Worth a fortune: active learning through origami fortune tellers

Nayiri Keshishi

What is the idea?

A paper fortune teller is a form of origami and was introduced to the English-speaking world in the book ‘Fun with paper folding’ (Murray & Rigney, 1928). Their use in children’s education has been recorded since the 1950s, mostly as a game or role-play prop (Opie & Opie, 1959).

This idea will demonstrate how the device can aid active and playful reflection within higher education, specifically for Foundation Year Psychology students.

Why this idea?

Playful learning has increased in popularity and is often used as a mechanism for improving engagement and motivation (Rivera & Garden, 2021). The nature of play, with its core socially negotiated aspects, places itself within social constructivism, where knowledge develops as a result of social interaction and language use (Walsh, 2015). Though typically associated with children’s education, it is a powerful method to integrate in the transformative learning process, where prior thoughts, knowledge or ideas are challenged. It allows students to practise, apply and fully understand key concepts; in this case reflective thinking and writing (Meyer & Land, 2006; Piaget, 1962).

Inspired by the use of origami fortune tellers as a module introduction or career development activity (Gillaspy, 2020), I incorporated them into a reflective thinking and writing class for Foundation Year Psychology students. As part of their module assessment, students were required to write a reflective journal discussing their personal and academic development. The purpose of the fortune tellers, and the accompanying game, was to support them in understanding the assessment marking criteria and applying it to various reflective writing examples.

The explicit playful elements of the game helped achieve a psychological acceptance of play, or ‘lusory attitude’ (Suits, 2005). As many of the students had encountered fortune tellers before, it also brought a sense of childhood nostalgia to the classroom. This feeling of excitement and human connection is an important part of encouraging a playful environment. This is vital for a learning space to appear as truly playful and for the activities to become meaningful (Nørgård et al., 2017).

How could others implement this idea?

Divide students into pairs and give time for them to familiarise themselves with the marking criteria and to read the three reflective writing examples.

Share fortune teller templates (one per person) and give students instructions (written and visual) on how to fold/make it. Also share instructions on how to operate the device and how to play.

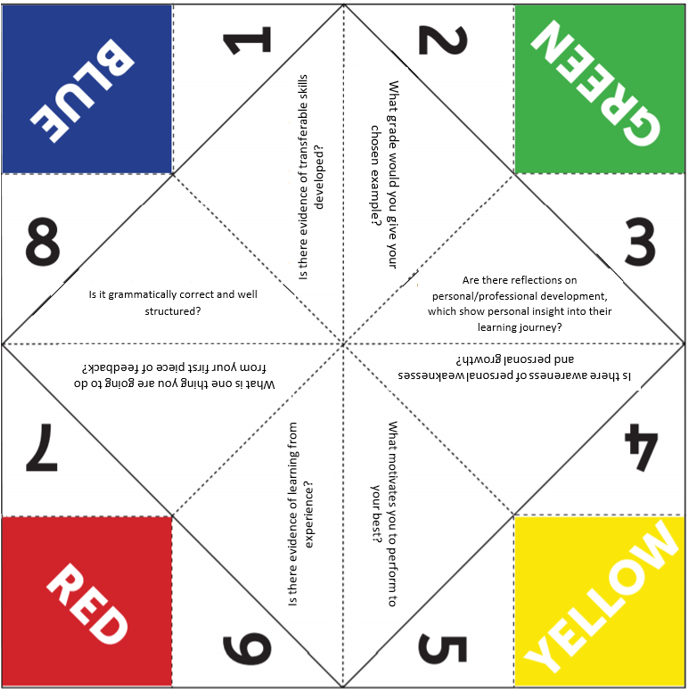

Before the class, parts of the fortune teller should be labelled with colours, numbers and questions that serve as player options (see Figure 1 as an example).

The person operating the fortune teller (player 1) should manipulate the device based on the choices of the other player (player 2). For example, if player 2 picks BLUE, player 1 would spell out the colour ‘B-L-U-E’ while working the fortune teller back and forth four times for each letter.

Then, player 2 needs to pick a number and player 1 works the device back and forth that many times. Player 2 should then choose another number and player 1 opens that flap to reveal/ ask one of the hidden questions.

The questions can either relate to the reflective writing examples or the student’s own work. Using the same language as the marking criteria, possible questions could be:

- Are there reflections on personal/professional development, which show personal insight into the learning journey?

- Is there evidence of developing transferable skills?

- What grade would you give your chosen reflective writing example?

Encourage students to discuss their answers and general thoughts, using the marking criteria to justify any comments/ grades, where applicable.

When one round is complete, instruct students to swap player roles. I would suggest 3-4 rounds per example, to ensure all reflective writing examples are discussed.

At the end of the activity, invite the class to share their thoughts and findings. Through discussion, most pairs should correctly identify which example is ‘adequate’, ‘good’ and ‘excellent’.

Transferability to different contexts

This activity can be adapted for any context. I would suggest readers:

- Provide clear instructions (written and visual) on how to make the fortune teller and play, as not all students will be familiar with the process.

- Practise making their own fortune teller, so you can help students if needed.

- Save the fortune teller template so you can edit/change questions for other activities.

- Try having students make their own fortune teller. This could be helpful for icebreaker activities, revision and consolidating knowledge.

For an online alternative, students could work in pairs or small groups using an online spinner. See Chapter 5b (Ready, steady…evaluate: using an online spinner to enliven learning activities) for further details.

Links to tools and resources

References

Gillaspy, E. (2020). Make along live: Experimenting with playful learning online. Creative HE. https://creativehecommunity.wordpress.com/2020/07/28/make-along-live/

Meyer, J., & Land, R. (2006). Overcoming barriers to student understanding: Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge. Routledge.

Murray, W. D., & Rigney, F. J. (1928). Fun with Paper Folding. Fleming H. Revell Company.

Nørgård, R. T., Toft-Nielsen, C., & Whitton, N. (2017). Playful learning in higher education: developing a signature pedagogy. International Journal of Play, 6(3), 272-282. https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2017.1382997

Opie, I., & Opie, P. (1959). The lore and language of schoolchildren. Oxford University Press.

Piaget, J. (1962). Play, dreams, and imitation in childhood. WW Norton.

Rivera, E. S., & Garden, C. L. P. (2021). Gamification for student engagement: a framework. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 47(7), 999-1012. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2021.1875201

Suits, B. (2005). The grasshopper: Games, life and utopia. Broadview Press.

Walsh, A. (2015). Playful information literacy: play and information literacy in higher education. Nordic Journal of Information Literacy in Higher Education, 7(1), 80-94. https://doi.org/10.15845/noril.v7i1.223

Image Attributions

Origami Fortune Teller Model by Nayiri Keshishi is used under CC-BY 4.0 Licence

Figure 1. Fortune Teller Template by Nayiri Keshishi is used under CC-BY 4.0 Licence