Active learning about active-learning design with a ‘tool-to-think-with’

Dr Éric Bel and Johanna Tomczak

What is the idea?

What is the idea?

What would you do if, in the middle of a busy day, you arrived in a classroom, where a group of eager learners were waiting for you, and suddenly you discovered that there was a power cut? How would you react in relation to the digital technology-dependent learning session that you had thoroughly planned to facilitate on this occasion? Cancel this lesson, revert to talking to – or, worse, at – your audience, ready for a passive learning experience, or do your best, and decide that, next time, you will plan learning differently?

What follows is our contribution to prompting you, or those you support in enhancing their teaching, to review the way active-learning opportunities are planned, with the help of a simple, practical “tool to think with over a lifetime” (Papert, 1980, p. 76). At this stage, we should note that ‘active learning’, in our view, refers to any type of learning that will involve learners, therefore prompt them to engage in some form of activity; build upon learners’ intrinsic motivations, rather than extrinsic reasons, for learning; promote construction of knowledge and development of skills by, rather than transmission of information to, learners; allow, and encourage, them to explore and make mistakes; provide learners with comments on their progress.

We start from the premise that, in a time of crisis, when much of what we need in order to teach has broken down, there is nothing more useful than a good old, tested theoretical framework. This enables us to stop, reflect and, perhaps, go one or two steps back in our active-learning design practice, to anticipate what should remain, for example, if technology fails. We hope that you will be able to apply our printable easy-to-use ‘tool-to-think-with’ to designing active learning, to avoid some potential technological nightmare; or simply to remember why you used to enjoy learning and teaching so much before electronic devices became ubiquitous in education!

Our proposed tool-to-think-with emphasises the idea that, whether you plan to facilitate a single lesson, a series of connected learning sessions or a whole course, the best approach to adopt may well be to refrain from thinking about using the latest technological gimmicks. Indeed, instead, adopting a systematic approach to thinking about what is going to happen in the learning opportunities that you are designing should enable you to be as ready as possible for whatever crisis that is still to come, be it this power cut which was mentioned earlier, or any other types of critical incidents in your teaching practice.

