Story Game-Based Learning

Tab Betts

What is the idea?

This chapter will introduce the idea of Story Game-Based Learning (SGBL). The approach starts from a fanciful question: What if academic courses were designed as story-based games? This leads on to a more serious educational question: Is it possible to improve the learning experience by using story and game elements as tools to enhance the course content and learning design? In trying to answer this second question, Malone and Lepper’s theory of intrinsically motivating instruction (Malone, 1980, 1981; Malone & Lepper, 2021) suggested three components which should be incorporated to enhance learning design:

- A problem-solving challenge with an uncertain outcome, where the challenge-skill balance is adjusted on an ongoing basis to meet the needs of your individual learners (challenge)

- An aesthetically pleasing sensory experience, using mystery and gradual revealing of knowledge to stimulate aesthetic and intellectual curiosity (curiosity)

- A shared narrative or problem-solving scenario within which the learning is contextualised (fantasy)

This chapter will explore how these elements can be incorporated into the key stages of the learning process using story-game design, assessment and activities.

Why this idea?

There is a growing argument that stories and games are invaluable tools for motivating learners (e.g. Abbott, 2018; Squire et al., 2008; Williams et al., 1999; Zhang & Shang, 2015). With the success of video games to capture the imagination of society and the way in which visual storytelling platforms such as Netflix and YouTube have enthralled the public consciousness, these communicative modes clearly have something to teach us about engagement. In recent years, a wide range of research has emerged which supports the idea of game-based learning and storytelling in education (e.g. Abbott, 2018; Bitskinashvili, 2018; Malone & Lepper, 2021; Sidhu & Carter, 2021; Sidhu et al., 2021; Zhang & Shang, 2015).

How could others implement this idea?

Games and storytelling can be incorporated into almost every stage of the learning process. You may wish to start by experimenting with one or two of these, rather than trying to adopt them all in one go.

