Block ‘n’ flip: boosting student engagement in the HE classroom

Nicoletta Di Ciolla; Dr Chrissi Nerantzi; and Dr Gerasimos Chatzidamianos

What is the idea?

Actively and pro-actively involving students in their learning, providing them with a supportive environment, is key to student empowerment, autonomous learning and development.

One of Manchester Metropolitan University’s (ManMet) core strategies to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on the student experience, to which engagement is a core contributor, was to configure learning and teaching into “blocks”. Thus, the academic year was divided into four six-week teaching blocks, each occupied by 30 credits worth of content, and followed by one assessment week (Nerantzi & Chatzidamianos, 2020; Nerantzi et al., 2021). Academics worried that, by condensing and intensifying learning, teaching and assessment, this structure would cause insurmountable difficulties: the challenges seemed more daunting than the opportunities were exciting. The inevitable re-think of teaching and learning approaches searched for alternative pedagogical practices that would secure students’ engagement and success despite learning being operationalised remotely (and in isolation) and intensively. The main questions were: how could we ensure that students stayed on the course, remained engaged and participative? What alternative to the traditional campus-based provision could we offer that would be equally effective, or better still deliver additional, unexpected benefits?

The authors’ idea was to adopt peer- assisted, flipped learning, approaches that encouraged active learning, that could help create a seamless learning experience within and beyond the physical and virtual classroom, and at the same time remove some of the problems created by the block delivery (Nerantzi, 2020). We called this approach Block ‘n’ Flip.

Keeping in mind that our objectives were to:

- deliver depth and breadth (subject content) and develop higher order critical thinking skills in far less time than usual; and

- enable students to become autonomous learners,

- we redesigned our units to:

- make interaction an integral part of the Teaching & Learning (T&L) philosophy;

- distribute learning activities across the pre-, during and post-class stages (Ehlers, 2020; Scott, 2020), exploiting the potential of technology to make this happen;

- promote active blended learning; and

- align all learning activities and assessment constructively with the learning outcomes.

This approach enabled us to reduce reliance on teaching as telling (i.e. to move away from teaching events where student participation mostly implies mechanical note-taking, with minimum active engagement) and to use class time for scaffolded learning activities instead. Flipped learning and peer assisted learning strategies with synchronous and asynchronous learning opportunities were key to achieving our objectives.

The following pages illustrate how the above plan was put into practice by one of the authors in one of her modules.

‘FLIPPING LATIN’

The principles of the flipped classroom had been piloted in a Beginners Latin class just before COVID struck: the tutor had selected several ‘knowledge clips’ that covered a range of topics relevant to the unit (recorded in-house or found in YouTube) for students to watch asynchronously. To make the viewing activity interactive, a video tagging software was used: a tool – called EVOLI – developed within the EU funded project ELSE of which ManMet was a partner (cf.https://www.evoli.polimi.it/ or https://evoli.altervista.org/. User instructions can be found in Appendix 2).

As the EVOLI tool specifically required students to respond to a clip content by inserting comments or indicating the extent to which they understood and/or wanted further explanation on the topic, its consistent use made engagement and class interaction a distinctive feature of the course (Nerantzi et al., 2021a).

The group of 24 students in the class consisted mostly of 1st year Ancient History undergraduates, plus a handful of MA Ancient History students (3) and one PhD candidate. The students were all Anglophone – so Latin, with its limited contiguity with English, was a bit of a mystery to most. There were widespread confidence issues – especially fresher anxiety about tackling new content unaided – and no established group cohesion, as the students were new to the university.

Given the group composition, plus the compressed nature of the experience due to the reduced teaching time, the following were important, despite a significant level of trepidation from the tutor about asking students to ‘go solo’ for the initial part of the learning:

1. opportunities for all students to learn core concepts, and at their own pace;

2. flexible (= personalised) scaffolding for the live session; and

3. efficient use of class time (e.g., less time spent introducing core concepts, more time to discuss them and consolidate understanding).

The approach and its rationale were explained to the students at the outset:

- independent work had to be carried out in advance of the live session and it was a fundamental part of the experience; and

- the chosen learning approach would be greatly beneficial to them (= they would learn more and more easily) and was ‘energy efficient’ (= having zero impact on their overall workload).

The preparatory work set was:

- Multimodal – the videoclips were accompanied by a range of other written or visual resources for students to explore. Variety was important.

- Participatory – students were encouraged to collaborate with each other, through sharing resources and distributing tasks amongst themselves; and

- Useful – for the tutor (who was able to customise the follow up “live” sessions, which were targeted to that group and its needs); for the students (who could participate in the construction of the unit, orienting they choice of authors, or topics).