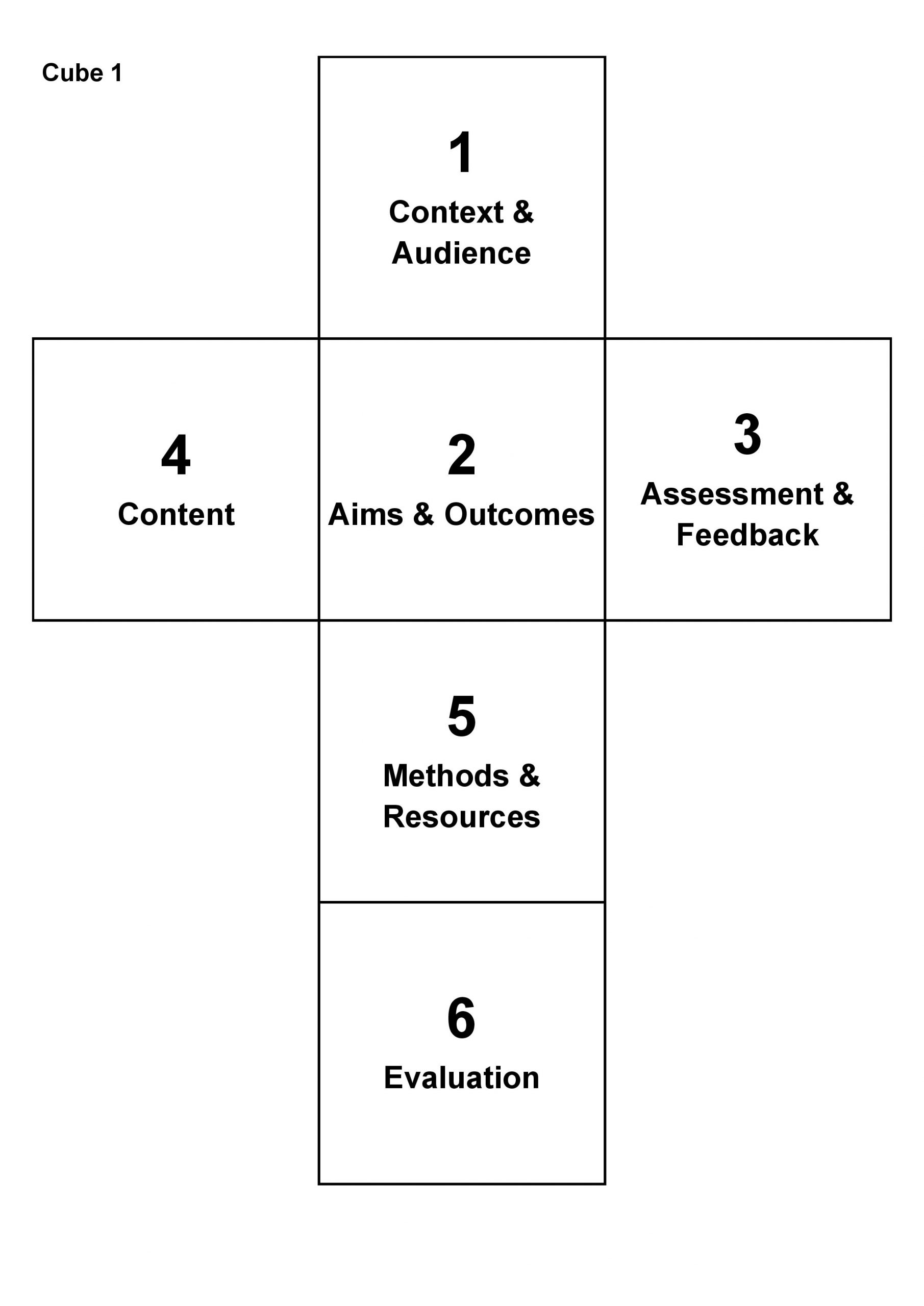

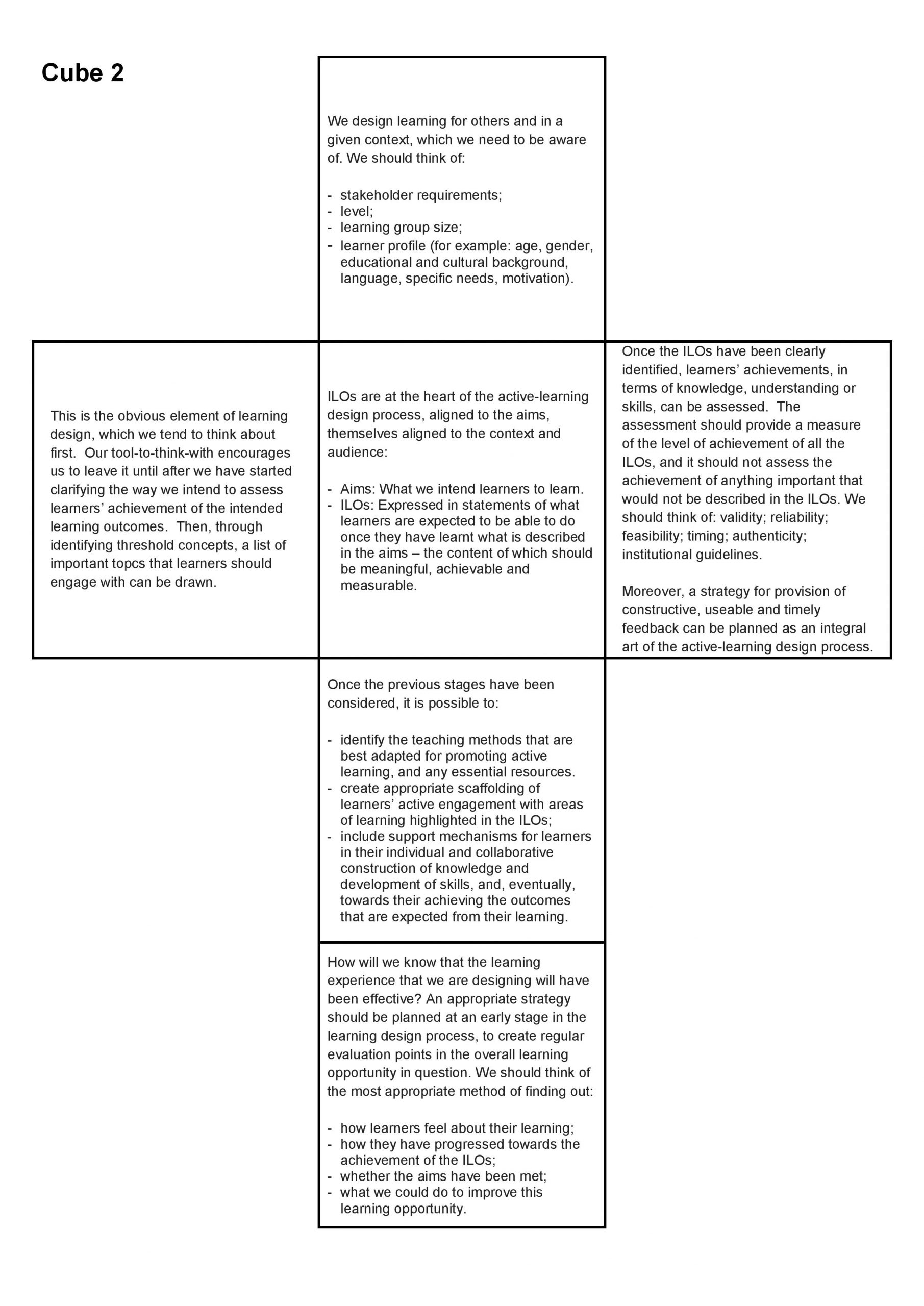

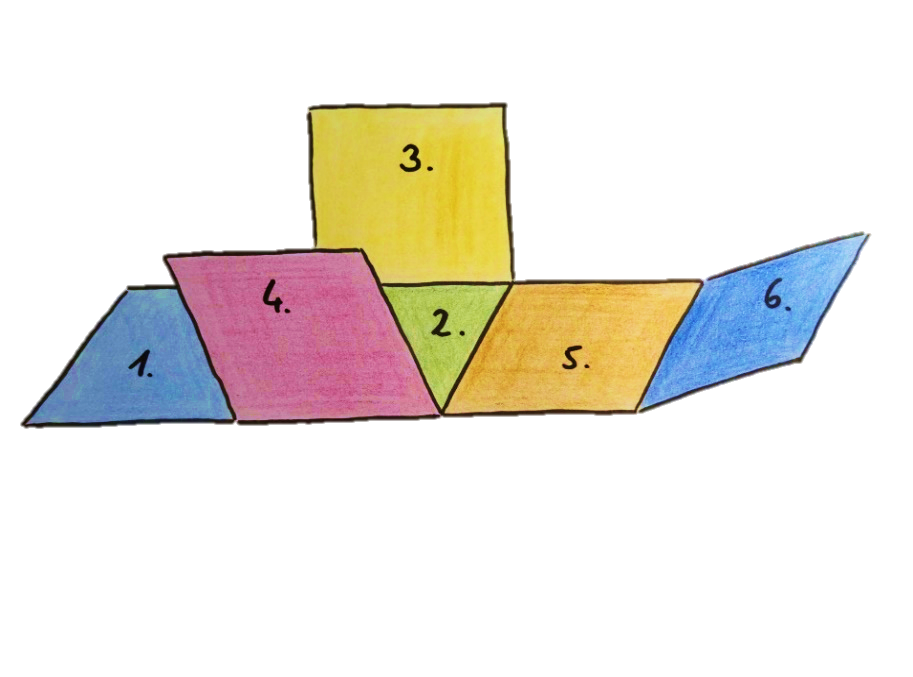

This is how we would like to share with you our idea of a tool-to-think-with, for active-learning design, which is largely based on a well-rehearsed, but powerful, concept: What Biggs (1996) calls ‘constructive alignment’ (see also Young’s and Perović’s (2014) suggested activities that could be implemented in individual lessons). Our tool-to-think-with consists of two cubes: one with, on each side, one number from 1 to 6, along with the title of one of the six stages of our recommended active-learning design process (Cube 1); the other one with, on each side, more detailed information on each of these stages (Cube 2).

The following table provides more detail about each cube (please note that templates are attached to this text). For both cubes, the sides are listed in chronological order of these six main active-learning design stages.

|

Cube 1 |

Cube 2 |

|

|

We design learning for others and in a given context, which we need to be aware of. We should think of: stakeholder requirements; level; learning group size; learner profile (for example: age, gender, educational and cultural background, language, specific needs, motivation). |

|

|

Intended learning outcomes (ILOs) are at the heart of the active-learning design process, aligned to the aims, themselves aligned to the context and audience: Aims: What we intend learners to learn. ILOs: Expressed in statements of what learners are expected to be able to do once they have learnt what is described in the aims – and the content of which should be meaningful, achievable and measurable. |

