The ‘Diamond Nine’: encouraging student engagement with graduate attributes

Dr Joy Perkins

What is the idea?

Graduate attributes are designed to make explicit the wide-ranging competencies that students are developing, to prepare them for further study, employment, and life beyond university. However, despite their widespread implementation in UK universities, graduate attributes are often presented as high-level, generic statements, which require student translation at the academic subject level. To support students to understand their meaning and to engage with graduate attributes, the ‘Diamond Nine’ active learning technique can be used. The technique facilitates students to discuss, collaborate, and contextualise their understanding of graduate attributes, to help students start to develop them, during their time at University.

Why this idea?

The ‘Diamond Nine’ technique is an established active learning approach, which involves students ranking and prioritising nine ideas, viewpoints, or pieces of information into what they consider highest to lowest importance (Times Educational Supplement, n.d.). In this case, the ‘Diamond Nine’ technique can help students to start discussing, interpreting, and ordering their own skills and attributes. Engaging students in this type of learning has many benefits, including motivating them to learn while also developing their higher order thinking skills (Vercellotti, 2018).

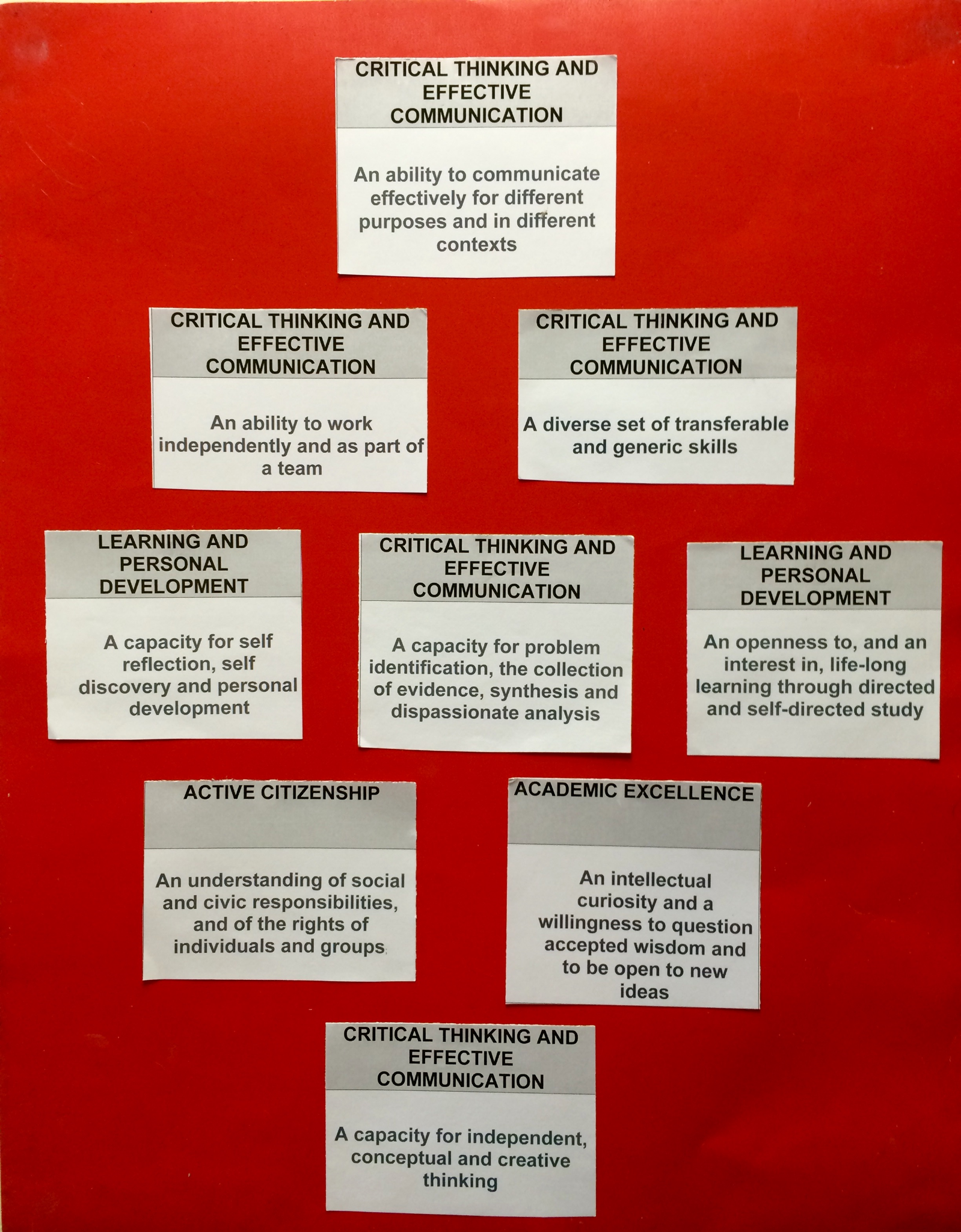

At the University of Aberdeen, there are 19 Aberdeen Graduate Attributes. Using the ‘Diamond Nine’ technique students can prioritise their top nine attributes into a diamond-shaped hierarchy (see image above). During this small group exercise, students are encouraged to reflect on their academic modules and their co-curricular learning. Discussing how and why they have prioritised and ranked the final ‘Diamond Nine’ is a central feature of this active learning approach. An important part of the exercise is also facilitating students to provide examples of how they have developed these attributes in their curricular and co-curricular learning.

