An institutional approach to active learning: lessons learned

Richard Beggs

What is the idea?

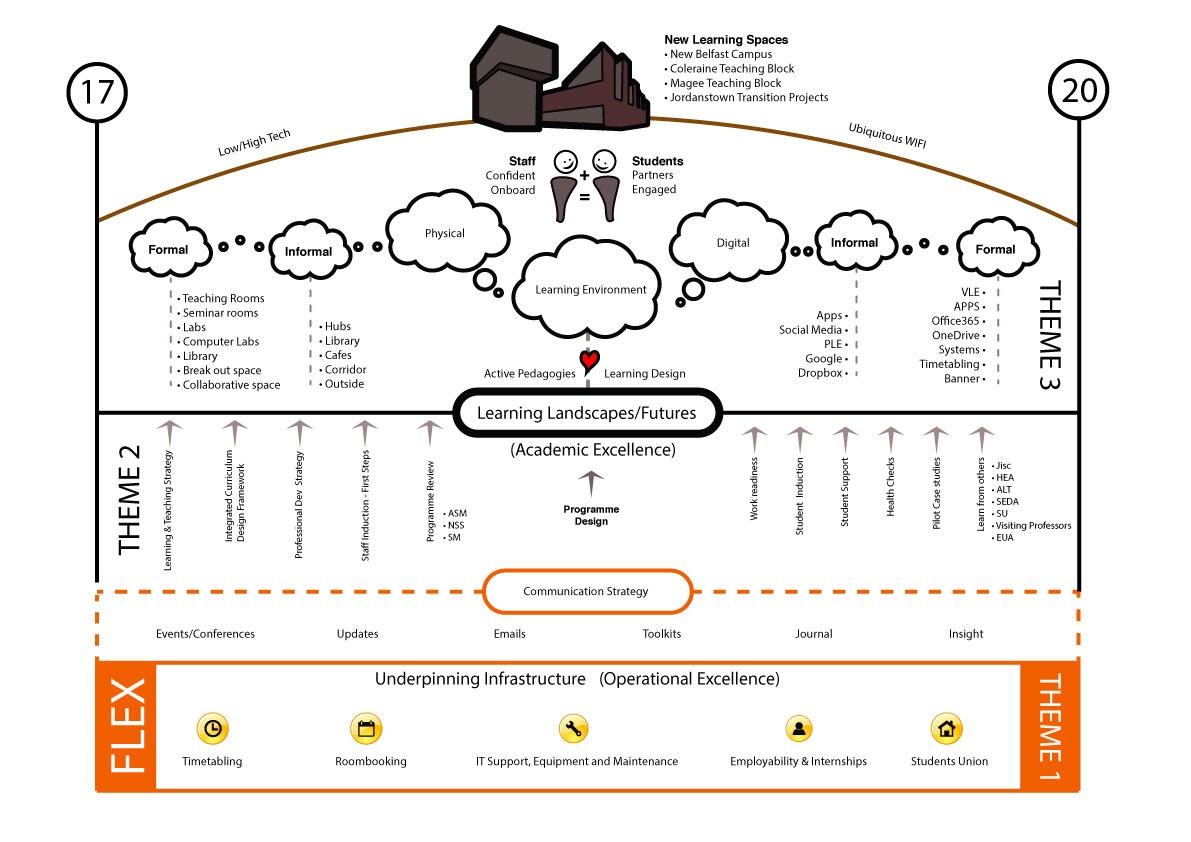

Ulster University is approaching the end of the development of its new campus in the centre of Belfast which will provide state-of-the-art physical and digital learning and teaching environments (Ulster University, 2020). This has provided the institution and its students and staff with a fantastic opportunity to evaluate our learning and teaching practices and to adopt a new approach across our physical and digital learning environments. An active and collaborative approach to learning and teaching has been adopted and has benefits to all students, removes gaps in student engagement, attendance, attainment and progression (Nottingham Trent University, 2019). This approach requires a significant amount of change in approaches to learning and teaching. Change is all about people, they are at the heart of change (Blake & Bush, 2009). In order to get staff and students on board with our learning and teaching aspirations the learning environment plan shown above in Figure 1 was created which puts people at the centre to provide a framework for strategic enhancement. This framework provided opportunities for staff to try something new, create staff/student collaborative partnerships, encourage active learning, learn from toolkits and training and to create safe spaces for both staff and students to experiment. This chapter will detail the approach and offer a lessons learned checklist for others who may be considering a similar approach.

Why this idea?

An evaluation was carried out in 2015, by visiting professor Jos Boys from UCL (Boys, 2017). This Learning Landscapes report identified several opportunities as well as common themes: underpinning infrastructure; institutional culture; and, learning and teaching practices. Recommendations indicated that more active learning spaces were required, as well as investment in staff and buildings. The Learning Environment plan was then created to provide a framework to realise the opportunities and to align them to our strategic objectives. Flexibility in learning spaces is key to this plan and relies heavily on built pedagogy (Monahan, 2002). The aim was to provide staff with the skills, experience and support for the opening of the new Belfast campus in 2022 as well as enhancing practice on the other two campuses in Coleraine and Derry/Londonderry. It was also key for our students to be involved and for their voices to be heard, along with opportunities for collaborative partnership. As a result, a number of projects were created to help achieve the learning environment plan. These were:

- Introduction of Staff Active Learning Champions – One per school

- Introduction of Student Learning Partners – Current students x30

- Apps for Active Learning – Development of several classroom enhancement technologies

- Refurbishment of 20 legacy teaching spaces to active/collaborative design

- Creation of the Learning Lab – A safe space for staff to experiment

- Sequencing Learning Activities Pilot – Evaluating teaching practice in active learning spaces (Formal/informal and physical/digital)

How could others implement this idea?