|

|

Once the intended learning outcomes (ILOs) have been clearly identified, learners’ achievements, in terms of knowledge, understanding or skills, can be assessed. The assessment should provide a measure of the level of achievement of all the ILOs, and it should not assess the achievement of anything important that would not be described in the learning-outcome statements. We should think of: validity; reliability; feasibility; timing; authenticity; institutional guidelines. Moreover, a strategy for provision of constructive, useable and timely feedback can be planned as an integral part of the active-learning design process.

|

|

|

This is the obvious element of learning design, which we tend to think about first. Well, our tool-to-think-with encourages us to leave it until after we have started clarifying the way we intend to assess learners’ achievement of the intended learning outcomes. Then, through identifying what Meyer et al. (2006) call ‘threshold concepts’, a list of important topics that learners should engage with can be drawn. |

|

|

Once the previous stages have been considered, it is possible to: identify the teaching methods that are best adapted for promoting active learning, as well as any resources – be they technological or not – that could be essential; create appropriate scaffolding (Bruner et al., 1976) of learners’ active engagement with areas of learning highlighted in the learning-outcome statements; include support mechanisms for learners in their individual and collaborative construction of knowledge and development of skills, and, eventually, towards their achieving the outcomes that are expected from their learning. |

|

|

How will we know that the learning experience that we are designing will have been effective? An appropriate strategy should be planned at an early stage in the learning design process, to create regular evaluation points in the overall learning opportunity in question. We should think of the most appropriate method of finding out: how learners feel about their learning; how they have progressed towards the achievement of the intended learning outcomes; whether the aims have been met; what we could do to improve this learning opportunity.

|

Why this idea?

As we, educators, often feel that we are asked to make changes just for the sake of changing, it is refreshing to be able to slow down, or even stop, and reconsider what really matters to us in our professional lives. In this day and age of digitally-heavy instruction, the tutor’s worst nightmare may look like the failure of this very technology. However, it should not have to be this way; if only, when we plan learning opportunities, we could go back to the fundamentals of the tutor’s facilitating role (see our interpretation of Laurillard’s (2002) conversational model in Tomczak & Bel, 2021, p. 4).

We are likely to have had an overdose of digital technology imposed upon us, lately, for example, during the pandemic of the early 2020s. This technocratic approach has helped for a while, but we would like to suggest that our tool-to-think-with could be used to bring back to the forefront of our thinking about teaching, the powerful process of active-learning design described above.