Given the competitive employment landscape, it is crucial that students can demonstrate in-demand skills such as problem-solving, critical-thinking, and self-management to employers to fully enhance their employability. In the current economic climate, simply stating they have a particular competency is not enough (World Economic Forum, 2020). This active learning approach encourages students to engage with graduate attributes, helping students to interpret them in their discipline and supporting students’ articulation of these attributes to future employers or postgraduate recruiters. Interestingly and worthy of highlighting, is that Wong et al. (2021) in their graduate attribute mapping studies, also stress the importance of ‘decoding’ graduate attributes and helping students to understand their transferability in the workplace.

How could others implement this idea?

Limited resources are required to introduce this activity. Students are given a set of graduate attribute cards; each card contains a specific graduate attribute. Alternatively, Post-it® notes can be used and the results displayed on an A1 piece of card. It takes about 10 minutes to explain the rationale for the activity and to distribute the resources. Interestingly, Nguyen et al. (2021) advocate the importance of providing students with the rationale for using specific learning methods, as a crucial component for sustained and active learning.

The exercise can be completed by students working in pairs, or in a small group of 3-4 students. Students are asked to form a diamond arrangement, in which the top graduate attribute card in the diamond is most important. The second, third and fourth rows present the attributes with descending importance and the bottom attribute in the diamond is of least importance in the arrangement (see image above). Discussing ideas in pairs or a small group and agreeing on the top nine cards takes about 15 minutes. Each group should have a rapporteur to report back; sharing findings across groups can be useful to encourage graduate attribute discussion and debate. Typically, feedback to the wider class of approximately 20 students takes about 20 minutes. The session finishes with concluding remarks and next steps (10 minutes).

Overall, the activity takes approximately an hour. The exercise can be easily adapted across higher education institutions through universities preparing their own bespoke set of graduate attribute cards.

Transferability to different contexts

The ‘Diamond Nine’ technique encourages student collaboration, negotiation, and evaluation skills, so it is highly transferable across academic disciplines and contexts. For example, the technique could be used in Geography to stimulate discussion and enable students to reach a consensus on significant environmental impact issues, or in Art History to elicit dialogue around the importance and meaning of visual objects.

This active learning technique can be used with undergraduate or postgraduate students. However, to help encourage in-depth graduate attribute discussion with other stakeholders, the activity would be suitable for use with employers from different employment sectors and organisational sizes, academic staff, and other employability professionals (Perkins & Pryor, 2016). The relative importance of each attribute can again be illustrated through arrangement into a diamond-shaped hierarchy with the top line indicating the most important attribute for that particular stakeholder. Triangulating student findings against recent industry skills reports, or from data collected from employer contacts would add a different dimension to the exercise. Also, comparing the ‘Diamond Nine’ hierarchies of first year students and final year students may also yield surprises, debate, and different views regarding the relative importance of graduate attributes.

Links to tools and resources

- University of Aberdeen Graduate Attributes: https://www.abdn.ac.uk/graduateattributes/

- TES Diamond Nine Template: https://www.tes.com/teaching-resource/diamond-9-templates-11521827

References

Nguyen, K., Borrego, M., Finelli, C., DeMonbrun, M., Crockett, C., Tharayil, S., Shekhar, P., Waters, C., & Rosenberg, R. (2021). Instructor strategies to aid implementation of active learning: A systematic literature review. International Journal of STEM Education, 8(9). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-021-00270-7

Perkins, J., & Pryor, M. (2016). Graduate attributes and employer preferences. AGCAS Phoenix Journal, 148, 12-13.

Times Educational Supplement (n.d.). Diamond 9 templates. https://www.tes.com/teaching-resource/diamond-9-templates-11521827

Vercellotti, M. L. (2018). Do interactive learning spaces increase student achievement? A comparison of classroom context. Active Learning in Higher Education, 19(3), 197–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787417735606

Wong, B., Chiu, Y., Copsey-Blake, M., & Nikolopoulou, M. (2021). A mapping of graduate attributes: what can we expect from UK university students? Higher Education Research & Development, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2021.1882405

World Economic Forum. (2020). The future of jobs report 2020. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Future_of_Jobs_2020.pdf

Image Attribution

Figure 1. Photo of a ‘Diamond Nine’ set of ranked cards by Joy Perkins is used under CC-BY 4.0 Licence