The experiment was a success (in terms of student engagement, satisfaction and results), and the pilot experience highlighted the areas that could be improved (See Appendix 1 for a specific application).

Transferability to different contexts

The COVID emergency made many colleagues eager to try their hand at flipped learning and peer assisted learning, and the experience of Latin demonstrated how overturning the traditional order of teaching and learning and making digital technology an integral part of the delivery of the unit can work across disciplines.

From the ‘technical’ side, the requirements are:

- A series of short knowledge clips (no more than 5-7 minutes long) that explore core concepts – these can be produced by the tutor, reworked on the basis of what would have been covered in class, or can be found on the web, where plenty of material is available across subjects; and

- A range of linked activities that students complete ahead of the live sessions. Activities can be intercalated (watch for 2 minutes, then complete a task, then resume the viewing) or done before or after the viewing.

The preconditions are few, but indispensable to the success of the approach:

- The preparatory work must be designed as an integral part of the T&L- not an optional activity. Students will take responsibility for their independent learning.

- All additional activities should test knowledge and provide more opportunities for learning – the Latin flipped class on relative clauses stimulated reflections about communication strategies that conceal or reveal information, remove or add ambiguity.

- All activities should be able to “travel beyond the unit” and contribute to the students’ self-concordance – covering topics that resonate as much as possible with students’ developing interests and values, and that can be seen as relevant to their lives and future ambitions. The Latin sessions offered illuminating insights into contemporary society and culture.

- Activities must be relevant to the assessment, and the assessment should itself be a form of learning – encouraging students to form study partnerships, to work together to make sense of new information, and to contribute their respective prior knowledge to help their peers with new learning.

- Students must be made to feel that they are not alone – the tutor is there, and help is at hand.

- Conditions must be made equitable – digital poverty, time poverty and differing digital capabilities must be considered, so that no one is excluded from the full learning experience.

Links to tools and resources

Di Ciolla, N., Chatzidamianos, G., Nerantzi, C., Parry, A. Patil, S., & Sashikumar, S. (2021) Block ‘n’ Flip. Boosting student engagement in the HE classroom in “Coronial” times [invited]. 6th Annual Flipped Learning Conference Post COVID 19: Evolution of the Classroom. University of Northern Colorado, 3-4 June 2021. https://mmutube.mmu.ac.uk/media/Kaltura+Capture+recording+-+May+24th+2021%2C+12A02A56+pm/1_x4kd9v2j

EVOLI, a video tagging tool developed by the ELSE Erasmus plus project team: https://www.evoli.polimi.it/

References

Ehlers, U-D. (2020) Future Skills. The future of learning and higher education, translated by Ulf-Daniel Ehlers, Patricia Bonaudo, Laura Eigbrecht Karlsruhe, Future Higher Education, Wiesbaden: Springer VS, pp 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-29297-3_1

Nerantzi, C. (2020) The use of peer instruction and flipped learning to support flexible blended learning during and after the COVID-19 Pandemic, International Journal of Management and Applied Research, 7(2), 184-195. https://doi.org/10.18646/2056.72.20-013

Nerantzi, C., Chatzidamianos, G., & Di Ciolla, N. (Eds.) (2021) Moving to block teaching: challenges and opportunities. Learning and Teaching in Action [special issue], 14(1). https://www.celt.mmu.ac.uk/ltia/

Nerantzi, C., Chatzidamianos, G. and Di Ciolla, N. (2021a) Reflections on block teaching, three practitioners, three voices. In C. Nerantzi, G. Chatzidamianos & N. Di Ciolla (Eds.). Moving to block teaching: Challenges and opportunities. Learning and Teaching in Action, 14(1), 18-34. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6645367

Nerantzi, C., & Chatzidamianos, G. (2020). Moving to block teaching during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Management and Applied Research, 7(4), pp.482-495. https://doi.org/10.18646/2056.74.20-034

Scott, G. (2020), Can we plan for a socially distanced campus?, WonkHE, [Online] available at: https://wonkhe.com/blogs/can-we-plan-for-a-socially-distanced-campus/

Image attribution

Watering mind image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay

Appendices

Appendix 1

THE FOX AND THE GRAPES AND THE THORNY ISSUE OF RELATIVE PRONOUNS

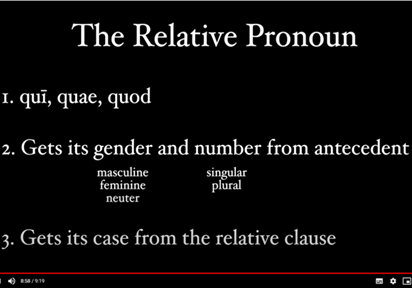

Figure 1. Screenshot of YouTube Video on The Relative Pronoun by Latintutorial is used under CC-BY 4.0 Licence

We were reading an extract from De vulpe et uva, a famous tale narrated in Latin by Phaedrus, where a few instances of relative pronouns occurred. I observed that:

- all students understood the gist of the story and were able to translate it, but had a limited understanding of the function and meaning of those “words” (i.e. the relative pronouns) in the Latin context.

