Rubrics as active learning tools

Dr Paula Cardoso

What is the idea?

Rubrics are traditionally considered as assessment tools that facilitate the learning assessment process, both for teachers and students. However, more than helping promote an assessment tool for authentic learning, it can be one of the main active learning tools. Students will not only read the assessment rubrics pre-created by teachers, but they are invited to collaboratively create it, thus becoming even more engaged with their learning process right from the beginning. This idea will explain, step by step, how to successfully involve students into rubric building and reflect on their future learning, instead of only reflecting on their previous work.

Why this idea?

Active learning research is unanimous in stating that students benefit from becoming active participants and their learning increases when they have agency in building their own learning process.

Traditionally, rubrics are seen as tools capable of measuring and communicating student performance, based on previously defined criteria, that are described across a continuum of performance levels. According to Andrade (2010) and Jonsson (2014), they have been considered helpful because they are explicit regarding what is expected from students’ learning and, by doing this, they support student agency and self-regulation. Since students know in advance the defined performance criteria and levels, rubrics have an essentially formative role when directed to the assessment process. However, rubrics are not only assessment tools; they also represent one of the learning strategies with the greatest potential, as they allow students to build a learning path using the matrix of indicators and respective performance quality criteria as guidance maps. That is, instead of students getting feedback on their learning, they get feed-forward, a useful strategy to guide them towards future learning

In the context of emergency remote teaching, it became even more vital to define strategies that would promote students’ self-regulation of learning, allowing them to simultaneously become more autonomous and closely followed.

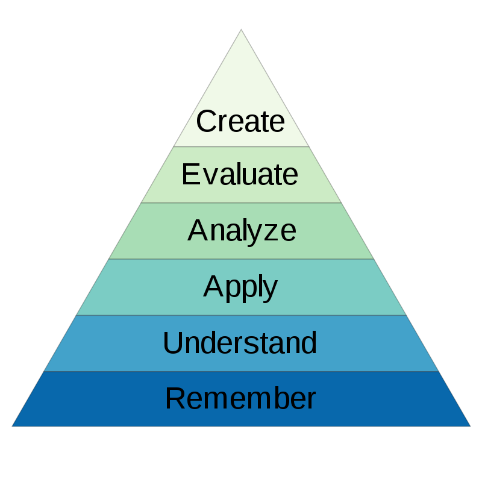

The revision of Bloom’s taxonomy (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001) is essential for us to better understand the advantages of this methodology, as it alludes to the increasing sequence of the complexity of cognitive processes.

Traditional learning usually involves basic cognitive processes that students need to mobilise, namely to ‘remember’, ‘understand’ and ‘apply’, whereas most complex processes (‘analyse’, ‘evaluate’ and ‘create’) are often associated with autonomous work. Thus, co-creating rubrics puts students in the most complex cognitive stage and therefore helps teachers support students in developing more elaborate skills, which is paramount in the context of active learning.

How could others implement this idea?

So, how can rubrics be used as learning tools, where students co-create the criteria and performance standards that they will be asked to develop?

Creating rubrics can be a very time-consuming task and it implies mastering a conceptual framework that students may find it difficult to grasp. Therefore, regardless of the type of rubric or type of work being defined through the rubric, defining a series of steps is crucial for the success of this task.

There are many online tools that have predefined matrices of rubrics and may be easily adapted to the learning goals and strategies of each discipline/subject.

One of them is Rubric Maker (https://rubric-maker.com/) which is quite intuitive and user-friendly.

Steps:

- Present and explain the methodology and analyse examples of rubrics together with students;

- Present the module/programme topics to students;

- Introduce the learning outcomes of the module/programme;

- Divide students into small groups and ask them to analyse the topics and corresponding learning outcomes and create the following: 1) assessment tasks; 2) criteria and performance standards for each assessment task;

- Ask each group to present their results;

- Collaborate as a whole group in negotiating and building a final rubric.

All steps are important, but this final step has a huge potential for students to actively reflect on different learning preferences and on their individual path towards performance standards that are actually meaningful for them. These are essential steps in building a student-centred environment, where students have the opportunity to step outside their comfort zone and to really engage into active learning.

Transferability to different contexts

This methodology can be transversally applied to all disciplines and contexts. However, it needs to be carefully planned and adapted to the learning goals and tasks that are specific to each discipline and/or subject.

It is also important to reinforce the fact that both the tasks and criteria need to be relevant and meaningful for students and need also be aligned with the learning outcomes.

References

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. Longman.

Andrade, H. L. (2010). Students as the definitive source of formative assessment: Academic self-assessment and the self-regulation of learning. In H. L Andrade & G. J. Cizek (Eds.), Handbook of formative assessment, (pp. 90–105). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203874851

Jonsson, A. (2014). Rubrics as a way of providing transparency in assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 39(7), 840-852. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2013.875117

Image Attributions

Girl with paint by Senjuti Kundn is used under Unsplash licence

Figure 1. Bloom’s Taxonomy Revised by Nicoguara is used under CC-BY 4.0 Licence