Padlet poetry: student poetry and art reflections as critical legal learning

Dr Melanie Stockton-Brown

What is the idea?

Pedagogy within teaching has historically focused on knowledge retention, as opposed to reflecting emotionally on the content. Encouraging students to reflect on complex theories whatever the discipline addresses this pedagogical gap. This might be through creative expressions including poetry, songs, artwork, and creative writing.

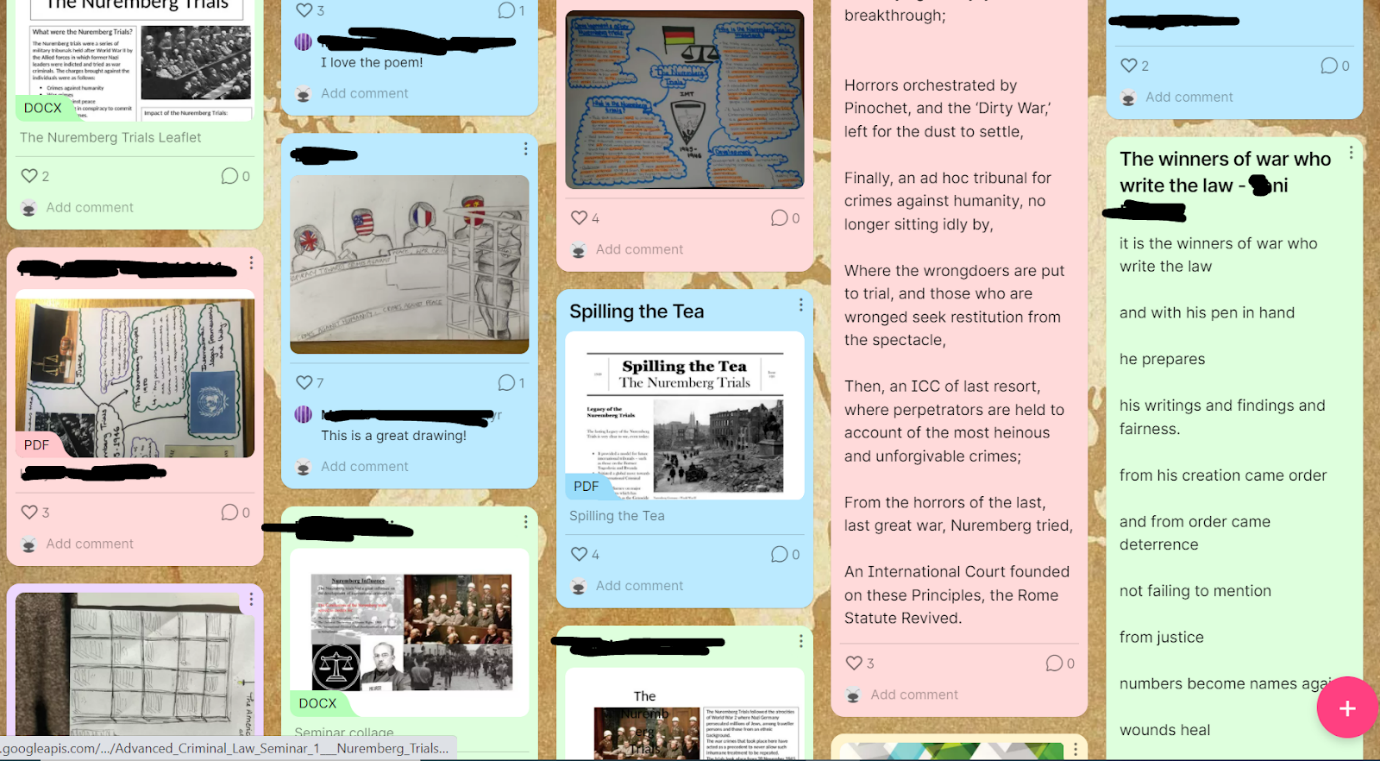

We trialled this teaching approach on a Law degree. Students each created a response in a medium of their choice to legal content delivered via lecture. Sharing these responses on Padlet created an archive, and allowed students to comment on each other’s work, building connections. Students who have been part of these online workshops fed back how enjoyable they found them, and how much deeper they now understand the content.