- many students found the concept of “relative pronoun” complex, even when referred to English and illustrated through examples from English.

In preparation for the following week – and for more reading about Roman wisdom – students were asked to watch a 9 minute ‘knowledge clip’ on relative pronouns in Latin.

HOW IT WORKED: I made the clip available through EVOLI, requiring students to interact with the video – tag it as they watched it, indicating the points where they ‘get it’, where they ‘don’t get it’, and entering any comments, observations or questions.

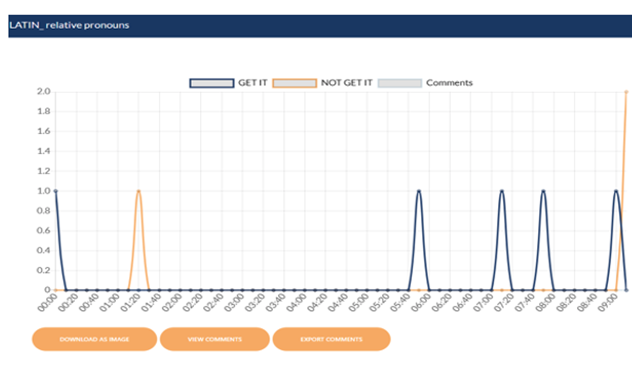

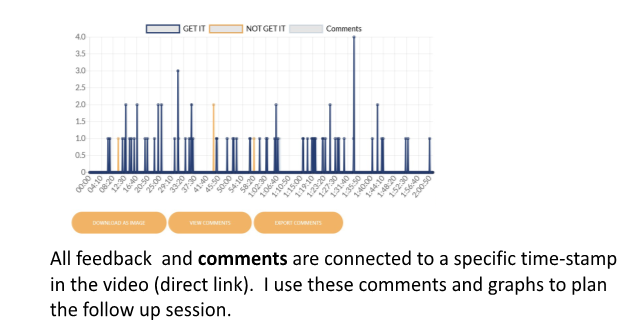

When I examined the summary of the students’ viewings – EVOLI provides a graph showing the exact time of the clip where each comment was raised – I noticed a peak of ‘I don’t get it’ in two specific points: minutes 1.2 and minute 9, which correspond to the introduction of the grammar explanation. This confirmed to me that students struggled to understand abstract concepts, and to apply deductive reasoning.

In particular, minute 9 corresponded to the grammar recap, which presupposed an understanding of the theoretical content of the entire video:

Figure 2. Screenshot of Evoli results on The Relative Pronoun by Nicoletta Di Ciolla is used under CC-BY 4.0 Licence

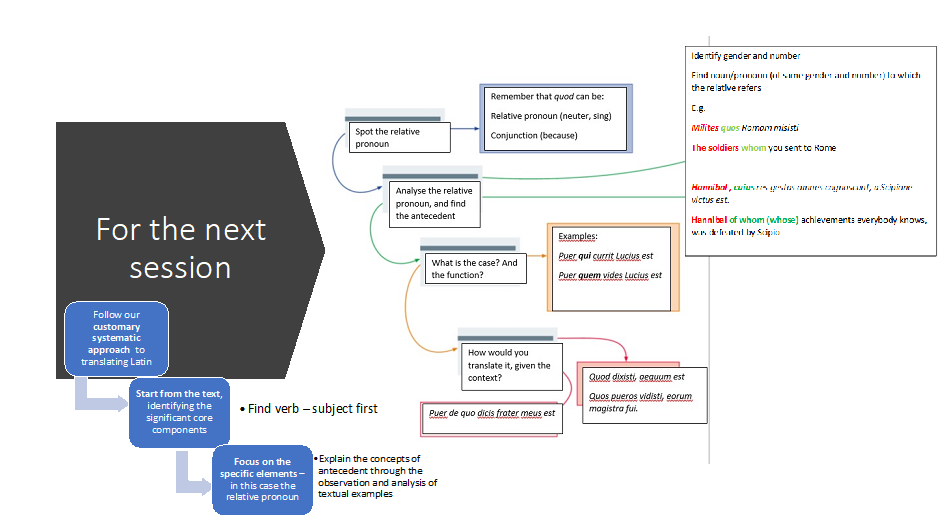

Aware of what the sticking points were (and conversely of what was likely to be plain sailing), I structured the follow-up live class as in the diagram below, which students received in advance, and which highlighted the steps we were going to take in the session:

