Using multimedia to teach critical and contextual studies

Dr Artemis Alexiou

What is the idea?

Critical and Contextual Studies (CCS) modules offer students the opportunity to learn about their discipline’s historical and contemporary practice, so they are able to position their own practice within this context. Typically, students learn about historical and contemporary concepts and practices when reading academic texts written by specialist authors in the field. This approach to knowledge has its own benefits, yet, this chapter suggests an alternative method of delivery for this type of information: a learning activity using pre-recorded presentations by key speakers.

Rationale for idea

In the 1970s, the Coldstream reports argued for changes in higher education that would “improve the status of artists and designers” (Borg, 2012, p. 4); namely the implementation of Contextual and Critical Studies (CCS) modules to all art and design HE courses. Since then, art and design education at university level has been “almost uniquely divided against itself” (Frayling, 2004, p. 40), often because CCS is taught in a traditional manner that tends to “reinforce students’ roles as passive learners” (Ebert-May et al., 1997, p. 601). Subsequently, the requirements of academic study, which are quite different from those of experiential learning study, create an indisputable anxiety to art and design students, including many dyslexic students and students with other mental or learning difficulties typically included in this cohort.

Research reveals that teaching CCS is most effective when instructors follow an active learning approach, which has been found to improve academic achievement and encourage an inclusive environment for all students (Baepler & Walker, 2014; Bamber & Tett, 2001; Haggis & Pouget, 2002; Parker et al., 2005; Smith & Cardaciotto, 2011; Thomas, 2002; Weller, 2016). Furthermore, an active learning approach can be applicable and beneficial for small-size and large-size classes, when planned appropriately, whilst alternative forms of delivering content help students learn effectively (Berk, 2009; Falchikov, 1995; Stefani, 1994).

Step-by-step instructions on how to implement

Step 1: Identify the learning outcomes of your teaching episode, within the context of your module

Think about the learning outcomes of your module, asking: where does this teaching episode stand within this context? Once you are able to identify exactly what is the content that you wish to deliver during this teaching episode, you will then be in a position to write down the learning outcomes of this specific session.

Step 2: Understand your student cohort

Think about your student group. Are they experienced thinkers and writers, or not? In which stage of their studies are they in? Does your student group have a mixture of confident and timid students? Is your student group mono-disciplinary or multidisciplinary? Do students have similar skills in critical thinking? Does your student group have a mixture of team-workers and loners? Do students tend to consistently sit with their friends? Does the student group have any students with learning difficulties or ESOL students?

Step 3: Identify an appropriate learning method

Following the in-depth study of your student group described above, you can now identify the most appropriate teaching and learning method for this specific group of students. This chapter argues that an active and humanist learning approach (Weller, 2016; Rogers, 1961) would be most helpful in the majority of cases.

Step 4: Identify a suitable learning activity

Taking into consideration the learning outcomes of this specific teaching episode (Step 1), the specific characteristics of this student group (Step 2), and the specific learning method you wish to implement (Step 3), you now have to decide what learning activity would be most suitable. Then, having decided the type of activity you wish to organise, you have to look for appropriate resources.

More specifically, let’s assume you are planning a teaching episode that aims to communicate the difference between art and design practice to a multi-disciplinary group of design students. The group includes Level 4 students of diverse strength and from diverse backgrounds. Yet, most students have one common characteristic: they generally refrain from reading academic texts and have a short attention span. With that in mind, a learning activity that incorporates non-textual content and collaboration amongst peers may prove beneficial. For instance, you can use a recording from an international event showing an established design historian discussing the difference between art and design, asking students to identify key information from this presentation.

