MOOMobiPBL: Moodle Mobile Problem-Based Learning

Anuradha Peramunugamage

What is the idea?

The rapid advancement of technology has played a significant role in our day-to-day lives. The COVID19 pandemic had a profound effect on education, enabling us to learn remotely. Students today are accustomed to spending their days with smart devices due to the abrupt change in learning and teaching mechanisms. The majority of students in Sri Lanka used their mobile phones for educational and instructional purposes. As a result, we decided to promote active learning through the use of a mobile application called MOOMobiPBL. It is a proof-of-concept plugin for the Moodle platform. A plugin was developed and tested with undergraduate engineering students to promote Problem-Based Learning (PBL): by incorporating a learning problem into the course, the teacher creates an activity for learning. This concept has been tested in a blended or hybrid environment as well. The primary problem can be subdivided into sub problems, and students can work collaboratively to solve the problem. Each group of students is assigned the same learning problem and works in a discrete virtual workspace. Moodle mobile PBL supports a variety of self, peer, and teacher-administered assessment schemes. The teacher can create peer evaluation sheets for students to use to evaluate both their group members and themselves. Additionally, the plugin keeps track of each student’s activities and contributions.

Why this idea?

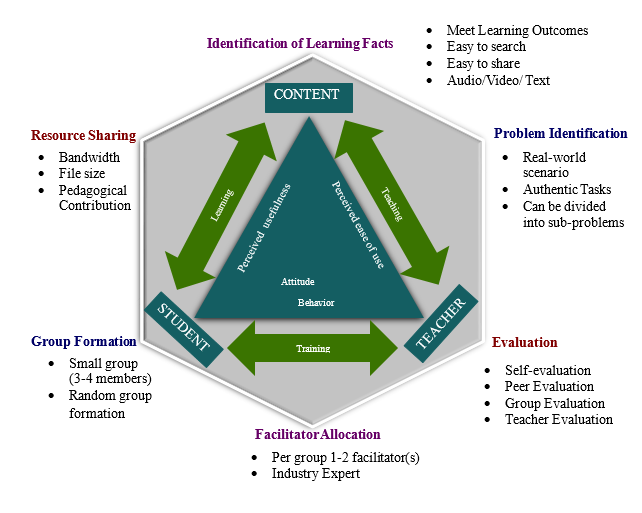

PBL provides opportunities for students to work as active learners. PBL requires more individual attention from the teachers as facilitators to guide the students in the right direction. Moodle allows teachers to share content and asynchronous communications. However, there are a set of drawbacks to implementing the PBL in Moodle environment. For instance, Moodle does not facilitate group peer evaluation. As a solution, a Moodle mobile plugin (MOOMobiPBL) was initially designed and developed to enhance PBL among engineering students. MOOMobiPBL supports teachers in the setup of their courses, encouraging a blended learning manner and students participating actively in the course activities. Figure 1 shows the developed theoretical framework (MobiPBL) that can be adopted in any kind of educational setting. To develop the framework Barrett’s (2006) PBL framework steps were considered. Additionally, the didactic triangle and Technology Adoption Model (TAM) were considered. In the MOOMobiPBL all evaluation methods were used i.e. self, peer, group, and teacher evaluations.

How could others implement this idea?