How could others implement this idea?

Well, our tool-to-think-with could form the active learning part of a workshop with teachers who are new to facilitating learning in higher education, for example postgraduate researchers. Workshop participants could be asked, first, to design, in pairs or small groups, a seminar based on a given topic and a digital presentation used in a related lecture. Then, they could be asked to explain their approach to designing this seminar. Their description of this process is likely to show that their focus is on content and deciding what to include on each slide of a digital presentation. At this stage of the workshop, the concept of constructive alignment, mentioned previously, could be introduced, and more specifically the main stages of the active-learning design process described above.

As workshop participants are given the task to apply their new learning to designing the same seminar, they could be prompted to utilise our tool-to-think-with. Initially, participants could be asked to consider Cube 1 and explain, in chronological order, what each stage of the active-learning design process is about. If they are uncertain about any of the six stages referred to on Cube 1, then they could be prompted to use Cube 2 and find the matching recommendations. This visual, kinaesthetic, as well as collaborative, experience promotes, and helps workshop participants to memorise, a structured and anticipatory approach to thinking about learning sessions that they are going to facilitate.

This type of active learning about active-learning design, with our tool-to-think-with, has been shown to lead to a paradigm shift regarding what active learning is about and how it can be planned into any learning opportunities.

Transferability to different contexts

As explained in this example, this tool-to-think-with can be used to help with planning individual learning sessions. However, the process of designing active learning is similar when planning modules or whole courses. Therefore, the tool-to-think-with can be used equally successfully, in those situations, with individuals or groups, to emphasise what, at the planning stage, really matters when designing active learning; especially when there might be a power cut!

Links to tools and resources

See Appendix for templates.

References

Biggs, J. (1996). Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. Higher Education, 32(3), 347-364. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00138871.

Bruner, J. S., Ross, G., & Wood, D. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines, 17(2), 89-100. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1976.tb00381.x.

Laurillard, D. (2002) Rethinking university teaching – A conversational framework for the effective use of learning technologies. Second edition. London: Routledge. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315012940.

Meyer, J. H. F., Land, R., & Davies, P. (2006). Implications of threshold concepts for course design and evaluation. In Meyer, J. H. F. & Land, R. (eds). Overcoming barriers to student understanding: Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge. London: Routledge, 195-206.

Papert, S. (1980). Mindstorms: Children, computers and powerful ideas. Basic Books.

Tomczak, J., & Bel, E. (2021). A conversational framework for learning design (in adverse times). Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education, (22). Available at: https://doi.org/10.47408/jldhe.vi22.705.

Young, C., & Perović, N. (2016). Rapid and Creative Course Design: As Easy as ABC? Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 228, 390-395. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.07.058.

Image Attributions

Open Cube by Eric Bel and Johanna Tomczak is used under CC-BY 4.0 Licence

Cube side 1. Content and Audience by Eric Bel and Johanna Tomczak is used under CC-BY 4.0 Licence

Cube side 2. Aims and Outcomes by Eric Bel and Johanna Tomczak is used under CC-BY 4.0 Licence

Cube side 3. Assessment and Feedback by Eric Bel and Johanna Tomczak is used under CC-BY 4.0 Licence

Cube side 4. Content by Eric Bel and Johanna Tomczak is used under CC-BY 4.0 Licence

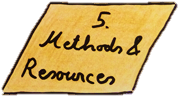

Cube side 5. Method and Resources by Eric Bel and Johanna Tomczak is used under CC-BY 4.0 Licence

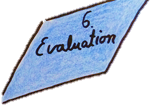

Cube side 6. Evaluation by Eric Bel and Johanna Tomczak is used under CC-BY 4.0 Licence

Template Cube 1 by Eric Bel and Johanna Tomczak is used under CC-BY 4.0 Licence

Template Cube 2 by Eric Bel and Johanna Tomczak is used under CC-BY 4.0 Licence

Appendix

Templates