Figure 3. Screenshot of Lesson Plan on The Relative Pronoun by Nicoletta Di Ciolla is used under CC-BY 4.0 Licence

SUMMARY:

a.We followed our customary approach to translating Latin – a method with which students were familiar and comfortable (left hand side of the table above);

b.We then focussed specifically on the relative pronouns, and practised locating the other elements of the sentence that clarified their function and meaning (=the antecedents);

c.We ‘played’ with changing pronouns (cases, genders, as appropriate) and observing the corresponding changes in the meaning of a sentence – students were quite intrigued by the ambiguity that can be generated by small grammar manipulations.

Point a. enabled me to structure the exercise in a format that was familiar to students, making their engagement easier and quicker; point b. helped students through text and grammar in a systematic, progressive, stepped manner; point c. stimulated confidence in manipulating the language, introducing an element of humour too, all conducive to learning.

Appendix 2

The video tagging tool EVOLI is downloadable from https://evoli.polimi.it/ or https://evoli.altervista.org/.

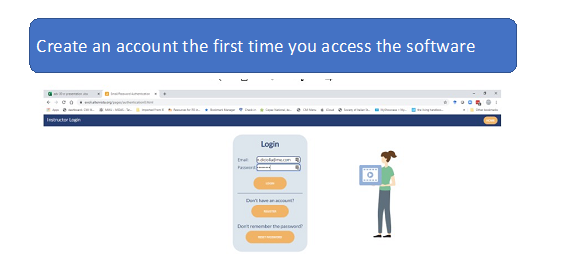

The first time the software is accessed, users need to create a personal account.

There are separate account areas – for tutors and for students.

(all figures below are screenshots from presentations done by Nicoletta Di Ciolla and used under CC-BY 4.0 Licence)

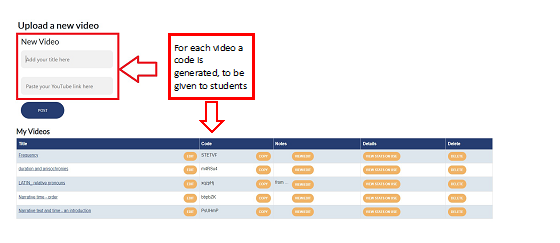

Videos can be uploaded onto EVOLI from YouTube. They can be given a new title (so that content and relevance are clear), and each upload generates an EVOLI code – which tutors give to students.

Students access their EVOLI account, enter the code provided by the tutor and watch the video.

While watching, they interact with the content by indicating what is clear, what is not clear, and any questions/comments they have.

Once they have finished the viewing activity, they submit their feedback.

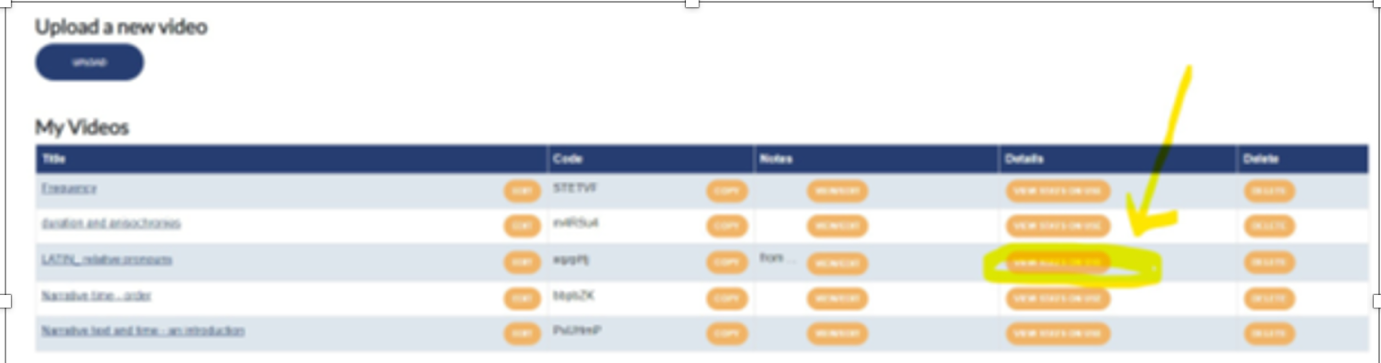

Analytics for the activities are provided in the tutor area – how many people have viewed the video, how many responses there have been, the parts that students found clear or difficult, and what comments have been posted.

A clear diagram shows what reactions have been left and at what points of the video.

These data can be used to plan the follow-up sessions.