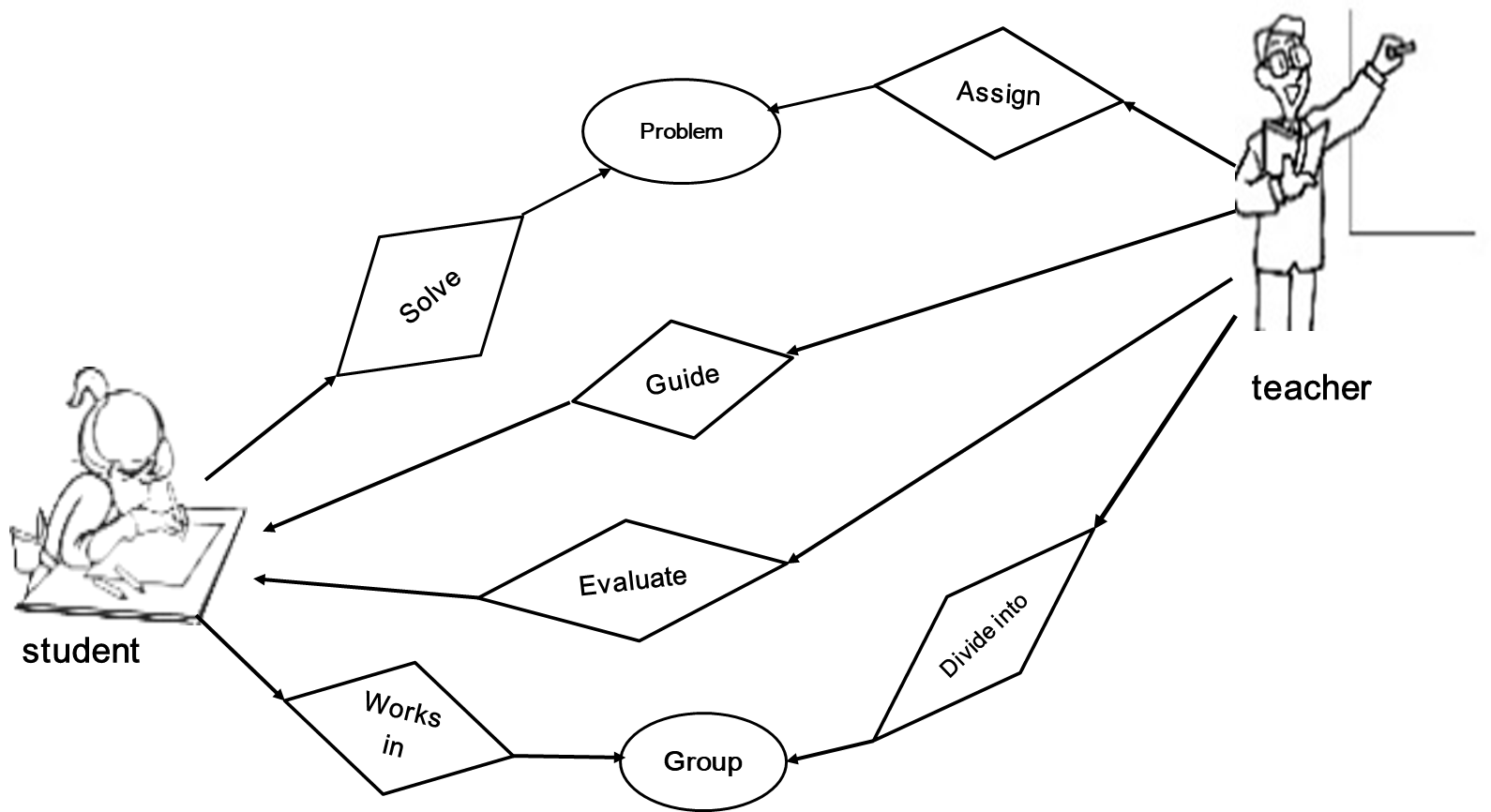

Problem-Based Learning is a student-centric teaching methodology that promotes “active, constructive, contextual, cooperative, and goal-directed learning” (Barrows et al., 1980). Implementation of the PBL differs from course to course based on the learning objectives of the module. However, teachers can follow similar steps to construct the activities as shown in figure 2. PBL has been implemented in many areas of health education, such as dentistry, pharmacy, and nursing, in universities worldwide (Kolmos & Holgaard, 2008; Mohd-Yusof et al., 2013). In the early ’90s, PBL was further applied in different disciplines such as architecture, law, and social work (Barrows et al., 1980). It was also applied in professional education fields like nursing, industrial design, optometry, architecture, law, and business (Chappell & Hager, 1995). However, online or mobile PBL implementation is in the primary stage.

