Using online comic strip generators to enhance the student experience in bioscience education

Dr Shelini Surendran and Geyan Sasha Surendran

What is the idea?

The use of sequential illustrations to tell stories has been present since prehistoric humans painted series of pictures on caves to effectively transmit culture and values to their children (Hadzigeorgiou & Stefanich, 2000). In education, storytelling is a useful approach for learning, allowing kinaesthetic learners to remember the emotional connections associated with the story, reinforcing context-based learning (Hadzigeorgiou & Stefanich, 2000). Comic strips are examples of multimodal texts that combine both text and imagery for storytelling (Wijaya et al., 2021). Comics have the ability to concisely convey immediate visceral meanings that textbooks cannot.

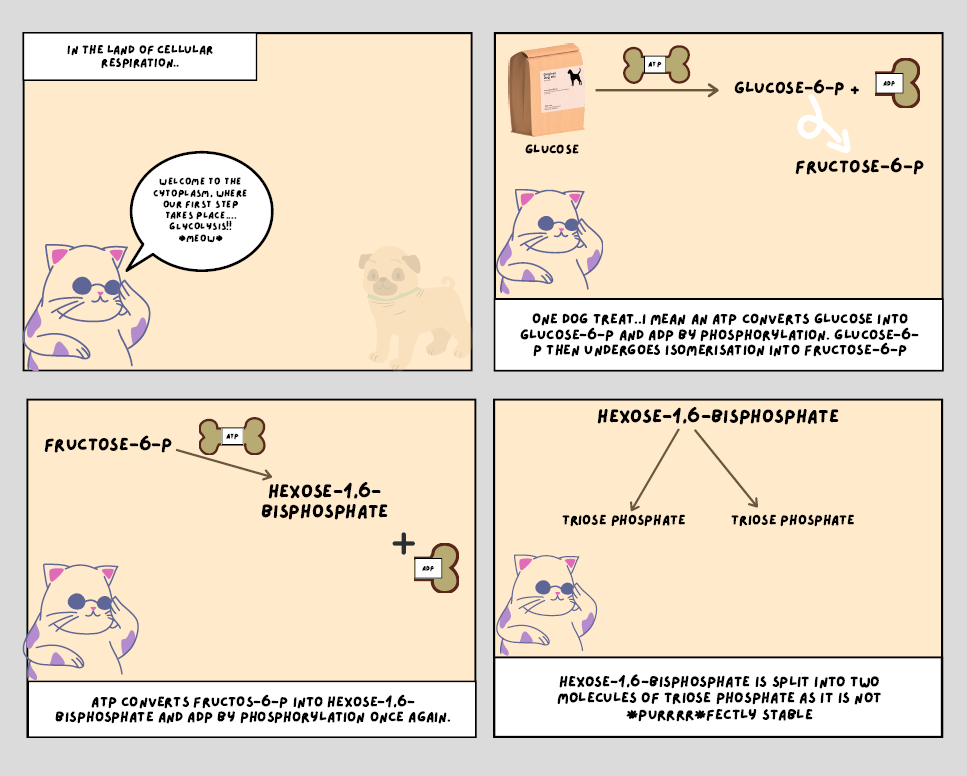

Students were encouraged to use speech bubbles and technical words related to the stages of cellular respiration within their storyline. Finally, students were told to write their comic strips in a creative way, for example the students could portray mitochondrion as a superhero such as ‘Energy-cat’ or any other fun character. The role of the teacher was to facilitate the creation of the stages of respiration. At the end of the activity, students were formatively assessed using a marking criteria (Table 1).

Why this idea?

Comic strips have been used in the humanities and have been largely ignored in science education. For a long time, comic strips had been deemed as only suitable for children, as they do not contain lengthy prose. However, comic strips have the power to convey important scientific messages in a more interesting and comprehensible way for adults, compared to using a textbook or newspaper articles (Koutnikova, 2017). Comic strips are memorable learning aids, as they are usually organised in panels containing a single message (González-Espada, 2003; McCloud 1993).

Comic strip reading is an active process as the reader needs to fill the gaps between the juxtaposed panels, which contain a complex interplay of words and images (Rota & Izquierdo, 2003). Moreover, comic strips encompass elements of humour and fun, which may make it a useful pedagogic tool to engage students and motivate them to read scientific content in a fun way (Garner, 2006). We observed from this activity that using educational comics makes learning fun and memorable. Comic strips are able to integrate cognitive processes associated with the psychomotor domain, due to the incorporation of auditory, kinaesthetic and visual learning methods (Wright & Sherman, 1999). Similar findings have been established that scientific comics enhance student interest and satisfaction in comparison to text-only books (Lin et al., 2015). One of the main advantages of implementing comic strips was that no previous artistic skills were required when using online comic strip generators. There was an obvious observed enhancement of the creative thinking, personal expression and communicative skills of our students (Lazarinis et al., 2015). Classroom management within this activity was minimal and many students were driven by its fun nature and worked outside classroom hours voluntarily.

Student feedback:

‘By presenting respiration as a story, it made [learning about] cellular respiration less intimidating.’ – Student A

‘I used to hate reading text-books saturated with text and barely any pictures. This comic book activity made me realise that I am more eager to read when presented with images and an interesting story line and made me really understand cellular respiration properly.’ – Student B

‘Comic strips are so fun, and add a twist of humour to the class. It’s always the funniest moments and fun activities in life I remember, as opposed to the dull moments.’ – Student C

‘We enjoyed thinking about the process in a more creative way and thought that it was more interactive than a lecture. As we had creative freedom we could have a lot more fun with the concepts involved and found that it made us remember the topic a lot more. We also found that the experience felt a lot more relaxed than the usually assigned university work.’ – Student D

How can others implement this idea?