Why this idea?

Deep learning is achieved when students can understand the relationship between ideas, concepts and theories and bring them together as a whole, to understand the issue being examined (Fry et al., 2009). Therefore, the pedagogy behind this task was the concept of learning through action and experience, which combines action learning (learning through doing) and experiential learning (Skinner, 2010). Combined, this approach leads to active and deep learning, with learning situated in a social and legal context. Learners were encouraged to reflect on their own experiences, opinions, questions, and areas that interested them in the topic (the international criminal trials following World War 2), to then generate a creative response to the legal topics.

This approach is highly beneficial to facilitating active learning, as it cultivates self-directed learning, through approaching students as learning partners, and encouraging them to do the same. This idea is rooted in the concept that students can be scholars, change agents and teachers, and that the historical hierarchy of student and lecturer as distinct is not productive to learning (Healey et al, 2015).

Open conversation and critical discussion flowed in the session with much more ease in comparison to other teaching sessions, and engaged students who often remain silent. In creating their individual responses, the students were actively and consciously engaging with the content, as well as actively reflecting on what they have learned, and the commentary they have engaged with. Students could then reflect on the creative responses others had created, looking for the views they shared, and views that they challenged.

How could others implement this idea?

The session utilised a Padlet board, which can be set up for free. It is a great resource for granting access to students, as sharing the URL link will allow them to access the board and interact with it.

There are a number of different templates that can be used, including a timeline template and a template in which users can comment on a central image, as well as a board similar to a notice board.

The board allows students to upload content (such as images, music, text, hyperlinks, etc.), as well as to comment on the posts of others. You can choose to allow students to post anonymously, or you can disable that. I disabled the name function in the session, to increase their confidence in posting comments, which seemed to work well.

Clear instruction prior to the session was key, and I ensured the students had at least one week to make their creative responses and upload them. I also included links to sources for inspiration, including a variety of content to appeal to the diverse range of students.

Crucially, providing a starting-point or first creative work for the students will increase their confidence level to also share their responses. For that reason, I created my own response to the criminal trials, which was a poem accompanied by a visual collage, and uploaded that as I made the Padlet board visible to the students.

I also encouraged them to comment on each other’s content as it was uploaded, and made sure I commented on each student’s upload. This meant by the time we had the live session together, the students had seen each other’s work and were keen to discuss it in more depth.

Have a list of 2 or 3 questions or prompts ready to guide the students, if they are not actively engaging at first.

Once the session is finished, share the URL in the VLE or via email with the students, so they can continue to access the resources (especially for revision). The content can be downloaded as a PDF, which is formatted well for sharing with students.

Transferability to different contexts

This session could be utilised in any subject area, with both larger and smaller groups of students. It could enhance the pedagogical tools of law lecturers but is adaptable to any content. The emphasis on transferring this approach to alternative content is context, and ensuring students are reminded of the importance of sensitivity to certain themes, and to the fact that their fellow students may have personal experience of these sensitive topics.

Similar tasks that can be considered are discussed in Chapters 5d (on haikus for learning) and in Chapter 6d (student-generated podcasts). These tasks encourage creativity and active learning through doing.

Links to tools and resources

Padlet: https://en-gb.padlet.com/

References

Fry, H., Ketteridge, S. and Marshall, S., 2009. A handbook for teaching and learning in higher education: Enhancing academic practice (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Healey, M., Bovill, C., & Jenkins, A. (2015). Students as partners in learning. In J. Lea (Ed.) Enhancing Learning and Teaching in Higher Education: Engaging with the Dimensions of Practice (pp. 141-172). Oxford University Press.

Skinner, D. (2010.) Effective Teaching and Learning in Practice. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Image Attributions

Figure 1. Collage by Melanie Stockton-Brown is used under CC-BY 4.0 Licence

Figure 2. Student Poems Padlet Screenshot by Melanie Stockton-Brown is used under CC-BY 4.0 Licence