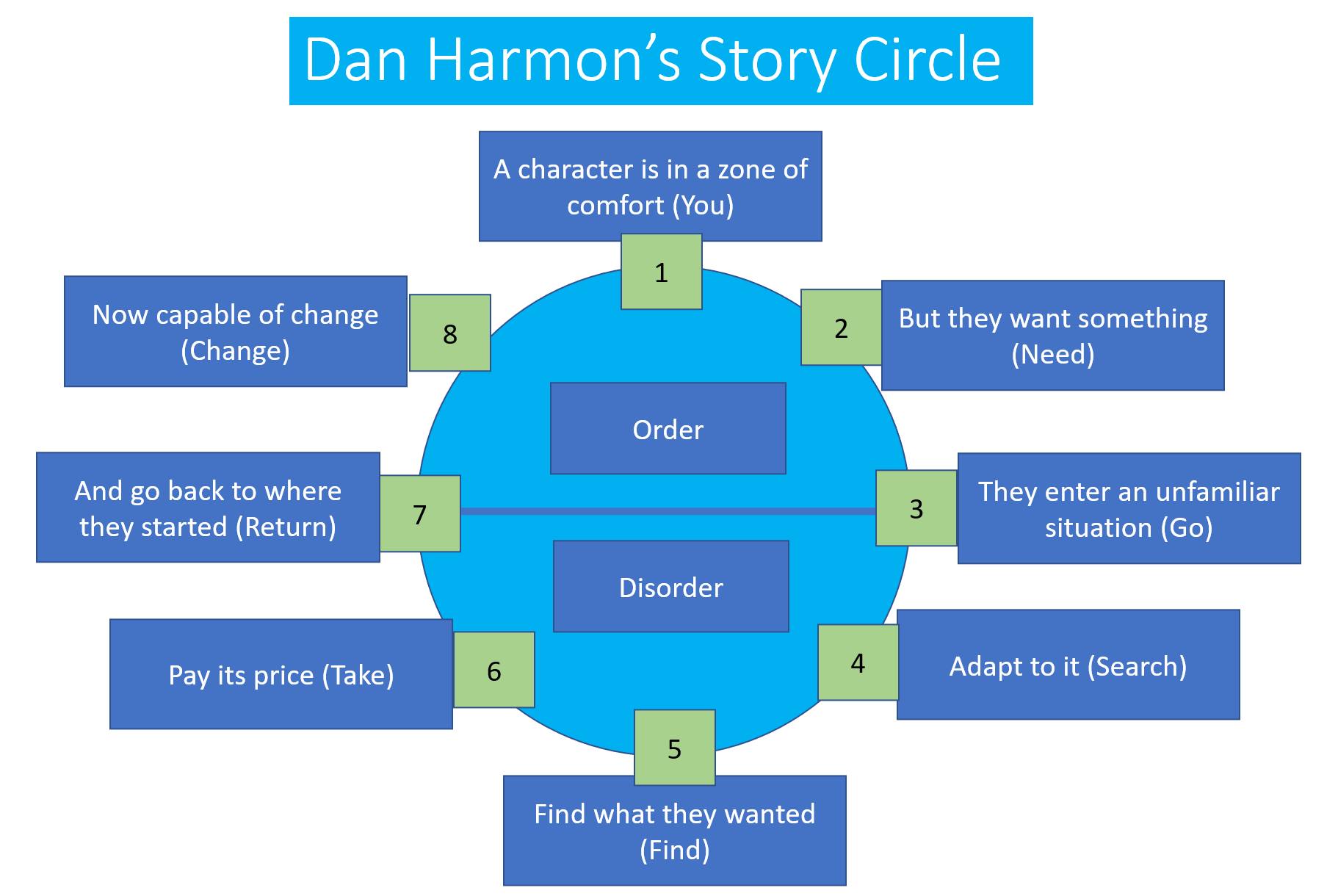

Story-game design – The principles of Story Game-Based Learning could be used to revise the overall design of the programme or module. This links closely to Malone and Lepper’s (2021) ideas of challenge, curiosity and fantasy, but also constructive alignment (Biggs, 1996; Biggs & Tang, 2011) and scenario-based learning (e.g. Errington, 2005; Smith, Warnes & Vanhoestenberghe, 2018). The first step is to choose an immersive story setting – a scenario, a setting, a protagonist, a goal, obstacles to achieving that goal, etc – which can map onto the existing intended learning outcomes (ILOs), assessment tasks (ATs) and teaching activities. For example, if you are teaching a module on computational linguistics, you could use a story about a young PhD student (protagonist) who wants to uncover the truth about an incorrect ruling in a murder case, by using their skills in forensic linguistics to investigate a database of court case transcripts (goal), but they are working as a research assistant for a well-established professor who, for some unknown reason, is trying to cover up this case and divert the PhD student’s efforts towards an unrelated research topic (obstacle). Learning design could be based on established models of storytelling, such as Joseph Campbell’s The Hero’s Journey, Maureen Murdock’s The Heroine’s Journey or Dan Harmon’s Story Circle (see Figure 2 below).

Story-game assessment – In Story Game-Based Learning, the assessment of the programme or module should link to the ILOs and immersive story setting, so that the learner’s goals are intentionally aligned with the goals of the protagonist. For example, in a film studies module about film noir, I created an assessment where learners acted as a detective to assemble a portfolio of evidence based on a murder case from the film they were studying. This evidence was discovered through exploring a choose-your-own-adventure webquest that I constructed and learners’ own self-directed research. Assembling this evidence required them to achieve the learning outcomes along the way, whilst helping the protagonist to achieve their goal of solving the murder case.

Story-game activities – One key component of Story Game-Based Learning is small group activities (with 2-6 learners per group) called story-games, in which learners engage in collaborative storytelling to explore scenarios and solve problems aligned to the ILOs and the topic they are studying. This draws on Malone and Lepper’s (2021) ideas of fantasy, challenge and curiosity, but also the use of roleplay and drama in education, and mechanics from tabletop games, such as The Ground Itself, Call of Cthulu and Dungeons & Dragons (Abbott, 2018; Daniau, 2016; Lean et al., 2018; Sidhu & Carter, 2021; Sidhu et al., 2021). In these tasks, learners ‘play’ together for a fixed amount of time and take on different roles.

Learners start with a scenario based on a real-life situation related to the topic of study. One or more of the learners will take on the role of Storyteller-Troublemaker, while the remaining learners act as Character-Problem-Solvers who each control the actions of one of the characters in the story-game. The Storyteller-Troublemaker’s responsibility is to set the scene of the scenario and provide the other learners with a problem for their characters to solve, adding new problems each time the story evolves as a result of decisions the Character-Problem-Solvers have made. Maintaining the level of challenge is key. The Storyteller-Troublemaker controls this by responding to the actions of the Character-Problem-Solvers within the story world, adjusting the problem/challenge and level of difficulty in order to keep them engaged. Success or failure in tasks is decided by the Storyteller-Troublemaker, based on application of knowledge/skill (their assessment of the decisions and solutions suggested by the group), as well as elements of luck (e.g. dice, spinners, cards, random numbers generators, etc) introduced to randomise certain outcomes within the scenario, such the Character-Problem-Solvers trying to perform a particular action or take a risk within the story world.

