Object-based learning: active learning through enquiry

Dr Vicki Dale; Dr Nathalie Tasler; and Dr Lola Sánchez-Jáuregui

What is the idea?

Object-Based Learning (OBL) is a well-established teaching method; Korda (2020), for example, documents how objects were used in 19th century school teaching in Europe. However, it is only relatively recently that its potential has been recognised in UK higher education, popularised by the work of Chatterjee et al. (2011). It has been defined as ‘a mode of education which involves the active integration of objects into the learning environment’ (Chatterjee et al., 2016, p.1).

The University of Glasgow Hunterian Museum’s extensive collections lend themselves to enquiry-based learning across the disciplines. This gives us a unique opportunity to introduce OBL within our Postgraduate Certificate in Academic Practice (PGCAP), in our Creative Pedagogies for Active Learning course. In partnership with museum colleagues, this raises awareness of the potential for its use in learning and teaching in various degree subjects.

OBL supports active participation through aisthesis (Bleakley, 1999) and embodied learning (Chatterjee et al., 2016); the combining of the working with the head (cognitive dimension), the hands (psychomotor dimension), and the heart (affective dimension); thus, it is a powerful pedagogy for facilitating critical thinking and behaviour change.

This chapter defines OBL, and using examples from practice, illustrates how it may be used online and on campus, not only drawing upon specific collections, but also everyday objects that stimulate inquiry and active learning.

Why this idea?

We are surrounded by objects. With its origins in ethnography, material culture is the study of objects and how they came into being and are used culturally (Willocks, 2016). While this preempts us to think about museum artefacts, and the ethics of their collection, display and potentially repatriation, OBL can be extended to any physical object that exists, human-made or natural. Scientific equipment, specimens (animal, vegetable, or mineral), works of art, historic manuscripts, all come under this category. However, everyday household or personal objects can also lend themselves to learning; the use of such objects in art and design education for example has been shown to elicit a ‘wow’ response from students and facilitate analysis and critical reflection (Hardie, 2015). As well as subject knowledge, objects can facilitate transferable skills such as communication, team working, lateral thinking, and observational and drawing skills (Chatterjee, 2011).

How could others implement this idea?

While objects for learning can be sourced from everyday life, you may wish to liaise with colleagues in institutional museums or special collection libraries to source materials of a historical, art-based, or scientific nature. Colleagues in museums and libraries play a valuable role in identifying and using objects for learning, not just in higher education but also with the wider public, including schools. It can be helpful if a repository has an online database to describe and contextualise the object before seeking to get access physically.

