Democratising teaching: student votes and module case studies

Dr Peter Finn

What is the idea?

Building on experience from two modules, this entry explores the process of allowing students to vote on module content. Though not applicable to all modules, or perhaps even all content on any module, this practice can, depending on the specifics of a module, allow students a say in material covered. Such votes can be used to decide content for a single session or group of sessions. Reflecting pre-existing literature, quantitative data and qualitative comments from Module Evaluation Questionnaires suggest students value the ability to feed into the selection of teaching content, as well as an explicitly emancipationary framing.

Why this idea?

Literature suggests that students and teachers who engage in shared decision making about what material is covered and how teaching is structured are more committed, with the added benefit that such shared decision making may also help develop interpersonal skills needed for navigating complex, and ever changing, social contexts (Lubicz-Nawrocka, 2018). Such engagement is often discussed with relation to terms such as co-creation and students as partners (Healey, Flint & Harrington, 2014). Building on a method utilised on two modules across numerous years, and the insight that the language used in shared decisions in teaching is important (Matthews, 2016), this chapter provides a toolkit to embed emancipationary political discourse and practice drawn from democratic processes into shared decision making processes aimed at allowing students to feed into module structure and content.

How could others implement this idea?

This idea can be implemented in various ways, both high and low tech.

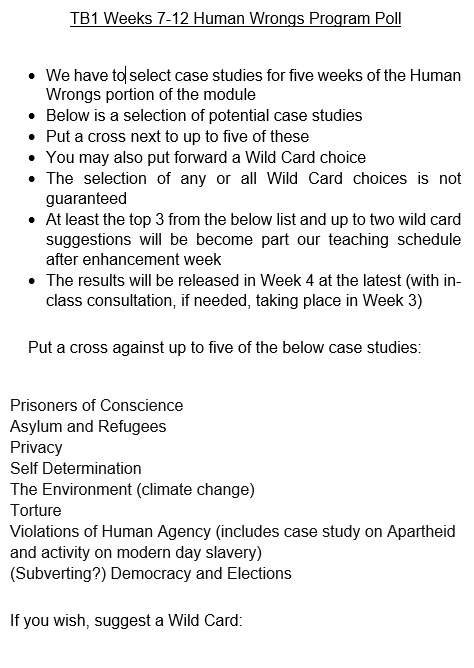

- Firstly, a teaching team need to decide how much teaching space on a module will be allocated to student votes: this could be anything from a single week to half a module or more. Different modules and teaching styles will suit different amounts. In the sample ballot below five weeks, occurring across six weeks, were allotted.

- Secondly, the choices on offer need to be determined. Will students, for instance, be given a predetermined list to choose a selection from? Will they be able to suggest case studies to choose from (which, as shown below, I call Wild Cards)? If Wild Cards are allowed, will there be a limit to the number included (I would suggest considering some limits here, with predetermined constraints highlighted prior to voting)? How will you determine which Wild Cards are implemented?

- Thirdly, the method used to allow students a choice in case study selection needs to be determined and communicated. Will you make a ballot sheet such as the one below, run a show of hands, leave the room and allow students to determine their own method of selection, or run an online poll?

- You need to think about how you feed results back. Will you do so in class (whether online or in person), via a module announcement, or a mixture of the two? Do you just provide the results or allow time to discuss the results (I would advise doing so, especially if you end up with a mixture of pre-suggested topics and Wild Cards)?

- Finally, you need to implement the chosen choices. Depending on the module this may involve some or all of the following; creating VLE pages: creating reading lists: generating lecture, seminar, and workshop materials: and developing assessment briefs.

A ballot used to select module material

There is no single way to carry out the above method. The specifics will depend on your own teaching style, those you are teaching with, and the module you are teaching. It may, at first, seem intimidating, so you could allocate just a single week or case study on a module in the first instance, and then increase from there if you wish.

Transferability to different contexts

There are clearly some modules or courses where this method would not be appropriate. Those that are heavily prescribed content wise, perhaps by a professional or government body, for instance, are likely not a good fit. However, beyond such restrictions, there are many opportunities for using this method.

This method was developed in the context of modules on human rights, politics, and international relations. However, it is likely to be of use in modules that use case studies to explore themes with broader applicability.

Beyond just feeding into the structure and focus of teaching and developing a shared stake in a module, this method can also help a teaching team get a feel for the interests of their students. Finally, adopting the language of democracy links in with pre-existing discourses that connect individuals to larger groups and society, and the benefits and responsibilities that arise from these connections.

Links to tools and resources

Albert Hirschman Centre (2021) What Keeps Democracy Alive? Interview with Till van Rahden. https://www.graduateinstitute.ch/communications/news/what-keeps-democracies-alive – This podcast contains insights into different ways of thinking about democracy, helping us broaden our conceptions beyond visits to the ballot box (as important as those are!).

Healey, M. (2015) Engaging Students As Partners and As Change Agents. Keynote Speech at University of Derby’s Learning and Teaching Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CyEPup5qbMU – Speech by a key UK advocate of think of students as partners.

The University Of Queensland Institute for Teaching and Learning Innovation (2021) Students as Partners. https://itali.uq.edu.au/advancing-teaching/initiatives/students-partners – This site has loads of great resources for thinking about how to bring students into decision making processes, as well links to relevant research.

References

Healey, M. Flint, A. Harrington, K. (2014). Engagement through partnership: students as partners in learning and teaching in higher education. Higher Education Academy. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/engagement-through-partnership-students-partners-learning-and-teaching-higher

Lubicz-Nawrocka, T. M. (2018). Students as partners in learning and teaching: the benefits of co-creation of the curriculum. International Journal For Students as Partners, 2(1), 47-63. https://doi.org/10.15173/ijsap.v2i1.3207

Matthews, K. E. (2016) Students as partners as the future of student engagement. Student Engagement in Higher Education, 1(1), 1-5.

Image Attribution

Election box vector created by macrovector from FreePik