- Students can create a comic strip for revising a subject area they have been taught in class. Alternatively, a comic strip can be created as a flipped learning method (Students view online lectures prior to the classroom activity, then spend time in class engaging in active learning).

- Students can create a narrative storyline containing illustrations, individually or in small groups. You may choose to divide the class into small groups if the topic area is large. Using comic strips as a group activity, allows some students to have different team roles e.g. Idea generation, story writing and graphic designing. Students may also be given a list of essential keywords relating to their chosen topic as guidance.

- Creating a comic strip is no different to planning a story. Students should plan their comic strip, so it contains a beginning, middle and end. Students should think about the types of characters and scenes they plan to use, to portray what happened in the story. It’s important that the comic strip has a powerful ending and is packed with some action. It is recommended that students contain at least 20 panels within their comic strip, but this may vary depending on the complexity of the topic they plan to write about.

- Students can be recommended to use comic strip generators such as ‘Canva’ or ‘Pixton’. Students can start with a blank page or use pre-existing templates provided by the generator. Most comic strip generators have different themes (e.g. school, beach, city) and allow for customizable layouts (Number and type of comic strip panels). When it comes to designing, students can experiment with the different features available. Online comic strip generators often allow the addition of dialogue boxes, speech bubbles, custom artwork, colour schemes, typefaces, icons & stickers, customisable characters and illustrations. Tools like Canva allow for real time collaborative work, where multiple students can work on the same document at the same time online or in the classroom.

- Students’ comic strips must contain illustrations containing dialogue, they may use speech bubbles or dialogue boxes provided in the comic strips. The size of the font can indicate whether characters are shouting or whispering, for example capitalised text indicates that a character is shouting. It is important that students double check their spelling and grammar.

- Students must be as creative as possible and write their story in a comic-strip way. They could describe a scenario including a superhero, a teacher, or any fun character they can think of (See figure 1 as an example).

Transferability to different contexts

This comic strip activity can be adapted for any subject discipline. Creation of comic strips can be helpful for icebreaker activities, revision and consolidating knowledge. We would suggest readers to:

· Have a clear marking scheme on what you’re expecting from the comic strip. If you want to use this as a marked assignment, be clear on how many marks are awarded for the following: Theme, illustrated scenes, character & dialogue, spelling, grammar & punctuation; and creativity. (Table 1).

Practise making your own comic strips, so you can help students if needed.

Table 1.

|

Criterion |

Description |

Score |

|

Theme |

All panels relate to the theme of Cellular respiration. |

_/5 |

|

Illustrated scenes |

Each panel of the comic strip contains appropriate landscape, characters/ props and detailed illustrations that help strengthen understanding of the scene. The comic strip is clear and easy to understand.

|

_/5 |

|

Character & Dialogue |

The main characters of the comic strip are clear to the reader, and their dialogue helps with setting the scene. The comic strip may include speech bubbles or labels, containing all the necessary vocabulary words related to cellular respiration.

|

_/5 |

|

Spelling, grammar & punctuation |

Spelling, grammar and punctuation are correct throughout. |

_/5 |

|

Creativity |

The comic strip doesn’t simply regurgitate dry facts. Students exhibit creativity, and may include fun or humour or a novel way of explaining concepts within their pictures and captions.

|

_/5 |

|

Total |

|

_/25 |

Links to tools and resources

Useful resources for comic strip generation:

Useful website links to learn more about online comic strip generators:

References

Garner, R. L. (2006). Humor in pedagogy: How ha-ha can lead to aha!. College Teaching, 54(1), 177-180. https://doi.org/10.3200/CTCH.54.1.177-180

Gonzalez-Espada, W. J. (2003). Integrating physical science and the graphic arts with scientifically accurate comic strips: Rationale, description, and implementation. Revista Electrónica de Enseñanza de las Ciencias, 2(1), 58-66.

Hadzigeorgiou, Y., & Stefanich, G. (2000). Imagination in science education. Contemporary Education, 71(4), 23.

Koutníková, M. (2017). The application of comics in science education. Acta Educationis Generalis, 7(3), 88-98. https://doi.org/10.1515/atd-2017-0026

Lazarinis, F., Mazaraki, A., Verykios, V. S., & Panagiotakopoulos, C. (2015, July). E-comics in teaching: Evaluating and using comic strip creator tools for educational purposes. 10th International Conference on Computer Science & Education (ICCSE) (pp. 305-309). IEEE.

Lin, S. F., Lin, H. S., Lee, L., & Yore, L. D. (2015). Are science comics a good medium for science communication? The case for public learning of nanotechnology. International Journal of Science Education (Part B), 5(3), 276-294. https://doi.org/10.1080/21548455.2014.941040

McCloud, S. (1993). Understanding comics: The invisible art. Kitchen Sink Press.

Rota, G., & Izquierdo, J. (2003). “Comics” as a tool for teaching biotechnology in primary schools. Electronic Journal of Biotechnology, 6(2), 85-89. https://doi.org/10.2225/vol6-issue2-fulltext-10

Wijaya, E. A., Suwastini, N. K. A., Adnyani, N. L. P. S., & Adnyani, K. E. K. (2021). Comic strips for language teaching: The benefits and challenges according to recent research. ETERNAL (English, Teaching, Learning, and Research Journal), 7(1), 230-248. https://doi.org/10.24252/Eternal.V71.2021.A16

Wright, G., & Sherman, R. (1999). Let’s create a comic strip. Reading Improvement, 36(2), 66.

Image Attribution

Figure 1. Example of a comic strip created by a student using Canva by Daria Danielewicz and Emil Nikadon is used under CC-BY 4.0 Licence