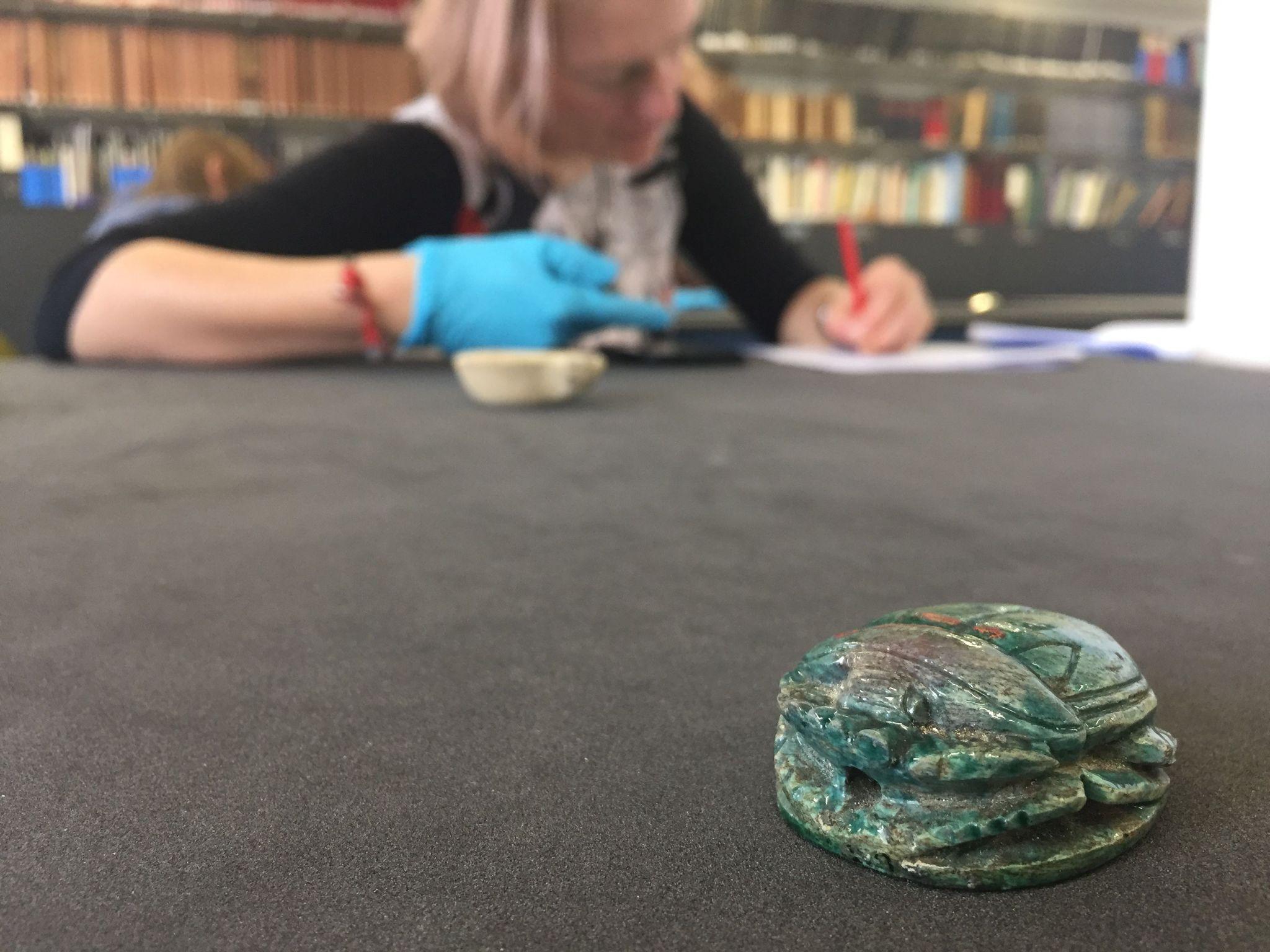

One particularly useful activity, to stimulate enquiry, is to ‘interview’ or ‘interrogate’ an object. At UofG, museum colleagues use a ‘ways of looking’ worksheet to really encourage learners to develop their powers of observation, and promote enquiry and curiosity. The worksheet is quite detailed; however, the salient prompts could be distilled as follows:

- Why did you choose this object; what does it mean to you personally?

- What does it look like? Describe its size, shape, colour, texture. Draw the object.

- Does it have an evocative smell? What happens when you handle the object and observe it from different viewpoints and distances?

- How was the object created? If human-made, when was it made, and why?

- Who produced and/or owned the object before it came into the collection?

- What can it tell you about the context from which it was derived, and the thinking and values of society at that time?

- What is the relevance of the object to how we think about knowledge and values in society today?

- Learners should be encouraged to take their time conducting this initial enquiry. Value can be added by encouraging learners to ‘present’ the results of their enquiry to others, and to negotiate meaning from different perspectives. Ultimately, the object is a mediating artefact for discussion and knowledge production.

Objects can also be used to support a more student-centred approach to enquiry. For example, students could work collaboratively to select, investigate and present objects. Such an approach would allow students to focus on different aspects of the enquiry, in terms of combining their investigative efforts.

Transferability to different contexts

While this guide suggests the use of OBL within a higher education context, academics may also wish to use objects in community outreach activities, perhaps with the general public or in the context of widening participation activities or summer schools. Objects are also multidisciplinary; the example illustrated below – 1700-1800 Queyu apron – could be examined from the perspective of textile and conservation, history, fashion, sociocultural anthropology, global history, material design, and would have its own object biography associating it historically with individual and communities.

Alternative objects in the Hunterian museum that would lend themselves to OBL include those from scientific, geological, archaeological, ethnographic, and art collections. One of the objects is an ongoing science experiment – Lord Kelvin’s artificial glacier from the 19th century!

Not all institutions or learners have access to curated objects; however, this is an opportunity to think creatively about pedagogical investigation of everyday objects. In our own PGCAP course, we make reference to how something as simple as a bag of sweets can stimulate conversations about diet, dental health, design, marketing, production, distribution, recycling, etc.

While physical objects have a particular attraction, in terms of their tangibility and authenticity evoking an emotional response, virtual collections have the benefit of being more widely accessible and many museums and collections are increasingly making digitised resources available, which can be particularly helpful in the current pandemic circumstances.

Links to tools and resources

- Monica Callaghan, former Head of Education at the Hunterian Museum Glasgow, discussing OBL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NCAsArlYO18

- Teaching and Object-Based Learning: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/culture/schools/teaching-object-based-learning

- Object-Based Learning Overview – Dr Andrew Jamieson talking about OBL at Monash University: https://vimeo.com/129634707

- The Hunterian Museum. Learning resources: Resources for home learning: https://www.gla.ac.uk/hunterian/learning/museumeducation/

- The Hunterian Museum: Collections highlights: https://www.gla.ac.uk/hunterian/collections/collectionshighlights/ [includes Kelvin’s pitch glacier experiment]

References

Bleakley, A. (1999). From reflective practice to holistic reflexivity. Studies in Higher Education, 24(3), 315-330. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079912331379925

Chatterjee, H. J. (2011). Object-based learning in higher education: The pedagogical power of museums. http://dx.doi.org/10.18452/86

Chatterjee, H. J., Hannan, L., & Thomson, L. (2016). An introduction to object-based learning and multisensory engagement. In Engaging the senses: Object-based learning in higher education (pp. 15-32). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315579641

Hardie, K. (2015). Wow: The power of objects in object-based learning and teaching (Innovative pedagogies series). Higher Education Academy. https://s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/assets.creode.advancehe-document-manager/documents/hea/private/kirsten_hardie_final_1568037367.pdf

Korda, A. (2020). Object lessons in Victorian education: Text, object, image. Journal of Victorian Culture, 25(2), 200-222. https://doi.org/10.1093/jvcult/vcz064

Willcocks, J. (2016). The power of concrete experience: Museum collections, touch and meaning making in art and design pedagogy. In Engaging the senses: Object-based learning in higher education (pp. 57-70). Routledge.

Image Attributions

Figure 1. A Victorian forged Egyptian scarab beetle in the foreground, during an object-based learning ‘ways of looking’ learning activity in the Hunterian Museum teaching collections, by Vicki Dale, is used under CC BY 4.0 license.

Figure 2. “Queyu Apron (GLAHM:E.193/1)” from The Hunterian, University of Glasgow, is used under CC BY 4.0 license.