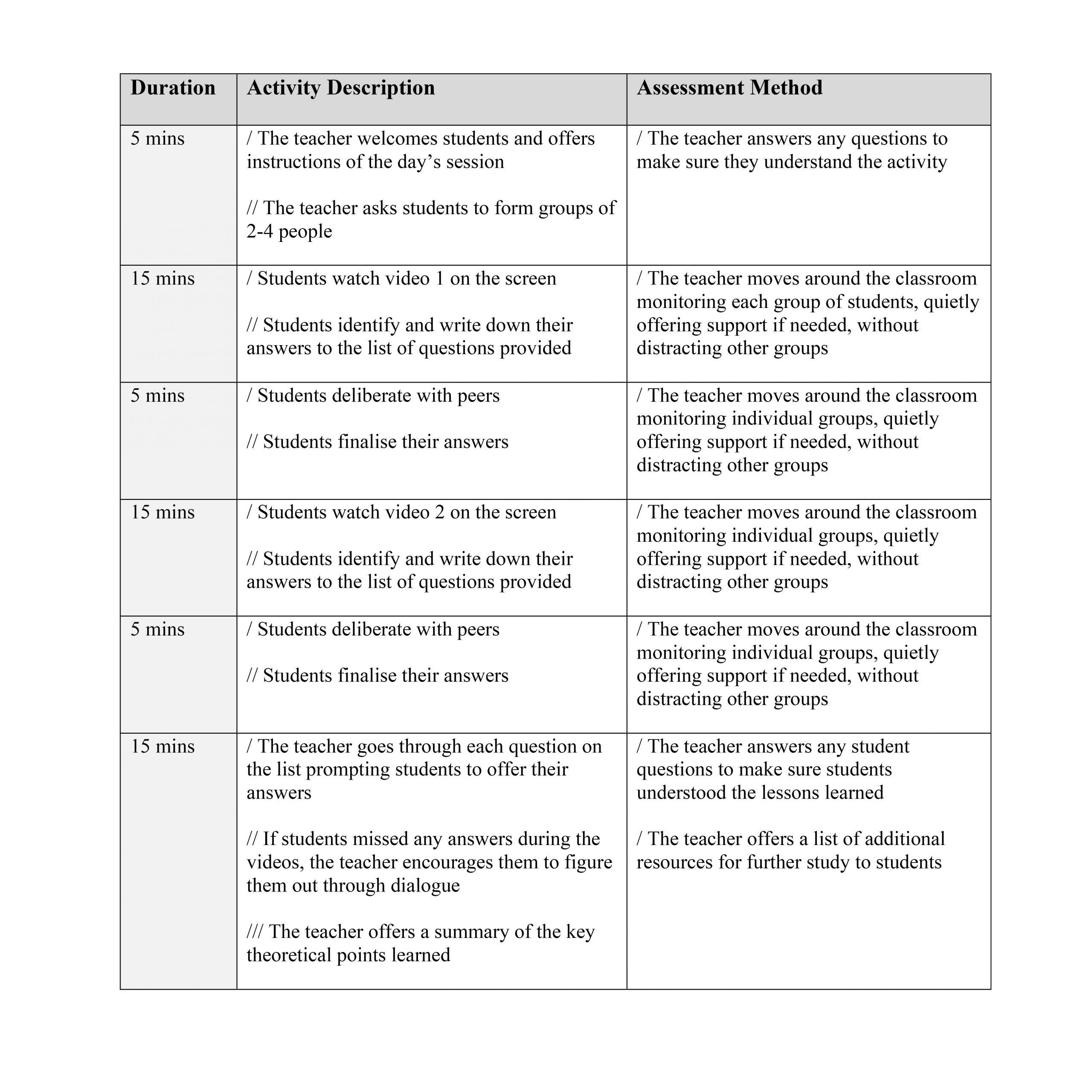

Step 5: Plan the teaching session minute by minute, from start to finish

Having completed the above steps, you are now in a position to plan your teaching episode minute by minute. Remember, to include all the parts of the hourly session, such as welcome, instructions, breaks etc. and consider how you will assess your aim was achieved.

To continue with the above example, your teaching plan may include:

Step 6: Identify the facilities and resources required

Finally, you have to plan ahead in terms of the facilities and resources required to deliver your teaching episode. Have you found a suitable space large enough to fit your student group? Does the classroom have the appropriate furniture in place for your learning activity? Does the classroom have the appropriate IT facilities? Can all students see and hear clearly the video on the screen? Do you need to print hand-outs in advance? Do you need to bring other supplies with you, such as pens?

Transferability to different contexts

This learning activity can be applied to small-size and large-size student cohorts, and is especially suitable for learner groups studying practice-based subjects (art, design, nursing, social work etc.).

References

Baepler, P., & Walker, J. D. (2014). Active learning classrooms and educational alliances: Changing relationships to improve learning. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 137, 27-40. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.20083

Bamber, J., & Tett, I. (2001). Ensuring integrative learning experiences for non-traditional students in higher education. Journal of Widening Participation and Lifelong Learning, 3(1), 8-16.

Berk, R. A. (2009). Multimedia teaching with video clips: TV, movies, YouTube, and mtvU in the college classroom. International Journal of Technology in Teaching and Learning, 5(1), 1-21.

Borg, E. (2012). Writing differently in art and design: Innovative approaches to writing tasks. In C. Hardy & L. Clughen (Eds.), Writing in the disciplines building supportive cultures for student writing in UK Higher Education. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://pureportal.coventry.ac.uk/en/publications/writing-differently-in-art-and-design-innovative-approaches-to-wr-2

Ebert-May, D., Brewer, C., & Allred, S. (1997). Innovation in large lectures: Teaching for active learning. BioScience, 47(9), 601–607. https://doi.org/10.2307/1313166

Falchikov, N. (1995). Peer feedback marking: Developing peer-assessment. Innovations In Education and Training International, 32(2), 175-187. https://doi.org/10.1080/1355800950320212

Frayling, C. (2004). To art and through art. In P. Bonaventura, & S. Farthing (Eds.), A Curriculum for Artists (pp. 38-41). The University of Oxford.

Haggis, T., & Pouget, M. (2002). Trying to be motivated: Perspectives on learning from younger students accessing higher education. Teaching in Higher Education, 7(3), 323–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510220144798a

Parker, S., Naylor, P., & Wannington, P. (2005). Widening participation in higher education: What can we learn from the ideologies and practices of committed practitioners?. Journal of Access Policy and Practice, 2(2), 140-160.

Rogers, C. R. (1961). On becoming a person: A therapist’s view on psychotherapy. Houghton Mifflin Company.

Smith, C. V., & Cardaciotto, L. (2011). Is active learning like broccoli? Student perceptions of active learning in large lecture classes. Journal of Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 11(1), 53-61.

Stefani, L. A. J. (1994) Peer, self and tutor assessment: Relative reliabilities. Studies in Higher Education, 19(1), 69-75. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079412331382153

Thomas, L. (2002). Student retention in higher education: The role of institutional habitus. Journal of Education Policy, 17(4), 423-442. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930210140257

Weller, S. (2016). Academic practice: Developing as a professional in higher education. SAGE.