After the story-game, the group engages in peer reflection and assessment, summarising their learning and identifying strengths and areas for development in their approach to the scenario (captured via an online survey or collaborative document). They then rejoin the whole class to share findings, either feeding back verbally or simultaneously writing their reflections in a shared space (e.g. a Padlet wall, collaborative document or collaborative whiteboard). At this stage, learners can ask any unanswered questions which arose during the process, then make suggestions/predictions about how the scenario should evolve in the next episode of the story. Finally, the class reviews the extent to which the ILOs were achieved and summarises key takeaways.

Transferability to different contexts

Story Game-Based Learning could be adapted to a variety of different disciplines and learning contexts. The key would be in choosing the right stories and scenarios, adjusting the level of challenge and tailoring aesthetic and intellectual curiosity to fit the needs of your individual learners. Because of this, it may be useful to begin by consulting the learners about what kind of stories and/or games would help them to understand and relate to the subject content.

Links to tools and resources

- The Ground Itself: https://everestpipkin.itch.io/the-ground-itself

- Call of Cthulu: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Call_of_Cthulhu_(role-playing_game)

- Dungeons & Dragons: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dungeons_%26_Dragons

- Joseph Campbell’s The Hero’s Journey: https://orias.berkeley.edu/resources-teachers/monomyth-heros-journey-project

- Maureen Murdock’s The Heroine’s Journey: https://libguides.gvsu.edu/c.php?g=948085&p=6857313

- Dan Harmon’s Story Structure Circle: https://www.nfi.edu/story-circle/

References

Abbott, D. (2019). Modding Tabletop Games for Education. In: Gentile, M., Allegra, M., Söbke, H. (eds) Games and Learning Alliance. GALA 2018. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 11385. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11548-7_30

Biggs, J. (1996). Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. Higher Education, 32(3), 347-364. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00138871

Biggs, J., & Tang, C. (2011). Teaching for quality learning at university: What the student does (4th ed.). Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press.

Bitskinashvili, N. (2018). Integration of education technologies (digital storytelling) and sociocultural learning to enhance active learning in higher education. Journal of Education in Black Sea Region, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.31578/jebs.v3i2.136

Errington, E. (2005). Creating learning scenarios: A planning guide for adult educators. Cool Books New Zealand.

Daniau, S. (2016). The transformative potential of role-playing games—: From play skills to human skills. Simulation & Gaming, 47(4), 423-444. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878116650765

Lean, J., Illingworth, S., & Wake, P. (2018). Unhappy families: using tabletop games as a technology to understand play in education. Research in Learning Technology, 26. https://doi.org/10.25304/rlt.v26.2027

Malone, T. W. (1980, September). What makes things fun to learn? Heuristics for designing instructional computer games. In Proceedings of the 3rd ACM SIGSMALL symposium and the first SIGPC symposium on Small systems (pp. 162-169). https://doi.org/10.1145/800088.802839

Malone, T. W. (1981). Toward a theory of intrinsically motivating instruction. Cognitive science, 5(4), 333-369. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15516709cog0504_2

Malone, T. W., & Lepper, M. R. (2021). Making learning fun: A taxonomy of intrinsic motivations for learning. In R. E. Snow & M. J. Farr (Eds.), Aptitude, learning, and instruction (pp. 223-254). Routledge.

Smith, M., Warnes, S., & Vanhoestenberghe, A. (2018). Scenario-based learning. In: J. P. Davies & N. Pachler (Eds.), Teaching and learning in higher education: Perspectives from UCL (pp. 144-156). UCL IOE Press.

Sidhu, P., & Carter, M. (2021). Exploring the resurgence and educative potential of ‘dungeons and dragons’. Scan: The Journal for Educators, 40(6), 12-16. https://doi.org/10.1177/15554120211005231

Sidhu, P., Carter, M., & Curwood, J. S. (2021). Unlearning in games: Deconstructing failure in Dungeons & Dragons. Proceedings of DiGRA Australia, 1-4.

Squire, K. D., DeVane, B., & Durga, S. (2008). Designing centers of expertise for academic learning through video games. Theory into Practice, 47(3), 240-251. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405840802153973

Williams, K. C., Cooney, M., & Nelson, J. (1999). Storytelling and storyacting as an active learning strategy. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 20(3), 347-352. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163638990200312

Zhang, L., & Shang, J. (2015, July). How video games enhance learning: A discussion of James Paul Gee’s views in his book what video games have to teach us about learning and literacy. In International Conference on Hybrid Learning and Continuing Education (pp. 404-411). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20621-9_34

Image attribution

Fantasy book image by Tumisu on Pixabay