Institutional change won’t happen overnight. Ulster University’s journey started back in 2015 and it is only now beginning to be realised, but it is still a work-in-progress. The Covid-19 pandemic did put a spanner in the works to a large extent as staff and students weren’t able to be on campus to explore the physical learning environments. However, there is a silver lining in that flipped learning (Advance HE, 2017) may have been a positive by-product of the online pivot. This does however raise a question around ensuring accessibility and universal design for learning (CAST, 2018) which are potential future additions to the learning environment plan. In 2017 when designing the learning environment plan, I identified the key objectives for this project that were aligned to our strategic plan (Ulster University, 2016) and the learning and teaching strategy (Hazlett, 2018). The key learning points from that exercise are listed below and available in a downloadable checklist (those in academic development roles may find it useful to formulate a plan for change):

- Look at your context. What is active learning within your institution? What are the basics of active learning to get staff started? And how can you make your staff and students aware of these?

- Identify the key operational objectives aligned to strategic priorities.

- What is within your sphere of influence and where do you need buy in and support from others?

- Who do you need to speak to, to make things happen? Start conversations with the Student Union, Timetabling, IT, Academic Development and Estates departments.

- Set out your timeframe with key delivery times. Make sure they are realistic.

- Start small. Scale up year on year.

- How can I get people onboard? Remember it’s all about people, so whether that is teaching staff, students or professional support staff we need people to enact change and become change agents. We wanted to reward students and staff for embracing active learning through:

- Active learning Champions (One per school) to reward staff for taking risks. The CMALT carrot was used to entice them to take on the role. At time of print 20 academic colleagues are registered for CMALT and 2 have already achieved certification.

- Student Learning Partners to reward students for partnership. Learning and teaching bursaries for 6 hours per week partnership activity.

- Pilot activity around using different Apps and spaces can give you an evidence base to demonstrate impact to senior management.

- Some things will be out of your control. Go with the flow.

- Schedule CPD sessions to encourage learning design that incorporates active learning.

- Include active learning pedagogies in revalidation/review activity. Constructive alignment is at the core of our curriculum design principles.

- Try and get the default room layout to be of an active/collaborative nature, where tables are set out in groups rather than in rows.

- Reflect on lessons learned from the online pivot. What can be kept?

Transferability to different contexts

Although this case study is within an HE context, the holistic approach is transferable to any sector. Simple things like adopting an active/collaborative approach to room layouts, with groupings rather than rows, can have a huge impact on the learning experience. In saying that, for a root and branch approach, there needs to be buy-in from senior management. Active learning needs to be embedded within institutional strategies and policies to help drive through the change at an operational level. This needs to be supplemented with a bottom-up approach, with student and staff champions acting as change agents.

Links to tools and resources

- Learning environment plan and active learning resources

- Institutional approach to active learning: lessons learned checklist

- Student Learning Partners

- Staff Active Learning Champions

- The Learning Lab

View resources on Padlet: https://padlet.com/rtg_beggs/u5adz7qzsfud4u95

References

Advance HE. (2017). Flipped learning – Knowledge hub. Advance HE. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/flipped-learning-0

Blake, I., & Bush, C. (2009). Project managing change: Practical tools and techniques to make change happen. Pearson Education.

Boys, J. (2017). Learning futures? Learning landscapes evaluation and recommendations. https://padlet-uploads.storage.googleapis.com/57779451/7b8e92508e701813936141ba95145128/UU_LLtransitions_Aug17FINAL_JosBoys.pdf

Beggs, R. T. G. (2019). Learning landscape activity. https://www.ulster.ac.uk/cherp/resources/learning-landscape-resources

CAST (2018). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 2.2. http://udlguidelines.cast.org

Hazlett, D. (2018). (Draft) Ulster University learning and Teaching strategy: ‘Learning for success’, 2018/19-2023/24. Ulster University. https://www.ulster.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/346791/Draft-LT-strategy-260618.pdf

Monahan, T. (2002). Flexible space & built pedagogy: Emerging IT embodiments. Inventio, 4(1): 1-19. http://publicsurveillance.com/papers/built_pedagogy.pdf

Nottingham Trent University. (2019). Active Collaborative Learning: Addressing barriers to student success: Final Report. https://www.ntu.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0027/1063089/NTU-ABSS-Final-Report-revised-Oct-2019.pdf

Ulster University. (2016). Five & fifty. https://www.ulster.ac.uk/fiveandfifty/strategicplan.pdf

Ulster University. (2020). Enhanced Belfast campus. https://www.ulster.ac.uk/campuses/gbd/about

Image Attribution

Figure 1. Ulster University Learning Environment Plan by Richard Beggs is used under CC-BY 4.0 Licence