germany. The Family Journal, 14, 226-233.

Koffka, K. (1935). Principles of Gestalt Psychology, New York, Harcourt, Brace and Company.

Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential Learning: experience as the source of learning and development, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, Prentice Hall.

Lorenz, E. N. (1963). Deterministic non-periodic flow. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 20, 130-141.

Mullainathan, S. & Shafir, E. (2013). Scarcity: Why having too little means so much, New York, Henry Holt and Company.

Rickards, J. (2016). The Road to Ruin: The Global Elites’ Secret Plan for the Next Financial Crisis, Brighton, UK, Portfolio Publications.

The Health Foundation (2010). Evidence Scan: Complex adaptive systems.

Wilber, K. (2000). A Theory of Everything: An Integral Vision for Business, Politics, Science, and Spirituality, Boulder, Colorado, US, Shambhala Publications.

Figure credits

| Figure 1 | Adapted from Kolb (1984) |

| Figure 2 | Downloaded from the internet

https://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/solutions/industries/smart-connected-communities/city-traffic/_jcr_content/Grid/category_atl_9054/layout-category-atl/anchor_info_471b/image.img.jpg/1509700255133.jpg |

Acknowledgements

I thank the participants at the ‘Experiential Learning of the Embodied Kind’ workshop at the 2nd Active Learning Conference, University of Sussex campus, June 2018 for their willing and engaged participation. In addition, special thanks are due to Madeleine Broad who assisted with demonstrating the Butterfly Lead, and to Stuart Robinson, University of Sussex, for the photography used in this chapter.

I’d like to thank Maria Kukhareva and Kathryn Hunwick at the University of Bedfordshire, for their collaboration in developing this work. My thanks also to Wendy Garnham and Tab Betts at the University of Sussex for their interest and support for this approach, and for organising the Active Learning Conference. My warm gratitude also to Judith Good, Kate Howland and everyone in the Creative Technology Group in Informatics at the University of Sussex for their support in preparing my 2013 TEDx talk ‘Dance Tango Life’ which, in retrospect, formed the foundations for developing the work presented here. I thank Benedict du Boulay, Paolo Oprandi and Lucy Macpherson for commenting on an earlier draft of this chapter.

Appendices

In practice, both the worksheets that follow are best printed out in the Landscape orientation, to provide more space for participants’ notes.

Appendix A. Worksheet for generating 20 connection configurations (in groups of 3)

| Aspects of connection: some prompts | Your group’s 20 (or thereabouts) designs |

|

Appendix B. Worksheet on options for interacting dynamically

| Actions and responses (some examples) | Your group’s experiment | |

Actions/responses from either party within a pair

|

Which actions/responses did your group try out (these needn’t be limited to the examples listed)? If time permits, also record some of your qualitative experiences/findings. |

Appendix C: Sample session plan (60 minutes)

| Time | Topics | Activity |

| 1 – 5 | Potential topics for participant design later | Write down 3 situations

where increased understanding / new ways of interacting would be desirable for you |

| 6 – 10 | Introduction to the session

|

|

| 11 – 20 | 1. First experience of the learning format

|

0 – 1 Demo + instructions

2 – 3 First go 4 – 5 Discuss in pairs 6 – 7 Swap roles 8 – 9 Discuss in pairs Include comments from observers, if present, throughout |

| 21 – 35 | 2. Explore configurations for connection (in groups of 3)

|

|

| 3. Consider options for responding from either position/role (Appendix B) | Groups try out their ideas or prompt the tutor to demonstrate dynamic responses | |

| 36 – 45 | 4. Design & run your own experiment

Optional: new groups of 3 Optional: Instruction for groups to select a situation from those jotted down at the start of the session |

|

| 46 – 55 | 5. Plenary discussion

|

Reminder: Include comments from observers |

| 56 – 60 | 6. Conclusion

|

|

| Close and depart |