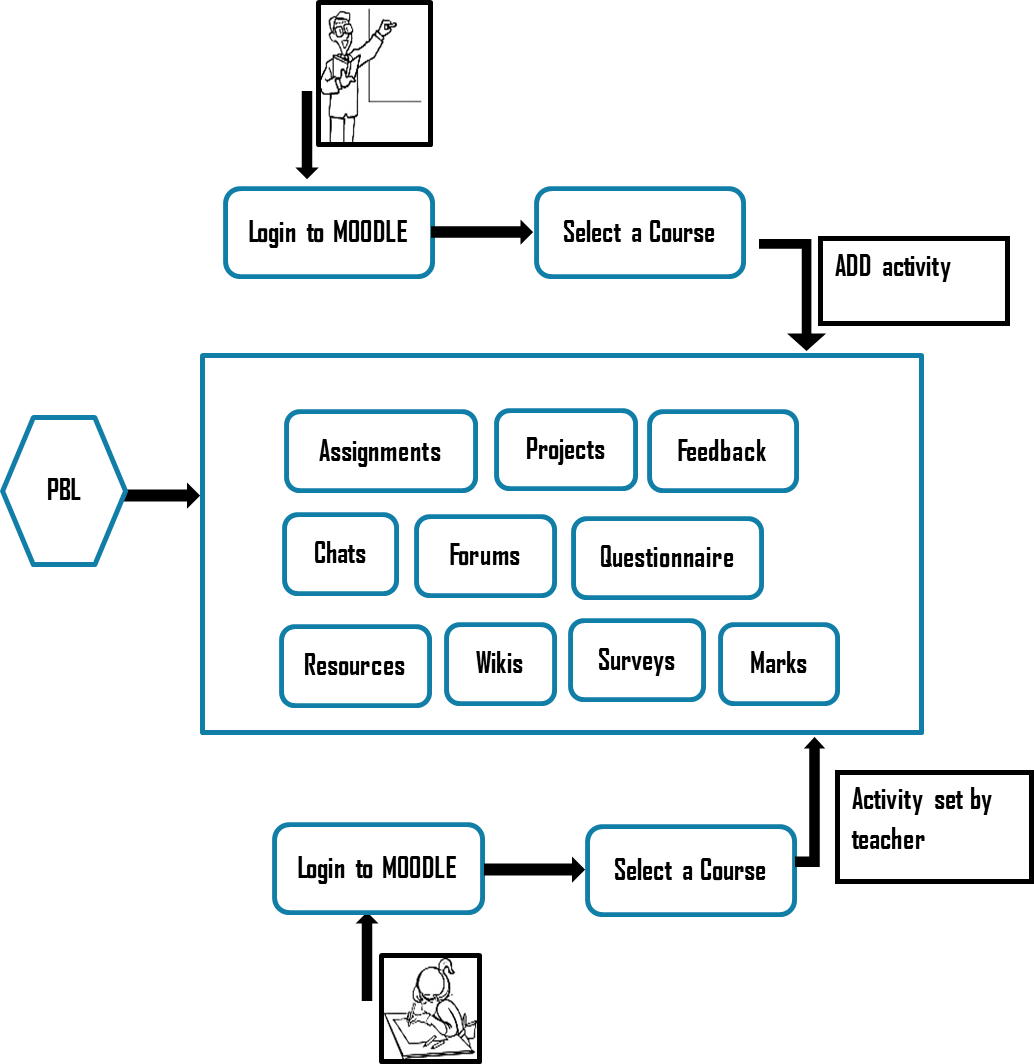

When developing PBL courses through the MOOMobiPBL environment, teachers can divide the activities. The large group size and the open-ended nature of online discussions did not allow for students to effectively collaborate. For large classes, a proper mechanism to engage with all participants must be devised, else some may drop out of the activities. Moreover, the nature of the course needs to be considered when introducing online activities, as set out in Figure 3.

Transferability to different contexts

MOOMobiPBL was first evaluated using engineering modules. However, if a teacher wishes to monitor individual interactions between a teacher and a student, between a teacher and a group of students, or between students, the plugin can be used, as it enables everyone to participate in active learning. Additionally, the plugin can be used to implement PBL at the course, module, or activity level. The plugin enables students to reflect on and track their progress through the course. Peer assessment, individual or group assignments, and teacher assessment via assignments and examinations all help students and teachers keep track of their progress. Generally, the steps below can be used to configure a course with Moodle-based PBL activities.

Step 1: Divide students into groups (random or based on preference)

Step 2: Assign the project to groups and allow students to subdivide it into smaller projects

Step 3: Submit individual reports for discussion within the group

Step 4: Keep track of each student’s contribution

Step 5: Before submitting the final project (report, presentation, or artifact) outcome, solicit feedback from the group and preview the final report

Step 6: Maintain a student diary in which all project-related details are recorded (Even if the student uploaded a report for the project). If a person is an evaluator, he or she will allow evaluation of the assigned projects/group activity

Step 7: Students may submit a summary contribution report for each project

Tools and resources

Peramunugamage, A., Usoof, H., & Hapuarachchi, J. (2019). Moodle Mobile Plugin for Problem-Based Learning (PBL) in engineering education. 2019 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON) (pp. 827-835). https://doi.org/10.1109/EDUCON.2019.8725062.

Peramunugamage, A., Usoof, H.A., Dias, W. P. S., & Halwatura, R. U. (2020). Problem-Based Learning (PBL) in engineering education in Sri Lanka: A Moodle based approach. In M. Auer, H. Hortsch & P. Sethakul (Eds.), The Impact of the 4th Industrial Revolution on Engineering Education (Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing book series, vol. 1134). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-40274-7_74

References

Barrett, T. (2006). Understanding problem-based learning. In T. Barrett, I. MacLabhrainn & H. Fallon (Eds.), Handbook of enquiry & problem based learning (pp. 13-25). CELT. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242683636_Understanding_problem-based_learning

Barrows, H. S., Robyn, M., & Tamblyn, M. (1980). Problem-Based Learning: An approach to medical education. Springer Publishing Company.

Chappell, C. S., & Hager, P. (1995). Problem-Based Learning and competency development. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.1995v20n1.1

Kolmos, A., & Holgaard, J. E. (2008). Learning styles of science and engineering students in problem and project-based education. Proceedings of 36th European Society for Engineering Education, SEFI Conference on Quality Assessment, Employability and Innovation. Aalborg, Denmark.

Mohd-Yusof, K., Arsat, D., Borhan, M. T. B., de Graaff, E., Kolmos, A., & Phang, F. A. (2013). PBL Across Cultures. Aalborg Universitetsforlag.

Image Attributions

Figure 1. Mobile learning (MobiPBL) framework by Anuradha Peramunugamage is used under CC-BY 4.0 licence

Figure 2. PBL workflows and functions by Anuradha Peramunugamage is used under CC-BY 4.0 licence

Figure 3. Moodle mobile PBL activities and steps by Anuradha Peramunugamage is used under CC-BY 4.0 licence